Woodward effect

The Woodward effect, also referred to as a Mach effect, one of at least three predicted Mach effects, is part of a hypothesis proposed by James F. Woodward in 1990.[1] The hypothesis states that transient mass fluctuations arise in any object that absorbs internal energy while undergoing a proper acceleration. Harnessing this effect could generate a reactionless thrust, which Woodward and others claim to measure in various experiments.[2][3] If proven to exist, the Woodward effect could be used in the design of spacecraft engines of a field propulsion engine that would not have to expel matter to accelerate. Such an engine, called a Mach effect thruster (MET), would be a breakthrough in space travel.[4][5] So far, no conclusive proof of the existence of this effect has been presented.[6] Experiments to confirm and utilize this effect by Woodward and others continue.[7] The anomalous thrust detected in some RF resonant cavity thruster (EmDrive/Cannae drive) experiments may be explained by the same type of Mach effect proposed by Woodward.[8][9]

Mach effects

According to Woodward, at least three Mach effects are theoretically possible: vectored impulse thrust, open curvature of spacetime, and closed curvature of spacetime.[10]

The first effect, the Woodward effect, is the minimal energy effect of the hypothesis. The Woodward effect is focused primarily on proving the hypothesis and providing the basis of a Mach effect impulse thruster. In the first of three general Mach effects for propulsion or transport, the Woodward effect is an impulse effect usable for in-orbit satellite stationkeeping, spacecraft reaction control systems, or at best, thrust within the solar system. The second and third effects are open and closed spacetime effects. Open curved spacetime effects can be applied in a field generation system to produce warp fields. Closed-curve spacetime effects would be part of a field generation system to generate wormholes.

The third Mach effect is a closed-curve spacetime effect or closed timelike curve called a benign wormhole. Closed-curve space is generally known as a wormhole or black hole. Prompted by Carl Sagan for the scientific basis of wormhole transport in the movie Contact, Kip Thorne[11] developed the theory of benign wormholes. The generation, stability, and traffic control of transport through a benign wormhole is only theoretical at present. One difficulty is the requirement for energy levels approximating a "Jupiter size mass".

Hypothesis

Gravity origin of inertia

The Woodward effect is based on the relativistic effects theoretically derived from Mach's principle on inertia within general relativity and is attributed by Albert Einstein to Ernst Mach.[12] Mach's Principle is generally defined as "the local inertia frame is completely determined by the dynamic fields in the Universe."[13]

A formulation of Mach's principle was first proposed as a vector theory of gravity, modeled on Maxwell's formalism for electrodynamics, by Dennis Sciama in 1953,[14] who then reformulated it in a tensor formalism equivalent to general relativity in 1964.[15]

Sciama stated that instantaneous inertial forces in all accelerating objects are produced by a primordial gravity-based inertial radiative field (now referred as "G/I field" or "gravinertial field") created by distant cosmic matter and propagating both forwards and backwards in time at light speed. As previously formulated by Sciama, Woodward suggests that Wheeler–Feynman absorber theory would be the correct way to understand the action of instantaneous inertial forces in Machian terms.[16][17][18]

Sciama's inertial-induction idea has been shown to be correct in Einstein's general relativity for any Friedmann–Robertson–Walker cosmology.[19][20] According to Woodward, the Mach effects' derivation is relativistically invariant, so the conservation laws are satisfied, and no "new physics" is involved besides general relativity.[21]

Transient mass fluctuation

The following has been detailed by Woodward in various peer-reviewed papers throughout the last twenty years.[22][23][24]

According to Woodward, a transient mass fluctuation arises in an object when it absorbs "internal" energy as it is accelerated. Several devices could be built to store internal energy during accelerations. A measurable effect needs to be driven at a high frequency, so macroscopic mechanical systems are out of question since the rate at which their internal energy could be modified is too limited. The only systems that could run at a high frequency are electromagnetic energy storage devices. For fast transient effects, batteries are ruled out. A magnetic energy storage device like an inductor using a high-permeability core material to transfer the magnetic energy could be especially built. But capacitors are preferable to inductors because compact devices storing energy at a very high energy density without electrical breakdown are readily available. Shielding electrical interferences are easier than shielding magnetic ones. Ferroelectric materials can be used to make high-frequency electro-mechanical actuators, and they are themselves capacitors so they can be used for both energy storage and acceleration. Finally, capacitors are cheap and available in various configurations. So Mach effect experiments have always relied on capacitors so far.

When the dielectric of a capacitor is submitted to a varying electric power (charge or discharge), Woodward's hypothesis predicts[24] a transient mass fluctuation arises according to the transient mass equation (TME):

where:

- is the proper mass of the dielectric,

- is the gravitational constant,

- is the speed of light in vacuum,

- is the proper density of the dielectric,

- is the volume of the dielectric,

- is the instantaneous power delivered to the system.

This equation is not the full Woodward equation as seen in the book. There is a third term, , which Woodward discounts because his gauge sets ; the derivatives of this quantity must therefore be negligible.[24]

Propellantless propulsion

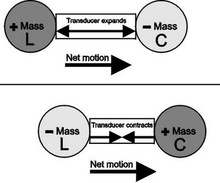

The previous equation shows that when the dielectric material of a capacitor is cyclically charged then discharged while being accelerated, its mass density fluctuates, by around plus or minus its rest mass value. Therefore, a device can be made to oscillate either in a linear or orbital path, such that its mass density is higher while the mass is moving forward, and lower while moving backward, thus creating an acceleration of the device in the forward direction, i.e. a thrust. This effect, used repeatedly, does not expel any particle and thus would represent a type of apparent propellantless propulsion, which seems to be in contradiction with Newton's third law of motion. However, Woodward states there is no violation of momentum conservation in Mach effects:[22]

| “ | If we produce a fluctuating mass in an object, we can, at least in principle, use it to produce a stationary force on the object, thereby producing a propulsive force thereon without having to expel propellant from the object. We simply push on the object when it is more massive, and pull back when it is less massive. The reaction forces during the two parts of the cycle will not be the same due to the mass fluctuation, so a time-averaged net force will be produced. This may seem to be a violation of momentum conservation. But the Lorentz invariance of the theory guarantees that no conservation law is broken. Local momentum conservation is preserved by the flux of momentum in the gravity field that is chiefly exchanged with the distant matter in the universe. | ” |

Two terms are important for propulsion on the right-hand side of the previous equation:

- The first, linear term is called the "impulse engine" term because it expresses mass fluctuation depending on the derivative of the power, and scales linearly with the frequency. Past and current experiments about Mach effect thrusters are designed to demonstrate thrust and the control of one type of Mach effect.

