Ainu in Russia

|

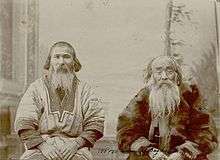

Group of Ainu people in Sakhalin Oblast (1902) | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

|

(109 (Russian Census 2010)[1] 100 to 1,000 (not federally recognized)) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Sakhalin Oblast, Khabarovsk Krai & Kamchatka Krai | |

| Languages | |

| Russian, Ainu languages | |

| Religion | |

| Russian Orthodox & Shamanism (see Ainu mythology) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Ainu of Hokkaido, Kamchadals, Ryukyuan people,[2]Yamato people |

The Ainu in Russia are an indigenous people of Russia located in Sakhalin Oblast, Khabarovsk Krai and Kamchatka Krai. The Russian Ainu people (Айны), also called Kurile (Куриль), Kamchatka's Kurile (Камчатские Куриль / Камчадальские Айны) or Ein (Ейны), can be subdivided into six groups.

Although only around 100 people currently identify themselves as Ainu in Russia (according to the census of 2010), it is believed that at least 1,000 Russian people are of significant Ainu ancestry. The low numbers identifying as Ainu are a result of the refusal by the federal government to recognize the Ainu as a "living" ethnic group. Most of the people who identify themselves as Ainu live in Kamchatka Krai, although the largest number of people who are of Ainu ancestry (without acknowledging it) are found in Sakhalin Oblast.[3]

Subgroups

The Ainu of Russia can be subdivided into six groups, of which three are extinct without even partial descendants.

1. Kamchatka Ainu – known as Kamchatka Kurile in Russian records. Ceased to exist as a separate ethnic group after their defeat in 1706 by the Russians and the smallpox epidemics which followed it. Individuals were assimilated into the Kurile and Kamchadal ethnic groups. Last recorded in the 18th century by Russian explorers.[4]

2. Northern Kuril Ainu – also known as Kurile in Russian records. Were under Russian rule till 1875. First came under Japanese rule after the Treaty of Saint Petersburg (1875). Major population was on the island of Shumshu, with a few others in islands like Paramushir. Altogether they numbered 221 in 1860. They had Russian names, spoke Russian fluently and were Russian Orthodox in religion. As the islands were given to the Japanese, more than a hundred Ainu fled to Kamchatka along with their Russian employers (where they were assimilated into the Kamchadal population).[5][6] Those who remained under Japanese rule became extinct after the World War 2. Numbers close to 100 people currently in Ust-Bolsheretsky District.

3. Southern Kuril Ainu – Numbered almost 2,000 people (mainly in Kunashir, Iturup and Urup) during the 18th century. In 1884, their population had decreased to 500. Around 50 individuals (mostly multiracial) who remained in 1941 were evacuated to Hokkaido by the Japanese soon after WW2.[5] The last of the tribe in Japan, Tanaka Kinu died in Hokkaido in 1973.[7] Only 6 members (all from Nakamura clan) survive in Russia.

4. Amur Valley Ainu – a few individuals married to ethnic Russians and ethnic Ulchi reported by Bronisław Piłsudski in the early 20th century.[8] Only 26 pure-blooded individuals were recorded during the 1926 Russian Census in Nikolaevski Okrug (present day Николаевский район Nikolaevskij Region/District).[9] Probably assimilated into the Slavic rural population. Although no one identifies as Ainu nowadays in Khabarovsk Krai, there are a large number of ethnic Ulch with partial Ainu ancestry.[10][11]

5. North Sakhalin Ainu - Only 5 pure blooded individuals were recorded during the 1926 Russian Census in Northern Sakhalin. Most of the Sakhalin Ainu (mainly from coastal areas) were relocated to Hokkaido in 1875 by Japan. The few remained (mainly from remote interior) were mostly married to Russians as can be seen from the works of Bronisław Piłsudski.[12] Extinct as a tribe, but may be possible to find isolated individuals of distant Ainu ancestry.

