Chinese home run

In baseball, a Chinese home run, also a Chinese homer, Harlem home run,[1] or Pekinese poke,[2] is a derogatory and archaic term for a hit that just barely clears the outfield fence at its closest distance to home plate, essentially the shortest home run possible in the ballpark in question, particularly if the park is known to have an atypically short fence to begin with. The term was most commonly used in reference to home runs hit along the right field foul line at the Polo Grounds, home of the New York Giants, where that distance was short even by contemporary standards. When the Giants moved to San Francisco in 1958, the Los Angeles Coliseum, temporary home of the newly relocated Los Angeles Dodgers, took over the reputation for four seasons until the team took up residence in its permanent home at Dodger Stadium in 1962. Following two seasons of use by the expansion New York Mets in the early 1960s, the Polo Grounds were demolished, and the term gradually dropped out of use.[2]

The exact origins of the term are unknown, but it is believed to have reflected an early 20th-century perception that Chinese immigrants did the menial labor they were consigned to with a bare minimum of adequacy, and were content with minimal reward for it. It has been suggested that it originated with a Tad Dorgan cartoon, but that has not been proven. In the 1950s, an extended take on the term in the New York Daily News led to a petition in the Chinese-American community calling on sportswriters to stop using it.[3] This perception of ethnic insensitivity has further contributed to its disuse today.[4]

It has been used to disparage the hit and the batter who made it, since it implies minimal effort on his part. The Giants' Mel Ott was frequently cited for this, since he was able to hit many such home runs in the Polo Grounds during his career and his physique and unusual batting stance were not those usually associated with a power hitter. The hit most frequently recalled as a Chinese home run was the three-run pinch hit walk-off shot by Dusty Rhodes that won the first game of the 1954 World Series for the Giants on their way to a sweep of the Cleveland Indians.

A secondary meaning, which continues today, is of a foul ball that travels high and far, often behind home plate. However, this appears to be confined to sandlot and high-school games in New England. Research into this usage suggests that it may not, in fact, have had anything initially to do with Chinese people, but is instead a corruption of "Chaney's home run", from a foul by a player of that name which supposedly won a game when the ball, the only one remaining, could not be found.[2]

Etymology

| Look up Chinese home run in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

As early as the late 19th century, the baseball community had recognized that parks with shorter distances to the foul poles and back fence allowed for home runs that were thought of as undeserved or unearned, since fly balls of the same distance hit closer to or in center field could easily result in outs when fielders caught them. In 1896 Jim Nolan of the Daily News of Galveston, Texas, reporting on the expansion of the local ballpark, wrote: "The enlarged size of the grounds will enable the outfielders to cover more ground and take in fly balls that went for cheap home runs before. Batsmen will have to earn their triples and home runs hereafter".[5] In 2010 Jonathan Lighter, a member of the American Dialect Society's listserv, found the earliest use of the term "Chinese home run" for that type of hit in a Charleroi, Pennsylvania, newspaper's account of a Philadelphia Phillies game against the Pittsburgh Pirates: "The Phillies went into a deadlock on Cy's Chinese homer only to see the Buccos hammer over four runs a little later."[6]

This predates by three years the earliest use that Paul Dickson found when researching his The Dickson Baseball Dictionary. In a 1930 Washington Post story, writer Brian Bell quoted Dan Howley, then manager of the Cincinnati Reds, defending the hitting prowess of Harry Heilmann, who was then finishing his career under Howley. "[They] were real home runs", Howley said, pointing out how far from the field they had landed. "They were not Chinese home runs in that short bleacher at right", referring to the back fence on the foul line at the Polo Grounds, a mere 258 feet (79 m) from home.[2]

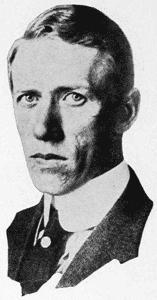

Dickson reiterated the results of two attempts in the 1950s to determine the term's origin, following its widespread use in stories. After Rhodes' home run, Joseph Sheehan of The New York Times took the first swing. His research took him to Garry Schumacher, a former baseball writer then working as a Giants' executive, who had been known for creating some baseball terms that went into wide use. Schumacher told him that he believed Tad Dorgan, a cartoonist popular in the early decades of the 20th century, had introduced it, probably in one of his widely read Indoor Sports panels.[2] It has, however, been suggested that Dorgan disliked the Giants and their manager, John McGraw, which may have also given him a reason to coin a disparaging term for short home runs.[7]

