Archer family

|

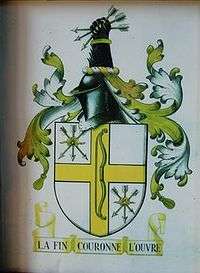

Coat of Arms of the Archer family | |

| Ethnicity | British |

|---|---|

| Place of origin | Hertfordshire, England |

| Connected families | Kermode, Mifflin, |

| Distinctions | Prominence in business, politics and farming |

| Estate | Brickendon, Landfall |

The Archer family are a notable family in Tasmania, Australia, prominent in society, business and politics of Tasmania for the last two centuries. They are best known today for their now world-heritage listed farm estates, Brickendon Estate and Woolmers Estate, but have contributed to many areas of Tasmania throughout their history. Other members of the family have been Mayors of Hertfordshire in England and influential in the American Civil War.

Politics

Among the family, there have been 7 members of the Tasmanian Parliament and numerous members of Longford Municipal Council.

| Name | House of Parliament | Years sitting | Born-Died |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thomas Archer | Legislative Council | 1827–1844[1] | 1790-1850 |

| Joseph Archer | Legislative Council | 1851–1853[2] | 1795-1853 |

| William Archer | Legislative Council/House of Assembly | 1851–1855(MLC)/1860-1862 & 1866-1868 (MHA)[3] | 1820-1874 |

| Robert Archer | House of Assembly | 1869–1871[4] | 1832-1914 |

| Basil Archer | House of Assembly | 1871–1872 [5] | 1841-1923 |

| William Henry Davies Archer | House of Assembly | 1882–1886 [6] | 1836-1928 |

| Frank Archer | House of Assembly | 1893–1902 [7] | 1836-1902 |

| Name | Position | Years Alderman | Born-Died |

|---|---|---|---|

| William Henry Davies Archer | Longford: Alderman, Council Warden, Treasurer | 1872-1894 | 1836-1928 |

| William Fulbert Archer[8] | Longford: Alderman, Council Warden | - | 1883–1952 |

| Robert Joseph Archer[9] | Longford: Alderman, Council Warden | - | 1832-1914 |

| Ludlow Archer | Longford: Alderman | - | 1857–1916[10] |

| Thomas Cathcart Archer[11] | Longford: Alderman, Council Warden | - | 1862-1934 |

Ancestors

William Minors (unknown-1668)

Captain William Minors was cousin of Thomas Archer and a Mayor of Hertford in 1662.[12]

Thomas Archer (unknown-1694)

Doctor Thomas Archer was an Alderman of Hertford. He served as Mayor of Hertford in 1681 and 1694, and died that year. His brothers were John, Henry and Joseph Archer. He had three children; John, William and Joseph.[12]

Thomas Archer (unknown-1734)

Only son of John Archer, and grandson of Thomas Archer (unknown-1694), Thomas Archer married Sarah Newton, daughter of Edmond Newton of Bengeo. His daughter Sarah died at birth, and he left one son, John Archer. He left considerable property upon death.[12]

John Archer (unknown-1752)

John Archer was the only son of Thomas Archer. He married Mary Bazeil (or Bassett) in 1752, and had two sons and one daughter; William Archer (unknown-1833), Henry Waldegrave Archer (unknown-1788) and Mary Archer (unknown-1805)

First generation

William Archer (unknown–1833)

William Archer was the eldest son of John Archer and therefore ancestor of all Tasmanian members of the Archer family. He was great great grandson of Thomas Archer (unknown-1667). He married Martha Kensey and was a miller by trade. He stayed in England until 1827 when he joined his sons in Tasmania. He died from a fall from a horse in 1833.[12]

Henry Waldegrave Archer (unknown–1788)

Henry Archer was the second son of John Archer and younger brother of William Archer (unknown-1833). He traveled to America, where he became a Major and volunteer adjutant to Anthony Wayne. He was granted the Brevet of Captain by an act of the US Congress on July 26, 1779 for bringing General Washington's missives safety to Congress.[13] Henry Archer went on to marry Rebecca Mifflin, cousin of Thomas Mifflin 1st Governor of Pennsylvania.[12][14] It was recorded in 1784 that he was appointed Lieutenant of Northampton, Massachusetts. He died in 1788 and was buried at the "Friends burial ground on the Corner of Arch and Fourth Streets", possibly Arch Street Friends Meeting House.[15]