- The second, quadratic term is what Woodward calls the "wormhole" term, because it is always negative. Although this term appears to be many orders of magnitude weaker than the first term, which makes it usually negligible, theoretically, the second term's effect could become huge in some circumstances. The second term, the wormhole term, is indeed driven by the first impulse engine term, which fluctuates mass by around plus or minus the rest mass value. When fluctuations reach a very high amplitude and mass density is driven very close to zero, the equation shows that mass should achieve very large negative values very quickly, with a strong non-linear behavior. In this regard, the Woodward effect could generate exotic matter, although this still remains very speculative due to the lack of any available experiment that would highlight such an effect.

Applications of propellantless propulsion include straight-line thruster or impulse engine, open curved fields for starship warp drives, and even the possibility of closed curved fields such as traversable benign wormholes. [25]

Space travel

Current spacecraft achieve a change in velocity by the expulsion of propellant, the extraction of momentum from stellar radiation pressure or the stellar wind or the utilisation of a gravity assist ("slingshot") from a planet or moon. These methods are limiting in that rocket propellants have to be accelerated as well and are eventually depleted, and the stellar wind or the gravitational fields of planets can only be utilized locally in the Solar System. In interstellar space and bereft of the above resources, different forms of propulsion are needed to propel a spacecraft, and they are referred to as advanced or exotic.[26][27]

Impulse engine

If the Woodward effect is confirmed and if an engine can be designed to use applied Mach effects, then a spacecraft may be possible that could maintain a steady acceleration into and through interstellar space without the need to carry along propellants. Woodward presented a paper about the concept at the NASA Breakthrough Propulsion Physics Program Workshop conference in 1997,[28][29] and continued to publish on this subject thereafter.[30][31][32][33]

Even ignoring for the moment the impact on interstellar travel, future spacecraft driven by impulse engines based on Mach effects would represent an astounding breakthrough in terms of interplanetary spaceflight alone, enabling the rapid colonization of the entire solar system. Travel times being limited only by the specific power of the available power supplies and the acceleration human physiology can endure, they would allow crews to reach any moon or planet in our solar system in less than three weeks. For example, a typical one-way trip at an acceleration of 1 g from the Earth to the Moon would last only about 4 hours; to Mars, 2 to 5 days; to the asteroid belt, 5 to 6 days; and to Jupiter, 6 to 7 days.[34]

Warp drives and wormholes

As shown by the transient mass fluctuation equation above, exotic matter could be theoretically created. A large quantity of negative energy density would be the key element needed to create warp drives[35] as well as traversable wormholes.[36] As such, if proven to be scientifically valid, practically feasible and scaling as predicted by the hypothesis, the Woodward effect could not only be used for interplanetary travel, but also for apparent faster-than-light interstellar travel:

- The negative mass could be used to warp spacetime around a spaceship according to an Alcubierre metric.[23][35]

- Enough exotic matter could also be concentrated into a point of space to create a wormhole, and prevent it from collapsing. Woodward and others also state that exotic matter could defocus energy at the outer mouth of the wormhole (making it a white hole) and shape the throat of such a gravitational singularity flat enough to avoid horizon and tidal stresses, resulting in an "absurdly benign traversable wormhole" linking two regions of distant spacetime, a concept well spread in science fiction as stargates, which could be used for instant intergalactic travel or time travel.[10][23][36][37][38]

Patents and practical devices

Two patents have been issued to Woodward and associates based on how the Woodward effect might be used in practical devices for producing thrust:

- In 1994, the first patent was granted, titled: "Method for transiently altering the mass of objects to facilitate their transport or change their stationary apparent weights".[39]

- In 2002, a second patent was granted, titled: "Method And Apparatus For Generating Propulsive Forces Without The Ejection Of Propellant".[40]

- In 2016, a third patent was granted and assigned to the Space Studies Institute, covering the realistic realizations of Mach effects.[41]

Woodward and his associates have claimed since the 1990s to have successfully measured forces at levels great enough for practical use and also claim to be working on the development of a practical prototype thruster. No practical working devices have yet been publicly demonstrated.[2][3][6][22]

Experiments

Test devices

Woodward started to design and build devices using capacitors and a series of thick PZT disks. This ceramic is piezoelectric, so it can be used as an electromechanical actuator to accelerate an object placed against it: its crystalline structure expands when a certain electrical polarity is applied, then contracts when the opposite field is applied.

In the first tests, Woodward simply used a capacitor between two stacks of PZT disks. The capacitor, while being electrically charged to change its internal energy density, is shuttled back and forth between the PZT actuators. Piezoelectric materials can also generate a measurable voltage potential across their two faces when pressed, so Woodward first used some small portions of PZT material as little accelerometers put on the surface of the stack, to precisely tune the device with the power supply. Then Woodward realized that PZT material and the dielectric of a capacitor were very similar, so he built devices that are made exclusively of PZT disks, without any conventional capacitor, applying different signals to different portions of the cylindrical stack. The available picture taken by his graduate student Tom Mahood in 1999 shows a typical all-PZT stack with different disks:[42]

- The outer, thicker disks on the left and right are the "shuttlers".

- The inner stack of thin disks in the center are the shuttled capacitors storing energy during acceleration, where any mass shift would occur.

- The even thinner disks placed between the shuttlers and on both side of the inner disk capacitors are the "squeezometers' acting as accelerometers.

During forward acceleration and before the transient mass change in the capacitor decays, the resultant increased momentum is transferred forward to a bulk "reaction mass" through an elastic collision (the brass end cap on the left in the picture). Conversely, the following decrease in the mass density takes place during its backward movement. While operating, the PZT stack is isolated in a Faraday cage and put on a sensitive torsion arm for thrust measurements, inside a vacuum chamber. Throughout the years, a wide variety of different types of devices and experimental setups have been tested. The force measuring setups have ranged from various load cell devices to ballistic pendulums to multiple torsion arm pendulums, in which movement is actually observed. Those setups have been improved against spurious effects by isolating and canceling thermal transfers, vibration and electromagnetic interference, while getting better current feeds and bearings. Null tests were also conducted.[7]

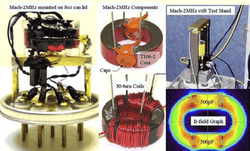

Another type of Mach effect thruster is the Mach-Lorentz thruster (MLT). It uses a charging capacitor embedded in a magnetic field created by a magnetic coil. A Lorentz force, the cross product between the electric field and the magnetic field, appears and acts upon the ions inside the capacitor dielectric. In such electromagnetic experiments, the power can be applied at frequencies of several megahertz, unlike PZT stack actuators where frequency is limited to tens of kilohertz. The photograph shows the components of a Woodward effect test article used in a 2006 experiment.[43]

