Zwitterion

In chemistry, a zwitterion (/ˈtsvɪtər.aɪ.ən/ TSVIT-ər-eye-ən; from German zwitter [ˈtsvɪtɐ], meaning "hermaphrodite"), formerly called a dipolar ion, is a neutral molecule with both positive and negative electrical charges. (In some cases multiple positive and negative charges may be present.) Zwitterions are distinct from molecules that have dipoles at different locations within the molecule. Zwitterions are sometimes called inner salts.[1]

Unlike simple amphoteric compounds that may only form either a cationic or anionic species, a zwitterion simultaneously has both ionic states.[2]

Examples

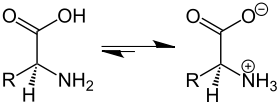

Amino acids are the best-known examples of zwitterions. These compounds contain an ammonium and a carboxylate group, and can be viewed as arising via a kind of intramolecular acid–base reaction: The amine group deprotonates the carboxylic acid.

- NH

2RCHCO

2H ⇌ NH+

3RCHCO−

2

The zwitterionic structure of glycine in the solid state has been confirmed by neutron diffraction measurements.[3] At least in some cases, the zwitterionic form of amino acids also persists in the gas phase.[4]

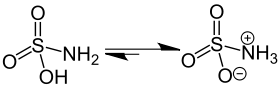

In addition to the amino acids, many other compounds that contain both acidic and basic centres tautomerize to the zwitterionic form. Examples, such as bicine and tricine, contain a basic secondary or tertiary amine fragment together with a carboxylic acid fragment. Neutron diffraction measurements show that solid sulfamic acid exists as a zwitterion.[5] Many alkaloids, such as LSD and psilocybin, exist as zwitterions because they contain carboxylates and ammonium centres.

Many zwitterions contain quaternary ammonium cations. Since it lacks N–H bonds, the ammonium center cannot participate in tautomerization. Zwitterions containing quaternary-ammonium centers are common in biology, a common example are the betaines, which serve as electrolytes in fish. The membrane-forming phospholipids are also commonly zwitterions. The polar head groups in these compounds are zwitterions, resulting from the presence of the anionic phosphate and cationic quaternary ammonium centres.[6]

Related compounds

Dipolar compounds are usually not classified as zwitterions. For example, amine oxides, which are often written as R3N+O−, are not zwitterions in terms of the definition,[1] which specifies that there are unit electrical charges on atoms. The distinction lies in the fact that the plus and minus signs on the amine oxide signify formal charges, not electrical charges. Formal charges are used in valence bond theory for some canonical forms used to construct a resonance hybrid. In fact another theoretical representation of an amine oxide uses a dative covalent bond ≡N→O with no formal charges. Other compounds that are sometimes referred to as zwitterions, mistakenly according to the definition above, include nitrones and "dipolar compounds", such as a 1,2-dipole (ylide) and a 1,3-dipole.[7]

References

- 1 2 IUPAC Gold Book zwitterionic compounds/zwitterions

- ↑ "Definition of amphoteric" (2014), Chemicool. Retrieved 2016-06-14.

- ↑ Jönsson, P.-G.; Kvick, Å. (1972). "Precision neutron diffraction structure determination of protein and nucleic acid components. III. The crystal and molecular structure of the amino acid α-glycine". Acta Crystallogr. B. 28 (6): 1827–1833. doi:10.1107/S0567740872005096.

- ↑ Price, William D.; Jockusch, Rebecca A.; Williams, Evan R. (1997). "Is Arginine a Zwitterion in the Gas Phase?". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 119 (49): 11988–11989. doi:10.1021/ja9711627. PMC 1364450

. PMID 16479267. text

. PMID 16479267. text - ↑ R. L. Sass (April 1960). "A neutron diffraction study on the crystal structure of sulfamic acid". Acta Crystallogr. 13 (4): 320–324. doi:10.1107/S0365110X60000789.

- ↑ Nelson, D. L.; Cox, M. M. "Lehninger, Principles of Biochemistry" 3rd Ed. Worth Publishing: New York, 2000. ISBN 1-57259-153-6.

- ↑ IUPAC Gold Book dipolar compounds