Zeno of Elea

| Zeno of Elea | |

|---|---|

Zeno shows the Doors to Truth and Falsity (Veritas et Falsitas). Fresco in the Library of El Escorial, Madrid. | |

| Born |

c. 490 BC Elea |

| Died |

c. 430 BC (aged around 60) Elea or Syracuse |

| Era | Pre-Socratic philosophy |

| Region | Western Philosophy |

| School | Eleatic school |

Main interests | Metaphysics, Ontology |

Notable ideas | Zeno's paradoxes |

|

Influences

| |

|

Influenced

| |

Zeno of Elea (/ˈziːnoʊ əv ˈɛliə/; Greek: Ζήνων ὁ Ἐλεάτης; c. 490 – c. 430 BC) was a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher of Magna Graecia and a member of the Eleatic School founded by Parmenides. Aristotle called him the inventor of the dialectic.[1] He is best known for his paradoxes, which Bertrand Russell has described as "immeasurably subtle and profound".[2]

Life

Little is known for certain about Zeno's life. Although written nearly a century after Zeno's death, the primary source of biographical information about Zeno is Plato's Parmenides[3] and he is also mentioned in Aristotle's Physics.[4] In the dialogue of Parmenides, Plato describes a visit to Athens by Zeno and Parmenides, at a time when Parmenides is "about 65," Zeno is "nearly 40" and Socrates is "a very young man".[5] Assuming an age for Socrates of around 20, and taking the date of Socrates' birth as 469 BC gives an approximate date of birth for Zeno of 490 BC. Plato says that Zeno was "tall and fair to look upon" and was "in the days of his youth … reported to have been beloved by Parmenides."[5]

Other perhaps less reliable details of Zeno's life are given by Diogenes Laërtius in his Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers,[6] where it is reported that he was the son of Teleutagoras, but the adopted son of Parmenides, was "skilled to argue both sides of any question, the universal critic," and that he was arrested and perhaps killed at the hands of a tyrant of Elea.

| “ |

Your noble wish, O Zeno, was to slay |

” |

| — Diogenes Laertius, Life of Zeno, the Eleatic[7][8] | ||

According to Diogenes Laertius, Zeno conspired to overthrow Nearchus the tyrant.[9] Eventually, Zeno was arrested and tortured.[10] According to Valerius Maximus, when he was tortured to reveal the name of his colleagues in conspiracy Zeno refused to reveal their names, although he said he did have a secret that would be advantageous for Nearchus to hear. When Nearchus leaned in to listen to the secret, Zeno bit his ear. He "did not let go until he lost his life and the tyrant lost that part of his body."[11][12] Within Men of the Same Name, Demetrius said it was the nose that was bit off instead.[13]

Zeno may have also interacted with other tyrants. According to Laertius, Heraclides Lembus, within his Satyrus, said these events occurred against Diomedon instead of Nearchus.[9] Valerius Maximus recounts a conspiracy against the tyrant Phalaris, but this would be impossible as Phalaris had died before Zeno was even born.[12][14] According to Plutarch, Zeno attempted to kill the tyrant Demylus. After failing, he had, "with his own teeth bit off his tongue, he spit it in the tyrant’s face."[15]

Works

Although many ancient writers refer to the writings of Zeno, none of his works survive intact. The main sources on the nature of Zeno's arguments on motion, in fact, come from the writings of Aristotle and Simplicius of Cilicia.[16]

Plato says that Zeno's writings were "brought to Athens for the first time on the occasion of" the visit of Zeno and Parmenides.[5] Plato also has Zeno say that this work, "meant to protect the arguments of Parmenides",[5] was written in Zeno's youth, stolen, and published without his consent. Plato has Socrates paraphrase the "first thesis of the first argument" of Zeno's work as follows: "if being is many, it must be both like and unlike, and this is impossible, for neither can the like be unlike, nor the unlike like."[5]

According to Proclus in his Commentary on Plato's Parmenides, Zeno produced "not less than forty arguments revealing contradictions",[17] but only nine are now known.

Zeno's arguments are perhaps the first examples of a method of proof called reductio ad absurdum, literally meaning to reduce to the absurd. Parmenides is said to be the first individual to implement this style of argument. This form of argument soon became known as the epicheirema (ἐπιχείρημα). In Book VII of his Topics, Aristotle says that an epicheirema is "a dialectical syllogism." It is a connected piece of reasoning which an opponent has put forward as true. The disputant sets out to break down the dialectical syllogism. This destructive method of argument was maintained by him to such a degree that Seneca the Younger commented a few centuries later, "If I accede to Parmenides there is nothing left but the One; if I accede to Zeno, not even the One is left."[18]

Zeno is also regarded as the first philosopher who dealt with the earliest attestable accounts of mathematical infinity.

According to Sir William Smith, in Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology (1870)[19]

- Others content themselves with reckoning Parmenides as well as Zeno as belonging to the Pythagorean school, or with speaking of a Parraenidean life, in the same way as a Pythagorean life is spoken of; and even the censorious Timon allows Parmenides to have been a high-minded man; while Plato speaks of him with veneration, and Aristotle and others give him an unqualified preference over the rest of the Eleatics.

