Abbasid invasion of Asia Minor (806)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

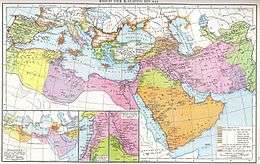

The Abbasid invasion of Asia Minor in 806 was the largest operation ever launched by the Abbasid Caliphate against the Byzantine Empire. The expedition was commanded in person by the Abbasid Caliph Harun al-Rashid (reigned 786–809), who wished to retaliate for the Byzantine successes in the Caliphate's frontier region in the previous year and impress Abbasid might upon the Byzantine emperor, Nikephoros I (r. 802–811). The huge Abbasid army, according to Arab sources numbering more than 135,000 men, raided across Cappadocia unopposed, capturing several towns and fortresses, most notably Herakleia, and forcing Nikephoros to seek peace in exchange for tribute. Following Harun's departure, however, Nikephoros violated the terms of the treaty and reoccupied the frontier forts he had been forced to abandon. Harun's preoccupation with a rebellion in Khurasan, and his death three years later, prohibited a reprisal on a similar scale. Moreover, the Abbasid civil war that began after 809 and the Byzantine preoccupation with the Bulgars contributed to a cessation of large-scale Arab–Byzantine conflict for two decades.

Background

Following the deposition of Byzantine empress Irene of Athens in October 802 and the accession of Nikephoros I in her place, a more violent phase in the long history of the Arab–Byzantine Wars began. Following a series of destructive annual raids across Asia Minor by the Abbasid Caliphate, Irene seems to have secured a truce with the Caliph Harun al-Rashid in 798 in exchange for the annual payment of tribute, repeating the terms agreed for a three-year truce after Harun's first large-scale campaign in 782.[1][2][3] Nikephoros, on the other hand, was more warlike—a Syriac source records that when he learned of Nikephoros's accession, a Byzantine renegade warned the Arab governor of Upper Mesopotamia to "throw away his silk and put on his armour". In addition, he was determined to refill the imperial treasury by, among other measures, ceasing the tribute.[4] Harun retaliated at once, launching a raid under his son al-Qasim in spring 803. Nikephoros could not respond to this, as he faced a large-scale revolt of the Byzantine army of Asia Minor under its commander-in-chief, Bardanes Tourkos. After disposing of Bardanes, Nikephoros assembled his army and marched out to meet a second, larger invasion under the Caliph himself. After Harun raided the frontier region, the two armies confronted one another for two months in central Asia Minor, but it did not come to a battle; Nikephoros and Harun exchanged letters, until the Emperor arranged for a withdrawal and a truce for the remainder of the year in exchange for a one-off payment of tribute.[1][5]

In the next year, 804, an Abbasid force under Ibrahim ibn Jibril crossed the Taurus Mountains into Asia Minor. Nikephoros set out to confront the Arabs, but was surprised and heavily defeated at the Battle of Krasos, where he barely escaped with his own life. Preoccupied with trouble in Khurasan, Harun once more accepted tribute and made peace. An exchange of prisoners was also arranged and took place during the winter at the border of the two empires on the Lamos river in Cilicia: some 3,700 Muslims were exchanged for the Byzantines taken captive in the previous years.[1][3][6] Harun then departed for Khurasan, leaving al-Qasim to watch over the Byzantine frontier. Nikephoros used the opportunity in the spring to rebuild the destroyed walls of the towns of Safsaf, Thebasa, and Ancyra, and that summer, he launched the first Byzantine raid in two decades against the Arab frontier districts (thughur) in Cilicia. The Byzantine army raided the territory surrounding the fortresses of Mopsuestia and Anazarbus and took prisoners as it went. The garrison of Mopsuestia attacked the Byzantine force and recovered most of the prisoners and spoils, but the Byzantines marched on to Tarsus, which had been refortified and repopulated on Harun's orders in 786 to strengthen the Muslim hold on Cilicia. The city fell and the entire garrison was taken captive. At the same time, another Byzantine force raided the Upper Mesopotamian thughur and unsuccessfully besieged the fortress of Melitene, while a Byzantine-instigated rebellion against the local Arab garrison began in Cyprus.[1][7][8]