During the 1910s, the peak period of Dorgan's cartooning, there was an ongoing debate over the Chinese Exclusion Act, the first immigration law in U.S. history to bar entry to the country on the basis of ethnicity or national origin. Chinese immigrants who had entered prior to its 1882 passage remained, however, and were often hired as "coolies", doing menial labor for low pay. "The idea was to express a cheap home run as Chinese then represented what was cheap, such as their labor", lexicographer David Shulman told Sheehan. This was in keeping with a bevy of other contemporary such usages, such as calling a Ford automobile a "Chinese Rolls-Royce". Sheehan did not think that Dorgan, known for the gentleness of his satire, had meant it to be insulting, especially since he had two adopted sons from China.[2]

Four years later, when the Giants moved to San Francisco and left the Polo Grounds vacant, J. G. Taylor Spink, publisher of The Sporting News, made another attempt to find the source of the term. He came to the same conclusion as Sheehan, that it had originated with Dorgan and the association of the Chinese immigrants with cheap labor. However, his article was reprinted in the Los Angeles Times, and readers there wrote in with alternative suggestions afterwards.[2]

One was from Travis McGregor, a retired San Francisco sportswriter. In his recollection, the term had been in use on the West Coast in the years just before World War I. He attributed it to a joke derived from an aspiring Chinese-American sportswriter covering minor league games in the Pacific Coast League, whom the typists at newspapers simply credited as "Mike Murphy" since they couldn't properly transcribe his name. "He had a keen sense of humor, a degree from Stanford and a great yen to be a newspaperman", McGregor wrote in his own letter to The Sporting News. As a result of his education, he spoke with no accent, but still used affected syntax. "He was a one-man show at baseball games ... for two or three seasons, an Oriental Fred Allen", according to McGregor. Once, he recalled, Murphy described one batter as "wave at ball like Mandarin with fan".[2]

This phrase stuck in the minds of the other sportswriters in attendance and, McGregor suggested, it spread among all the league's writers, becoming a catch phrase. "The old Oakland park's short fence caught the most of it from Mike, and his 'Mandarin fan' waving balls out of the park were knocked back to 'Chinese homers'", said McGregor. A number of Murphy's comments were adapted into cartoons by Dorgan, a native of San Francisco, and from there the term migrated into print. McGregor believed that either Ed Hughes or Harry Smith of the San Francisco Chronicle were the first to do so, and better-known writers like Ring Lardner and Damon Runyon may have picked it up from them and popularized it nationwide.[2]

Sportswriters extended on the idea. Shulman wrote in 1930 of hearing them talk about short pop flies as "Chinese line drives".[2] Texas leaguers, or high bloop singles that fell between the infielders and outfielders, hit in Pacific Coast League games were likewise called "Japanese line drives".[8]

There have been other theories to explain how home runs that barely cleared the fence came to be called Chinese by association. Dan Schlossberg, a veteran Associated Press baseball writer, accepts the Dorgan story but also reports that Bill McGeehan, then sports editor of the New York Tribune, had in 1920 likened the right field fence at the Polo Grounds to the Great Wall of China: "thick, low, and not very formidable", suggesting that that may also have had something to do with the term's coinage.[7] Russ Hodges, who called Giants games on the radio in both New York and San Francisco, told the latter city's Call-Bulletin in 1958 that the term came into use from the supposed tendency of Chinese gamblers watching games at the Polo Grounds in the early 20th century to cluster in seats next to the left field foul pole. "Any hit that went out at that point", he explained, "was followed by cries of 'There goes one for the Chinese'".[2]

Another Sporting News columnist, Joe Falls, devoted a column to the term and solicited theories of its origin from readers. Some suggested that it had something to do with the "short jump" in Chinese checkers, or that since Chinese people were generally short, that short home runs would be named after them. Another reader claimed that the term arose because the outfield seats in the Polo Grounds supposedly stuck out in ways that suggested a pagoda.[2]

History

The term appears to have caught on quickly in baseball throughout the 1920s. By the 1950s, it was still in use but its connotations were no longer clear, and its use after one notoriously short home run that won a World Series game sparked a protest. After the 1964 demolition of the Polo Grounds, with its notoriously short right field fence, the term largely fell from use.

