Assassination of Spencer Perceval

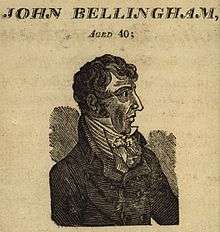

Spencer Perceval, the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, was shot and killed in the lobby of the House of Commons in London, at about 5:15 pm on Monday 11 May 1812. His assailant was John Bellingham, a Liverpool merchant with a grievance against the government. Bellingham was detained and, four days after the murder, was tried, convicted and sentenced to death. He was hanged at Newgate Prison on 18 May.

Perceval had led the Tory government since 1809, during a critical phase of the Napoleonic Wars. His determination to prosecute the war using the harshest of measures caused widespread poverty and unrest on the home front; thus the news of his death was a cause of rejoicing in the worst affected parts of the country. Despite initial fears that the assassination might be linked to a general uprising, it transpired that Bellingham had acted alone, protesting against the government's failure to compensate him for his treatment a few years previously, when he had been imprisoned in Russia for a trading debt. Bellingham's lack of remorse, and apparent certainty that his action was justified, raised questions about his sanity, but at his trial he was judged to be legally responsible for his actions.

After Perceval's death, Parliament made generous provision to his widow and children, and approved the erection of monuments. Thereafter his ministry was soon forgotten, his policies reversed, and he is generally better known for the manner of his death than for any of his achievements. Later historians have characterised Bellingham's hasty trial and execution as contrary to the principles of justice. The possibility that he was acting within a conspiracy, on behalf of a consortium of Liverpool traders hostile to Perceval's economic policies, is the subject of a 2012 study.

Background

Biographical details

Spencer Perceval was born on 1 November 1762, the second son from the second marriage of John Perceval, 2nd Earl of Egmont. He attended Harrow School and, in 1780, entered Trinity College, Cambridge, where he was a noted scholar and prizewinner. A deeply religious boy, at Cambridge he became closely aligned with evangelicalism, to which he remained faithful all his life.[1] Under the rule of primogeniture, Perceval had no realistic prospect of a family inheritance, and needed to earn his living; on leaving Cambridge in 1783, he entered Lincoln's Inn to train as a lawyer. After being called to the bar in 1786, Perceval joined the Midland Circuit, where his family connections helped him to acquire a lucrative practice.[2] In 1790 he married Jane Wilson, the couple having eloped on her 21st birthday.[3] The marriage proved happy and prolific; twelve children (six sons and six daughters) were born over the following 14 years.[4][5]

Perceval's politics were highly conservative, and he acquired a reputation for his attacks on radicalism. As a junior prosecuting counsel in the trials of Thomas Paine and John Horne Tooke, he was noticed by senior politicians in the ruling Pitt ministry. In 1796, having refused the post of Chief Secretary for Ireland,[5] Perceval was elected to parliament as the Tory member for Northampton, and won acclaim in 1798 with a speech defending Pitt's government against attacks by the radicals Charles James Fox and Francis Burdett. He was generally seen as a rising star in his party; his short stature and slight build earned him the nickname "Little P".[2]

After William Pitt's resignation in 1801, Perceval served as Solicitor General, and then as Attorney General, in the Addington ministry of 1801–04,[6] continuing in the latter office through Pitt's second government, 1804–06. Perceval's deep evangelical convictions led him to his unwavering opposition to the Catholic Church and to Catholic emancipation,[2] and his equally fervent support for the abolition of the slave trade, when he worked with fellow evangelicals such as William Wilberforce to secure the passage of the Slave Trade Act 1807.[7]

When Pitt died in 1806 his government was succeeded by the cross-party "Ministry of All the Talents", under Lord Grenville.[8] Perceval remained in opposition during this short-lived ministry,[5] but when the Duke of Portland formed a new Tory administration in March 1807, Perceval took office as Chancellor of the Exchequer and Leader of the House of Commons.[9] Portland was elderly and ailing, and on his resignation in October 1809, Perceval succeeded him as First Lord of the Treasury—the formal title by which prime ministers were then known—after a wounding internecine leadership struggle.[2] In addition to his duties as head of the government he retained the Chancellorship, largely because he could find no minister of appropriate stature who would accept the office.[10]

Troubled times

Perceval's government was weakened by the refusals to serve of former ministers such as George Canning and William Huskisson.[11][12] It faced massive problems at a time of considerable industrial unrest and at a low point in the war against Napoleon. The unsuccessful Walcheren Campaign in the Netherlands was unravelling,[10] and the army of Sir Arthur Wellesley, the future Duke of Wellington, was pinned down in Portugal.[13] At the outset of his ministry Perceval enjoyed the strong support of King George III, but in October 1810 the king lapsed into insanity and was permanently incapacitated.[14] Perceval's relationship with the Prince of Wales, who became Prince Regent, was initially far less cordial, but in the following months he and Perceval established a reasonable affinity, perhaps motivated in part by the prince's fear that the king might recover and find his favourite statesman deposed.[2]