In the future, Woodward plans to scale thrust levels, switching from the current piezoelectric dielectric ceramics (PZT stacks) to new high-κ dielectric nanocomposite polymers, like PMN, PMN-PT or CCTO. Nevertheless, such materials are new, quite difficult to find, and are electrostrictive, not piezoelectric.[44][45]

In 2013, the Space Studies Institute announced the Exotic Propulsion Initiative, a new project privately funded that aims to replicate Woodward's experiments and then, if proven successful, fully develop exotic propulsion.[46] Gary Hudson, president and CEO of SSI, presented the program at the 2014 NASA Institute for Advanced Concepts Symposium.[47]

Results

From his initial paper onward Woodward has claimed that this effect is detectable with modern technology.[1] He and others have performed and continue to perform experiments to detect the small forces that are predicted to be produced by this effect. So far some groups claim to have detected forces at the levels predicted and other groups have detected forces at much greater than predicted levels or nothing at all. To date there has been no announcement conclusively confirming proof for the existence of this effect or ruling it out.[6]

- In 1990, Woodward's original paper on Mach effects included an experiment with results.[1]

- In 1999, Thomas L. Mahood, Woodward's graduate student from 1997 to 1999, reported thrusts ranging from 0.03 to 15 µN in a setup comprising a torque pendulum in a vacuum chamber, at the Space Technology and Applications International Forum (STAIF) and in his Master of Science in Physics thesis.[48][49]

- As of 2003, Hector Brito of the Instituto Universitario Aeronáutico (IUA) and Sergio Elaskar of the National Scientific and Technical Research Council, Argentina, reported thrusts of about 50 µN.[50][51][52][53]

- In 2004, Paul March of Lockheed Martin Space Operations, who started working in this research field in 1998, presented a successful replication of Woodward's previous experiments at STAIF.[54]

- In 2004, John G. Cramer and coworkers of the University of Washington reported for NASA that they had made an experiment to test Woodward's hypothesis, but that results were inconclusive because their setup was undergoing strong electrical interference which would have masked the effects of the test if it had been conducted.[55]

- In 2006, Paul March and Andrew Palfreyman reported experimental results exceeding Woodward's predictions by one to two orders of magnitude. Items used for this experiment are shown in the photograph above.[43]

- In 2006, Martin Tajmar, Nembo Buldrini, Klaus Marhold and Bernhard Seifert, researchers of the then Austrian Research Centers (now the Austrian Institute of Technology) reported results of a study of the effect using a very sensitive thrust balance. The researchers recommended further tests.[56]

- In 2010, Ricardo Marini and Eugenio Galian of the IUA (same Argentine institute as Hector Brito's) replicated previous experiments, but their results were negative and the measured effects declared as originating from spurious electromagnetic interferences only.[57]

- In 2011, Harold "Sonny" White of the NASA Eagleworks laboratory and his team announced that they were rerunning devices from Paul March's 2006 experiment[43] using force sensors with improved sensitivity.[58]

- In 2012 and 2013, Woodward and Heidi Fearn of California State University, Fullerton, announced the results of more experiments, searching for hypothetical spurious causes that could originate from thermal, electromagnetic or Dean drive effects, which they declared should be ruled out.[7][22][59][60]

Debate

Inertial frames

All inertial frames are in a state of constant, rectilinear motion with respect to one another; they are not accelerating in the sense that an accelerometer at rest in one would detect zero acceleration. Despite their ubiquitous nature, inertial frames are still not fully understood. That they exist is certain, but what causes them to exist – and whether these sources could constitute reaction-media – are still unknown. Marc Millis, of the NASA Breakthrough Propulsion Physics Program, stated " For example, the notion of thrusting without propellant evokes objections of violating conservation of momentum. This, in turn, suggests that space drive research must address conservation of momentum. From there it is found that many relevant unknowns still linger regarding the source of the inertial frames against which conservation is referenced. Therefore, research should revisit the unfinished physics of inertial frames, but in the context of propulsive interactions. "[61] Mach's principle is generally defined within general relativity as "the local inertia frame is completely determined by the dynamic fields in the universe." Rovelli evaluated a number of versions of "Mach's principle" that exist in the literature. Some are partially correct and some have been dismissed as incorrect.[13]

Conservation of momentum

Momentum is defined as mass times velocity. Conservation of momentum applies to velocity terms, usually described in a two dimensional plane with a vector diagram. A vector representing velocity has both direction and magnitude. A requirement for determining conservation of momentum is that an inertial frame or frame of reference for the observer be fixed. Inertial frames are well defined for constant velocity and conservation of momentum holds for all such frames. During acceleration or a change in acceleration, conservation of momentum applies to the local inertial frame (LIF) of instantaneous velocity, not to the proper acceleration a.k.a. coordinate acceleration), as measured by the accelerated observer.

A challenge to the mathematical foundations of Woodward's hypothesis were raised in a paper published by the Oak Ridge National Laboratory in 2001. In the paper, John Whealton noted that the experimental results of Oak Ridge scientists can be explained in terms of force contributions due to time-varying thermal expansion, and stated that a laboratory demonstration produced 100 times the Woodward effect without resorting to non-Newtonian explanations.[62] In response, Woodward published a criticism of Whealton's math and understanding of the physics involved, and built an experiment attempting to demonstrate the flaw.[63]

A rate of change in momentum represents a force, whereby F = ma. Whealton et al. use the technical definition, F=d(mv)/dt, which can be expanded to F=m dv/dt + dm/dt v. This second term has both delta mass and v, which is measured instantaneously; this term will, in general, cancel out the force from the inertial response terms predicted by Woodward. Woodward argued that the dm/dt v term does not represent a physical force on the device, because it vanishes in a frame where the device is momentarily stationary.[24]

In an appendix to his thesis, Mahood argues that the unexpectedly small magnitude of the results in his experiments are a confirmation of the cancellation predicted by Whealton; the results are instead due to higher-order mass transients which are not exactly cancelled.[49] Mahood would later describe this argument as "one of the very few things I've done in my life that I actually regret".[64]

Although the momentum and energy exchange with distant matter guarantees global conservation of energy and momentum, this field exchange is supplied at no material cost, unlike the case with conventional fuels. For this reason, when the field exchange is ignored, a propellantless thruster behaves locally like a free energy device. This is immediately apparent from basic Newtonian analysis: if constant power produces constant thrust, then input energy is linear with time and output (kinetic) energy is quadratic with time. Thus there exists a break-even time (or distance or velocity) of operation, above which more energy is output than is input. The longer it is allowed to accelerate, the more pronounced will this effect become, as simple Newtonian physics predicts.