1920s–1954: Mel Ott

After establishing itself in baseball's argot, "Chinese home run" continued to be used, even while most of the other derogatory terms related to the Chinese fell from use as American public opinion began to see the Chinese people in a more sympathetic light due to China's struggles against Japanese domination during the 1930s, struggles that led to the U.S. and China becoming allies during World War II. Within baseball it was frequently associated with the Giants and the Polo Grounds, with its short right-field fence. One Giant in particular, outfielder Mel Ott, was sometimes described as the master of the Chinese home run, since he hit many of his 511 career home runs (a National League record at the time of his retirement) to right field in the team's home stadium (although often to the upper deck) during his 1926–45 playing career.[9]

The association likely developed because in addition to not having the physique commonly associated with power hitters, Ott used an unusual batting technique. The 5-foot-9-inch (1.75 m) outfielder preceded his swings by dropping his hands, lifting his front leg and stepping forward on it as the pitch came. Since that defied accepted baseball wisdom about how to hit the long ball, it was assumed that Ott was focusing on the short right field fence, and sportswriters often kidded him about this. Ott, who worked on his technique extensively, would usually respond by pointing out that if it was so easy, other batters in the league should have been able to hit even more of those home runs when visiting the Giants. It has also been pointed out that Ott's best-known home run, which won his team the 1933 World Series from the Washington Senators, was hit in Griffith Stadium, not the Polo Grounds, and over a longer fence.[9]

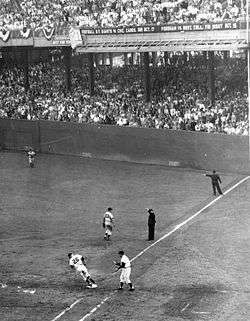

1954–57: Dusty Rhodes

While Bobby Thomson's 1951 pennant-clinching "Shot Heard 'Round The World" has sometimes been described as a Chinese home run,[2] the best-known such hit by a Giant in the Polo Grounds also won an extra-inning World Series game, and may have proved decisive in eventually winning that series for the Giants. In the 10th inning of Game 1 of the 1954 World Series against the heavily favored Cleveland Indians, Giants' manager Leo Durocher, on a hunch, sent in Dusty Rhodes to pinch hit for Monte Irvin. The left-handed Rhodes hit a walk-off home run just over the right field fence, giving the Giants the three runs they needed to win the game.[9]

The extensive media coverage led to discussions of both the term, such as Sheehan's in the Times, and Chinese home runs themselves. Since the late 1940s, there had been complaints from older fans that they were part of the decline of the game. "Ballplayers played ball in those days", said a writer in a 1948 column in the Lowell, Massachusetts, Sun. "Now they pop a Chinese home run into an overhanging balcony and the crowd thinks it's wonderful".[6] Two years later, Richard Maney included the Chinese home run among the failings of the postwar game in a Times piece.[10]

That game is chiefly remembered today for Willie Mays' catch of a Vic Wertz fly to deep center in the eighth inning, which broke up an Indians' rally that might otherwise have led to them winning the game. It had happened because of the 483-foot (147 m) distance of the Polo Grounds' fences in that area, its other peculiarity, which offset the advantage to hitters of its short right-field fence. The Indians attributed their upset loss to the park's unusual dimensions. "The longest out and the shortest home run of the season beat us, that's all", Indians manager Al López told the Washington Post. The team was unable to recover psychologically,[11] and the Giants swept them three games later.[12]

Sportswriters riffed on the "Chinese" aspect of Rhodes' home run. One newspaper's photographer posed him reading a Chinese newspaper, apparently looking for an account of his hit.[13] The Times called it "more Chinese than chow mein and just as Chinese as Shanghai and Peiping".[14]

Dick Young extended the trope in his Daily News coverage:[3]

The story of the Giants' 5–2 win over Cleveland in yesterday's World Series opener should be written vertically, from top to bottom ... in Chinese hieroglyphics. It was won on a 10th inning homer that was not only sudden death but pure murder ... right out of a Charlie Chan yarn. Ming Toy Rhodes, sometimes called Dusty by his Occidental friends, was honorable person who, as a pinch hitter, delivered miserable bundle of wet wash to first row in rightfield of Polo Grounds, some 259 1⁄2 feet down the road from the laundry.