When the final British forces withdrew from Walcheren in February 1810,[15] Wellington's force in Portugal was Britain's only military presence on the continent of Europe. Perceval insisted that it stayed there, against the advice of most of his ministers and at great cost to the British exchequer.[13][16] Ultimately this decision was vindicated, but for the time being his main weapon against Napoleon was the Orders in Council of 1807, inherited from the previous ministry. These had been issued as a tit-for-tat response to Napoleon's Continental System, a measure designed to destroy Britain's overseas trade.[17] The Orders permitted the Royal Navy to detain any ship thought to be carrying goods to France or its continental allies. With both warring powers employing similar strategies, world trade shrank, leading to widespread hardship and dissatisfaction in key British industries, particularly textiles and cotton.[18] There were frequent calls for modification or repeal of the Orders,[19] which damaged relations with the United States to the point that, by early 1812, the two nations were on the brink of war.[18][20]

At home, Perceval upheld his earlier reputation as scourge of radicals, imprisoning Burdett and William Cobbett, the latter of whom continued to attack the government from his prison cell.[21] Perceval was also faced with the anti-machine protests known as "Luddism",[22] to which he reacted by introducing a bill making machine-breaking a capital offence; in the House of Lords the youthful Lord Byron called the legislation "barbarous".[23] Despite these difficulties Perceval gradually established his authority, so that in 1811 Lord Liverpool, the war minister, observed that the Prime Minister's authority in the House now equalled that of Pitt.[24] Perceval's use of sinecures and other patronage to secure loyalties meant that by May 1812, despite much public protest against his harsh policies, his political position had become unassailable.[25] According to the humorist Sydney Smith, Perceval combined "the head of a country parson with the tongue of an Old Bailey lawyer".[26]

Early in 1812 agitation for repeal of the Orders in Council increased. After riots in Manchester in April, Perceval consented to a House of Commons enquiry into the operation of the Orders; hearings began in May.[27] Perceval was expected to attend the session on 11 May 1812; among the crowd in the lobby awaiting his arrival was a Liverpool merchant, John Bellingham.[28]

John Bellingham

Early life

Bellingham was born in about 1770, in the county of Huntingdonshire. His father, also named John, was a land agent and miniaturist painter; his mother Elizabeth was from a well-to-do Huntingdonshire family. In 1779 John senior became mentally ill, and, after confinement in an asylum, died in 1780 or 1781. The family were then provided for by William Daw, Elizabeth's brother-in-law, a prosperous lawyer who arranged Bellingham's appointment as an officer cadet on board the East India Company's ship Hartwell. En route to India the ship was wrecked; Bellingham survived and returned home.[29] Daw then helped him to set up in business as a tin plate manufacturer in London, but after a few years the business failed, and Bellingham was made bankrupt in 1794.[30] He appears to have escaped debtors' prison, perhaps through the further intervention of Daw. Chastened by this experience, he decided to settle down, and obtained a post as a book-keeper with a firm engaged in trade with Russia.[29] He worked hard, and was sufficiently regarded by his employers to be appointed in 1800 as the firm's resident representative in Archangel, Russia. On his return home, Bellingham set up his own trading business, and moved to Liverpool. In 1803 he married Mary Neville from Dublin.[31]

In Russia

In 1804 Bellingham returned to Archangel to supervise a major commercial venture, accompanied by Mary and their infant son.[32] His business completed, in November he prepared to return home, but was detained on account of a supposed unpaid debt. This arose from losses incurred by a business associate for which Bellingham was deemed liable. He denied any responsibility for the debt; his detention, he thought, was an act of revenge by powerful Russian merchants who—erroneously—thought that he had frustrated an insurance claim relating to a lost ship.[31] Two arbitrators appointed by the governor of Archangel determined that he was responsible for a sum of 2,000 roubles (about £200), a fraction of the original amount claimed. Bellingham rejected this judgement.[33]

With the issue still unresolved, Bellingham obtained passes for him and his family to travel to the Russian capital, St Petersburg. In February 1805, as they prepared to set out, Bellingham's pass was revoked; Mary and the child were permitted to proceed, but he was arrested and imprisoned in Archangel. When he sought help from Lord Granville Leveson-Gower, the British ambassador in St Petersburg, the matter was dealt with by the British consul, Sir Stephen Shairp, who informed Bellingham that as the dispute involved a civil debt, he could not interfere.[34] Bellingham remained in custody in Archangel until November 1805, when a new city governor ordered his release and allowed him to join Mary in St Petersburg. Here, instead of arranging his family's swift return to England, Bellingham laid charges against the Archangel authorities for false imprisonment, and demanded compensation. In doing so he outraged the Russian authorities, who in June 1806 ordered his imprisonment.[35] According to his later account, he was "often marched publicly through the city with gangs of felons and criminals of the worse description [to the] heart-rending humiliation of himself".[36]

