Amputation

| Amputation | |

|---|---|

|

J. McKnight, who lost his limbs in a railway accident in 1865, was the second recorded survivor of a simultaneous triple amputation. | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | emergency medicine |

| ICD-10 | T14.7 |

| MeSH | D000673 |

Amputation is the removal of a limb by trauma, medical illness, or surgery. As a surgical measure, it is used to control pain or a disease process in the affected limb, such as malignancy or gangrene. In some cases, it is carried out on individuals as a preventative surgery for such problems. A special case is that of congenital amputation, a congenital disorder, where fetal limbs have been cut off by constrictive bands. In some countries, amputation of the hands, feet or other body parts is or was used as a form of punishment for people who committed crimes. Amputation has also been used as a tactic in war and acts of terrorism; it may also occur as a war injury. In some cultures and religions, minor amputations or mutilations are considered a ritual accomplishment. Unlike some non-mammalian animals (such as lizards that shed their tails, salamanders that can regrow many missing body parts, and hydras, flatworms, and starfish that can regrow entire bodies from small fragments), once removed, human extremities do not grow back, unlike portions of some organs, such as the liver. A transplant or a prosthesis are the only options for recovering the loss.

In the US, the majority of new amputations occur due to complications of the vascular system (the blood vessels), especially from diabetes. Between 1988 and 1996, there were an average of 133,735 hospital discharges for amputation per year in the US.[1]

History

The word amputation is derived from the Latin amputare, "to cut away", from ambi- ("about", "around") and putare ("to prune"). The Latin word has never been recorded in a surgical context, being reserved to indicate punishment for criminals. The English word "amputation" was first applied to surgery in the 17th century, possibly first in Peter Lowe's A discourse of the Whole Art of Chirurgerie (published in either 1597 or 1612); his work was derived from 16th-century French texts and early English writers also used the words "extirpation" (16th-century French texts tended to use extirper), "disarticulation", and "dismemberment" (from the Old French desmembrer and a more common term before the 17th century for limb loss or removal), or simply "cutting", but by the end of the 17th century "amputation" had come to dominate as the accepted medical term.

Types

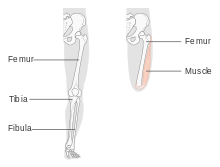

Leg amputations

Leg amputations can be divided into 2 broad categories:

- Minor amputations:

- Major amputations:

- Below-knee amputation, abbreviated as BKA. Intentionally performed surgical below-knee amputation can be performed by transtibial techniques such as Burgess and Kingsley Robinson.

- knee disarticulation (Gritti or Gritti-Stokes)

- above-knee amputation (transfemoral)

- Van-ness rotation/rotationplasty (foot being turned around and reattached to allow the ankle joint to be used as a knee)

- hip disarticulation

- hemipelvectomy/hindquarter amputation

Arm amputations

- amputation of digits

- metacarpal amputation

- wrist disarticulation

- forearm amputation (transradial)

- elbow disarticulation

- above-elbow amputation (transhumeral)

- shoulder disarticulation and forequarter amputation

- Krukenberg procedure

Other amputations

- Face:

- amputation of the ears

- amputation of the nose (rhinotomy)

- amputation of the tongue (glossectomy).

- amputation of the eyes (blinding). Many of these facial disfigurings were and still are done in some parts of the world as punishment for some crimes, and as individual shame and population terror practices.

- amputation of the teeth. Removal of teeth, mainly incisors, is or was practiced by some cultures for ritual purposes (for instance in the Iberomaurusian culture of Neolithic North Africa).

- Breasts:

- amputation of the breasts (mastectomy).

- Genitals amputation

- amputation of the testicles (castration).

- amputation of the penis (penectomy).

- amputation of the foreskin (circumcision).

- amputation of the clitoris (clitoridectomy).

Hemicorporectomy, or amputation at the waist, and decapitation, or amputation at the neck, are the most radical amputations.

Genital modification and mutilation may involve amputating tissue, although not necessarily as a result of injury or disease.

Self-amputation

In some rare cases when a person has become trapped in a deserted place, with no means of communication or hope of rescue, the victim has amputated his or her own limb:

- In 2007, 66-year-old Al Hill amputated his leg below the knee using his pocketknife after the leg got stuck beneath a fallen tree he was cutting in California.[3]

- In 2007, Sampson Parker, a South Carolina farmer, cut off his own arm after it became stuck in a corn harvester.[4][5]

- In 2003, 27-year-old Aron Ralston amputated his forearm using his pocketknife and breaking and tearing the two bones, after the arm got stuck under a boulder when hiking in Utah.[6] He documented the story of his ordeal in his book Between a Rock and a Hard Place which was turned into the movie 127 Hours.