This unrestrained use of Chinese stereotypes, both in content and phrasing, drew a protest. Shavey Lee, long considered the unofficial "mayor" of New York's Chinatown, collected signatures on a petition (in Chinese[15]) from himself and other members of the city's Chinese American community, demanding not just Young but all sportswriters stop using the term, and presented it to the Giants' secretary Eddie Brannick.[3] "It isn't the fault of the Chinese if you have a 258-foot fence", he wrote. "Why should we be blamed all the time? What makes a cheesy home run a Chinese home run?"[3]

After Brannick posted it on the wall of the team's press room, Lee's petition earned him congratulatory letters from Chinese Americans all over the country, and became national news, earning time on the television series What's the Story. Jack Orr, a Sporting News writer, went to Lee's restaurant and told him he was right to object. "Writers shouldn't be using that term", he said. "But what took you so long to get around to protesting?"[3] Two years later, another New York sportswriter, Jimmy Cannon, noted when defining "Chinese home run" in a glossary of baseball terms he wrote for Baseball Digest that it "would probably be called something else if the Chinese had more influence".[2]

The Giants moved from the Polo Grounds to San Francisco at the end of the 1957 season. Chinese home runs were once again a subject of discussion at the end of the season and afterwards, with many writers remembering short shots like Thomson's and Rhodes' as a quirk of the former stadium now lost to baseball. Writing in the Times as spring training was underway, Gay Talese wrote that Giants' players in their new home missed the "cheap (or Chinese) home runs ... legal nonetheless".[16]

1958–61: Los Angeles Coliseum

Another park quickly took over the Polo Grounds' reputation for Chinese home runs. New York City's other National League team, the Brooklyn Dodgers, had also moved to the West Coast for the 1958 season, where they played their first home games in the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum. Built for the 1932 Olympics, it had mainly been used for football since then. Its field was well-suited for that sport and the track and field events it had been designed for, but putting a baseball diamond in it was awkward.[17] The left field pole was just 251 feet (77 m) from the plate, even shorter than right had been at the Polo Grounds, and it was much more likely that balls would be hit there due to the majority of batters being right-handed. Before the regular season began, players from other teams were complaining about it.[18]

Giants' pitcher Johnny Antonelli called it a "farce". Warren Spahn, ace for the defending World Series champion Milwaukee Braves, suggested that a rule be established requiring that all fences be at least 300 feet (91 m) from the plate.[18] Owner Walter O'Malley ordered that a 40-foot (12 m) wire mesh screen be put up behind the left field fence. "We don't want to acquire a reputation for Chinese home runs", he said.[19] Sports media, particularly back in New York, charged that O'Malley was destroying the game for the sake of ticket sales. Sports Illustrated titled a critical editorial "Every Sixth Hit a Homer!", expressing concern that Babe Ruth's record of 60 home runs during a season might easily fall to a less worthy hitter in the coming season due to the Dodgers' short fence.[20] An Associated Press (AP) poll of baseball writers found that a majority believed that any home run records set mainly in the Coliseum should carry an asterisk.[17]

As had happened with Rhodes' home run four years earlier, the Chinese-themed joking around the short fence continued. The screen was called the "Chinese screen" or the "Great Wall of China",[17] and the Coliseum as a whole became known as "O'Malley's Chinese Theatre",[20] "The House that Charlie Chan Built",[21] or even, in one Willard Mullin cartoon, "Flung Wong O'Malley's Little Joss House in Los Angeles".[2] Even The Sporting News, bucking the preseason trend by editorializing it was too early to say whether the short wall would adversely affect the game, felt compelled to put on the cover of that issue (which also included Spink's etymological investigation) a cartoon showing an outsized Chinese coolie hanging over the Coliseum's back fence.[22][Note 1] The Chinese American community in the Los Angeles area made its objections known.[21]

