Ohio Replacement Submarine

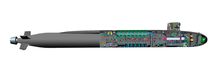

Graphic artist concept (2012) | |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Preceded by: | Ohio-class submarine |

| Planned: | 12 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type: | Ballistic missile submarine (SSBN) |

| Displacement: | 20,810 long tons (submerged)[1] |

| Length: | 561 feet (171 m)[1] |

| Beam: | 43 feet (13 m)[1] |

| Propulsion: | Nuclear reactor, turbo-electric drive, pump-jet[1] |

| Range: | Unlimited |

| Complement: | 155 (accommodation)[1] |

| Sensors and processing systems: | Enlarged version of Virginia LAB sonar[1] |

| Armament: | 16 × Trident D5[2] |

The Columbia-class submarine, also known as the Ohio Replacement Submarine (formerly the SSBN-X Future Follow-on Submarine) is a future United States Navy nuclear submarine designed to replace the Trident missile-armed Ohio-class ballistic missile submarines.[3] The first submarine is scheduled to begin construction in 2021 and enter service in 2031 (some 50 years after its immediate predecessor, the Ohio class, entered service).[4][5] From there, the submarine class will serve through 2085.[6]

Overview

The Columbia-class submarine is being designed to replace the Ohio-class ballistic missile submarines. The Ohio-class of submarines are aging and the first boat in that class is scheduled to be decommissioned in 2027 with the remaining scheduled to be decommissioned yearly following the first boat’s decommissioning. The Ohio replacement’s role in the fleet will be to replace the decommissioned Ohio submarines and maintain the submarine presence in the United States’ strategic nuclear force.[2]

Electric Boat is designing the Ohio replacement submarines with assistance from Newport News Shipbuilding. A total of 12 boats are planned to be built, with construction of the first boat planned to begin in 2021. Each submarine will have 16 missile tubes and each tube will be capable of carrying a Trident II D5LE missile. The submarines will be 560 feet long and 43 feet in diameter. That is the same length as the Ohio-class submarine design, and one foot larger in diameter.[2]

Sources such as the Federation of American Scientists (FAS) suggest that the number of boats should be lower due to an ever decreasing number of deterrent patrols in the post-Cold War era and as a cost reduction measure. The FAS analyzed current and past Ohio-class boat deployments to calculate the number of yearly SSBN deterrent patrols. The results of that study found that yearly deterrent patrols reduced by 56% from 1999 to 2013. The FAS argues that fewer boats could be built if those boats were to maintain the higher deterrent patrol rate of years past.[7] However, the United States Navy disagrees with the FAS assessment.

In order to determine the number of submarines required to support the United States’ strategic nuclear force, the United States Navy conducted a number of studies. Those studies looked at the number of missiles required to be at sea and on station at any given time, the number of missiles each boat should be armed with, the likelihood that a boat will remain undiscovered by the enemy and be capable of launching its missiles, and how the maintenance schedule of each boat will impact that boat’s availability to be deployed on mission.[8] A number of cost-reduction studies were also conducted that explored multiple design and construction possibilities. The cost-reduction studies explored the possibility of adding missile tubes to the design of the Virginia-class of fast-attack submarine, the possibility of building Ohio- class replacement submarines using updated Ohio-class designs, as well as developing an entirely new Ohio replacement boat design.[9]

Using the information from these studies, the United States Navy concluded that a new submarine design would be the least expensive option that would be capable of meeting all of the technical requirements.[8] Maintenance schedules and maintenance costs, including what would have been a required mid-life refueling, detracted from both the modified Virginia-class, and updated Ohio-class design options.[2] The new boat design is planned to incorporate technology and components from both the Ohio and Virginia submarine classes where possible as a cost saving measure. Also, the nuclear core of the new design is planned to be a life-of-ship core, meaning that there will be no mid-life refueling required as is required with the Ohio class submarines.[10][11]