Mary Archer (unknown-1805)

Mary Archer was daughter of John Archer. She married Doctor Frost, who died in 1787. She remaried Thomas George Street, owner of the London Courier and evening gazette. She died in 1805, having had no children.[12]

Second generation

William Archer (1788–1879)

William was the eldest son of William Archer of Hertfordshire. He arrived in Tasmania in 1821 on the ship Aguilar, where he settled at Brickendon - the second of the families two most famous homesteads - and began his farm with 30 merino sheep he had brought with him from England. He became a highly successful farmer and cooperated highly with his brother at neighbouring Woolmers. He was repeatedly asked to become a member of the Legislative Council but declined; he did however accept a position of Magistrate in 1835. During his life he became a noted anti-transportationist. He died on March 24, 1879. He was reported as leaving either three or four sons and one or two daughters, with his second son inheriting Brickendon and his first Saundridge.[16][17] His fourth son, G F Archer, became the Reverend of Torquay (modern Devonport).[17][18]

Thomas Archer (1790–1850)

Thomas Archer I was born on the 3rd of April 1790, in Hertfordshire, England, the fourth but second surviving son of William Archer. His father was a successful miller. The Archer family's influence on Tasmania started when Thomas Archer I immigrated from Hertfordshire, England to the Australian colonies. Thomas I originally arrived in Sydney in 1812 as a clerk, before quickly being transferred to then Van Diemens Land, where he quickly rose through the ranks under Governor Macquarie.

He was appointed head clerk of Port Dalrymple (Now George Town) in 1813, becoming magistrate in 1814, coroner in 1816 of all of Cornwall County, which at the time encompassed nearly half of Tasmania, and magistrate for the same 18 months later. In 1817 he was appointed deputy assistant commissary of Cornwall, and in December of that year he was appointed commissary of Hobart. In 1819 he was returned to Port Dalrymple as head commissary of the town. However, by 1821 he had retired following quarrels with officers of the commandant. However, in the meantime he had acquired 2,000 acres at what is now Woolmers, and he returned there to run his farm. By 1825 he had reached 6,000 acres.[19]

He was progressively joined by his brothers, who immigrated from England to build the Panshanger, Brickendon, Northbury, Fairfield, Cheshunt, Woodside, Palmerston and Saundridge estates between them. In 1826 he was appointed part of the first Legislative Council of Tasmania, which he remained a member of until he resigned due to ill health in 1845. In 1842, he joined the bank founded by his brothers two years earlier, Archer, Gilles and Co,[20] however the banks failure in 1844 lost significant money for Thomas and the bank was absorbed by the Union Bank of Australia, which would go on to become ANZ[20] Thomas died of dropsy in 1850.[21]

Edward Archer (1793–1879)

Edward Archer was the first surviving son of William Archer of Hertfordshire. He settled in Tasmania at Northbury, which he built the final house of in 1862.[22] He died in 1862, leaving eight sons and two daughters. His wife, Sussanah Archer, survived until 1890 and was herself a notable member of the local community, being a contributor to the Longford Wesleyan Church, of which she laid the foundation stone. His sons went on to inherit or buy various properties, including Longford Hall, Landfall and Huntsworth. His eldest son, Basil, went on to become a member of the Tasmanian parliament and his 8th son, Ludlow, inherited Northbury and went on to become a Councilor of Longford Municipality and Justice of the Peace.[10][23]

Joseph Archer (1795–1853)

Joseph Archer was the younger brother of Thomas I. He immigrated to Van Diemens Land following his brothers success, where he built the Greek-revival Panshanger Estate in Longford. He was highly successful until the bankruptcy of the family bank, Archer, Gilles and Co which in 1884 left him with debts of 70,000 pound, which he paid off before his death. He became a member of the Tasmanian Legislative Council in 1847, and held the post till his sudden death in 1853.[24] He died without heir and his estate was inherited by his nephew, also Joseph Archer.[25] The property remained in his hands until 1908, when it was sold to the Mills family. It is presently a B&B and 6,000 acre farm.[26]