Mary had meanwhile returned to England with her son (she was pregnant with her second child), eventually settling in Liverpool where she set up a millinery business with a friend, Mary Stevens.[37] For the next three years Bellingham made constant demands for release and compensation, seeking help from Shairp, Leveson-Gower, and the latter's successor as ambassador, Lord Douglas.[38] None were prepared to intercede on his behalf: "Thus", he later wrote when petitioning for redress, "without having offended any law, either civil or criminal, and without having injured any individual ... was your Petitioner bandied from one prison to another".[36] Bellingham's position worsened in 1807, when Russia signed the Treaty of Tilsit and aligned itself with Napoleon.[39] Two further years passed before, after a direct petition to Tsar Alexander, he was released and ordered to leave Russia. He arrived in England, uncompensated, in December 1809, determined to secure justice.[40]

Seeking redress

On his return to England Bellingham spent six months in London, seeking compensation for the imprisonment and financial losses he had suffered in Russia. He considered the British authorities were responsible, through their neglect of his repeated requests for help. Successively he petitioned the Foreign Office, the Treasury, the Privy Council, and Perceval himself;[41] in each case his claims were politely rejected. Defeated and exhausted, in May 1811 Bellingham accepted his wife's ultimatum to abandon his campaign or otherwise lose her and his family. He joined her in Liverpool to begin life afresh.[42]

During the following 18 months, Bellingham worked to rebuild his commercial career, with modest success. Mary continued to work as a milliner. The fact that he remained uncompensated continued to rankle. In December 1811 he returned to London, ostensibly to conduct business there, but in reality to resume his campaign for redress.[43] He petitioned the Prince Regent,[44] before resuming his efforts with the Privy Council, the Home Office and the Treasury, only to receive the same polite refusals as before.[45] He then sent a copy of his petition to every member of parliament, again to no avail.[46] On 23 March 1812 he wrote to the magistrates at Bow Street Magistrates' Court, arguing that the government had "completely endeavoured to close the door of justice",[47] and asking the court to intervene. He received a perfunctory reply.[45] After consulting his own MP, Isaac Gascoyne, Bellingham made a final attempt to present his case to the government. On 18 April he met with a Treasury official, Mr Hill, to whom he said that if he could get no satisfaction, he would take justice into his own hands. Hill, not perceiving these words as a threat, told him he should take whatever action he deemed proper.[48] On 20 April, Bellingham purchased two .50 calibre (12.7 mm) pistols from a gunsmith of 58 Skinner Street. He also had a tailor sew an inside pocket to his coat.[49]

Assassination

House of Commons, 11 May 1812

Bellingham's presence in the House of Commons lobby on Monday 11 May, caused no particular suspicion; he had made several recent visits, sometimes asking journalists to confirm specific ministers' identities.[50][51] Bellingham's activities earlier that day did not overtly indicate a man preparing desperate measures.[52] He had spent the morning writing letters and visiting his wife's business partner, Mary Stevens, who was in London at the time. In the afternoon he had accompanied his landlady and her son on a visit to the European Museum, in the St James's district of London. From there he made his way alone to the parliament buildings in Westminster, arriving in the lobby shortly before five o'clock.[53][54]

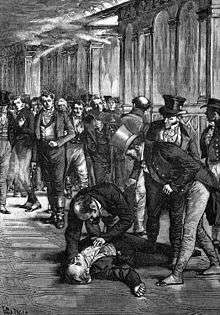

In the House, as the session began at 4.30 pm, the Whig MP Henry Brougham, a leading opponent of the Orders, drew attention to the Prime Minister's absence and remarked that he ought to be there. A messenger was sent to fetch Perceval from Downing Street, but met him in Parliament Street (Perceval having decided to walk and dispense with his usual carriage) on his way to the House, where he arrived at about 5.15.[55] As Perceval entered the lobby, he was confronted by Bellingham who, drawing a pistol, shot the Prime Minister in the chest. Perceval staggered forward a few steps and exclaimed "I am murdered!" before falling face down at the feet of William Smith, the MP for Norwich. (It was also variously reported Perceval had said "Murder" or "Oh my God".) Smith only realised that the victim was Perceval when he turned the body face upwards.[56][57] By the time he had been carried into an adjoining room and propped up on a table with his feet on two chairs, he was senseless, although there was still a faint pulse. When a surgeon arrived a few minutes later, the pulse had stopped, and Perceval was declared dead.[58]

In the pandemonium that followed, Bellingham sat quietly on a bench as Perceval was carried into the Speaker's quarters. In the lobby, such was the confusion that, according to a witness, had Bellingham "walked quietly out into the street, he would have escaped, and the committer of the murder would never have been known".[59] As it was, an official who had seen the shooting identified Bellingham, who was seized, disarmed, manhandled and searched. He remained calm, submitting to his captors without a struggle.[60] When asked to explain his actions, he replied that he was rectifying a denial of justice on the part of the government.[61]