It is estimated that in fiscal year 2010 dollars, the first boat of the new class will cost $6.2 billion in construction costs with an additional 4.2 billion in non-recurring design and engineering costs.[2] The Navy has a goal of reducing the average cost of ships 2 through 12 in the class to $4.9 billion each (year 2010 dollars).[10] including the exploration of several options that included using a variant of the Virginia-class nuclear attack submarines fitted with a missile housing, a dedicated SSBN, either with a new hull or based on an overhaul of the current Ohio.[12][13] The total lifecycle cost of the entire class is estimated at $347 billion.[10] The high cost of the submarines is expected to cut deeply into Navy shipbuilding.[14]

In April 2014, the Navy completed ship specification documents for the Ohio Replacement Program submarines. The technical details consist of three 100-page volumes of documents detailing its configuration, design, and technical requirements. There are 159 ship specifications including weapons systems, escape routes, fluid systems, hatches, doors, sea water systems, and a set ship length of 560 feet, partly to allow for more volume inside the pressure hull.[6]

In March 2016 the U.S. Navy announced that General Dynamics Electric Boat was chosen as the prime contractor and lead design yard.[15] Electric Boat will carry out the majority of the work, on all 12 submarines, including final assembly[16] (Note: all 18 Ohio class submarines were built at Electric Boat as well).[17] Huntington Ingalls Industries’ Newport News Shipbuilding will serve as the main subcontractor, participating in the design and construction and performing 22 to 23 percent of the required work.[18]

On July 28, 2016 it was reported the first ship of the class will be named USS Columbia to commemorate the U.S. capital.[19] Presumably the class will become known as the Columbia-class.

General characteristics

Although still evolving, the following are some of the ship characteristics for the SSBN(X) design:[4][20]

- Expected 42-year service life (it is planned that each submarine will carry out 124 deterrent patrols during its service life)[21]

- Life-of-the-ship nuclear fuel core that is sufficient to power the ship for its entire expected service life, unlike the Ohio-class submarines that require a mid-life nuclear refueling[11]

- Missile launch tubes that are the same size as those of the Ohio class, with a diameter of 87 inches (2,200 mm) and a length sufficient to accommodate a D-5 Trident II missile

- Ship beam at least as great as the 42-foot (13 m) beam of the Ohio-class submarines

- 16 missile launch tubes[2] instead of 24 missile launch tubes on Ohio-class submarines. A recent report (as of November 2012) suggested that the boats will have 12 Submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM) silos/tubes.[22] However, other sources do not support this.[23][24]

- Although the SSBN(X) is to have fewer launch tubes than the Ohio-class submarine, SSBN(X) is expected to have a submerged displacement about the same as that of Ohio-class submarines

Also, the US Navy has stated that "owing to the unique demands of strategic relevance, [SSBN(X)s] must be fitted with the most up-to-date capabilities and stealth to ensure they are survivable throughout their full 40-year life span."[25]

In November 2012, the U.S. Naval Institute revealed, citing Naval Sea Systems Command, additional design information:[24]

- X-shaped stern control surfaces (hydroplanes)

- Sail-mounted dive planes

- Electric drive

- Off-the-shelf equipment developed for previous submarine designs (Virginia-class SSNs), including a pump-jet propulsor, anechoic coating and a Large Aperture Bow (LAB) sonar system.

The boats may also be equipped with a Submarine Warfare Federated Tactical System (SWFTS), a cluster of systems that integrate sonar, optical imaging, weapons control etc.[26][27][28]

Electric drive

Electric drive is a propulsion system that uses an electric motor which turns the propeller of a ship/submarine. It is part of a wider (Integrated electric power) concept whose aim is to create an "all electric ship".[29][30] Electric drive should reduce the life cycle cost of submarines while at the same time improving acoustic performance.[31][32]

Turbo-electric drive had been used on US capital ships (battleships and aircraft carriers) in the first half of the twentieth century.[33] Later on, two nuclear-powered submarines USS Tullibee (SSN-597) and USS Glenard P. Lipscomb (SSN-685) were equipped with turboelectric drive but experienced reliability issues during their service life and deemed underpowered and maintenance heavy.[34][35][36] Currently (as of 2013), only the French Navy uses turboelectric drive on its nuclear-powered Triomphant class submarines.[37]