- In 2003, an Australian coal miner amputated his own arm with a Stanley knife after it became trapped when the front-end loader he was driving overturned three kilometers underground. The amputation proved to be unnecessary as emergency services arrived and recovered the trapped arm, but were unable to reattach it.[7]

Rarely, self-amputation is performed for criminal or political purposes.

- On March 7, 1998, Daniel Rudolph, the elder brother of the 1996 Olympics bomber Eric Robert Rudolph, videotaped himself cutting off one of his own hands with an electric saw to "send a message to the FBI and the media."[8]

Body integrity identity disorder is a psychological condition in which an individual feels compelled to remove one or more of their body parts, usually a limb. In some cases, that individual may take drastic measures to remove the offending appendages, either by causing irreparable damage to the limb so that medical intervention cannot save the limb, or by causing the limb to be severed.

Causes

Circulatory disorders

- Diabetic foot infection or gangrene (the most frequent reason for infection-related amputations)

- Sepsis with peripheral necrosis

Neoplasm

- Cancerous bone or soft tissue tumors (e.g. osteosarcoma, chondrosaroma, fibrosarcoma, epithelioid sarcoma, Ewing's sarcoma, synovial sarcoma, sacrococcygeal teratoma, liposarcoma)

- Melanoma

Trauma

- Severe limb injuries in which the limb cannot be saved or efforts to save the limb fail.

- Traumatic amputation (an unexpected amputation that occurs at the scene of an accident, where the limb is partially or entirely severed as a direct result of the accident, for example a finger that is severed from the blade of a table saw).

- Amputation in utero (Amniotic band)

Deformities

- Deformities of digits and/or limbs (e.g., proximal femoral focal deficiency)

- Extra digits and/or limbs (e.g., polydactyly)

Infection

- Bone infection (osteomyelitis)

- Diabetes

- Frostbite

Athletic performance

- Sometimes professional athletes may choose to have a non-essential digit amputated to relieve chronic pain and impaired performance. Australian Rules footballer Daniel Chick elected to have his left ring finger amputated as chronic pain and injury was limiting his performance.[9] Rugby union player Jone Tawake also had a finger removed.[10] National Football League safety Ronnie Lott had the tip of his little finger removed after it was damaged in the 1985 NFL season.

Legal punishment

- Amputation is used as a legal punishment in a number of countries, among them Iran, Yemen, United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, and Islamic regions of Nigeria.[11]

Surgical amputation

Method

The first step is ligating the supplying artery and vein, to prevent hemorrhage (bleeding). The muscles are transected, and finally the bone is sawed through with an oscillating saw. Sharp and rough edges of the bone(s) are filed down, skin and muscle flaps are then transposed over the stump, occasionally with the insertion of elements to attach a prosthesis.

Traumatic amputation

Traumatic amputation is the partial or total avulsion of a part of a body during a serious accident, like traffic, labor, or combat.[12][13][14]

Traumatic amputation of a human limb, either partial or total, creates the immediate danger of death from blood loss.[15]

Orthopedic surgeons often assess the severity of different injuries using the Mangled Extremity Severity Score. Given different clinical and situational factors, they can predict the likelihood of amputation. This is especially useful for emergency physicians to quickly evaluate patients and decide on consultations.[16]

Causes

Traumatic amputation is uncommon in humans (1 per 20,804 population per year). Loss of limb usually happens immediately during the accident, but sometimes a few days later after medical complications. Statistically the most common causes of traumatic amputations are:[13]

- Traffic accidents (cars, motorcycles, bicycles, trains, etc.)

- Labor accidents (equipment, instruments, cylinders, chainsaws, press machines, meat machines, wood machines, etc.)

- Agricultural accidents, with machines and mower equipment

- Electric shock hazards

- Guns, weapons, explosives, dynamite, bombs, fireworks, etc.

- Violent rupture of ship rope or industry wire rope

- Ring traction (ring amputation, de-gloving injuries)

- Building doors and car doors

- Gas cylinder explosions[17]

- Other rare accidents[13]

Treatment

The development of the science of microsurgery over last 40 years has provided several treatment options for a traumatic amputation, depending on the patient's specific trauma and clinical situation:

- 1st choice: Surgical amputation - break - prosthesis

- 2nd choice: Surgical amputation - transplantation of other tissue - plastic reconstruction.