Considering those conservation issues, a Mach effect thruster relies on Mach's principle, hence it is not an electrical to kinetic transducer, i.e. it does not convert electric energy to kinetic energy. Rather, a MET is a gravinertial transistor that controls the flow of gravinertial flux, in and out of the active mass of the thruster. The primary power into the thruster is contained in the flux of the gravitational field, not the electricity that powers the device. Failing to account for this flux, is much the same as failing to account for the wind on a sail.[65] Mach effects are relativistic by nature, and considering a spaceship accelerating with a Mach effect thruster, the propellant is not accelerating with the ship, so the situation should be treated as an accelerating and therefore non-inertial reference frame, where F does not equal ma. Keith H. Wanser, professor of physics at California State University, Fullerton, published a paper in 2013 concerning the conservation issues of Mach effect thrusters.[66]

Related theories

Woodward's hypothesis is related to Dennis William Sciama's formulation of Mach's principle in which the fluctuations in mass are hypothesized to result from gravity/inertia radiation reactions based on Wheeler–Feynman absorber theory, an interpretation of electrodynamics that starts from the idea that a solution to the electromagnetic field equations has to be symmetric with respect to time-inversion or T-symmetry, as are the field equations themselves. Electromagnetic field equations include but are not limited to Maxwell's equations and Jefimenko's equations.[67][68]

Kenneth Nordtvedt showed in 1988 that gravitomagnetism, which is an effect predicted by general relativity but hasn't been observed yet at that time and was even challenged by the scientific community, is inevitably a real effect because it is a direct consequence of the gravitational vector potential. He subsequently shown that the gravitomagnetism interaction (not to be confused with the Nordtvedt effect), like inertial frame dragging and the Lense–Thirring precession, is typically a Mach effect.[69]

Quantum mechanics

In 2009, Harold "Sonny" White of NASA proposed the Quantum Vacuum Fluctuation (QVF) conjecture, a non-relativistic hypothesis based on quantum mechanics to produce momentum fluxes even in empty outer space.[70] Where Sciama's gravinertial field of Wheeler–Feynman absorber theory is used in the Woodward effect, the White conjecture replaces the Sciama gravinertial field with the quantum electrodynamic vacuum field. The local reactive forces are generated and conveyed by momentum fluxes created in the QED vacuum field by the same process used to create momentum fluxes in the gravinertial field. White uses MHD plasma rules to quantify this local momentum interaction where in comparison Woodward applies condensed matter physics.[58]

Based on the White conjecture, the proposed theoretical device is called a quantum vacuum plasma thruster (QVPT) or Q-thruster. No experiments have been performed to date. Unlike a Mach effect thruster instantaneously exchanging momentum with the distant cosmic matter through the advanced/retarded waves (Wheeler–Feynman absorber theory) of the radiative gravinertial field, Sonny's "Q-thruster" would appear to violate momentum conservation, for the thrust would be produced by pushing off virtual "Q" particle/antiparticle pairs that would annihilate after they have been pushed on. However, it would not necessarily violate the law of conservation of energy, as it requires an electric current to function, much like any "standard" MHD thruster, and cannot produce more kinetic energy than its equivalent net energy input.

Media reaction

Woodward's claims in his papers and in space technology conference press releases of a potential breakthrough technology for spaceflight have generated interest in the popular press[5][71] and university news[72][73] as well as the space news media.[6][74][75][76] Woodward also gave a video interview[77] for the TV show Ancient Aliens, season 6, episode 12.[78] However doubters do exist.[6]

References

- 1 2 3 Woodward, James F. (October 1990). "A new experimental approach to Mach's principle and relativistic gravitation". Foundations of Physics Letters. 3 (5): 497–506. Bibcode:1990FoPhL...3..497W. doi:10.1007/BF00665932.

- 1 2 Woodward, James F. (1990–2000). "Publications 1990-2000" (PDF). Retrieved 3 March 2013.

- 1 2 Woodward, James F. (2000–2005). "Recent Publications". Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- ↑ Cramer, John G. (1999). "An Experimental Test of a Dynamic Mach's Principle Prediction". NASA. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- 1 2 "Smokeless rockets launching soon?". CNET. 2006. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Inglis-Arkell, Esther (3 January 2013). "The Woodward Effect allows for endless supplies of starship fuel". io9. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- 1 2 3 Fearn, Heidi; Woodward, James F. (2013). "Experimental Null test of a Mach Effect Thruster". arXiv:1301.6178

[physics.ins-det].

[physics.ins-det].

- ↑ http://www.ibtimes.co.uk/emdrive-controversial-space-propulsion-will-be-discussed-by-scientists-actual-conference-1582115

- ↑ https://hacked.com/move-emdrive-comes-woodwards-mach-effect-drive/

- 1 2 Woodward, James F. (December 14, 2012). Making Starships and Stargates: The Science of Interstellar Transport and Absurdly Benign Wormholes. Space Exploration, Springer Praxis Books (2013 ed.). NYC: Springer Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4614-5623-0.

- ↑ http://www.its.caltech.edu/~kip/

- ↑ Einstein, A., Letter to Ernst Mach, Zurich, 25 June 1913, in Misner, Charles; Thorne, Kip S. & Wheeler, John Archibald (1973). Gravitation. San Francisco: W. H. Freeman. ISBN 0-7167-0344-0.

- 1 2 Rovelli, Carlo (2004). Quantum Gravity. Cambridge Press. ISBN 978-0521715966.

- ↑ Sciama, D. W. (1953). "On the Origin of Inertia". Royal Astronomical Society. 113: 34–42. Bibcode:1953MNRAS.113...34S. doi:10.1093/mnras/113.1.34.

- ↑ Sciama, D.W. (1964). "The Physical Structure of General Relativity". Rev. Mod. Phys. 36 (1): 463–469. Bibcode:1964RvMP...36..463S. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.36.463.

- ↑ Woodward, James F. (1998). "Radiation Reaction".

- ↑ Woodward, James F.; Mahood, Thomas (June 1999). "What is the Cause of Inertia?". Foundations of Physics Letters. 29 (6): 899–930. doi:10.1023/A:1018821328482.

- ↑ Woodward, James F. (May 2001). "Gravity, Inertia, and Quantum Vacuum Zero Point Fields". Foundations of Physics. 31 (5): 819–835. doi:10.1023/A:1017500513005.