The Speaker ordered that Bellingham be transferred to the Serjeant-at-Arms's quarters, where MPs who were also magistrates would conduct a committal hearing under the chairmanship of Harvey Christian Combe. The makeshift court heard evidence from eyewitnesses to the crime, and sent messengers to search Bellingham's lodgings.[62] The prisoner kept his composure throughout; although warned against self-incrimination, he insisted on explaining himself: "I have been ill-treated ... I have sought redress in vain. I am a most unfortunate man and feel here"—placing hand on heart—"sufficient justification for what I have done."[61] He had, he said, exhausted all proper avenues, and had made it clear to the authorities that he proposed to take independent action. He had been told to do his worst: "I have obeyed them. I have done my worst, and I rejoice in the deed."[63] At around eight o'clock, Bellingham was formally charged with Perceval's murder, and was committed to Newgate Prison to await trial.[64]

Reaction

Reports of the assassination spread quickly; in his history of the times, Arthur Bryant records the crude delight with which the news was received by hungry workers who had received nothing but woe from Perceval's government.[65] In his prison cell, Cobbett understood their feelings; the shooting had "ridded them of one whom they looked upon as the leader among those whom they thought totally bent on the destruction of their liberties".[66] The scenes outside the Palace of Westminster as Bellingham was taken out for transfer to Newgate were consistent with this mood; Samuel Romilly, the law reformer and MP for Wareham,[67] heard from the assembled crowd "the most savage expressions of joy and exultation ... accompanied with regret that others, and particularly the attorney general, had not shared the same fate".[68] The throng surged around the hackney coach carrying Bellingham; many tried to shake his hand, others mounted the coach-box and had to be beaten off with whips.[69] He was hustled back into the building, and kept there until the disorder had died down sufficiently for him to be moved, with a full military escort.[69]

Among the governing classes there were initial fears that the assassination might be part of a general insurrection, or might spark one.[70] The authorities took precautions; the Foot Guards and mounted troops were deployed, as was the City militia, while local watches were reinforced.[69] In contrast to the public's evident approval of Bellingham's actions, the mood among Perceval's friends and colleagues was sombre and sorrowful. When parliament met the next day, George Canning spoke of "a man ... of whom it might with particular truth be said that, whatever was the strength of political hostility, he had never before that last calamity provoked a single enemy".[71] After further tributes from government and opposition members, the House moved a grant of £50,000 and an annuity of £2,000 to Perceval's widow, which provision, slightly amended, was approved in June.[72]

The regard in which Perceval was held by his peers was made evident in an anonymous 1812 poem, "Universal Sympathy, or, The Martyr'd Statesman":[73]

| “ |

Such was his private, such his public life, |

” |

Proceedings

Preliminaries

An inquest into Perceval's death was held on 12 May, at the Rose and Crown public house in Downing Street. Among those who gave evidence were Gascoyne, Smith, and Joseph Hume, a doctor and Radical MP. He had helped to detain Bellingham, and now testified that from his controlled behaviour after the shooting, Bellingham appeared "perfectly sane".[74] The coroner duly registered the cause of death as "wilful murder by John Bellingham".[75] Armed with this verdict the Attorney General, Sir Vicary Gibbs, requested the Lord Chief Justice to arrange the earliest possible trial date.[76]

In Newgate prison, Bellingham was questioned by magistrates. His calm demeanour and poise led them, unlike Hume, to doubt his sanity, although his keepers had observed no signs of unbalanced behaviour.[77] James Harmer, Bellingham's solicitor, knew that insanity would provide the only conceivable defence for his client, and despatched agents to Liverpool to make enquiries there.[78] While awaiting their reports he learned from an informant that Bellingham's father had died insane;[79] he also heard evidence of Bellingham's supposed derangement from Ann Billett, the prisoner's cousin, who had known him from childhood.[80] On 14 May a grand jury met in the Sessions House, Clerkenwell, and after hearing evidence from the eyewitnesses, found "a true Bill against John Bellingham for the murder of Spencer Perceval".[81] The trial was arranged to take place the next day, Friday 15 May 1812, at the Old Bailey.[82]

When Bellingham received news of his forthcoming trial he asked Harmer to arrange for him to be represented in court by Brougham and Peter Alley, the latter an Irish lawyer with a reputation for flamboyance. Confident of his acquittal, Bellingham refused to discuss the case further with Harmer, and spent the afternoon and evening making notes. After drinking a glass of porter, he went to bed and slept soundly.[82]

Trial

The trial began at the Old Bailey on Friday 15 May 1812, under the presiding judge Sir James Mansfield, Chief Justice of the Court of Common Pleas.[83] The prosecuting team was led by the Attorney General, Gibbs, whose assistants included William Garrow, himself a future Attorney General.[84][85] Brougham having declined, Bellingham was represented by Alley, assisted by Henry Revell Reynolds.[83] The law at that time limited the role of defending counsel in capital cases; they could advise on points of law, and could examine and cross-examine witnesses, but otherwise Bellingham would have to present his own defence.[48][86]