- 3rd choice: Replantation - reconnection - revascularisation of amputated limb, by microscope (after 1969)

- 4th choice: Transplantation of cadaveric hand (after 2000),[13][18]

Epidemiology

- In the United States in 1999, there were 14,420 non-fatal traumatic amputations according to the American Statistical Association. Of these, 4,435 occurred as a result of traffic and transportation accidents and 9,985 were due to labor accidents. Of all traumatic amputations, the distribution percentage is 30.75% for traffic accidents and 69.24% for labor accidents.[19]

- The population of the United States in 1999 was about 300,000,000, so the conclusion is that there is one amputation per 20,804 persons per year. In the group of labor amputations, 53% occurred in laborers and technicians, 30% in production and service workers, 16% in silviculture and fishery workers.[19]

- A study found that in 2010, 22.8% of patients undergoing amputation of a lower extremity in the United States were readmitted to the hospital within 30 days.[20]

Prevention

Amputations are usually traumatic experiences. They can reduce the quality of life for patients in addition to being expensive. In the USA, a typical prosthetic limb costs in the range of $10,000–15,000 according to the American Diabetic Association. In some populations, preventing amputations is a critical task.

Methods in preventing amputation, limb-sparing techniques, depend on the problems that might cause amputations to be necessary. Chronic infections, often caused by diabetes or decubitus ulcers in bedridden patients, are common causes of infections that lead to gangrene, which would then necessitate amputation.

There are two key challenges: first, many patients have impaired circulation in their extremities, and second, they have difficulty curing infections in limbs with poor vasculation (blood circulation).

Crush injuries where there is extensive tissue damage and poor circulation also benefit from hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT). The high level of oxygenation and revascularization speed up recovery times and prevent infections.

A study found that the patented method called Circulator Boot achieved significant results in prevention of amputation in patients with diabetes and arterioscleorosis.[21][22] Another study found it also effective for healing limb ulcers caused by peripheral vascular disease.[23] The boot checks the heart rhythm and compresses the limb between heartbeats; the compression helps cure the wounds in the walls of veins and arteries, and helps to push the blood back to the heart.[24]

For victims of trauma, advances in microsurgery in the 1970s have made replantations of severed body parts possible.

The establishment of laws, rules and guidelines, and employment of modern equipment help protect people from traumatic amputations.[15]

Prognosis

The individual may experience psychological trauma and emotional discomfort. The stump will remain an area of reduced mechanical stability. Limb loss can present significant or even drastic practical limitations.

A large proportion of amputees (50–80%) experience the phenomenon of phantom limbs;[25] they feel body parts that are no longer there. These limbs can itch, ache, burn, feel tense, dry or wet, locked in or trapped or they can feel as if they are moving. Some scientists believe it has to do with a kind of neural map that the brain has of the body, which sends information to the rest of the brain about limbs regardless of their existence. Phantom sensations and phantom pain may also occur after the removal of body parts other than the limbs, e.g. after amputation of the breast, extraction of a tooth (phantom tooth pain) or removal of an eye (phantom eye syndrome).

A similar phenomenon is unexplained sensation in a body part unrelated to the amputated limb. It has been hypothesized that the portion of the brain responsible for processing stimulation from amputated limbs, being deprived of input, expands into the surrounding brain, (Phantoms in the Brain: V.S. Ramachandran and Sandra Blakeslee) such that an individual who has had an arm amputated will experience unexplained pressure or movement on his face or head.

In many cases,the phantom limb aids in adaptation to a prosthesis, as it permits the person to experience proprioception of the prosthetic limb. To support improved resistance or usability, comfort or healing, some type of stump socks may be worn instead of or as part of wearing a prosthesis.

Another side effect can be heterotopic ossification, especially when a bone injury is combined with a head injury. The brain signals the bone to grow instead of scar tissue to form, and nodules and other growth can interfere with prosthetics and sometimes require further operations. This type of injury has been especially common among soldiers wounded by improvised explosive devices in the Iraq war.[26]

Due to technologic advances in prosthetics, many amputees live active lives with little restriction. Organizations such as the Challenged Athletes Foundation have been developed to give amputees the opportunity to be involved in athletics and adaptive sports such as Amputee Soccer.

Gallery

-

A woodcut engraving in Feldbuch der Wundarzney (1517) by Hans von Gersdorff, showing how to remove a leg.

-

An amputee beggar, by Jacques Callot, 1622

-

In a 1786 James Gillray caricature, the plentiful money bags handed to King George III are contrasted with the beggar whose legs and arms were amputated, in the left corner

-

Alfred A. Stratton, an American Civil War veteran and double amputee

-

Amputee veterans of World War II in Germany, 1946

-

John McFall, who has an above-knee leg amputation, and uses a prosthetic leg, is a sprinter and winner of a gold medal at the 2007 Paralympic World Cup

-

An American soldier who was wounded by a rocket-propelled grenade in Iraq

-

Aron Ralston, an outdoorsman who was forced to amputate his own right arm with a multi-tool after having it trapped between a boulder and a canyon wall.

-

Team Zaryen amputee soccer

-

South African sprint runner and convicted murderer Oscar Pistorius

-

An amputee of the right leg photographed in the Historic Center of Quito in 2013.

