Cardinal vowels

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

Cardinal vowels are a set of reference vowels used by phoneticians in describing the sounds of languages. For instance, the vowel of the English word "feet" can be described with reference to cardinal vowel 1, [i], which is the cardinal vowel closest to it. It is often stated that to be able to use the cardinal vowel system effectively one must undergo training with an expert phonetician, working both on the recognition and the production of the vowels. Daniel Jones wrote "The values of cardinal vowels cannot be learnt from written descriptions; they should be learnt by oral instruction from a teacher who knows them".[1]

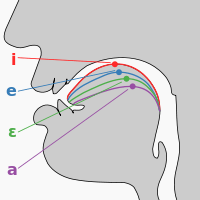

A cardinal vowel is a vowel sound produced when the tongue is in an extreme position, either front or back, high or low. The current system was systematised by Daniel Jones in the early 20th century,[2] though the idea goes back to earlier phoneticians, notably Ellis[3] and Bell.[4]

Cardinal vowels are not vowels of any particular language, but a measuring system. However, some languages contain vowel or vowels that are close to the cardinal vowel(s).[5] An example of such language is Ngwe, which is spoken in West Africa. It has been cited as a language with a vowel system that has 8 vowels which are rather similar to the 8 primary cardinal vowels (Ladefoged 1971:67).

Three of the cardinal vowels—[i], [ɑ] and [u]—have articulatory definitions. The vowel [i] is produced with the tongue as far forward and as high in the mouth as is possible (without producing friction), with spread lips. The vowel [u] is produced with the tongue as far back and as high in the mouth as is possible, with protruded lips. This sound can be approximated by adopting the posture to whistle a very low note, or to blow out a candle. And [ɑ] is produced with the tongue as low and as far back in the mouth as possible.

The other vowels are 'auditorily equidistant' between these three 'corner vowels', at four degrees of aperture or 'height': close (high tongue position), close-mid, open-mid, and open (low tongue position).

These degrees of aperture plus the front-back distinction define 8 reference points on a mixture of articulatory and auditory criteria. These eight vowels are known as the eight 'primary cardinal vowels', and vowels like these are common in the world's languages.

The lip positions can be reversed with the lip position for the corresponding vowel on the opposite side of the front-back dimension, so that e.g. Cardinal 1 can be produced with rounding somewhat similar to that of Cardinal 8 (though normally compressed rather than protruded); these are known as 'secondary cardinal vowels'. Sounds such as these are claimed to be less common in the world's languages.[6] Other vowel sounds are also recognised on the vowel chart of the International Phonetic Alphabet.

Table of cardinal vowels

| cardinal | IPA | description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | [i] | close front unrounded vowel |

| 2 | [e] | close-mid front unrounded vowel |

| 3 | [ɛ] | open-mid front unrounded vowel |

| 4 | [a] | open front unrounded vowel |

| 5 | [ɑ] | open back unrounded vowel |

| 6 | [ɔ] | open-mid back rounded vowel |

| 7 | [o] | close-mid back rounded vowel |

| 8 | [u] | close back rounded vowel |

| 9 | [y] | close front rounded vowel |

| 10 | [ø] | close-mid front rounded vowel |

| 11 | [œ] | open-mid front rounded vowel |

| 12 | [ɶ] | open front rounded vowel |

| 13 | [ɒ] | open back rounded vowel |

| 14 | [ʌ] | open-mid back unrounded vowel |

| 15 | [ɤ] | close-mid back unrounded vowel |

| 16 | [o] | close back unrounded vowel |

| 17 | [ɨ] | Close central unrounded vowel |

| 18 | [ʉ] | Close central rounded vowel |

In the International Phonetic Association's number chart, the cardinal vowels have the same numbers used above, but added to 300.

Limits on the accuracy of the system

The usual explanation of the cardinal vowel system implies that the competent user can reliably distinguish between sixteen Primary and Secondary vowels plus a small number of central vowels. The provision of diacritics by the International Phonetic Association further implies that intermediate values may also be reliably recognized, so that a phonetician might be able to produce and recognize not only a close-mid front unrounded vowel [e] and an open-mid front unrounded vowel [ɛ] but also a mid front unrounded vowel [e̞], a centralized mid front unrounded vowel [ë], and so on. This suggests a range of vowels nearer to forty or fifty than to twenty in number. Empirical evidence for this ability in trained phoneticians is hard to come by.

Ladefoged, in a series of pioneering experiments published in the 1950s and 60s, studied how trained phoneticians coped with the vowels of a dialect of Scots Gaelic. He asked eighteen phoneticians to listen to a recording of ten words spoken by a native speaker of Gaelic and to place the vowels on a cardinal vowel quadrilateral. He then studied the degree of agreement or disagreement among the phoneticians. Ladefoged himself drew attention to the fact that the phoneticians who were trained in the British tradition established by Daniel Jones were closer to each other in their judgments than those who had not had this training. However, the most striking result is the great divergence of judgments among all the listeners regarding vowels that were distant from Cardinal values.[7]

See also

- list of phonetics topics

- audio demonstrations of cardinal vowels as spoken by Daniel Jones at age 75

Bibliography

- Ladefoged, Peter. (1971). Preliminaries to linguistic phonetics. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

References

- ↑ Jones, Daniel (1967). An Outline of English Phonetics (9th ed.). Cambridge: Heffer. p. 34.

- ↑ Jones, Daniel (1917). An English Pronouncing Dictionary. London: Dent.

- ↑ Ellis, A.J. (1845). The Alphabet of Nature. Bath.

- ↑ Bell, A.M. (1867). Visible Speech. London.

- ↑ Ashby, Patricia (2011), Understanding Phonetics, Understanding Language series, Routledge, p. 85, ISBN 978-0340928271

- ↑ Ladefoged, P.; Maddieson, I. (1996). The Sounds of the World's Languages. Blackwell. p. 292. ISBN 0-631-19815-6.

- ↑ Ladefoged, P. (1967). Three Areas of Experimental Phonetics. Oxford University Press. pp. 132–142. See especially Figure 47 on p. 135