After Bellingham had entered a not guilty plea, Alley asked for a postponement to allow him time to locate witnesses who could attest to the prisoner's insanity. This was opposed by Gibbs as a mere ploy to delay justice; Mansfield concurred, and the trial proceeded.[87] Gibbs then summarised the prisoner's business activities before meeting misfortune in Russia—"whether through his own misconduct or by the justice or injustice of that country, I know not".[88] He recounted Bellingham's unsuccessful efforts to obtain redress, and the consequent growth of a desire for revenge.[89]

Having described the shooting, Gibbs dismissed the possibility of insanity, maintaining that Bellingham was, at the time of the deed, fully in control of his actions.[90] Numerous eyewitnesses testified to what they had seen in the Commons lobby. The court also heard from a tailor who, shortly before the attack had, on Bellingham's instructions, modified the latter's coat by adding a special inside pocket, in which Bellingham had concealed his pistols.[91][92]

When Bellingham rose, he thanked the attorney general for rejecting the "insanity" strategy: "I think it is far more fortunate that such a plea ... should have been unfounded, than it should have existed in fact".[93] He began his defence by asserting that "all the miseries which it is possible for human nature to endure" had fallen on him.[94] He then read the petition that he had sent to the Prince Regent, and recalled his fruitless dealings with various government agencies. In his view the principal blame lay not with "that truly amiable and highly lamented individual, Mr Perceval", but with Leveson-Gower, the ambassador in St Petersburg who he felt had originally denied him justice, and who he said deserved the shot rather than the eventual victim.[95]

Bellingham's main witnesses were Ann Billett and her friend, Mary Clarke, both of whom testified to his history of derangement, and Catherine Figgins, a servant in Bellingham's lodgings. She had found him recently confused, but otherwise an honest and admirable lodger.[96] As she stood down, Alley informed the court that two more witnesses had arrived from Liverpool. However, when they saw Bellingham, they realised that he was not the man to whose derangement they had come to attest, and withdrew.[97] Mansfield then began his summing up, during the course of which he clarified the law: "The single question is whether at the time this act was committed, he possessed a sufficient degree of understanding to distinguish good from evil, right from wrong".[98] The judge advised the jury before they retired that the evidence showed Bellingham to be "in every respect a full and competent judge of all his actions".[99]

Verdict and sentence

The jury retired, and within 15 minutes returned with a guilty verdict. Bellingham appeared surprised but, from Thomas Hodgson's contemporary trial account, was calm, "with[out] any demonstrations of that concern which the awfulness of his situation was calculate to produce".[100] Asked by the court clerk if he had anything to say, he remained silent.[101]

The clerk then read the sentence, Hodgson records, "in a most solemn and affecting manner, which bathed many of the auditors in tears".[100] First, he damned the crime, "as odious and abominable in the eyes of God as it is hateful and abhorrent to the feelings of man".[100] He reminded the prisoner of the short time, "a very short time",[102] that remained for him to seek for mercy in another world, and then pronounced the sentence of death itself: "You shall be hanged by the neck until you be dead, your body to be dissected and anatomized".[103] The entire trial had lasted less than eight hours.[103]

Execution

Bellingham's execution was fixed for the morning of Monday 18 May.[104] The day before, he was visited by the Revd Daniel Wilson, curate at St John's Chapel, Bedford Row, a future Bishop of Calcutta, who hoped that Bellingham would show true repentance for his act.[105] The clergyman was disappointed, concluding that "a more dreadful instance of depravity and hardness of heart has surely never occurred".[106] Late on Sunday, Bellingham wrote a last letter to his wife, in which he appeared confident of his soul's destination: "Nine hours more will waft me to those happy shores where bliss is without alloy".[107]

Large crowds gathered outside Newgate on Monday; a force of troops stood by, since warnings had been received of a "Rescue Bellingham" movement.[108] The crowd was calm and restrained, as was Bellingham when he appeared at the scaffold shortly before 8 o'clock. Hodgson records that Bellingham mounted the steps "with the utmost celerity ... his tread was bold and firm ... no indication of trembling, faltering, or irresolution appeared".[109] Bellingham was then blindfolded, the rope fastened, and a final prayer was said by the chaplain. As the clock struck eight the trap door was released, and Bellingham dropped to his death. Cobbett, still incarcerated in Newgate, observed the crowd's reactions: "anxious looks ... half-horrified countenances ... mournful tears ... unanimous blessings".[110] In accordance with the court's sentence, the body was cut down and sent to St Bartholomew's Hospital for dissection.[111] In what the press described as "morbid sensationalism", Bellingham's clothes were sold for high prices to members of the public.[112]

Aftermath

_Prime_Minister_lived_here.jpg)

On 15 May, the House of Commons voted for the erection of a monument to the assassinated Prime Minister in Westminster Abbey. Later, memorials were placed in Lincoln's Inn, and within Perceval's Northampton constituency.[113]