-

Lisa Bufano, dancer and performance artist

See also

References

- ↑ "Amputee Coalition Factsheet". Amputee-coalition.org. 2012-07-23. Retrieved 2013-04-22.

- ↑ Pinzur, M.S.; Stuck, RM; Sage, R; Hunt, N; Rabinovich, Z (September 2003). "Syme ankle disarticulation in patients with diabetes". J Bone Joint Surg Am. 85–A (9): 1667–1672. PMID 12954823.

- ↑ Man Pinned Under Tree Amputates His Leg Archived August 8, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Farmer Cuts Off Right Arm With Pocket Knife to Save Life". Foxnews.com. Retrieved 2013-04-22.

- ↑ "Farmer Describes Cutting Off Own Arm". Wyff4.com. 2007-11-24. Retrieved 2013-04-22.

- ↑ Kennedy, J. Michael (May 9, 2003). "CMU grad describes cutting off his arm to save his life". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Archived from the original on 2010-11-18. Retrieved 2008-05-07.

- ↑ "Arm trapped, and fearing fire, tough miner knew what to do". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 2010-11-18.

- ↑ "Bombing suspect's brother cuts hand off with saw". March 9, 1998. Archived from the original on 2010-11-18.

- ↑ RTE: Aussie Rules star has finger removed Archived August 15, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Australian Rugby Union (2006-10-17). "Tawake undergoes surgery to remove finger". SportsAustralia.com. Retrieved 2013-04-22.

- ↑ United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (2008-01-07). "UNHCR article on amputation as a punishment in Iran". Unhcr.org. Retrieved 2013-04-22.

- ↑ Current Surgical Diagnosis and Treatment: "Amputations", editions Lange, USA, 2009

- 1 2 3 4 Harry Gouvas: "Accidents and Massive Disasters", editions of Greek Red Cross, 2000

- ↑ Neil Watson: "Hand Injuries and Infections" Cower Medical Publishing, London, New York, 1996, ISBN 0-906923-80-8

- 1 2 Harry Gouvas: "Accidents and massive Disasters", Editions of Greek Red Cross, 2000

- ↑ Johansen K, Daines M, Howey T, Helfet D, Hansen ST Jr (1990). "Objective criteria accurately predict amputation following lower extremity trauma.". J Trauma. 30 (5): 568–72; discussion 572–3. doi:10.1097/00005373-199005000-00007. PMID 2342140.

- ↑ "Scuba Tanks as Lethal Weapons". undercurrent.org. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- ↑ Neil Watson: "Hand Injuries and Infections"Cower Medical Publishing,ISBN 0-906923-80-8

- 1 2 American Statistical Association: Amputations in USA, 2000

- ↑ Weiss AJ, Elixhauser A, Steiner C. Readmissions to U.S. Hospitals by Procedure, 2010. HCUP Statistical Brief #154. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. April 2013.

- ↑ Richard S. Dillon (May 1997). "Fifteen Years of Experience in Treating 2177 Episodes of Foot and Leg Lessions with the Circulator Boot". Angiology. 48 (5 (part 2)): S17–S34. doi:10.1177/000331979704800503. Archived from the original on 2010-11-18.

- ↑ Richard S. Dillon; Yai, H; Maruhashi, J (May 1997). "FPatient Assessment and Examples of a Method of Treatment. Use of the Circulator Boot in Peripherical Vascular Disease". Angiology. 48 (5 (part 2)): S35–S58. doi:10.1177/000331979704800504. PMID 9158380. Archived from the original on 2010-11-18.

- ↑ Vella A, Carlson LA, Blier B, Felty C, Kuiper JD, Rooke TW (2000). "Circulator boot therapy alters the natural history of ischemic limb ulceration.". Vasc. Med. 5 (1): 21–25. doi:10.1191/135886300671427847. PMID 10737152.

- ↑ Circulator Boot at Mayo Clinic 1:08–1:32

- ↑ Heidi Schultz (January 2005). "The Science of Things". National Geographic Magazine. Archived from the original on September 6, 2008.

- ↑ Ryan, Joan (March 25, 2006). "War without end / Damaged soldiers start their agonizing recoveries". The San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on 2010-11-18.

Further reading

- Miller, Brian Craig. Empty Sleeves: Amputation in the Civil War South (University of Georgia Press, 2015). xviii, 257 pp.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Amputations. |

- Amputation from Cooper's 1835 "Practice of Surgery"

- Imaging of Lower Extremities Amputations

- An amputation and regeneration blog

- Diving In, NC Well Magazine

- Limb Loss Education, University of Washington

- Mangled Extremity Severity Score

- Afghan amputees tell their stories at Texas gathering, Fayetteville Observer

- Can modern prosthetics actually help reclaim the sense of touch?, PBS Newshour