Von Willebrand factor

| View/Edit Human | View/Edit Mouse |

Von Willebrand factor (vWF) (/ˌfʌnˈvɪlᵻbrɑːnt/) is a blood glycoprotein involved in hemostasis. It is deficient or defective in von Willebrand disease and is involved in a large number of other diseases, including thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, Heyde's syndrome, and possibly hemolytic-uremic syndrome.[3] Increased plasma levels in a large number of cardiovascular, neoplastic, and connective tissue diseases are presumed to arise from adverse changes to the endothelium, and may contribute to an increased risk of thrombosis.

Biochemistry

Synthesis

vWF is a large multimeric glycoprotein present in blood plasma and produced constitutively as ultra-large vWF in endothelium (in the Weibel-Palade bodies), megakaryocytes (α-granules of platelets), and subendothelial connective tissue.[3]

Structure

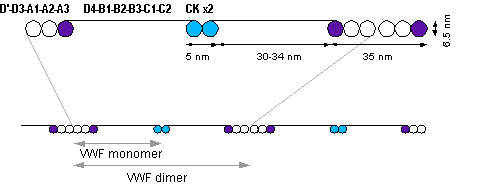

The basic vWF monomer is a 2050-amino acid protein. Every monomer contains a number of specific domains with a specific function; elements of note are:[3]

- the D'/D3 domain, which binds to factor VIII, (Von Willebrand factor type D domain)

- the A1 domain, which binds to:

- the A2 domain, which must partially unfold to expose the buried cleavage site for the specific ADAMTS13 protease that inactivates vWF by making much smaller multimers. The partial unfolding is affected by shear flow in the blood, by calcium binding, and by the lump of a sequence-adjacent "vicinal disulfide" at the A2-domain C-terminus.[4][5]

- the A3 domain, which binds to collagen (Von Willebrand factor type A domain)

- the C1 domain, in which the RGD motif binds to platelet integrin αIIbβ3 when this is activated (Von Willebrand factor type C domain)

- the "cysteine knot" domain (at the C-terminal end of the protein), which vWF shares with platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ) and β-human chorionic gonadotropin (βHCG, of pregnancy test fame). (Von Willebrand factor type C domain)

Monomers are subsequently N-glycosylated, arranged into dimers in the endoplasmic reticulum and into multimers in the Golgi apparatus by crosslinking of cysteine residues via disulfide bonds. With respect to the glycosylation, vWF is one of only a few proteins that carry ABO blood group system antigens.[3]

Multimers of vWF can be extremely large, >20,000 kDa, and consist of over 80 subunits of 250 kDa each. Only the large multimers are functional. Some cleavage products that result from vWF production are also secreted but probably serve no function.[3]

Function

Von Willebrand factor's primary function is binding to other proteins, in particular factor VIII, and it is important in platelet adhesion to wound sites.[3] It is not an enzyme and, thus, has no catalytic activity.

vWF binds to a number of cells and molecules. The most important ones are:[3]

- Factor VIII is bound to vWF while inactive in circulation; factor VIII degrades rapidly when not bound to vWF. Factor VIII is released from vWF by the action of thrombin.

- vWF binds to collagen, e.g., when it is exposed in endothelial cells due to damage occurring to the blood vessel. Endothelium also releases vWF which forms additional links between the platelets' glycoprotein Ib/IX/V and the collagen fibrils

- vWF binds to platelet gpIb when it forms a complex with gpIX and gpV; this binding occurs under all circumstances, but is most efficient under high shear stress (i.e., rapid blood flow in narrow blood vessels, see below).

- vWF binds to other platelet receptors when they are activated, e.g., by thrombin (i.e., when coagulation has been stimulated).

vWF plays a major role in blood coagulation. Therefore, vWF deficiency or dysfunction (von Willebrand disease) leads to a bleeding tendency, which is most apparent in tissues having high blood flow shear in narrow vessels. From studies it appears that vWF uncoils under these circumstances, decelerating passing platelets.[3] Calcium enhances the refolding rate of vWF A2 domain, allowing the protein to act as a shear force sensor.[4]

Catabolism

The biological breakdown (catabolism) of vWF is largely mediated by the enzyme ADAMTS13 (acronym of "a disintegrin-like and metalloprotease with thrombospondin type 1 motif no. 13"). It is a metalloproteinase that cleaves vWF between tyrosine at position 842 and methionine at position 843 (or 1605–1606 of the gene) in the A2 domain. This breaks down the multimers into smaller units, which are degraded by other peptidases.[6]

Role in disease

Hereditary or acquired defects of vWF lead to von Willebrand disease (vWD), a bleeding diathesis of the skin and mucous membranes, causing nosebleeds, menorrhagia, and gastrointestinal bleeding. The point at which the mutation occurs determines the severity of the bleeding diathesis. There are three types (I, II and III), and type II is further divided in several subtypes. Treatment depends on the nature of the abnormality and the severity of the symptoms.[7] Most cases of vWD are hereditary, but abnormalities of vWF may be acquired; aortic valve stenosis, for instance, has been linked to vWD type IIA, causing gastrointestinal bleeding - an association known as Heyde's syndrome.[8]

In thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) and hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS), ADAMTS13 either is deficient or has been inhibited by antibodies directed at the enzyme. This leads to decreased breakdown of the ultra-large multimers of vWF and microangiopathic hemolytic anemia with deposition of fibrin and platelets in small vessels, and capillary necrosis. In TTP, the organ most obviously affected is the brain; in HUS, the kidney.[9]

Higher levels of vWF are more common among people that have had ischemic stroke (from blood-clotting) for the first time. Occurrence is not affected by ADAMTS13, and the only significant genetic factor is the person's blood group.High plasma vWF levels were found to be an independent predictor of major bleeding in anticoagulated atrial fibrillation patients.[10]

History

vWF is named after Dr. Erik von Willebrand (1870–1949), a Finnish doctor who in 1924 first described a hereditary bleeding disorder in families from the Åland islands, who had a tendency for cutaneous and mucosal bleeding, including menorrhagia. Although von Willebrand could not identify the definite cause, he distinguished von Willebrand disease (vWD) from hemophilia and other forms of bleeding diathesis.[11]

In the 1950s, vWD was shown to be caused by a plasma factor deficiency (instead of being caused by platelet disorders), and, in the 1970s, the vWF protein was purified.[3]

Interactions

Von Willebrand factor has been shown to interact with Collagen, type I, alpha 1.[12]

Recently, It has been reported that the cooperation and interactions within the Von Willebrand factors enhances the adsorption probability in the primary hameostasis. Such cooperation is proven by calculating the adsorption probability of flowing vWF once it crosses another adsorbed one. Such cooperation is held within a wide range of shear rates.[13]

See also

References

- ↑ "Human PubMed Reference:".

- ↑ "Mouse PubMed Reference:".

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Sadler JE (1998). "Biochemistry and genetics of von Willebrand factor". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 67: 395–424. doi:10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.395. PMID 9759493.

- 1 2 Jakobi AJ, Mashaghi A, Tans SJ, Huizinga EG. Calcium modulates force sensing by the von Willebrand factor A2 domain. Blood. 2011 April 28, 117:17.Nature Commun. 2011 Jul 12;2:385.

- ↑ Luken BM, Winn LY, Emsley J, Lane DA, Crawley JT (June 2010). "The importance of vicinal cysteines, C1669 and C1670, for von Willebrand factor A2 domain function". Blood. 115 (23): 4910–3. doi:10.1182/blood-2009-12-257949. PMID 20354169.

- ↑ Levy GG, Motto DG, Ginsburg D (July 2005). "ADAMTS13 turns 3". Blood. 106 (1): 11–7. doi:10.1182/blood-2004-10-4097. PMID 15774620.

- ↑ Sadler JE, Budde U, Eikenboom JC, Favaloro EJ, Hill FG, Holmberg L, Ingerslev J, Lee CA, Lillicrap D, Mannucci PM, Mazurier C, Meyer D, Nichols WL, Nishino M, Peake IR, Rodeghiero F, Schneppenheim R, Ruggeri ZM, Srivastava A, Montgomery RR, Federici AB (October 2006). "Update on the pathophysiology and classification of von Willebrand disease: a report of the Subcommittee on von Willebrand Factor". Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 4 (10): 2103–14. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.02146.x. PMID 16889557.

- ↑ Vincentelli A, Susen S, Le Tourneau T, Six I, Fabre O, Juthier F, Bauters A, Decoene C, Goudemand J, Prat A, Jude B (July 2003). "Acquired von Willebrand syndrome in aortic stenosis". The New England Journal of Medicine. 349 (4): 343–9. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa022831. PMID 12878741.

- ↑ Moake JL (January 2004). "von Willebrand factor, ADAMTS-13, and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura". Seminars in Hematology. 41 (1): 4–14. doi:10.1053/j.seminhematol.2003.10.003. PMID 14727254.

- ↑ Roldán V, Marín F, Muiña B, Torregrosa JM, Hernández-Romero D, Valdés M, Vicente V, Lip GY (June 2011). "Plasma von Willebrand factor levels are an independent risk factor for adverse events including mortality and major bleeding in anticoagulated atrial fibrillation patients". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 57 (25): 2496–504. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2010.12.033. PMID 21497043.

- ↑ von Willebrand EA (1926). "Hereditär pseudohemofili". Fin Läkaresällsk Handl. 68: 87–112. Reproduced in Von Willebrand EA (May 1999). "Hereditary pseudohaemophilia". Haemophilia. 5 (3): 223–31; discussion 222. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2516.1999.00302.x. PMID 10444294.

- ↑ Pareti FI, Fujimura Y, Dent JA, Holland LZ, Zimmerman TS, Ruggeri ZM (November 1986). "Isolation and characterization of a collagen binding domain in human von Willebrand factor". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 261 (32): 15310–5. PMID 3490481.

- ↑ Heidari M, Mehrbod M, Ejtehadi MR, Mofrad MR (August 2015). "Cooperation within von Willebrand factors enhances adsorption mechanism". Journal of the Royal Society, Interface. 12 (109): 20150334. doi:10.1098/rsif.2015.0334. PMC 4535404

. PMID 26179989.

. PMID 26179989.