On 8 June the Regent appointed Lord Liverpool to head a new Tory administration.[114] Despite their eulogies to their fallen leader, members of the new government soon began to distance themselves from his ministry. Many of the changes that Perceval had opposed were gradually introduced: greater press freedom, Catholic emancipation and parliamentary reform.[114] The Orders in Council were repealed on 23 June, but too late to avoid the declaration of war on Britain by the United States.[115] Lord Liverpool's government did not maintain Perceval's resolution in acting against the illegal slave trade, which began to flourish as the authorities looked the other way. Linklater estimates that around 40,000 slaves were illegally transported from Africa to the West Indies, because of lax enforcement of the law.[116]

Linklater cites Perceval's greatest achievement as his insistence on keeping Wellington's army in the field, a policy which helped to turn the tide in the Napoleonic Wars decisively in Britain's favour.[117] Despite this, with the passage of time Perceval's reputation faded; Charles Dickens considered him "a third-rate politician scarcely fit to carry Lord Chatham's crutch".[118] In due course, little but the fact of his assassination lingered in public memory. As the bicentenary of the shooting approached, Perceval was described in newspapers as "the prime minister that history forgot".[119][120]

The justice of Bellingham's conviction was first questioned by Brougham, who condemned the trial as "the greatest disgrace to English justice".[121] In a study published in 2004 the American academic Kathleen S. Goddard criticises the timing of the trial so soon after the act, when passions were running high. She also draws attention to the court's refusal to allow an adjournment that would permit the defence to contact possible witnesses.[122] There was, she maintains, insufficient evidence produced at the trial to determine the true state of Bellingham's sanity, and Mansfield's summing-up showed significant bias.[123] Bellingham's claim to have acted alone was accepted in court; Linklater's 2012 study posits that he could been an agent of other interests—perhaps Liverpool merchants, who bore the main brunt of Perceval's economic policies and had much to gain by his demise. Comments by a Liverpool newspaper, says Linklater, indicate that talk of assassination was common in the city. It remains unknown how Bellingham gained the funds to spend freely in the months preceding the assassination, when he was not apparently engaged in any business.[70] This conspiracy theory has not convinced other historians; the columnist Bruce Anderson points to the lack of any concrete evidence to support it.[120]

In the months immediately following her husband's execution, Mary Bellingham continued to live and work in Liverpool. By the end of 1812 her business had failed,[124] and thereafter her movements are obscure; she may have reverted to her maiden name.[125][124] In January 1815, Jane Perceval married Sir Henry William Carr; she died, aged 74, in 1844.[126]

In 1828, The Times reported that Cornish industrialist landowner, John Williams the Third (1753-1841) received a dream warning of Perceval's assassination on 2 or 3 May 1812, nearly ten days before the event, "correct in every detail".[127] Perceval himself had a series of dreams culminating on 10 May with one of his own death, which he had while spending the night at the house of the Earl of Harrowby. He told the Earl of his dream, and the Earl tried to persuade Perceval not to attend Parliament that day, but Perceval refused to be scared off by "a mere dream" and headed for Westminster on the afternoon of 11 May.[128]

A distant kinsman of the assassin, Henry Bellingham, became Conservative MP for North West Norfolk in 1983, and held junior office in the Conservative-Liberal coalition government of 2010–15.[129][130] When he temporarily lost his seat in 1997—he regained it in 2001—his narrow defeat was widely regarded as arising from the intervention of Roger Percival, the candidate for the Referendum Party whose votes largely came from disgruntled Conservatives. Despite the different spelling, media accounts asserted Percival's descent from the assassinated Prime Minister's family, and reported the defeat as a belated form of revenge.[129][131]

The greater part of the Palace of Westminster (Westminster Hall apart) that stood at the time of the assassination was destroyed by an accidental fire in 1834, following which the Houses were comprehensively rebuilt and expanded. In July 2014, a brass memorial plaque was unveiled in St Stephen's Hall, Houses of Parliament, close to the place where Perceval was killed. Michael Ellis, Conservative MP for Northampton North (part of Perceval's old Northampton constituency) had campaigned for the plaque after four patterned floor tiles that were said to mark the spot had been removed by workmen in a recent renovation.[132]

References

Citations

- ↑ Hanrahan 2012, pp. 19–22.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Jupp 2009.

- ↑ Linklater 2013, pp. 61–62.

- ↑ Linklater 2013, p. 63.

- 1 2 3 Hanrahan 2012, pp. 23–24.

- ↑ Hanrahan 2012, pp. 29–31.

- ↑ Linklater 2013, pp. 77–82.

- ↑ Harvey 1972, pp. 619–20.

- ↑ Hanrahan 2012, p. 48.

- 1 2 Hanrahan 2012, pp. 54–55.

- ↑ Uglow 2014, p. 489.

- ↑ Linklater 2013, pp. 84–85.

- 1 2 Linklater 2013, p. 90.

- ↑ Hanrahan 2012, pp. 56–57.

- ↑ Howard 1999.

- ↑ Uglow 2014, p. 499.

- ↑ Uglow 2014, pp. 444–45.

- 1 2 Hanrahan 2012, pp. 62–63.

- ↑ Hanrahan 2012, p. 64.