This sudden resumption of Byzantine offensive activity greatly alarmed Harun. In addition, he received reports that Nikephoros was planning similar attacks for the next year, which this time would aim at the full reoccupation of these frontier territories. As the historian Warren Treadgold writes, if the Byzantines had been successful in this endeavour, "garrisoning Tarsus and Melitene would have partly blocked the main Arab invasion routes across the Taurus into the Byzantine heartland, to the Byzantines' great benefit". On the other hand, Nikephoros was certainly aware of the huge superiority of the Caliphate in men and resources, and it is more likely that he intended this campaign simply as a show of strength and a test of his enemy's resolve.[9]

The campaign

Having settled matters in Khurasan, Harun returned to the west in November 805 and prepared a huge retaliatory expedition for 806, drawing men from Syria, Palestine, Persia, and Egypt. According to al-Tabari, his army numbered 135,000 regular troops and additional volunteers and freebooters. These numbers—and the even more fantastic claims of the Byzantine chronicler Theophanes the Confessor of 300,000 men—are easily the largest ever recorded for the entire Abbasid era and far more than the estimated strength of the entire Byzantine army. Although they are certainly exaggerated, they are nevertheless indicative of the size of the Abbasid force. At the same time, a naval force under his admiral Humayd ibn Ma'yuf al-Hajuri was prepared to raid Cyprus.[10][11][12][13]

The huge invasion army departed Harun's residence of Raqqa in northern Syria on 11 June 806, with the Caliph at its head, allegedly wearing a cap with the inscription "Warrior for the Faith and Pilgrim" (in Arabic, "ghazi, hajj"). The Abbasids crossed Cilicia, where Harun ordered Tarsus to be rebuilt, and entered Byzantine Cappadocia through the Cilician Gates. Harun marched to Tyana, which at the time seems to have been abandoned. There, he began to establish his base of operations, ordering 'Uqbah ibn Ja'far al-Khuza'i to refortify the town and erect a mosque.[14][15][16] Harun's lieutenant Abdallah ibn Malik al-Khuza'i took Sideropalos, from where Harun's cousin Dawud ibn 'Isa ibn Musa with half the Abbasid army, some 70,000 men according to al-Tabari, was sent to devastate Cappadocia. Another of Harun's generals, Sharahil ibn Ma'n ibn Za'ida captured the so-called "Fortress of the Slavs" (Hisn al-Saqalibah) and the recently rebuilt town of Thebasa, while Yazid ibn Makhlad captured the "Fort of the Willow" (al-Safsaf) and Malakopea. Andrasos was captured and Kyzistra was placed under siege, while raiders reached as far as Ancyra, which they did not capture. Harun himself with the other half of his forces went west and captured Herakleia after a month-long siege in August or September. The city was plundered and razed, and its inhabitants enslaved and deported to the Caliphate. At the same time, on Cyprus, Humayd ravaged the island and took some 16,000 Cypriots, including the archbishop, captive to Syria, where they were sold as slaves.[10][17][18]

Poem by Marwan ibn Abi Hafsa in praise of Harun al-Rashid's 806 expedition against Byzantium.[19]

Nikephoros, outnumbered and threatened by the Bulgars in his rear, could not resist the Abbasid onslaught. He campaigned himself at the head of his army and seemingly won a few minor engagements against isolated detachments, but stayed well clear of the main Abbasid forces. In the end, with the harrowing possibility of the Arabs wintering on Byzantine soil in Tyana, he sent three clerics as ambassadors: Michael, the bishop of Synnada, Peter the abbot of the monastery of Goulaion, and Gregory, the steward of the metropolis of Amastris. Harun agreed to terms, which included an annual tribute (30,000 gold nomismata, according to Theophanes, 50,000 according to al-Tabari), but in addition, the Emperor and his son and heir, Staurakios, were to pay a humiliating personal poll-tax (jizya) of three gold coins each to the Caliph (four and two respectively, in Tabari's version), thereby acknowledging themselves as the Caliph's subjects. In addition, Nikephoros promised not to rebuild the dismantled forts. Rashid then recalled his forces from their various sieges and evacuated Byzantine territory.[16][20][21][22]

Aftermath

The agreement of peace terms was followed by a surprisingly friendly exchange between the two rulers, related by al-Tabari: Nikephoros asked Harun to send him a girl from Herakleia, one of the candidate brides for his son Staurakios, and for some perfume. According to Tabari, Harun "ordered the slave girl to be sought out; she was brought back, adorned with finery and installed on a seat in the tent in which he himself was lodging. The slave girl and the tent, together with its contents, vessels and fittings, were handed over to Nikephoros's envoy. He also sent to Nikephoros the perfume which he had requested, and he further sent to him dates, dishes of jellied sweets, raisins and healing drugs." Nikephoros returned the favour by dispatching a horse laden with 50,000 silver coins, 100 satin garments, 200 garments of fine brocade, 12 falcons, four hunting dogs, and three more horses.[23][24] But as soon as the Arabs had withdrawn, the Emperor again restored the frontier forts and thereafter ceased the payment of tribute. Theophanes records that Harun unexpectedly returned and seized Thebasa in retaliation, but this is not corroborated elsewhere.[1][22][24]