At first the worst fears of the media seemed to be justified. In the first week of play at the Coliseum, 24 home runs were hit, most of them over the left field fence and screen. Chicago Cubs outfielder Lee Walls, not especially distinguished as a hitter, was responsible for three of them — in a single game. Commissioner Ford Frick, who had defended the Coliseum's dimensions during the preseason, quickly proposed that a second, 60-foot (18 m) mesh screen be established in the stands at 333 feet (101 m) from the plate, with any balls that fell between the two a ground rule double; however, that turned to be impossible under earthquake-safety provisions of the Los Angeles building code.[18]

Pitchers eventually learned to adjust. They threw outside to right-handed hitters, requiring them to pull hard for the left-field fence, and as at the Polo Grounds, a deep fence in right center (444 feet (135 m)) challenged lefties, and over the course of the season the home run count at the Coliseum declined to the same level as other National League parks. At the end of the season, The Sporting News noted, there had been only 21 more home runs in the Coliseum than there were in the smaller Ebbets Field, where the Dodgers had played in Brooklyn.[18] During the off-season, Frick announced a rule change stipulating that any new stadium built for major-league play must have all its fences at least 325 feet (99 m) from home plate. This was widely viewed as a response to the preseason controversy.[23]

The only hitter to truly benefit from the short left-field fence was Wally Moon, a left-handed outfielder who began playing for the Dodgers the next season. He figured out how to lift balls high enough so that they dropped down, almost vertically, just beyond the screen. This brought him 37 of his 49 homers for that season. He was not accused of exploiting the short distance to the fence for Chinese home runs. Instead, he was celebrated for his inventiveness; similar home runs have since been called "Moon shots" in his honor.[18]

Game 5 of that year's World Series, ultimately won by the Dodgers over the Chicago White Sox, would be the last postseason Major League Baseball game played at the Coliseum. After two more seasons at the Coliseum, the Dodgers moved to Dodger Stadium in 1962, where they have played home games ever since. After the then-Los Angeles Angels' first American League season in 1961, the club asked for a new home in the Los Angeles area, initially asking if they could play in the Coliseum. Frick refused to let them.[24]

In 2008, to celebrate their 50th anniversary in Los Angeles, the Dodgers played a preseason exhibition game at the Coliseum against the Boston Red Sox, losing by a score of 7-1. The wire mesh screen was restored, this time at the 60-foot (18 m) height Frick had sought because an additional section of seats had been added there since 1959, shortening left field to 201 feet (61 m). A Dodgers executive noted that it mimicked the Green Monster in left field at Fenway Park, the Red Sox' home field.[18]

1962-63: Return of the Polo Grounds

In 1962, baseball returned to the Polo Grounds when the National League created the New York Mets as an expansion team, to replace the Giants and Dodgers. The new team used the old stadium for two seasons while Shea Stadium was built out in the Queens neighborhood of Flushing. The Mets lost the franchise's first six games at the Giants' former home, on their way to a 40–120 record, still the most losses in a major-league season, but in those games they and their opponents hit ten home runs apiece. Sportswriters took notice, and one AP writer picked up where Dick Young had left off eight years before: "So solly, honorable sir. Chinese home run not buried in Coliseum. Making big comeback in honorable ancient Polo Grounds".[25]

While the team's poor play and last-place finishes in its two seasons in the Polo Grounds left few individual home runs over the right-field fence to become the subject of popular comment and mockery as Rhodes' had, the term was still in use during the team's radio broadcasts, as Dana Brand recalled in 2007:

If you hit a 300-foot home run in the Polo Grounds, Lindsey Nelson or Ralph Kiner or Bob Murphy would call it a Chinese home run. Obviously, they wouldn't call it a Chinese home run now, even if you could still hit a 300-foot home run. To this day, I don't know what made a home run like this Chinese. Was it because it was short, something a small person could hit? Was there some implication that it was tricky or cheap or sneaky? What a strange world that was.[26]