- ↑ Goddard 2004, p. 2.

- ↑ Hanrahan 2012, p. 56.

- ↑ Uglow 2014, p. 546.

- ↑ Uglow 2014, pp. 547–48.

- ↑ Linklater 2013, p. 87.

- ↑ Linklater 2013, pp. 161–62.

- ↑ Seaward 1994, p. 64.

- ↑ Uglow 2014, p. 560.

- ↑ Linklater 2013, pp. 8–10.

- 1 2 Linklater 2013, p. 101.

- ↑ Turner 2004.

- 1 2 Hanrahan 2012, pp. 68–70.

- ↑ Linklater 2013, pp. 109–10.

- ↑ Linklater 2013, pp. 53–54.

- ↑ Hanrahan 2012, pp. 70–72.

- ↑ Linklater 2013, p. 55.

- 1 2 Hodgson 1812, pp. 71–72.

- ↑ Linklater 2013, pp. 111–12.

- ↑ Hanrahan 2012, pp. 75–77.

- ↑ Linklater 2013, p. 56.

- ↑ Gillen 1972, p. 68.

- ↑ Gillen 1972, pp. 69–71.

- ↑ Hanrahan 2012, pp. 80–82.

- ↑ Gillen 1972, pp. 74–75.

- ↑ Hanrahan 2012, pp. 84–87.

- 1 2 Gillen 1972, pp. 76–78.

- ↑ Linklater 2013, p. 158.

- ↑ Pelham 1841, p. 529.

- 1 2 Goddard 2004, p. 8.

- ↑ Linklater 2013, pp. 211–12.

- ↑ Hanrahan 2012, p. 10.

- ↑ Gray 1963, p. 455.

- ↑ Gillen 1972, p. 87.

- ↑ Linklater 2013, pp. 216–17.

- ↑ Hanrahan 2012, pp. 96–97.

- ↑ Hanrahan 2012, pp. 9–10.

- ↑ Treherne 1909, pp. 193–94.

- ↑ Gillen 1972, pp. 3–4.

- ↑ Hanrahan 2012, pp. 11–13.

- ↑ Linklater 2013, p. 13.

- ↑ Gillen 1972, pp. 5–7.

- 1 2 Hanrahan 2012, p. 16.

- ↑ Hanrahan 2012, pp. 14–15.

- ↑ Gillen 1972, p. 13.

- ↑ Linklater 2013, pp. 20–21.

- ↑ Bryant 1952, p. 52.

- ↑ Uglow 2014, p. 581.

- ↑ Melikan 2008.

- ↑ Gillen 1972, p. 15.

- 1 2 3 Linklater 2013, pp. 22–24.

- 1 2 Linklater 2012.

- ↑ Treherne 1909, pp. 217–20.

- ↑ Gillen 1972, p. 29.

- ↑ Gray 1963, p. 27.

- ↑ Hanrahan 2012, pp. 99–101.

- ↑ Hanrahan 2012, p. 102.

- ↑ Linklater 2013, pp. 44–45.

- ↑ Linklater 2013, pp. 33–34.

- ↑ Linklater 2013, pp. 46–50.

- ↑ Gillen 1972, p. 23.

- ↑ Linklater 2013, pp. 97, 110–11.

- ↑ Gillen 1972, p. 40.

- 1 2 Hanrahan 2012, p. 110.

- 1 2 Hodgson 1812, p. 47.

- ↑ Hanrahan 2012, p. 113.

- ↑ Beattie 2013.

- ↑ Linklater 2013, p. 117.

- ↑ Hanrahan 2012, pp. 114–17.

- ↑ Hanrahan 2012, p. 119.

- ↑ Hodgson 1812, p. 55.

- ↑ Gillen 1972, p. 95.

- ↑ Linklater 2012, pp. 121–22.

- ↑ Goddard 2004, p. 13.

- ↑ Hanrahan 2012, p. 142.

- ↑ Hodgson 1812, p. 68.

- ↑ Hodgson 1812, pp. 69–74.

- ↑ Hanrahan 2012, pp. 150–57.

- ↑ Gillen 1972, p. 106.

- ↑ Goddard 2004, p. 12.

- ↑ Hodgson 1812, p. 69.

- 1 2 3 Hodgson 1812, pp. 89–90.

- ↑ Gillen 1972, pp. 108–09.

- ↑ Hodgson 1812, p. 91.

- 1 2 Hanrahan 2012, p. 164.

- ↑ Linklater 2013, p. 148.

- ↑ Hanrahan 2012, pp. 168–73.

- ↑ Wilson 1812, p. 30.

- ↑ Hanrahan 2012, p. 175.

- ↑ Hanrahan 2012, pp. 176–77.

- ↑ Hodgson 1812, pp. 96–97.

- ↑ Hanrahan 2012, p. 182.

- ↑ Linklater 2013, p. 229.

- ↑ Gillen 1972, p. 134.

- ↑ Treherne 1909, p. 222.

- 1 2 Hanrahan 2012, p. 207.

