Annexation of Crimea by the Russian Empire

The territory of Crimea, previously controlled by the Crimean Khanate, was annexed by the Russian Empire on 19 April [O.S. 8 April] 1783.[1] The period before the annexation was marked by Russian interference in Crimean affairs, a series of revolts by Crimean Tatars, and Ottoman ambivalence. The annexation began many years of Russian rule in Crimea, which ended with the transfer of the territory to the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic in 1954. Russia annexed Crimea for a second time in March 2014.[2][3]

Prelude

Independent Crimea (1774–76)

Before Russia defeated the Ottoman Empire in the Russo-Turkish War of 1768–74, the Khanate, populated largely by Crimean Tatars, had been part of the Ottoman Empire. In the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca, which was the result of that war, the Ottoman Empire was forced to cede sovereignty over the Khanate, and allow it to become an independent state under Russian influence.[4] Tatars in Crimea had no desire for independence, and held a strong emotional attachment to the Ottoman Empire. Within two months of the signing of the treaty, the government of the Khanate sent envoys to the Ottomans, asking them to "destroy the conditions of independence". The envoys said that as Russian troops remained stationed in Crimea at Yeni-Kale and Kerch, the Khanate could not be considered independent. Nevertheless, the Ottomans ignored this request, not wishing to violate the agreement with Russia.[5][6] In the disorder that followed the Turkish defeat, Tatar leader Devlet Giray refused to accept the treaty at the time of its signing. Having been fighting Russians in the Kuban during the war, he crossed the Kerch Strait to Crimea and seized the city of Kaffa (modern Feodosia). Devlet subsequently seized the Crimean throne, usurping Sahib Giray. Despite his actions against the Russians, Russian Empress Catherine the Great recognised Devlet as Khan.[6]

At the same time, however, she was grooming her favourite Şahin Giray, who resided at her court, for the role.[6] As time went on, the rule of Devlet became increasingly untenable. In July of 1775, he sent a group of envoys to Constantinople to negotiate a reentry of the Crimean Khanate into the Ottoman Empire. This action was in direct defiance of the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca, which he asked the Ottomans to scrap. Famed diplomat Ahmed Resmî Efendi, who had helped draft the treaty, refused to provide any assistance to the Khanate, not wanting to start another disastrous war with Russia. Empress Catherine gave an order to invade Crimea in November 1776. Her forces quickly gained control of Perekop, at the entrance to the peninsula. In January 1777, Russian-supported Şahin Giray crossed into Crimea over the Kerch Strait, much as Devlet had done. Devlet, aware of his impending defeat, abdicated and fled to Constantinople. Şahin was installed as a puppet Khan, infuriating the Muslim population of the peninsula.[1] When he heard this news, Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid I noted "Şahin Giray is a tool. The aim of the Russians is to take Crimea."[6] Şahin, a member of the ruling House of Giray, attempted a series of reforms to "modernise" the Khanate. These included attempts to centralise power in the hands of the Khan, establishing "autocratic" rule, much as in Russia. Previously, power had been distributed between the leaders of different clans, called beys. He attempted to institute state taxation, a conscripted and centralised army, and to replace the traditional religion-based Ottoman legal system with civil law.[7] These reforms, aimed at disrupting the old Ottoman order, were despised by the Crimean populace.[8]

Crimean revolts (1777–82)

At the behest of Empress Catherine, Şahin allowed Russians to settle in the peninsula, further infuriating Crimeans. A group of these settlers had been sent to Yeni-Kale, which remained under Russian control following the installation of Şahin as Khan. Local residents banded together to prevent the Russian settlement, rebelling against Şahin. He sent the new conscript army he had created to quash the rebellion, only to see his forces defect to the rebels. Revolt spread across the peninsula, and rebel forces advanced on Şahin's palace in Bakhchisaray. Amidst this rebellion, exiled Crimeans in Constantinople pressed the Ottoman government to act.[7] Bowing to pressure, the government sent a fleet to Crimea, ostensibly to preserve the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca. Russia, however, was quicker to act. Russian forces arrived at Yeni-Kale in February 1778, crushing the revolt before the Ottoman fleet arrived. When the fleet arrived in March, it found that there were no rebels left to support. It fought a brief skirmish with the Russian navy off Akitar (modern Sevastopol), but was forced to flee. Şahin was reinstated as Khan.[7] Minor skirmishes between the Ottoman and Russian navies continued until October 1778, when the Ottoman fleet returned defeated to Constantinople.[8]