- ↑ Gilman, R.C. (March 12, 1970). "Machian Theory of Inertia and Gravitation". Physical Review D. College Park, Maryland: American Physical Society (published October 15, 1970). 2 (8): 1400–1410. Bibcode:1970PhRvD...2.1400G. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.2.1400.

- ↑ Raine, D.J. (June 1975). "Mach's Principle in general relativity". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. Oxford University Press. 171: 507–528. Bibcode:1975MNRAS.171..507R. doi:10.1093/mnras/171.3.507.

- ↑ Woodward, James F. (1998). "Gravitation: Overview".

- 1 2 3 4 Fearn, Heidi & Woodward, James F. (2012). "Recent Results of an Investigation of Mach Effect Thrusters" (PDF). AIAA Journal. JPC 2012 (48th AIAA/ASME/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference & Exhibit and 10th International Energy Conversion Engineering Conference, Atlanta, Georgia). doi:10.2514/6.2012-3861.

- 1 2 3 Woodward, James F. (February 1995). "Making the universe safe for historians: Time travel and the laws of physics" (PDF). Foundations of Physics Letters. 8 (1): 1–39. Bibcode:1995FoPhL...8....1W. doi:10.1007/BF02187529.

- 1 2 3 4 Woodward, James F. (October 2004). "Flux Capacitors and the Origin of Inertia" (PDF). Foundations of Physics. 34 (10): 1475–1514. Bibcode:2004FoPh...34.1475W. doi:10.1023/B:FOOP.0000044102.03268.46.

- ↑ Ramos, Debra Cano (19 February 2013). "Starships, Stargates, Wormholes and Interstellar Travel: Science Historian and Physicist Contemplates the Challenging Physics of Space Travel". Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- ↑ Zampino, Edward J. (June 1998). "Critical Problems for Interstellar Propulsion Systems" (PDF). NASA. Retrieved 3 March 2013.

- ↑ Johnson, Les (2010). "Interstellar Propulsion Research: Realistic Possibilities and Idealistic Dreams" (PDF). NASA. Retrieved 3 March 2013.

- ↑ Woodward, James F. (August 1997). "Mach's Principle and Impulse Engines: Toward a Viable Physics of Star Trek?". Retrieved 1 February 2013.

- ↑ Mills, Marc G. (August 1997). "NASA Breakthrough Propulsion Physics Workshop Proceedings". NASA: 367–374. Retrieved 1 February 2013.

- ↑ Woodward, James F.; Mahood, Thomas L.; March, Paul (July 2001). "Rapid Spacetime Transport and Machian Mass Fluctuations: Theory and Experiment" (PDF). JPC 2001 Proceedings. 37th AIAA/ASME Joint Propulsion Conference, Salt Lake City, Utah. American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics. doi:10.2514/6.2001-3907.

- ↑ Woodward, James F. (February 2003). "Breakthrough Propulsion and the Foundations of Physics". Foundations of Physics Letters. 16 (1): 25–40. doi:10.1023/A:1024198022814.

- ↑ Woodward, James F. (February 2004). "Life Imitating "Art": Flux Capacitors, Mach Effects, and Our Future in Spacetime". AIP Conference Proceedings. Space Technology Applications International Forum (STAIF 2004), Albuquerque, New Mexico. 699. American Institute of Physics. pp. 1127–1137. doi:10.1063/1.1649682.

- ↑ Woodward, James F. (February 2005). "Tweaking Flux Capacitors". AIP Conference Proceedings. Space Technology Applications International Forum (STAIF 2005), Albuquerque, New Mexico. 746. American Institute of Physics. pp. 1345–1352. doi:10.1063/1.1867264.

- ↑ March, Paul (February 2007). "Mach‐Lorentz Thruster Spacecraft Applications". AIP Conference Proceedings. Space Technology and Applications International Forum-STAIFF 2007, Albuquerque, New Mexico. 880. College Park, Maryland: American Institute of Physics. pp. 1063–1070. doi:10.1063/1.2437551.

- 1 2 Alcubierre, Miguel (1994). "The warp drive: hyper-fast travel within general relativity". Classical and Quantum Gravity. 11 (5): L73–L77. arXiv:gr-qc/0009013

. Bibcode:1994CQGra..11L..73A. doi:10.1088/0264-9381/11/5/001.

. Bibcode:1994CQGra..11L..73A. doi:10.1088/0264-9381/11/5/001.

- 1 2 Morris, Michael; Thorne, Kip; Yurtsever, Ulvi (1988). "Wormholes, Time Machines, and the Weak Energy Condition" (PDF). Physical Review Letters. 61 (13): 1446–1449. Bibcode:1988PhRvL..61.1446M. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.61.1446. PMID 10038800.

- ↑ Woodward, James F. (April 1997). "Twists of fate: Can we make traversable wormholes in spacetime?" (PDF). Foundations of Physics Letters. 10 (2): 153–181. Bibcode:1997FoPhL..10..153W. doi:10.1007/BF02764237.

- ↑ Woodward, James F. (2011). "Making Stargates: The Physics of Traversable Absurdly Benign Wormholes" (PDF). Physics Procedia. Space, Propulsion & Energy Sciences International Forum-SPESIF 2011. 20. Elsevier Press. pp. 24–46. doi:10.1016/j.phpro.2011.08.003.

- ↑ US patent 5280864, James F. Woodward, "Method for transiently altering the mass of objects to facilitate their transport or change their stationary apparent weights", issued 1994-01-25

- ↑ US patent 6347766, James Woodward & Thomas Mahood, "Method And Apparatus For Generating Propulsive Forces Without The Ejection Of Propellant", issued 2002-02-19

- ↑ US patent 9287840, James F. Woodward, "Parametric amplification and switched voltage signals for propellantless propulsion", issued 2016-03-15, assigned to Space Studies Institute

- ↑ Mahood, Thomas. "Graduate studies in Physics at Cal State University, Fullerton". Retrieved 27 January 2014.

- 1 2 3 March, Paul; Palfreyman, Andrew (January 2006). "The Woodward Effect: Math Modeling and Continued Experimental Verifications at 2 to 4 MHz". AIP Conference Proceedings. Space Technology and Applications International Forum-STAIFF 2006, Albuquerque, New Mexico. 813. American Institute of Physics. pp. 1321–1332. doi:10.1063/1.2169317.

- ↑ "Scaling Mach Effect Propulsion". nextbigfuture.com. 16 August 2012.

- ↑ Lunkenheimer, Peter & Al. (2009). "Colossal dielectric constant up to GHz at room temperature". Applied Physics Letters. 91: 122903. arXiv:0811.1556v2

. Bibcode:2009ApPhL..94l2903K. doi:10.1063/1.3105993.