Third Generation

Thomas Archer II (1817–1844)

Thomas Archer II was the only son of Thomas Archer I. He died of scarlet fever in 1844 at the age of 27, predeceasing the rest of his family.[27] His wife died in 1874 in a fatal carriage crash while returning from a ball in Launceston,[28] and his father died six years after him in 1850. He left a four-year-old son.[29]

William Archer (1820–1874)

William Archer was the second son of Thomas Archer I. As he was not in line to inherit the estate, he pursued his own career and built Cheshunt House. He became a noted parliamentarian, architect and botanist. His many architectural projects include many of his families properties, most notably Woolmers[30] itself but also Saudridge at Cressy[31] and the non-archer Mona Vale.[32] He in 1856 was appointed a Magistrate of Tasmania, and the same year elected Member for Westbury in the Tasmanian House of Assembly. Due to ill health he resigned his post in 1862.[33]

Joseph Archer (1823–1914)

The second Joseph Archer was the son of Thomas Archer I. He married the daughter of the two time Premier of Tasmania, William Weston. He was granted Fairfield Estate by his father and later he inherited Panshanger and Burlington estates from his uncle, also Joseph. In 1862 he was elected a member of the Tasmanian Legislative Council for Longford, which he represented for ten years. He sold his property Panshanger in 1908 to the Mills family, after a period of ill health, and he sold Burlington shortly after. Fairfield had been sold some time before that. He died in 1914, leaving three sons and three daughters.[25]

Robert Joseph Archer (1832–1914)

Robert Archer (born 1832) was the eldest son of William Archer (1788-1879), inheriting his estate of Saundridge. He became a well known local farmer, and member of Longford Municipal Council. He was briefly a member of the House of Assembly, representing Ringwood (modern Cressy). He was a state magistrate for some years. He sold his property to the Thirkell family (of Angela Thirkell fame) around 1875 and moved to Melbourne, where he died in 1914.[9] His son Alexander became a successful lawyer, in partnership originally with John Clemons.[34]

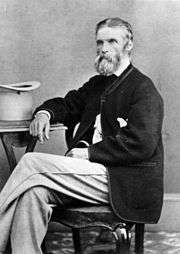

William Henry Davies Archer (1836–1928)

The second son of William Archer (1788-1879), William inherited Brickendon Estate from his father. He was educated in Tasmania and England, graduating from Trinity College, Cambridge in 1859 with a Bachelor of Arts and 1860 with a Bachelor of Laws, receiving a Masters of Laws in 1863. In 1862 he had finished courses at the Middle Temple and was able to serve at the bar. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society, London in 1860. He married Aphra Gertrude Clerke, daughter of Alexander Clerke,[12] a member of parliament for Tasmania.

In 1869 he was appointed a magistrate of Tasmania, and in 1883 a state coroner. From 1882-1887 he was a member of the House of Assembly for Norfolk Plains, during which time he was offered the posts of Speaker, Treasurer and Chief Secretary in succession and declined each. He became a member of the Royal Commissions into Education and Prisons, and was Tasmania's representative to the 1878 Paris World Fair. In 1872 he was elected a member of Longford Municipal Council, on which he served for 22 years, becoming for the last 17 years Warden. He became Treasurer of the Municipality during his time, and served on the Longford Show Society Committee, as well as being chairman of the Boards of Health, Rabbits, Fruits and Advice.