Over the following years, Şahin continued to try and reform the Khanate.[9] Support for his reform programme remained low, and it was seriously undermined by the decision of Empress Catherine to resettle the Crimean Pontic Greeks on the northern shores of the Azov Sea, outside the Khanate. That community, which was Christian, were an essential part of the Crimean merchant class, and had most readily supported Şahin's reforms. This resettlement caused significant damage to the Crimean economy, and further weakened the position of the Khan.[9] Recognising defeat in Crimea, the Ottoman Empire signed the Convention of Aynali Kavak in early 1779. In the agreement, the Ottomans recognised Şahin as Khan of Crimea, promised no further intervention in Crimea, and conceded that Crimea was under Russian influence. Crimeans could no longer expect support from the Ottomans. Şahin's reforms proceeded, gradually removing Tatars from positions of political influence. For a brief period, Crimea remained peaceful.[9]

A new rebellion, sparked by the continuing marginalisation of Tatars within the Khanate government, started in 1781.[10] Various clan leaders and their forces came together in the Taman, across the Kerch Strait from Crimea. In April of 1782, a large portion of Şahin's army defected to the rebels, and joined them in the Taman. Communication between rebel leaders, including two of Şahin's brothers, and the Crimean administrative elite was ongoing. Religious (ulama) and legal (kadı) officials, important parts of the old Ottoman order, openly declared their antipathy for Şahin. Rebel forces attacked Kaffa on 14 May [O.S. 3 May] 1782. Şahin's forces were swiftly defeated, and he was forced to escape to Russian-controlled Kerch. Rebel leaders elected Şahin's brother Bahadir Giray as Khan, and sent a message to the Ottoman government seeking recognition.[10] It was not long, however, before Empress Catherine dispatched Prince Grigory Potemkin to restore Şahin to power. No significant opposition was fielded against the invading Russians, and many rebels fled back across the Kerch Strait. As such, the Khan was restored to his position in October 1782.[11] By this time, however, he had lost the favour of both Crimeans and Empress Catherine. In a letter to a Russian advisor to Şahin, Catherine wrote "He must stop this shocking and cruel treatment and not give them [Crimeans] just cause for a new revolt".[10] As Russian troops entered the peninsula, work on the establishment of a Black Sea port for use by the Empire began. The city of Akitar was chosen as the site of the port, which would go on to house the newly created Black Sea Fleet.[12] Uncertainty about the sustainability of the restoration of Şahin Giray, however, led to an increase of support for annexing Crimea, spearheaded by Prince Potemkin.[1]

Annexation (1783)

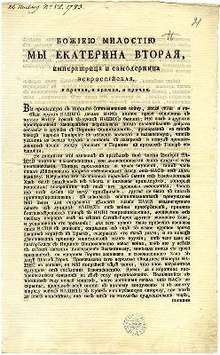

In March 1783, Prince Potemkin made a rhetorical push to encourage Empress Catherine to annex Crimea. Having just returned from Crimea, he told her that many Crimeans would "happily" submit to Russian rule. Encouraged by this news, Empress Catherine issued a formal proclamation of annexation on 19 April [O.S. 8 April] 1783.[1][12] Tatars did not resist the annexation. After years of turmoil, the Crimeans lacked the resources and the will to continue fighting. Many fled the peninsula, leaving for Anatolia.[13] Count Alexander Bezborodko, then a close advisor to the Empress, wrote in his diary that Russia was "forced" to annex Crimea:

The Porte has not kept good faith from the very beginning. Their primary goal has been to deprive the Crimeans of independence. They banished the legal khan and replaced him with the thief Devlet Giray. They consistently refused to evacuate the Taman. They made numerous perfidious attempts to introduce rebellion in the Crimea against the legitimate Khan Şahin Giray. All of these efforts did not bring us to declare war…The Porte never ceased to drink in each drop of revolt among the Tatars…Our only wish has been to bring peace to Crimea…and we were finally forced by the Turks to annex the area.[14]

This view was far from reality. Crimean "independence" had been a puppet regime, and the Ottomans had played little role in the Crimean revolts.[10] Crimea was incorporated into the Empire as Taurida Governorate. Later that year, the Ottoman Empire signed an agreement with Russia that recognised the loss of Crimea and other territories that had been held by the Khanate. The agreement, signed on 28 December 1783, was negotiated by Russian diplomat Yakov Bulgakov.[15][16]

References

- 1 2 3 4 M. S. Anderson (December 1958). "The Great Powers and the Russian Annexation of the Crimea, 1783–4". The Slavonic and East European Review. 37 (88): 17–41. JSTOR 4205010.

- ↑ Aglaya Snetkov (2014). Russia's Security Policy Under Putin: A Critical Perspective. Routledge. p. 163. ISBN 1136759689.

- ↑ Casey Michel (4 March 2015). "The Crime of the Century". The New Republic. Retrieved 2 March 2016.

- ↑ "When Catherine the Great Invaded the Crimea and Put the Rest of the World on Edge". Smithsonian.com. 4 March 2014. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- ↑ Alan W. Fisher (1970). The Russian Annexation of the Crimea 1772–1783. Cambridge University Press. pp. 57–59. ISBN 1001341082.

- 1 2 3 4 Alan W. Fisher (1978). The Crimean Tatars: Studies of Nationalities in the USSR. Hoover Press. pp. 59–62. ISBN 0817966633.

- 1 2 3 Alan W. Fisher (1978). The Crimean Tatars: Studies of Nationalities in the USSR. Hoover Press. pp. 62–66. ISBN 0817966633.

- 1 2 Virginia H. Aksan (1995). An Ottoman Statesman in War and Peace: Ahmed Resmi Efendi, 1700-1783. Brill. pp. 174–175. ISBN 9004101160.

- 1 2 3 Alan W. Fisher (1978). The Crimean Tatars: Studies of Nationalities in the USSR. Hoover Press. pp. 62–67. ISBN 0817966633.

- 1 2 3 4 Alan W. Fisher. The Crimean Tatars: Studies of Nationalities in the USSR. Hoover Press. pp. 67–69. ISBN 978-0-8179-6663-8.

- ↑ David Longley (30 July 2014). Longman Companion to Imperial Russia, 1689-1917. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-317-88219-0.

- 1 2 Alan W. Fisher (1970). The Russian Annexation of the Crimea 1772–1783. Cambridge University Press. pp. 132–135. ISBN 1001341082.

- ↑ Hakan Kırımlı (1996). National movements and national identity among the Crimean Tatars:(1905-1916). BRILL. pp. 2–7. ISBN 90-04-10509-3. Retrieved 21 June 2015.

- ↑ Nikolai Ivanovich Grigorovich (1879). Канцлер князь Александр Андреевич Безбородко в связи с событиями его времени [Chancellor A. A. Bezborodko in Connection with the Events of His Time]. Сборник Императорского русского исторического общества [Collection of the Imperial Russian Historical Society] (in Russian). 26. St. Petersburg: Imperial Russian Historical Society. pp. 530–532.

- ↑ Sir H. A. R. Gibb (1954). The Encyclopaedia of Islam. Brill Archive. p. 288.

- ↑ Sebag Montefiore (2000). The Prince of Princes: The Life of Potemkin. Macmillan. p. 258. ISBN 0312278152.