. Bibcode:2009ApPhL..94l2903K. doi:10.1063/1.3105993. |article=ignored (help) - ↑ "Exotic Propulsion Initiative". Space Studies Institute. 30 April 2013. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

- ↑ Exotic Propulsion Initiative by Gary Hudson, NIAC 2014 on YouTube

- ↑ Mahood, Thomas L. (February 1999). "Propellantless propulsion: Recent experimental results exploiting transient mass modification" (PDF). AIP Conference Proceedings. Space Technology and Applications International Forum-STAIFF 2000, Albuquerque, New Mexico. 458. American Institute of Physics. pp. 1014–1020. doi:10.1063/1.57494.

- 1 2 Mahood, Thomas Louis (November 11, 1999). A torsion pendulum investigation of transient Machian effects (PDF) (M.Sc. thesis). California State University, Fullerton.

- ↑ Brito, Hector H.; Elaskar, Sergio A. (July 2003). "Direct Experimental Evidence of Electromagnetic Inertia Manipulation Thrusting". Joint Propulsion Conference Proceedings. 39th AIAA/ASME/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference and Exhibit, Huntsville, AL. American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics. doi:10.2514/6.2003-4989.

- ↑ Brito, Hector H. (April 2004). "Experimental status of thrusting by electromagnetic inertia manipulation". Acta Astronautica. International Academy of Astronautics. 54 (8): 547–558. Bibcode:2004AcAau..54..547B. doi:10.1016/S0094-5765(03)00225-X.

- ↑ Brito, Hector H.; Elaskar, Sergio A. (February 2005). "Overview of Theories and Experiments on Electromagnetic Inertia Manipulation Propulsion". AIP Conference Proceedings. Space Technology and Applications International Forum-STAIFF 2005, Albuquerque, New Mexico. 746. American Institute of Physics. pp. 1395–1402. doi:10.1063/1.1867270.

- ↑ Brito, Hector H.; Elaskar, Sergio A. (March–April 2007). "Direct Experimental Evidence of Electromagnetic Inertia Manipulation Thrusting". Journal of Propulsion and Power. American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics. 23 (2): 487–494. doi:10.2514/1.18897.

- ↑ March, Paul (February 2004). "Woodward Effect Experimental Verifications". AIP Conference Proceedings. Space Technology and Applications International Forum-STAIFF 2004, Albuquerque, New Mexico. 699. American Institute of Physics. pp. 1138–1145. doi:10.1063/1.1649683.

- ↑ Cramer, John; Millis, Marc G.; Fey, Curran W.; Cassisi, Damon V. (October 2004). Tests of Mach's Principle With a Mechanical Oscillator (Report). Glenn Research Center: NASA.

- ↑ Buldrini, Nembo; Tajmar, Martin; Marhold, Klaus; Seifert, Bernhard (February 2006). "Experimental Study of the Machian Mass Fluctuation Effect Using a μN Thrust Balance" (PDF). AIP Conference Proceedings. Space Technology and Applications International Forum-STAIFF 2006, Albuquerque, New Mexico. 813. American Institute of Physics. pp. 1313–1320. doi:10.1063/1.2169316.

- ↑ Marini, Ricardo L.; Galian, Eugenio S. (November–December 2010). "Torsion Pendulum Investigation of Electromagnetic Inertia Manipulation Thrusting". Journal of Propulsion and Power. 26 (6): 1283–1290. doi:10.2514/1.46541.

- 1 2 Dr. Harold "Sonny" White; Paul March; Nehemiah Williams; William O'Neill (December 2, 2011). "Eagleworks Laboratories: Advanced Propulsion Physics Research" (PDF). NASA. Retrieved 31 January 2013.

- ↑ Fearn, Heidi (October 5, 2012). "Recent Theory & Experimental work on Mach Effect Thrusters" (PDF). Proceedings. Advanced Space Propulsion Workshop (ASPW 2012), Marshall Space Flight Center, Huntsville, AL. NASA.

- ↑ Fearn, Heidi; Woodward, James F. (29 July 2013). Mehtapress, ed. "Experimental Null test of a Mach Effect Thruster". Journal of Space Exploration. 2 (2). arXiv:1301.6178

. Bibcode:2013arXiv1301.6178F.

. Bibcode:2013arXiv1301.6178F. - ↑ Millis, M. G. (2010). "Progress in Revolutionary Propulsion Physics". arXiv:1101.1063

.

.

- ↑ Whealton, J.H. (4 September 2001). "Revised Theory of Transient Mass Fluctuations" (PDF). United States Department of Energy. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- ↑ Woodward, James F. "Answer to ORNL". NasaSpaceflight.com. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- ↑ Mahood, Thomas. "Graduate studies in Physics at Cal State University, Fullerton". Other Hand. Retrieved 2014-10-13.

- ↑ Stahl, Ron (21 February 2015). "Mach-Effect physics conservation concerns: 3 important observations". Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- ↑ Wanser, Keith H. (29 July 2013). Mehtapress, ed. "Center of mass acceleration of an isolated system of two particles with time variable masses interacting with each other via Newton's third law internal forces: Mach effect thrust 1" (PDF). Journal of Space Exploration. 2 (2).

- ↑ Sciama, D. W. (1953). "On the Origin of Inertia". Royal Astronomical Society. 113: 34–42. Bibcode:1953MNRAS.113...34S. doi:10.1093/mnras/113.1.34.

- ↑ Sciama, D. W. (1971). Modern Cosmology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. OCLC 6931707.

- ↑ Nordtvedt, Ken (November 1988). "Existence of the gravitomagnetic interaction". International Journal of Theoretical Physics. 27 (11): 1395–1404. doi:10.1007/BF00671317.

- ↑ Harold (Sonny) White (October 2009). "Revolutionary Propulsion & Power for the Next Century of Space Flight" (PDF). Von Braun Symposium.

- ↑ Platt, Charles (24 November 2014). "Strange thrust: the unproven science that could propel our children into space". Boing Boing.

- ↑ "Starships, Stargates, Wormholes and Interstellar Travel". CSUF News. 19 February 2013.

- ↑ "Faculty Author on the Science of Deep Space Travel". CSUF News. 10 April 2013.

- ↑ Szames, Alexandre (January 2000). "Strange thrust: the unproven science that could propel our children into space". Interavia Business & Technology. p. 30. ISSN 1423-3215.

- ↑ "The Space Show: Dr. James Woodward". thespaceshow.com.