He died in 1828. He left two daughters, and a son, who inherited Brickendon.[35]

Basil Archer (1841–1923)

Basil Archer was the eldest son of Edward Archer (1793-1879). He settled at the estate of Woodside in partnership with his brother Daniel, but brought out his brothers share, going on to additionally purchase the properties of Iveridge, Melrose and Inglewood during his lifetime. He was a Methodist lay leader for his local church for 52 years, as well as serving as a member of Longford Municipal Council for 25 years[36] and was briefly a member of the House of Assembly 1871-1872 for Ringwood (modern Cressy).[5] He died of heart failure suddenly while visiting Adelaide.[36]

Ludlow Archer (1857–1916)

Ludlow Archer was the youngest son of Edward Archer (1793-1879), from who he inherited the estate of Northbury. During his life he was Captain of the Esk Detachment of Riflemen, Alderman of Longford Municipality Council, Justice of the Peace and board member of the Longford Water Trust. He married Alice McLeod in 1895 at the Holy Trinity Church, Launceston. He died at home in 1916, leaving three children - Ludlow, Angus and Errol.[10]

Fourth Generation

Thomas Archer III (1840–1890)

The only son of Thomas Archer II, Thomas Archer III was born in 1840 – 4 years before his father died of scarlet fever. He was a state magistrate for 24 years. He died in 1890 at the Blenheim Hotel, Longford, leaving a wife, three sons and three daughters. The eldest, Thomas Archer IV, inherited Woolmers.[37] His wife, Louisa Kate, died in 1908 in St Kilda, Victoria.[38]

William Fulbert Archer (1883–1952)

William Fulbert Archer was the only son of William William Henry Davies Archer of Brickendon. He studied at Cambridge, graduating with Bachelor of Arts, and returning home where he inherited the estate from his father upon his death. He married Phyllis Bisdee and ran the farm during his life. He became a member of Longford Municipal Council for many years and Council Warden, and was patron of the Northern Agricultural Society. He was a coroner for the district as well. He was survived by two sons, Peter and Kerry, and a daughter Rose.[8]

Fifth Generation

Thomas Archer IV

Thomas Cathcart Archer was born in 1862, son of Thomas Archer III. He was educated at Launceston Church Grammar School and he inherited Woolmers upon his fathers death and was during his life promoted community and sports movements. He played cricket in North vs South state matches and was President of the Longford Golf Club and patron of the Tamar Yacht Club at the time of his death and previously commodore of it. He was also a member of Longford Show Council and a member of Longford Municipal Council for 32 years as well as a Justice of the Peace. He married Eleanor Mary Harrap and had one son, Thomas Edward Cathcart Archer (Thomas Archer V). He died on the 11th of August, 1934 while in Melbourne.[11]

Legacy

A book on the family, titled The Archers of Van Diemens Land : a history of pioneer pastoral families was published in 1991, written by Neil Chick.[39] Two of their homes, Woolmers and Brickendon, are world heritage listed as part of the Australian Convict Sites area.

Many of the properties built by the family - Northbury (Longford), Saundridge (Cressy), Panshanger (Carrick), Cheshunt (Meander Valley), Fairfield (Cressy), Palmerston (Cressy) and Woodside (Cressy) are all listed on the Tasmanian Heritage Register.[40] Cheshunt House, designed and owned by William Archer (1820–1874), was featured on a stamp issued by Australia Post in 2004.[41]

One line of the family still owns and farms Brickendon Estate, while another line owns an award winning dairy based out of the family estate Landfall.[42][43]

References

- ↑ "Members of the Legislative Council of Van Diemen's Land 1825-1856". parliament.tas.gov.au. Office of the Parliament of Tasmania. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- ↑ "Archer, Joseph 1851-1853". parliament.tas.gov.au. Office of the Parliament of Tasmania. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- ↑ "Archer, WIlliam". parliament.tas.gov.au. Office of the Parliament of Tasmania. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- ↑ "Archer, Robert 1869-1871". parliament.tas.gov.au. Office of the Parliament of Tasmania. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- 1 2 "Archer, Basil 1871-1872". parliament.tas.gov.au. Office of the Parliament of Tasmania. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- ↑ "Archer, William Henry Davies 1882-1886". parliament.tas.gov.au. Office of the Parliament of Tasmania. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- ↑ "Archer, Frank 1893-1902". parliament.tas.gov.au. Office of the Parliament of Tasmania. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- 1 2 "Archer, William Fulbert (1883–1952)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Australian Dictionary of Biography. Retrieved 2 June 2014.