The Arabs did launch a series of retaliatory raids in the next year, but the spring raid under Yazid ibn Makhlad al-Hubayri al-Fazari was heavily defeated, with Yazid himself falling in the field. The larger summer raid under Harthama ibn A'yan was met by Nikephoros in person, and after an indecisive battle both sides retreated. The Byzantines raided the region of Marash in return, while in late summer Humayd launched a major naval raid, which pillaged Rhodes and reached as far as the Peloponnese, where it fomented a rebellion among the local Slavs. On his return, however, Humayd lost several ships to a storm, and on the Peloponnese, the Slavic revolt was put down after failing to capture Patras.[25][26][27] The failure of the year's Abbasid efforts was compounded by another revolt in Khurasan, which forced Harun to depart again for the East. The Caliph concluded a new truce, and another prisoner exchange was held at the Lamos in 808. Nikephoros was thus left with his gains, both the restored frontier fortifications and the cessation of tribute, intact.[28]

Impact

Harun's massive expedition achieved remarkably little in material terms. Despite the sack of Herakleia, which is given prominent treatment in Arab sources, no permanent result was achieved, as Nikephoros was quick to violate the terms of the truce. If Harun had taken the advice offered by some of his lieutenants and proceeded further west to sack major cities, he could have inflicted long-lasting damage on Byzantium. As it was, the Caliph was content with a show of force that would intimidate Nikephoros and prevent him from repeating the offensive of 805.a[›] In this regard, the Abbasid campaign was certainly a success: after 806, the Byzantine ruler abandoned whatever expansionist plans he may have had for the eastern border and focused his energy on his fiscal reforms, the recovery of the Balkans, and his wars there against the Bulgars.[29][30] Nikephoros's efforts would end tragically in the disastrous Battle of Pliska in 811, but following Harun's death on 24 March 809, the Caliphate was riven by a civil war between his sons al-Amin (r. 809–813) and al-Ma'mun (r. 813–833), and was not able to exploit the Byzantine reversals. Indeed, the 806 campaign and the ineffectual raids of 807 mark the last major, centrally organized, Abbasid expeditions against Byzantium for over twenty years. Only after the accession of Theophilos (r. 829–842) and his confrontations with al-Ma'mun and al-Mu'tasim (r. 833–842) would large-scale cross-border operations between the two empires resume.[31][32]

The longest-lasting impact of Harun's campaign is found in literature. Among the Arabs, several legends, related by al-Masudi, were associated with it. The Ottoman Turks also placed great importance on Harun's battles with the Byzantines. Influenced by the events of Harun's 782 campaign, Evliya Çelebi has the Caliph besieging Constantinople twice: the first time Harun withdrew, after securing as much land as an oxhide could cover and building a fortress there (an imitation of the tale of Queen Dido) and in the second Harun had Nikephoros hanged from the Hagia Sophia.[33] To commemorate his successful campaign, Harun also built a victory monument about 8 kilometres (5.0 mi) west of Raqqa, his principal residence. Known as Hiraqla in local tradition, apparently after Herakleia, it comprises a square structure with sides 100 metres (330 ft) long, surrounded by a circular wall of some 500 metres (1,600 ft) in diameter, pierced by four gates in the cardinal directions. The main structure, built from stone taken from churches demolished on Harun's orders in 806–807, has four vaulted halls on the ground floor, and ramps leading to an upper storey, which was left incomplete due to Harun's departure for Khurasan and subsequent death.[34]

Notes

^ a: In contrast with their Umayyad predecessors, the Abbasid caliphs pursued a conservative foreign policy. In general terms, they were content with the territorial limits achieved, and whatever external campaigns they waged were retaliatory or preemptive, meant to preserve their frontier and impress Abbasid might upon their neighbours.[35] At the same time, the campaigns against Byzantium in particular were important for domestic consumption. The annual raids were a symbol of the continuing jihad of the early Muslim state and were the only external expeditions where the Caliph or his sons participated in person. They were closely paralleled in official propaganda by the leadership by Abbasid family members of the annual pilgrimage (hajj) to Mecca, highlighting the dynasty's leading role in the religious life of the Muslim community.[36][37]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Brooks 1923, p. 126.