6. Southern Sakhalin Ainu – Japan evacuated almost all the Ainu to Hokkaido after the Second World War. Isolated individuals might have remained in Sakhalin.[13] In 1949, there were about 100 Ainu living in Russian Sakhalin.[5] Ainu of Sakhalin were under extreme pressure from the Soviet authorities and after 1945, children were not allowed to use "Ainu" as their nationality. The last three full blooded individuals died during the 1980s. Only people of mixed ethnic origin (Russian-Ainu, Japanese-Ainu and Gilyak-Ainu) remain now. They number several hundred, but very few acknowledge their Ainu ancestry.

History

The Kamchatka Ainu first came into contact with Russian fur traders by the end of the 17th century. Contact with the Amur Ainu and North Kuril Ainu were established during the 18th century. The Ainu thought the Russians, who differed from their Mongoloid Japanese enemies were their friends and by mid-18th century more than 1,500 Ainu had accepted Russian citizenship. Even the Japanese failed to differentiate between the Ainu and Russian, because of physical similarities (white skin and Caucasoid facial features).

When the Japanese first came into contact with the Russians, they called them Red Ainu (blonde haired Ainu). Only during the beginning of the 19th century did the Japanese learn that the Russians are a different group altogether. The Russians however reported the Ainu as "hairy", "swarthy", and with dark eyes and hair. Early Russian explorers reported that the Ainu looked like bearded Russian peasants (with swarthy skin) or like the Roma people.

The Ainu (especially those in the Kurils) supported the Russians over the Japanese in conflicts of the 19th century. However, after their defeat during the Russo-Japanese War of 1905, the Russians abandoned their allies and left them to their fate. Hundreds of Ainu were executed and their families were forcibly relocated to Hokkaido by the Japanese. As a result, the Russians failed to win over the Ainu during World War II. Only a few Ainu chose to remain in Russia after the war. More than 90% accepted repatriation to Japan.

Resettlement in Kamchatka

As a result of the Treaty of St. Petersburg, the Kuril islands were handed over to the Japanese, along with the Ainu inhabitants. A total of 83 North Kuril Ainu arrived in Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky on September 18, 1877 after they decided to remain under Russian rule. They refused the offer by Russian officials to move to new reservations in the Commander Islands. Finally a deal was reached in 1881 and the Ainu decided to settle in the village of Yavin. In March 1881 the group left Petropavlovsk and started the journey towards Yavin by foot. Four months later, they arrived at their new homes. Another village, Golygino was founded later. Nine more Ainu arrived from Japan in 1884. According to the 1897 Census of Russia, Golygino had a population of 57 (all Ainu) and Yavin had a population of 39 (33 Ainu & 6 Russian).[14] Under Soviet rule, both the villages were liquidated and residents were moved to the Russian dominated Zaporozhye rural settlement in Ust-Bolsheretsky Raion.[15] As a result of intermarriage, the three ethnic groups assimilated to form the Kamchadal community.

During the Tsarist times, the Ainu living in Russia were forbidden from identifying themselves as such, as the Imperial Japanese officials had claimed that all the regions inhabited by the Ainu in the past or present were part of Japan. The terms "Kurile", "Kamchatka Kurile", and similar terms were used to identify the ethnic group. During the Soviet times, people with Ainu surnames were sent to gulags and labor camps, as they were often mistaken for Japanese. As a result, a large number of Ainu changed their surnames to Slavic ones.

On 7 February 1953, K. Omelchenko, the minister of the protection of military and state secrets in the USSR banned the press from publishing any data on the Ainu living in the USSR. This order was revoked after two decades.[16]

Recent History

The North Kuril Ainu of Zaporozhye are currently the largest Ainu subgroup in Russia. The Nakamura clan (South Kuril Ainu from the paternal side) are the smallest and numbers just 6 people residing in Petropavlovsk. On Sakhalin island, there are a few dozen people who identify themselves as Sakhalin Ainu, but many more with partial Ainu ancestry do not acknowledge it. Most of the 888 Japanese people living in Russia (2010 Census) are of mixed Japanese-Ainu ancestry, although they do not acknowledge it (full Japanese ancestry gives them the right of visa-free entry to Japan).[17] Similarly, no one identifies themselves as Amur Valley Ainu, although people with partial descent can be found in Khabarovsk. It is believed that no living descendants of the Kamchatka Ainu are alive.