Zeno's paradoxes

Zeno's paradoxes have puzzled, challenged, influenced, inspired, infuriated, and amused philosophers, mathematicians, and physicists for over two millennia. The most famous are the arguments against motion described by Aristotle in his Physics.[20]

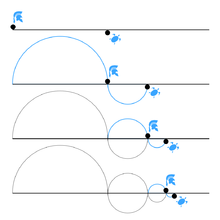

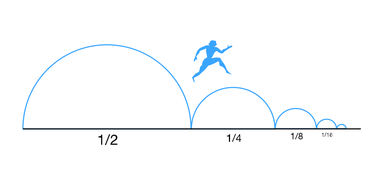

Achilles and the tortoise

Achilles and the tortoise The dichotomy

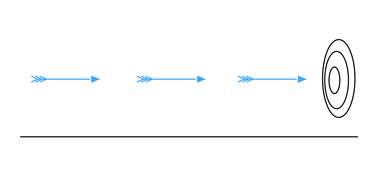

The dichotomy The arrow

The arrow The moving rows

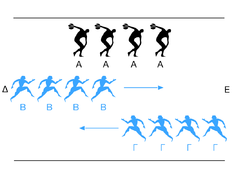

The moving rows

See also

Notes

- ↑ Diogenes Laërtius, 8.57, 9.25

- ↑ Russell (1996 [1903]), p. 347: "In this capricious world nothing is more capricious than posthumous fame. One of the most notable victims of posterity's lack of judgement is the Eleatic Zeno. Having invented four arguments all immeasurably subtle and profound, the grossness of subsequent philosophers pronounced him to be a mere ingenious juggler, and his arguments to be one and all sophisms. After two thousand years of continual refutation, these sophisms were reinstated, and made the foundation of a mathematical renaissance..."

- ↑ Plato (c. 380 – 367 BC). Parmenides, translated by Benjamin Jowett. Internet Classics Archive.

- ↑ Aristotle (c. mid 4th century BC), Physics 233a and 239b

- 1 2 3 4 5 Plato, Parmenides 127b–e

- ↑ Diogenes Laërtius. The Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers, translated by C.D. Yonge. London: Henry G. Bohn, 1853. Scanned and edited for Peithô's Web.

- ↑ http://www.mlahanas.de/Greeks/Paradoxa.htm

- ↑ http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0258%3Abook%3D9%3Achapter%3D5

- 1 2 Diogenes Laertius, Lives of Eminent Philosophers. Book IX.5.26

- ↑ Boethius, The Consolation of Philosophy. Book 1.III

- ↑ Valerius Maximus, Memorable Deeds and Sayings. Foreign Stories 3. ext. 3.

- 1 2 Maximus, Valerius; Walker, Henry J. (2004). Memorable Deeds and Sayings: One Thousand Tales from Ancient Rome. Hackett Pub. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-87220-674-8.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertius, Lives of Eminent Philosophers. Book IX.5.27

- ↑ Valerius Maximus, Memorable Deeds and Sayings. Foreign Stories 3. ext. 2.

- ↑ Plutarch, Against Colotes

- ↑ Cajori, Florian (1920). "The Purpose of Zeno's Arguments on Motion". Isis. 3 (1): 7–20. doi:10.1086/357889.

- ↑ Proclus, Commentary on Plato's Parmenides, p. 29

- ↑ Zeno in The Presocratics, Philip Wheelwright ed., The Odyssey Press, 1966, pp. 106–107.

- ↑

Smith, William, ed. (1870). "Parmenides". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. p. 125.

Smith, William, ed. (1870). "Parmenides". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. p. 125.

- ↑ Aristotle. Physics, translated by R.P. Hardie and R.K. Gaye. Internet Classics Archive.

References

- Plato; Fowler, Harold North (1925) [1914]. Plato in twelve volumes. 8, The Statesman.(Philebus).(Ion). Loeb Classical Library. trans. W. R. M. Lamb. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard U.P. ISBN 978-0-434-99164-8. OCLC 222336129.

- Proclus; Morrow, Glenn R.; Dillon, John M. (1992) [1987]. Proclus' Commentary on Plato's Parmenides. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-02089-1. OCLC 27251522.

- Russell, Bertrand (1996) [1903]. The Principles of Mathematics. New York, NY: Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-31404-5. OCLC 247299160.

- Hornschemeier, Paul (2007). The Three Paradoxes. Seattle, WA: Fantagraphics Books.

Further reading

- Jonathan Barnes The Presocratic Philosophers, 2nd edition, London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1982.

- G. E. L. Owen. Zeno and the Mathematicians, Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society (1957-8).

- Mark Sainsbury, Paradoxes. Cambridge, 1988.

- Wesley C. Salmon, ed. Zeno's Paradoxes Indianapolis, 1970.

- Gregory Vlastos, Zeno of Elea, in The Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Paul Edwards, ed.), New York, 1967.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Zeno of Elea |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Zeno of Elea. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Palmer, John. "Zeno of Elea". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Zeno of Elea – MacTutor History of Mathematics

- Plato's Parmenides.

- Aristotle's Physics.

Laërtius, Diogenes (1925). "Others: Zeno of Elea". Lives of the Eminent Philosophers. 2:9. Translated by Hicks, Robert Drew (Two volume ed.). Loeb Classical Library.

Laërtius, Diogenes (1925). "Others: Zeno of Elea". Lives of the Eminent Philosophers. 2:9. Translated by Hicks, Robert Drew (Two volume ed.). Loeb Classical Library.- Fragments of Zeno