- ↑ Treadgold 1988, p. 113.

- 1 2 Kiapidou 2002, Chapter 1 Archived October 29, 2013, at the Wayback Machine..

- ↑ Treadgold 1988, pp. 127, 130.

- ↑ Treadgold 1988, pp. 131–133.

- ↑ Treadgold 1988, p. 135.

- ↑ Treadgold 1988, pp. 135, 138–139.

- ↑ Bosworth 1989, pp. 261–262.

- ↑ Treadgold 1988, p. 139.

- 1 2 Bosworth 1989, p. 262.

- ↑ Mango & Scott 1997, p. 661.

- ↑ Kennedy 2001, pp. 99, 106.

- ↑ Treadgold 1988, p. 144.

- ↑ Treadgold 1988, pp. 144–145.

- ↑ Bosworth 1989, pp. 262–263.

- 1 2 Kiapidou 2002, Chapter 2 Archived October 29, 2013, at the Wayback Machine..

- ↑ Mango & Scott 1997, pp. 661–662.

- ↑ Treadgold 1988, p. 145.

- ↑ El-Cheikh 2004, p. 90.

- ↑ Bosworth 1989, p. 263

- ↑ Treadgold 1988, pp. 145, 408 (Note #190).

- 1 2 Mango & Scott 1997, p. 662.

- ↑ Bosworth 1989, p. 264.

- 1 2 Treadgold 1988, p. 146.

- ↑ Brooks 1923, p. 127.

- ↑ Treadgold 1988, pp. 147–148

- ↑ Bosworth 1989, pp. 267–268.

- ↑ Treadgold 1988, p. 155.

- ↑ Treadgold 1988, pp. 146, 157ff.

- ↑ Kiapidou 2002, Chapter 3 Archived October 29, 2013, at the Wayback Machine..

- ↑ cf. Brooks 1923, pp. 127ff.

- ↑ cf. Treadgold 1988, pp. 144–152, 157ff.

- ↑ Canard 1926, pp. 103–104.

- ↑ Meinecke 1995, p. 412.

- ↑ El Hibri 2011, p. 302.

- ↑ El Hibri 2011, pp. 278–279.

- ↑ Kennedy 2001, pp. 105–106.

Sources

- Bosworth, C. E., ed. (1989). The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume XXX: The ʿAbbāsid Caliphate in Equilibrium. The Caliphates of Musa al-Hadi and Harun al-Rashid, A.D. 785–809/A.H. 169–193. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-88706-564-3.

- Brooks, E. W. (1923). "Chapter V. (A) The Struggle with the Saracens (717–867)". The Cambridge Medieval History, Vol. IV: The Eastern Roman Empire (717–1453). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 119–138.

- Canard, Marius (1926). "Les expéditions des Arabes contre Constantinople dans l'histoire et dans la légende". Journal Asiatique (in French) (208): 61–121. ISSN 0021-762X.

- El-Cheikh, Nadia Maria (2004). Byzantium Viewed by the Arabs. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard Center of Middle Eastern Studies. ISBN 978-0-932885-30-2.

- El Hibri, Tayeb (2011). "The Empire in Iraq, 763–861". In Robinson, Chase F. The New Cambridge History of Islam, Volume 1: The Formation of the Islamic World, Sixth to Eleventh Centuries. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. pp. 269–304. ISBN 978-0-521-83823-8.

- Kennedy, Hugh N. (2001). The Armies of the Caliphs: Military and Society in the Early Islamic State. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-45853-2.

- Kiapidou, Irini-Sofia (2002). "Campaign of the Arabs in Asia Minor, 806". Encyclopedia of the Hellenic World, Asia Minor. Athens: Foundation of the Hellenic World. Retrieved 22 March 2012.

- Mango, Cyril; Scott, Roger (1997). The Chronicle of Theophanes Confessor. Byzantine and Near Eastern History, AD 284–813. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-822568-7.

- Meinecke, Michael (1995). "al-Raḳḳa". The Encyclopedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume VIII: Ned–Sam. Leiden and New York: BRILL. pp. 410–414. ISBN 90-04-09834-8.

- Treadgold, Warren T. (1988). The Byzantine Revival, 780–842. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-1462-2.