In 1979, the USSR removed the term "Ainu" from the list of living ethnic groups of Russia, an act by which the government proclaimed that the Ainu as an ethnic group was extinct in its territory. According to the 2002 Russian Federation census, no responders gave the ethnonym Ainu in boxes 7 or 9.2 in the K-1 form of the census.[18][19][20]

The Ainu have emphasized that they were the natives of the Kuril islands and that the Japanese and Russians were both invaders.[21]

In 2004, the small Ainu community living in Kamchatka Krai wrote a letter to Vladimir Putin, urging him to reconsider any move to award the Southern Kuril islands to Japan. In the letter they blamed both the Japanese, the Tsarist Russians and the Soviets for crimes against the Ainu such as killings and assimilation, and they also urged him to recognize the Japanese genocide against the Ainu people, which was turned down by Putin.[22] According to the community, their tragedy is only comparable in scale and intensity with the genocide faced by the indigenous people of the Americas.

During the 2010 Census of Russia, close to 100 people tried to register themselves as ethnic Ainu in the village, but the governing council of Kamchatka Krai rejected their claims and enrolled them as ethnic Kamchadal.[23][24] In 2011, the leader of the Ainu community in Kamchatka, Alexei Vladimirovich Nakamura requested Vladimir Ilyukhin (Governor of Kamchatka) and Boris Nevzorov (Chairman of state Duma) to include the Ainu in the central list of Indigenous small-numbered peoples of the North, Siberia and the Far East. This request was also turned down.[25]

Ethnic Ainu living in Sakhalin Oblast and Khabarovsk Krai are not organized politically. According to Alexei Nakamura, as of 2012, there are only 205 Ainu living in Russia (up from just 12 people who self-identified as Ainu in 2008) and they, along with the Kurile Kamchadals (Itelmen of Kuril Islands), are fighting for official recognition.[26][27] Since the Ainu are not recognized in the official list of the peoples living in Russia, they are counted as people without nationality or as ethnic Russian or Kamchadal.[28]

As of 2012, Both the Kurile Ainu and Kurile Kamchadal ethnic groups are devoid of the fishing and hunting rights, which the Russian government grants to the indigenous tribal communities of the far north.[3][29]

Recently the Ainu formed a Russian Association of the Far-Eastern Ainu (RADA) under Rechkabo Kakukhoningen (Boris Yaravoy).[30]

Demographics

According to the Russian Census (2010), a total of 109 Ainu live in Russia. Of this, 94 lived in Kamchatka Krai, 4 in Primorye, 3 in Sakhalin, 1 in Khabarovsk, 4 in Moscow, 1 in St.Petersburg, 1 in Sverdlovsk, and 1 in Rostov. The real population is believed to be much higher, as hundreds of Ainu in Sakhalin refused to identify themselves as such.[31]

Ainu of Sakhalin

During the Tsarist times, the Ainu living in Russia were forbidden from identifying themselves as such, as the Imperial Japanese officials had claimed that all the regions inhabited by the Ainu in the past or present, are a part of Japan. The terms "Kurile", "Kamchatka Kurile".etc. were used to identify the ethnic group. During the Soviet times, people with Ainu surnames were sent to gulags and labor camps, as they were often mistaken for the Japanese. As a result, large number of Ainu changed their surnames to Slavic ones. To eradicate the Ainu identity, the Soviet authorities removed the ethnic group from the list of nationalities which can be mentioned in the passport. Due to this, children born after 1945 were not able to identify themselves as Ainu.

After the World War 2, most of the Ainu living in Sakhalin were deported to Japan. Out of the 1,159 Ainu, only around 100 remained in Russia. Of those who remained, only the elderly were full blooded Ainu. Others were either mixed race or married to ethnic Russians. The last of the Ainu households disappeared in the late 1960s, when Yamanaka Kitaro committed suicide after the death of his wife. The couple was childless.[32]

Ainu of Ust-Bolsheretsky

Out of a total of 826 people living in the village of Zaporozhye in Ust-Bolsheretsky, more than 100 people claimed during the 2010 Census that they are Ainu. They are former residents of the liquidated villages Yavin and Golygino. The number of people with Ainu ancestry is estimated to be many times this amount, but in general, there is reluctance from the individuals themselves and from the census takers to record the nationality as "Ainu" (although not on a scale which is seen in Sakhalin). The majority of the population in Zaporozhye refers themselves as either Kamchadal (a term used for mixed race individuals with heavy Slavic admixture) or Russian, rather than identifying with either of the two native ethnic groups (Ainu and Itelmen). Although identifying as Itelmen can give additional benefits (hunting and fishing rights), the residents seems to be wary about ethnic polarization and response from full-blooded Russian neighbors. Identifying as Ainu is not beneficial in any way. As an unrecognized nation, the Ainu are not eligible for either fishing or hunting quotas.