- 1 2 "Archer, Robert Joseph (1832–1914)". Australian Dictionary of Autobiography. Australian Dictionary of Autobiography. Retrieved 2 June 2014.

- 1 2 3 "LUDLOW ARCHER AND FAMILY". Archives.Tas.Gov. Tasmanian Heritage Office. Retrieved 2 June 2014.

- 1 2 "Archer, Thomas Cathcart (1862–1934)'". oa.anu.edu.au. Obituaries Australia, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Retrieved 24 April 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Burke, Sir Bernard (1891). A genealogical and heraldic history of the colonial gentry (in two volumes) (1st ed.). Harrison of London. p. 189. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- ↑ Journals of Congress: Containing the proceedings from Sept. 5, 1774 to [3d day of November 1788]. United States. Continental Congress. p. 229. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- ↑ "Mifflin Family Papers, 1689-1877". quod.lib.umich.edu. William L. Clements Library University of Michigan. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- ↑ The Archers of Van Diemens Land (1st ed.). Pedigree Press. 1991. p. 69.

- ↑ "Archer, William (1788–1879)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Australian Dictionary of Biography. Retrieved 2 June 2014.

- 1 2 "Correspondence from reader". Launceston Examiner. 27 March 1879. Retrieved 2 June 2014.

- ↑ "Family Notices". Launceston Examiner. 21 January 1878. Retrieved 2 June 2014.

- ↑ "Archer, Thomas (1790–1850)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Australian Dictionary of Biography. Retrieved 27 June 2014.

- 1 2 Archer, T. "Archer, GIlles and Co" (PDF). UTAS. Retrieved May 21, 2014.

- ↑ "ARCHER FAMILY". UTas. Retrieved 21 May 2014.

- ↑ "'Northbury', Longford, Tasmania; Department of Film Production; c. 1965;". eHive. eHive. Retrieved 2 June 2014.

- ↑ "Archer, Susannah (1819–1890)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Australian Dictionary of Biography. Retrieved 2 June 2014.

- ↑ "Archer, Joseph". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Retrieved 21 May 2014.

- 1 2 "Archer, Joseph". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Retrieved 21 May 2014.

- ↑ "Panshanger - History". Panshanger. Retrieved 21 May 2014.

- ↑ "Archer, Thomas William (1817–1844) Obituary". oa.anu.edu.au. Obituaries Australia. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- ↑ "FATAL CARRIAGE ACCIDENT.". The Cornwall Chronicle. 9 Mar 1874. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- ↑ "Dynasties - Archers - Key Dates". abc.net.au. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- ↑ "National Heritage Places - Woolmers Estate". Department of Environment, Commonwealth of Australia. Retrieved 21 May 2014.

- ↑ "'Saundridge', near Cressy, Tasmania; Unknown; c. 1960s;". eHive. Retrieved 21 May 2014.

- ↑ Historic Homesteads of Australia. Council of Australian Trusts. 1969. p. 243.

- ↑ "Obituary: William Archer". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Retrieved 21 May 2014.

- ↑ "Archer, Alexander (1862–1945)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Australian Dictionary of Biography. Retrieved 2 June 2014.

- ↑ "Archer, William Henry Davies (1836–1928)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Australian Dictionary of Biography. Retrieved 2 June 2014.

- 1 2 "Obituary Archer, Basil (1841–1923)". oa.anu.edu.au. Obituaries Australia. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- ↑ "Archer, Thomas Chalmers (1840–1890)". oa.anu.edu.au. Obituaries Australia. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- ↑ "Family Notices". The Argus. 5 Mar 1908. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- ↑ "1991, English, Book, Illustrated edition:". trove.nla.gov.au. National Library of Australia. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- ↑ "Tasmanian Heritage Register" (PDF). heritage.tas.gov.au. Heritage Tasmania. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- ↑ "Stamp Bulletin" (PDF). auspost.com.au. Australia Post. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- ↑ "Creaming new opportunity to be milk jug of the world". The Australian. 20 October 2012. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- ↑ "The Archers". tfga.com.au. Tasmanian Farmers & Graziers Association. Retrieved 22 September 2014.