Conceptually, electric drive is only a segment of the propulsion system (it does not replace the nuclear reactor or the steam turbines). Instead it replaces reduction gearing (mechanical drive) used on earlier nuclear-powered submarines.[29] In 1998, the Defence Science Board envisaged a nuclear-powered submarine which would utilise an advanced electric drive eliminating the need for both reduction gearing (mechanical drive) as well as steam turbines, however.[38]

In 2014, Northrop Grumman was chosen as the prime designer and manufacturer of the turbine generator units.[39] Turbine generators convert mechanical energy from the steam turbines into electrical energy.[40] The electrical energy is then used for powering onboard systems as well as for propulsion via electric motor.[39][41]

Various electric motors are being or have been developed for both military and non-military vessels.[42] Those being considered for application on future U.S. Navy submarines include: permanent magnet motors (being developed by General Dynamics and Newport News Shipbuilding) and a high-temperature superconducting (HTS) synchronous motors (being developed by American Superconductors as well as General Atomics).[42][43][44]

More recent data shows that the US Navy appears to be focusing on permanent-magnet, radial-gap electric propulsion motors (e.g. Zumwalt-class destroyers use an advanced induction motor).[45] Permanent magnet motors are being tested on the Large Scale Vehicle II for possible application on late production Virginia class SSNs as well as future submarines.[46][47] Permanent magnet motors (developed by Siemens AG) are used on Type 212 class submarines.[48]

Reports on the Royal Navy Dreadnought-class submarine (i.e., the class that will replace the Vanguard class SSBNs) state that the submarines may have submarine shaftless drive (SSD) with an electric motor mounted outside the pressure hull.[49] SSD was evaluated by the U.S. Navy as well but it remains unknown whether the Ohio class replacement will feature it.[50][51] On contemporary nuclear submarines steam turbines are linked to reduction gears and a shaft rotating the propeller/pump-jet propulsor. With SSD, steam would drive electric turbogenerators (i.e., generators powered by steam turbines) which would be connected to a non-penetrating electric junction at the aft end of the pressure hull, with a watertight electric motor mounted externally (perhaps in an Integrated Motor Propulsor arrangement),[52] powering the pump-jet propulsor,[49] although SSD concepts without pump-jet propulsors also exist.[53] More recent data, including a Ohio Replacement scale model displayed at the Navy League’s 2015 Sea-Air-Space Exposition, indicates that the Ohio Replacement will feature a pump-jet propulsor visually similar to the one used on Virginia class SSNs.[54][24] The class will share components from the Virginia class in order to reduce risk and cost of construction.[54][55]

Common missile compartment

In December 2008, General Dynamics Electric Boat Corporation was selected to design the Common Missile Compartment which will be used on the Ohio-class successor.[22]

In 2012, the US Navy's announced plans for its SSBN(X) to share a common missile compartment (CMC) design with the Royal Navy's proposed replacement for its own Vanguard-class ballistic missile submarine.[56] The CMC will house SLBMs in so-called quad packs.[57][58]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Ohio Replacement Program". United States Naval Institute. 18 October 2012. Retrieved 2012-11-01.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 O'Rourke, Ronald. "Navy Ohio Replacement (SSBN[X]) Ballistic Missile Submarine Program: Background and Issues for Congress". https://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/weapons/R41129.pdf

- ↑ "SSBN-X Future Follow-on Submarine". GlobalSecurity.org. 24 July 2011. Retrieved 2011-07-24.

- 1 2 "SENEDIA Defense Innovation Days" (PDF). Senedia.org. 5 September 2014. Retrieved 2016-08-20.

- ↑ This story was written by Lt. Rebecca Rebarich, Commander Submarine Group Ten Public Affairs. "1,000 Trident Patrols: SSBNs the Cornerstone of Strategic Deterrence". Navy.mil. Retrieved 2016-08-20.