Families who are the descended from Kuril Ainu include Butin (Бутины), Storozhev (Сторожевы), Ignatiev (Игнатьевы), Merlin (Мерлины), Konev (Коневы), Lukaszewski (Лукашевские), and Novograblin (Новограбленные).

Ainu of Clan Nakamura

Unlike the other Ainu clans currently living in Russia, there is considerable doubt whether the Nakamura clan of Kamchatka should be identified as Northern Kurils Ainu, Southern Kurils Ainu or as Kamchatka Ainu. This is due to the fact that the clan originally immigrated to Kamchatka from Kunashir in 1789. The Ainu of Kunashir are South Kurils Ainu. They settled down near Kurile Lake, which was inhabited by the Kamchatka Ainu and North Kuril Ainu. In 1929, the Ainu of Kurile Lake fled to the island of Paramushir after an armed conflict with the Soviet authorities. At that time, Paramushir was under Japanese rule. During the Invasion of the Kuril Islands, Akira Nakamura (b. 1897) was captured by the Soviet army and his elder son Takeshi Nakamura (1925–1945) was killed in the battle. Akira's only surviving son, Keizo (b. 1927) was taken prisoner and joined the Soviet Army after his capture. After the war, Keizo went to Korsakov to work in the local harbor. In 1963, he married Tamara Pykhteeva, a member of the Sakhalin Ainu tribe. Their only child, Alexei was born in 1964. The descendants of Tamara and Alexei are found in Kamchatka and Sakhalin.

The last known deportation of Ainu to Japan occurred in 1982, when Keizo Nakamura, a full blooded Southern Kurils Ainu was deported to Hokkaido after serving 15 years hard labor in the province of Magadan. His wife, Tamara Timofeevna Pykhteeva was of mixed Sakhalin Ainu and Gilyak ancestry. After the arrest of Keizo in 1967, Tamara and her son Alexei Nakamura were expelled from Kamchatka Krai and sent to the island of Sakhalin, to live in the city of Tomari.

Ainu of Komandorski Islands

In 1877, the Badaev (Бадаев) family split from the rest of Northern Kuril Ainu and decided to settle in the Commander Islands, along with the Aleut. They were assimilated by the Aleut and currently identify themselves as Aleut. Two of the families residing there are believed to be of partial Ainu ancestry - the Badaevs and the Kuznetsovs.[33]

Commander Islands was originally designated as a refuge for the Aleut people (from Atka, Attu, Fox, Andreanof.etc.), who were forced to flee Alaska after Russia sold it to the US. In 1827, on Bering Island lived 110 people (Of which 93 either Aleut or Aleut-Russian creole). Since the Northern Kuril Ainu were also having similar problems, the Tsar hoped to resettle them near the Aleut. But the Ainu were skeptical of the offer and rejected it, as they wanted to stay in Kamchatka mainland, whose geography was familiar to them. Only one Ainu family moved to the island, and were joined by ethnic Russians, Kamchadals, Itelmen, Kadyaktsy (Kodiak Island Eskimo), Creoles (mixed origin people or Metis), Komi-Zyrians and Roma.

By 1879, the island was home to a total of 168 Aleut and 332 Creole, plus around 50 to 60 people from other nationalities including the Ainu and Russian. All the Creole spoke the Aleut language, as it was the language of their mothers. The Ainu, along with other minorities were quickly assimilated by the Aleut within a few decades.

Federal recognition

According to the Census authority of Russian Federation, the Ainu are extinct as an ethnic group in Russia. Those who identify as Ainu, neither speak the Ainu language, nor practice any aspect of the traditional Ainu culture. In social behavior and customs, they are almost identical with the Old Russian settlers of Kamchatka and therefore the benefits which are given to the Itelmen cannot be given to the Ainu of Kamchatka.