- ↑ Gilster, Paul (28 August 2006). "Gravity, Inertia, Exotica". Tau Zero Foundation. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- ↑ Mach effect: warp drives and stargates by Jim Woodward on Vimeo

- ↑ "Ancient Aliens Episode Guide". History channel. Retrieved October 1, 2013.

Bibliography

- Adelberger, E. G., Heckel, B. R., Smith, G., Su, Y., and Swanson, H. E. (1990-Sep-20). "Eötvös experiments, lunar ranging and the strong equivalence principle", Nature 347 (6290): 261–263, Bibcode 1990Natur.347..261A, doi:10.1038/347261a0

- Alcubierre, Miguel (1994). "The warp drive: hyper-fast travel within general relativity". Classical and Quantum Gravity 11 (5): L73–L77. arXiv:gr-qc/0009013. Bibcode 1994CQGra..11L..73A. doi:10.1088/0264-9381/11/5/001.

- Brito, Hector H.; Elaskar, Sergio A. (July 2003). "Direct Experimental Evidence of Electromagnetic Inertia Manipulation Thrusting". Joint Propulsion Conference Proceedings. American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics. doi:10.2514/6.2003-4989.

- Brito, Hector H. (April 2004). "Experimental status of thrusting by electromagnetic inertia manipulation". Acta Astronautica (International Academy of Astronautics) 54 (8): 547–558. doi:10.1016/S0094-5765(03)00225-X.

- Brito, Hector H.; Elaskar, Sergio A. (February 2005). "Overview of Theories and Experiments on Electromagnetic Inertia Manipulation Propulsion". AIP Conference Proceedings. 746. American Institute of Physics. pp. 1395–1402. doi:10.1063/1.1867270.

- Brito, Hector H.; Elaskar, Sergio A. (March–April 2007). "Direct Experimental Evidence of Electromagnetic Inertia Manipulation Thrusting". Journal of Propulsion and Power (American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics) 23 (2): 487–494. doi:10.2514/1.18897.

- Buldrini, Nembo; Tajmar, Martin; Marhold, Klaus; Seifert, Bernhard (February 2006). "Experimental Study of the Machian Mass Fluctuation Effect Using a μN Thrust Balance". AIP Conference Proceedings. 813. American Institute of Physics. pp. 1313–1320. doi:10.1063/1.2169316.

- Cramer, John G. (1999). "An Experimental Test of a Dynamic Mach's Principle Prediction". NASA. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- Cramer, John; Millis, Marc G.; Fay, Curran W.; Casissi, Damon V. (October 2004). Tests of Mach's Principle With a Mechanical Oscillator (Report). NASA/CR-2004-213310, E-14770. Glenn Research Center: NASA.

- Einstein, A., Letter to Ernst Mach, Zurich, (25 June 1923), in Misner, Charles; Thorne, Kip S.; and Wheeler, John Archibald (1973). Gravitation. San Francisco: W. H. Freeman. ISBN 0-7167-0344-0.

- Fearn, Heidi and Woodward, James F. (2012). "Recent Results of an Investigation of Mach Effect Thrusters". AIAA Journal JPC 2012 (48th AIAA/ASME/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference & Exhibit and 10th International Energy Conversion Engineering Conference, Atlanta, Georgia). doi:10.2514/6.2012-3861.

- Fearn, Heidi; Woodward, James F. (2013). "Experimental Null test of a Mach Effect Thruster". arXiv:1301.6178 [physics.ins-det].

- Gilman, R. C. (March 12, 1970). "Machian Theory of Inertia and Gravitation". Physical Review D (College Park, Maryland: American Physical Society) 2 (8): 1400–1410. October 15, 1970. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.2.1400.

- Glister, Paul (28 August 2006). "Gravity, Inertia, Exotica". Tau Zero Foundation. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- Inglis-Arkell, Esther (3 January 2013). "The Woodward Effect allows for endless supplies of starship fuel". io9. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- Johnson, Les (2010). "Interstellar Propulsion Research: Realistic Possibilities and Idealistic Dreams". NASA. Retrieved 3 March 2013.

- Lunkenheimer, Peter and Al. (2009). "Colossal dielectric constant up to GHz at room temperature". Applied Physics Letters 91. arXiv:0811.1556v2. doi:10.1063/1.3105993.

- Mahood, Thomas L. (February 1999). "Propellantless propulsion: Recent experimental results exploiting transient mass modification". AIP Conference Proceedings. 458. American Institute of Physics. pp. 1014–1020. doi:10.1063/1.57494.

- Mahood, Thomas Louis (November 11, 1999). A torsion pendulum investigation of transient Machian effects (M.Sc. thesis). California State University, Fullerton.

- March, Paul (February 2004). "Woodward Effect Experimental Verifications". AIP Conference Proceedings. 699. American Institute of Physics. pp. 1138–1145. doi:10.1063/1.1649683.

- March, Paul; Palfreyman, Andrew (January 2006). "The Woodward Effect: Math Modeling and Continued Experimental Verifications at 2 to 4 MHz". AIP Conference Proceedings. 813. American Institute of Physics. pp. 1321–1332. doi:10.1063/1.2169317.

- March, Paul (February 2007). "Mach‐Lorentz Thruster Spacecraft Applications". AIP Conference Proceedings. 880. College Park, Maryland: American Institute of Physics. pp. 1063–1070. doi:10.1063/1.2437551.

- Marini, Ricardo L.; Galian, Eugenio S. (November–December 2010). "Torsion Pendulum Investigation of Electromagnetic Inertia Manipulation Thrusting". Journal of Propulsion and Power 26 (6): 1283–1290.. doi:10.2514/1.46541.

- Mills, Marc G. (August 1997). NASA Breakthrough Propulsion Physics Workshop Proceedings. NASA. pp. 367–374. Retrieved 1 February 2013.

- Millis, M. G. (2010). "Progress in Revolutionary Propulsion Physics". International Astronautical Federation. Retrieved 28 February 2013.

- "Wormholes, time machines, and the weak energy condition". Phys. Rev. Lett. 61: 1446–1449. September 1988. Bibcode:1988PhRvL..61.1446M. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.61.1446. PMID 10038800..

- Raine, D. J. (June 1975). "Mach's principle in general relativity". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society (Oxford University Press) 171: 507–528. Bibcode 1975MNRAS.171..507R.

- Ramos, Debra Cano (19 February 2013). "Starships, Stargates, Wormholes and Interstellar Travel: Science Historian and Physicist Contemplates the Challenging Physics of Space Travel"

- Rovelli, Carlo (2004). Quantum Gravity. Cambridge Press. ISBN ISBN 978-0521715966.