Problems in completing Shea Stadium forced the Mets to stay one season more. At one point during the season, manager Casey Stengel alluded to the short home runs when berating pitcher Tracy Stallard. "At the end of this season they're gonna tear this place down", he reminded Stallard as he took him out of a game in which he had given up several home runs. "The way you're pitching, that right field section is gone already". In April 1964, the Polo Grounds were finally demolished and eventually replaced with a public housing project.[27]

1965–present: Disuse

Use of the term largely faded out afterwards, and it was largely seen as offensive. In 1981 San Francisco Chronicle columnist Herb Caen criticized Oakland A's radio announcer Bill King for saying a Bobby Murcer shot was "not a Chinese home run". Caen called the remark "racist" and wrote: "I'm sure he has heard from militant Oriental groups, all of which hit hard".[2]

Secondary definition

Dickson found another usage, referring to a high foul ball that travels a great distance, usually behind home plate. In Stephen King's 1980 short story "The Monkey", anthologized five years later in Skeleton Crew, the protagonists' father recalls days watching sandlot games during his own childhood, when he "was too small to play, but he sat far out in foul territory sucking his blueberry Popsicle and chasing what the big kids called 'Chinese home runs'". Dickson wrote to King, who told him two years later that he had first heard the term when learning to play baseball in his own childhood, during a time when he lived, briefly, in Stratford, Connecticut. After he returned to his native Maine in 1958, the same year the Giants and Dodgers moved west, he recalled hearing it again. "In both cases", he told Dickson, "a Chinese home run was a foul ball, usually over the backstop". Dickson concluded from his correspondence that that use may well be limited to New England.[2] All three definitions submitted to the online Urban Dictionary in the early 21st century are in accord with this usage.[28]

According to Dickson, one of the etymologies submitted to Joe Falls' Sporting News column, by a St. Louis man named Tom Becket, may explain this usage. "In this version, the term harks back to the turn of the 20th century and a game played in Salem, Massachusetts, between teams of Irish and Polish immigrants". The game was close, and went deep into extra innings. By the 17th inning, only one ball was left. A shortstop named Chaney, playing for the Irish team, fouled the ball deep into unmowed grass and weeds behind the backstop. After searching through it for 20 minutes, the umpire gave up and declared that the Polish team had forfeited the game since it had failed to provide enough balls. "So the cheer went up, 'Chaney's home run won the game!'", Becket explained. "Various misunderstandings as to dialects eventually brought it around to the now-familiar 'Chinese home run'".[2]

See also

- Chinese fire drill, another derogatory term from the early 20th century that survived that era

- Glossary of baseball

- Left-arm unorthodox spin, a cricket bowling technique sometimes referred to as a Chinaman, supposedly after an early player to use it

Notes

- ↑ The cover design, with its suggestions of the Yellow Peril, may also have reflected another change in American perceptions of the Chinese. Nine years earlier, the Communists had won China's civil war and established the People's Republic of China, ostensibly allied with the Soviet Union against the U.S. in the Cold War. At that time, with China undergoing its Great Leap Forward, an attempt to rapidly industrialize the country, Americans were particularly fearful of what Chinese workers might be able to accomplish.

References

- ↑ "Origins: A simple word game for use in human relations trainings" (PDF). Teaching Tolerance. p. 6. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Dickson, Paul (2011). Skip McAfee, ed. The Dickson Baseball Dictionary (3d ed.). New York: W.W. Norton & Co. pp. 182–84. ISBN 9780393073492. Retrieved March 10, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Madden, Bill (2014). 1954: The Year Willie Mays and the First Generation of Black Superstars Changed Major League Baseball Forever. Da Capo Press. p. 242. ISBN 9780306823329. Retrieved March 12, 2015.

- ↑ Neyer, Rob (May 8, 2013). "Seven things you can't say on (baseball) television". SB Nation. Retrieved March 10, 2015.

- ↑ O'Toole, Grant (November 4, 2010). "And in (additional) honor of the Giants' World Series win...". ADS-L (Mailing list). Retrieved March 12, 2015.

- 1 2 Lighter, Jonathan (November 3, 2010). "And in (additional) honor of the Giants' World Series win...". ADS-L (Mailing list). Retrieved March 12, 2015.