- ↑ Gillen 1972, p. 163.

- ↑ Linklater 2013, p. 230.

- ↑ Linklater 2013, pp. 88–89.

- ↑ Gray 1963, p. 468.

- ↑ Kennedy 2012.

- 1 2 Anderson 2012.

- ↑ Brougham 1871, p. 18.

- ↑ Goddard 2004, pp. 18–21.

- ↑ Goddard 2004, pp. 16–17.

- 1 2 Linklater 2012, pp. 232–33.

- ↑ Hanrahan 2012, p. 194.

- ↑ Hanrahan 2012, p. 195.

- ↑ "Remarkable Coincidence", 16 August 1828.

- ↑ "The wasted warning", 27 September 1980.

- 1 2 Parkinson 2009.

- ↑ Gov.uk 2015.

- ↑ Crick 2012.

- ↑ "Spencer Perceval: Plaque for assassinated prime minister", 21 July 2014.

Sources

Books and news articles

- Brougham, Henry (1871). The Life and Times of Henry, Lord Brougham. London: Blackwood. OCLC 831448086.

- Bryant, Arthur (1952). The Age of Elegance 1812–22. London: Collins. OCLC 851864668.

- Gillen, Mollie (1972). Assassination of the Prime Minister: The shocking death of Spencer Perceval. London: Sidgwick and Jackson. ISBN 978-0-283-97881-4.

- Gray, Denis (1963). Spencer Perceval. The Evangelical Prime Minister 1762–1812. Manchester: Manchester University Press. OCLC 612910771.

- Hanrahan, David C. (2012). The Assassination of the Prime Minister: John Bellingham and the Murder of Spencer Perceval. London: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7509-4401-4.

- Hodgson, Thomas (1812). A Full and Authentic Report of the Trial of John Bellingham, at the Sessions' House, in the Old Bailey, on Friday, May 15, 1812, for the Murder of the Right Honourable Spencer Perceval, Chancellor of the Exchequer, in the Lobby of the House Of Commons. London: Sherwood, Neely and Jones. OCLC 495783049.

- Linklater, Andro (2013). Why Spencer Perceval Had to Die: The Assassination of a British Prime Minister. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4088-3171-7.

- Pelham, Camden, ed. (1841). The Chronicles of Crime. London: Thomas Tegg. OCLC 268152.

- Seaward, Paul, ed. (1994). The Prime Ministers from Walpole to Macmillan. London: Dod's Parliamentary Companion Ltd. ISBN 978-0-905702-22-3.

- "Remarkable Coincidence". The Times (13673). 28 August 1828. p. 2.

- The Wasted Warning. Look and Learn. 27 September 1980. pp. 20–21.

- Treherne, Philip (1909). The Right Honourable Spencer Perceval. London: T. Fisher Unwin. OCLC 5825009.

- Uglow, Jenny (2014). In These Times. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-26953-2.

- Wilson, Daniel (1812). The Substance of a Conversation with John Bellingham. London: John Hatchard. OCLC 26167547.

Online

- Anderson, Bruce (28 April 2012). "Spencer Perceval deserves better from posterity". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

- Beattie, J.M. (2013). "Garrow, Sir William (1760–1840)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography online edition. Retrieved 23 September 2015. (subscription required)

- Crick, Michael (11 May 2012). "Minister admits family "shame" over Perceval assassination". Channel 4 News. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- Goddard, Kathleen S. (January 2004). "A Case of Injustice? The Trial of John Bellingham". The American Journal of Legal History. 46 (1): 1–25. doi:10.2307/3692416. JSTOR 3692416. (subscription required)

- Harvey, A.D. (December 1972). "The Ministry of All the Talents: The Whigs in Office, February 1806 to March 1807". The Historical Journal. 15 (4): 619–48. doi:10.1017/s0018246x00003484. JSTOR 2638036. (subscription required)

- "Henry Bellingham". Gov.uk. 2015. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

- Howard, Martin R. (18 December 1999). "Walcheren 1809: a medical catastrophe". The British Medical Journal. 319: 1642–45. doi:10.1136/bmj.319.7225.1642. PMC 1127097

. PMID 10600979.

. PMID 10600979. - Jupp, P.J. (2009). "Perceval, Spencer (1762–1812)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography online edition. Retrieved 23 September 2015. (subscription required)

- Kennedy, Maev (10 May 2012). "Spencer Perceval, the assassinated prime minister that history forgot". The Guardian. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

- Linklater, Andro (5 May 2012). "Target man". The Spectator. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

- Melikan, R.A. (2008). "Romilly, Sir Samuel (1757–1818)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography online edition. Retrieved 23 September 2015. (subscription required)

- Parkinson, Justin (26 November 2009). "The MP whose ancestor killed the prime minister". BBC News. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- "Spencer Perceval: Plaque for assassinated prime minister". BBC. 21 July 2014. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- Turner, Michael J. (2004). "Bellingham, John (1770–1812)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography online edition. Retrieved 23 September 2015. (subscription required)