The Ainu language is extinct as a spoken language in Russia. The Bolsheretsky Kurile stopped using the language as early as the beginning of the 20th century. Only 3 fluent speakers remained in Sakhalin as of 1979, and the language was extinct by the 1980s there. Although Keizo Nakamura was a fluent speaker of Kurile Ainu and translated several documents from the language to Russian for the NKVD, he didn't pass on the language to his son. (Take Asai, the last speaker of Sakhalin Ainu, died in Japan in 1994.[34])

References

- ↑ http://www.gks.ru/free_doc/new_site/perepis2010/croc/Documents/Materials/pril3_dok2.xlsx

- ↑

- 1 2 http://english.ruvr.ru/radio_broadcast/2249159/49638669.html

- ↑ Shibatani, Masayoshi (1990). The languages of Japan. Cambridge University Press via Google Books. p. 3.

- 1 2 3 Wurm, Stephen Adolphe; Mühlhäusler, Peter; Tryon, Darrell T. (1996). Atlas of languages of intercultural communication in the Pacific, Asia and the Americas. Walter de Gruyter via Google Books. p. 1010.

- ↑ Minichiello, Sharon (1998). Japan's competing modernities: issues in culture and democracy, 1900-1930. University of Hawaii Press via Google Books. p. 163.

- ↑ http://uwspace.uwaterloo.ca/bitstream/10012/2765/1/Scott%20Harrison_GSO_Thesis.pdf

- ↑ Piłsudski, Bronisław; Majewicz, Alfred F. (2004). The collected works of Bronisław Piłsudski Volume 3. Walter de Gruyter via Google Books. p. 816.

- ↑ http://demoscope.ru/weekly/ssp/rus_nac_26.php?reg=1410

- ↑ Shaman: an international journal for Shamanistic research, Volumes 4-5 p.155

- ↑ Piłsudski, Bronisław; Majewicz, Alfred F. (2004). The collected works of Bronisław Piłsudski Volume 3. Walter de Gruyter via Google Books. p. 37.

- ↑ Howell, David L. (2005). Geographies of identity in nineteenth-century Japan. University of California Press via Google Books. p. 187.

- ↑ http://demoscope.ru/weekly/ssp/rus_nac_26.php?reg=1420

- ↑ http://ansipra.npolar.no/russian/Items/Japan-3%20Ru.html

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IcIErWxe16k

- ↑ http://kamchatka-etno.ru/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=85&Itemid=95

- ↑ http://www.5-tv.ru/news/37800/

- ↑ http://www.perepis2002.ru/ct/doc/English/4-2.xls

- ↑ http://www.perepis2002.ru/ct/doc/English/4-3.xls

- ↑ http://www.perepis2002.ru/index.html?id=87

- ↑ McCarthy, Terry (September 22, 1992). "Ainu people lay ancient claim to Kurile Islands: The hunters and fishers who lost their land to the Russians and Japanese are gaining the confidence to demand their rights". The Independent.

- ↑ http://kamtime.ru/old/archive/08_12_2004/13.shtml

- ↑ http://www.kamchatka-etno.ru/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=85&Itemid=95

- ↑ http://pk.russiaregionpress.ru/archives/4889

- ↑ http://severdv.ru/news/show/?id=52022&r=27&p=41

- ↑ http://nazaccent.ru/interview/13/

- ↑ http://www.segodnia.ru/content/105359

- ↑ http://www.rg.ru/2008/04/03/reg-dvostok/ainu.html

- ↑ http://www.indigenous.ru/modules.php?name=News&file=article&sid=894

- ↑ http://www.eurasiareview.com/10042011-russias-ainu-community-makes-its-existence-known-analysis/

- ↑ http://rusk.ru/st.php?idar=44728

- ↑ http://www.agesmystery.ru/node/630

- ↑ http://www.svevlad.org.rs/knjige_files/ajni_prjamcuk.html

- ↑ Piłsudski, Bronisław; Alfred F. Majewicz (2004). The Collected Works of Bronisław Piłsudski. Trends in Linguistics Series. 3. Walter de Gruyter. p. 600. ISBN 9783110176148. Retrieved 2012-05-22.