- 1 2 Schlossberg, Dan (2008). Baseball Bits. Penguin Books. p. 185. ISBN 9781440630002. Retrieved March 12, 2015.

- ↑ Dickson, 466.

- 1 2 3 Hardy Jr., James D. (2007). Baseball and the Mythic Moment: How We Remember the National Game. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. pp. 32–34. ISBN 9780786426508. Retrieved March 13, 2015.

- ↑ Maney, Richard (September 10, 1950). "Shades of Abner Doubleday!; From a grandstand seat on Broadway, this baseball fan rises to denounce the modern game as ersatz, a fraud and a bore.". The New York Times. Retrieved March 13, 2015.

Another victim of the Chinese home run is the stolen base.

- ↑ Webster, Gary (2013). 0.721: A History of the 1954 Cleveland Indians. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. p. 158. ISBN 9781476605623. Retrieved March 16, 2015.

- ↑ Billheimer, John (2007). Baseball and the Blame Game: Scapegoating in the Major Leagues. McFarland. pp. 94–96. ISBN 9780786429066. Retrieved March 14, 2015.

- ↑ Knight, Jonathan (2013). Summer of Shadows: A Murder, A Pennant Race, and the Twilight of the Best Location in the Nation. Clerisy Press. p. 110. ISBN 9781578604678. Retrieved March 14, 2015.

- ↑ Daley, Arthur (September 30, 1954). "Sports of the Times: The Psychic Durocher Clicks". The New York Times. Retrieved March 14, 2015.

- ↑ "Lot #641: 1954 "Chinese Home Run" Protest Letter "The Sporting News Collection Archives" Original 8" x 10" Photo (Sporting News Collection Hologram/MEARS Photo LOA) – Lot of 2". Mears Online Auctions. April 30, 2011. Retrieved March 19, 2015.

- ↑ Talese, Gay (March 3, 1958). "Rigney's Players Yearn for Cabbies, Cheap Homers and Even Ebbets Field". The New York Times. Retrieved March 14, 2015.

- 1 2 3 Morales, Bill (2011). Farewell to the Last Golden Era: The Yankees, the Pirates and the 1960 Baseball Season. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. pp. 81–82. ISBN 9780786485680. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Schwarz, Alan (March 26, 2008). "201 Feet to Left, 440 Feet to Right: Dodgers Play the Coliseum". The New York Times. Retrieved March 14, 2015.

- ↑ White, Gaylon H. (2014). The Bilko Athletic Club: The Story of the 1956 Los Angeles Angels. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 31. ISBN 9780810892903. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- 1 2 McCue, Andy (2014). Mover and Shaker: Walter O'Malley, the Dodgers, and Baseball's Westward Expansion. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. pp. 221–22. ISBN 9780803255050. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- 1 2 Szalontai, James D. (2002). Close Shave: The Life and Times of Baseball's Sal Maglie. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. p. 356. ISBN 9780786411894. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- ↑ Elias, Robert (2010). The Empire Strikes Out: How Baseball Sold U.S. Foreign Policy and Promoted the American Way Abroad. The New Press. p. 1961. ISBN 9781595585288. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- ↑ Vincent, David (2011). Home Run: The Definitive History of Baseball's Ultimate Weapon. Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books. p. 104. ISBN 9781597976572. Retrieved March 18, 2015.

- ↑ Purdy, Dennis (2006). The Team by Team Encyclopedia of Major League Baseball. Workman Publishing. p. 510. ISBN 9780761139430. Retrieved March 18, 2015.

- ↑ "Chinese Home Run Making Big Comeback at Polo Grounds". Lawrence Journal-World. Lawrence, Massachusetts. Associated Press. April 21, 1962. Retrieved March 16, 2015.

- ↑ Brand, Dana (2007). Mets Fan. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. p. 18. ISBN 9780786482481. Retrieved March 16, 2015.

- ↑ Leuchtenberg, William E. (2002). American Places: Encounters with History. Oxford University Press. p. 308. ISBN 9780195152456. Retrieved March 16, 2015.

- ↑ "Chinese home run". Urban Dictionary. 2006–2011. Retrieved March 17, 2015.