Bucket shop (stock market)

As defined by the U.S. Supreme Court, a bucket shop is "[a]n establishment, nominally for the transaction of a stock exchange business, or business of similar character, but really for the registration of bets, or wagers, usually for small amounts, on the rise or fall of the prices of stocks, grain, oil, etc., there being no transfer or delivery of the stock or commodities nominally dealt in."[1] People often mistakenly interchange the words bucket shop and boiler room, but there is actually a significant difference. A boiler room has been defined as a place where high-pressure salespeople use banks of telephones to call lists of potential investors (known as "sucker lists") in order to peddle speculative, even fraudulent, securities. However, with a bucket shop, it could be better thought of as a place where people go to make "side bets" – similar to a bookie.

"Bucket shop" is a defined term under the criminal law of many states in the United States that make it a crime to operate a bucket shop.[2] Typically the criminal law definition refers to an operation in which the customer is sold what is supposed to be a derivative interest in a security or commodity future, but there is no transaction made on any exchange. The transaction goes "in the bucket" and is never executed. Without an actual underlying transaction, the customer is betting against the bucket shop operator, not participating in the market. Alternatively, the bucket shop operator "literally 'plays the bank,' as in a gambling house, against the customer." [3] Operating a bucket shop in the United States would also likely involve violations of several provisions of federal securities or commodity futures laws.[4]

A person who engages in the practice is referred to as a bucketeer and the practice is sometimes referred to as bucketeering.

History in the United States

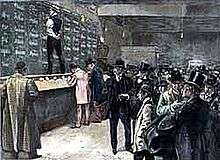

Bucket shops specializing in stocks and commodity futures flourished in the United States from the 1870s until the 1920s.[5] Edwin Lefèvre, who is believed to have been writing on behalf of Jesse Lauriston Livermore, describes the operations of bucket shops in the 1890s in detail.[6] In the United States, the traditional pseudo-brokerage bucket shops came under increasing legal assault in the early 1900s, and were effectively eliminated before the 1920s.[7] However, the term came to apply to other types of scams, some of which are still practiced. They were typically small store front operations that catered to the small investor, where speculators could bet on price fluctuations during market hours. However, no actual shares were bought or sold: all trading was between the bucket shop and its clients. The bucket shop made its profit from commissions, and also profited when share prices went against the client.

The terms of trade were different for each bucket shop, but bucket shops typically catered to customers who traded on thin margins, even as low as 1%. Most bucket shops refused to make margin calls, so that if the stock price fell even momentarily to the limit of the client's margin, the client would lose his entire investment.

The highly leveraged use of margins theoretically gave the speculators equally large upside potential. However, if a bucket shop held a large position on a stock, it might sell the stock on the real stock exchange, causing the price on the ticker tape to momentarily move down enough to wipe out its client's margins, and the bucket shop could take 100% of their investments.[8]

They were made illegal after they were cited as a major contributor to the two stock market crashes in the early 1900s.

Origin of the term

The origin of the term bucket shop has nothing to do with financial markets, as the term originated from England in the 1820s. During the 1820s, street urchins drained beer kegs which were discarded from public houses. The street urchins would take the dregs to an abandoned shop and drink them. This practice became known as bucketing, and the location at which they drained the kegs became known as a bucket shop. The idea was transferred to illegal brokers because they too sought to profit from sources too small or too unreliable for legitimate brokers to handle.[9]

The term bucket shop came to apply to low-class pseudo stock brokerages that did not execute trades.[10][11]

See also

- Boiler room (business)

- Forex scam

- Binary option

- Pump and dump

- Panic of 1907

- Guinness share-trading fraud

References

- ↑ Gatewood v. North Carolina, 27 S.Ct 167, 168 (1906).

- ↑ For example, see California's definition, Washington State's definition, Pennsylvania's definition, or Mississippi's definition Archived September 27, 2007, at the Wayback Machine..

- ↑ "Bucket Shop Secrets," New York Times, July 9, 1922. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F00F17F83B5D14738DDDA00894DF405B828EF1D3

- ↑ http://caselaw.lp.findlaw.com/cgi-bin/getcase.pl?court=4th&navby=docket&no=001488p See, for example, CFTC v. Baragosh (currency futures bucket shop)

- ↑ David Hochfelder | "Where the Common People Could Speculate": The Ticker, Bucket Shops, and the Origins of Popular Participation in Financial Markets, 1880–1920 | The Journal of American History, 93.2 | The History Cooperative Archived September 4, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Edwin Lefèvre (1923). Reminiscences of a Stock Operator.

- ↑ YALE M. BRAUNSTEIN, "The Role of Information Failures in the Financial Meltdown" Archived December 22, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. SCHOOL OF INFORMATION, UC BERKELEY, SUMMER 2009

- ↑ Edwin Lefèvre(1923) Reminiscences of a Stock Operator, reprinted 1968, New York: Simon & Schuster. (the book is regarded as a roman à clef of the life of actual stock operator Jesse Livermore).

- ↑ John Hill, Gold Bricks of Speculation 39 (Chicago Lincoln Book Concern, 1904).

- ↑ Ann Fabian (1999) Card Sharps and Bucket Shops, New York: Routledge, p.189.

- ↑ Hill, John Jr., Gold Bricks of Speculation, (Chicago, Il.,: Lincoln Book Concern, 1904) p.39. Quoted in Markham, Jerry The History of Commodity Futures Trading and its Regulation, (New York, Praeger, 1987) Chapt. 1 n.13.

External links

-

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Bucketshop". Encyclopædia Britannica. 4 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Bucketshop". Encyclopædia Britannica. 4 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.