- Sciama, D. W. (1953). "On the Origin of Inertia". Royal Astronomical Society 113: 34–42. Bibcode 1953MNRAS.113...34S.

- Sciama, D. W. (1964). "The Physical Structure of General Relativity". Rev. Mod. Phys. 36 (1): 463–469. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.36.463.

- Sciama, D. W. (1953). "On the Origin of Inertia". Royal Astronomical Society 113: 34. Bibcode 1953MNRAS.113...34S.

- Sciama, D. W. (1971). Modern Cosmology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. OCLC 6931707.

- Whealton, J. H. (4 September 2001). "Revised Theory of Transient Mass Fluctuations". United States Department of Energy. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- White, Harold (Sonny) (October 2009). "Revolutionary Propulsion & Power for the Next Century of Space Flight" (PDF). Von Braun Symposium. ^ a b c

- White, Harold "Sonny"; Paul March; Nehemiah Williams; William O'Neill (December 2, 2011). "Eagleworks Laboratories: Advanced Propulsion Physics Research". NASA. Retrieved 31 January 2013.

- Will, Clifford M. (2006) "The Confrontation between General Relativity and Experiment" URL= http://relativity.livingreviews.org/Articles/lrr-2006-3/

- Williams, J.G., Newhall, X. X., and Dickey, J. O. (1996), "Relativity parameters determined from lunar laser ranging", Phys. Rev. D 53: 6730–6739, Bibcode 1996PhRvD..53.6730W, doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.53.6730

- Williams, James G. and Dickey, Jean O.. (2002) "Lunar Geophysics, Geodesy, and Dynamics" (PDF). ilrs.gsfc.nasa.gov. Retrieved 2008-05-04. 13th International Workshop on Laser Ranging, October 7–11, 2002, Washington, D. C.

- Woodward, James F. (1990-2000). "Publications 1990-2000" (PDF). Retrieved 3 March 2013.

- Woodward, James F. (2000-2005). "Recent Publications". Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- Woodward, James F. (October 1990). "A new experimental approach to Mach's principle and relativistic gravitation". Foundations of Physics Letters 3 (5): 497–506. Retrieved 1 February 2013.

- Woodward, James F. (February 1995). "Making the universe safe for historians: Time travel and the laws of physics". Foundations of Physics Letters 8 (1): 1–39. doi:10.1007/BF02187529.

- Woodward, James F. (April 1997). "Twists of fate: Can we make traversable wormholes in spacetime?". Foundations of Physics Letters 10 (2): 153–181. doi:10.1007/BF02764237.

- Woodward, James F. (August 1997). "Mach's Principle and Impulse Engines: Toward a Viable Physics of Star Trek?". Retrieved 1 February 2013.

- Woodward, James F. (1998). "Radiation Reaction".

- Woodward, James F. (1998). "Gravitation: Overview".

- Woodward, James F.; Mahood, Thomas (June 1999). "What is the Cause of Inertia?". Foundations of Physics Letters 29 (6): 899–930 l doi=10.1023/A:1018821328482.

- Woodward, James F. (May 2001). "Gravity, Inertia, and Quantum Vacuum Zero Point Fields". Foundations of Physics 31 (5): 819–835. doi:10.1023/A:1017500513005.

- Woodward, James F.; Mahood, Thomas L.; March, Paul (July 2001). "Rapid Spacetime Transport and Machian Mass Fluctuations: Theory and Experiment". JPC 2001 Proceedings. American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics. doi:10.2514/6.2001-3907.

- Woodward, James F. (2001) "Answer to ORNL". NasaSpaceflight.com. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- Woodward, James F. (February 2003). "Breakthrough Propulsion and the Foundations of Physics". Foundations of Physics Letters 16 (1): 25–40. doi:10.1023/A:1024198022814.

- Woodward, James F. (February 2004). "Life Imitating "Art": Flux Capacitors, Mach Effects, and Our Future in Spacetime". AIP Conference Proceedings. 699. American Institute of Physics. pp. 1127–1137. doi:10.1063/1.1649682.

- Woodward, James F. (October 2004). "Flux Capacitors and the Origin of Inertia". Foundations of Physics 34 (10): 1475–1514. doi:10.1023/B:FOOP.0000044102.03268.46.

- Woodward, James F. (February 2005). "Tweaking Flux Capacitors". AIP Conference Proceedings. 746. American Institute of Physics. pp. 1345–1352. doi:10.1063/1.1867264.

- Woodward, James F. (2011). "Making Stargates: The Physics of Traversable Absurdly Benign Wormholes". Physics Procedia. 20. Elsevier Press. pp. 24–46. doi:10.1016/j.phpro.2011.08.003.

- Woodward, James F. (December 14, 2012). Making Starships and Stargates: The Science of Interstellar Transport and Absurdly Benign Wormholes. Space Exploration, Springer Praxis Books (2013 ed.). NYC: Springer Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4614-5623-0.

- Zampino, Edward J. (June 1998). "Critical Problems for Interstellar Propulsion Systems". NASA. Retrieved 3 March 2013.

Bibliography other works

- "Interstellar propulsion: the quest for empty space".NASA

- "Scaling Mach Effect Propulsion". nextbigfuture.com. 16 August 2012.

- "Smokeless rockets launching soon?". CNET. 2006. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- "US Patent #5,280,864 Method And Apparatus To Generate Thrust By Inertial Mass Variance". 25 January 1994. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- "US Patent #6,347,766 "Method And Apparatus For Generating Propulsive Forces Without The Ejection Of Propellant" James Woodward and Thomas Mahood". Retrieved 23 December 2008.

- "The Space Show: Dr. James Woodward". thespaceshow.com.

Further reading

- Barbour, Julian; and Pfister, Herbert (eds.) (1995). Mach's principle: from Newton's bucket to quantum gravity. Boston: Birkhäuser. ISBN 3-7643-3823-7. (Einstein studies, vol. 6)

- McEachern, Mary Margaret (2009). From Here to Eternity and Back: Are Traversable Wormholes Possible?

- Rovelli, Carlo (2004). Quantum Gravity. Cambridge Press. ISBN ISBN 978-0521715966.

- Sciama, D. W. (1971). Modern Cosmology. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521287210.

- Thorne, Kip S. (2012) Classical Black Holes: The Nonlinear Dynamics of Curved Spacetime" Science 337 (6094). pp. 536–538. ISSN 0036-8075

- Woodward, James F. (2012). Making Starships and Stargates: The Science of Interstellar Transport and Absurdly Benign Wormholes. Springer Praxis Books. ISBN 978-1461456223.

- LIGO http://www.ligo.org/science.php