- 1 2 Kris Osborn. "Navy Finishes Specs for Future Nuclear Sub". Dodbuzz.com. Retrieved 2016-08-20.

- ↑ Kristensen, Hans M. (30 April 2013). "Declining Deterrent Patrols Indicate Too Many SSBNs". FAS Strategic Security Blog. Federation of American Scientists. Retrieved 2013-08-17.

- 1 2 Kristensen, Hans M. (24 July 2013). "SSBNX Under Pressure: Submarine Chief Says Navy Can't Reduce". FAS Strategic Security Blog. Federation of American Scientists. Retrieved 2013-08-17.

- ↑ Kelly, Jason. "Facts We Can Agree Upon About Design of Ohio Replacement SSBN". Navylive.dodlive.mil. Retrieved 2013-08-17.

- 1 2 3 "U.S. Nuclear Modernization Programs". Arms Control Association. Retrieved 2012-11-01.

- 1 2 "Ohio-class Replacement Will Carry "Re-packaged and Re-hosted" Weapons System". Defense Media Network. 2011-02-04. Retrieved 2013-02-06.

- ↑ O'Rourke 2012, p. 29.

- ↑ Kelly, Jason. "Facts We Can Agree Upon About Design of Ohio Replacement SSBN". Navylive.dodlive.mil. Retrieved 2013-08-17.

- ↑ Ratnam, Gopal; Capaccio, Tony (9 March 2011). "U.S. Navy Sees 20-Year, $333 Billion Plan Missing Ship Goals". Bloomberg. Retrieved 2011-03-09.

- ↑ Grace Jean (2016-03-30). "USN taps General Dynamics Electric Boat as prime contractor for Ohio Replacement Programme | IHS Jane's 360". Janes.com. Retrieved 2016-08-20.

- ↑ "Ohio Replacement Plan Is Good News For Electric Boat « Breaking Defense - Defense industry news, analysis and commentary". Breakingdefense.com. 2016-03-29. Retrieved 2016-08-20.

- ↑ "SSBN / SSGN Ohio Class Submarine". Naval Technology. 2011-06-15. Retrieved 2016-08-20.

- ↑ "Newport News Shipbuilding's share of Virginia-class submarine deliveries to grow | Defense & Shipyards". Pilotonline.com. 2016-03-29. Retrieved 2016-08-20.

- ↑ Sam LaGrone (2016-07-28). "New U.S. Navy Nuclear Sub Class to Be Named for D.C". News.usni.org. Retrieved 2016-08-20.

- ↑

- ↑ "Ohio Replacement Submarine Starts Early Construction".

- 1 2 "CMC Program to Define Future SSBN Launchers for UK, USA". Defense Industry Daily. 25 November 2012. Retrieved 2012-12-03.

- ↑ "An Analysis of the Navy's Fiscal Year 2013 Shipbuilding Plan" (PDF). Congressional Budget Office. Retrieved 2012-12-03.

- 1 2 3 "Ohio-class Replacement Details". US Naval Institute. 1 November 2012. Retrieved 2012-12-03.

- ↑ O'Rourke 2012, pp. 10–11.

- ↑ "On Watch 2011". Navsea.navy.mil. Retrieved 2013-02-06.

- ↑ Keller, John (2012-04-15). "Lockheed Martin to adapt submarine combat systems for network-centric warfare operations at sea - Military & Aerospace Electronics". Militaryaerospace.com. Retrieved 2014-02-02.

- ↑

- 1 2 "An Integrated Electric Power System: the Next Step". Navy.mil. Retrieved 2013-02-06.

- ↑ "Going Electric". Defense Media Network. 2010-06-14. Retrieved 2013-02-06.

- ↑ "Propulsion Systems for Navy Ships and Submarines" (PDF). Government Accounting Office. 6 July 2006.

- ↑ "Technology for the United States Navy and Marine Corps, 2000-2035 Becoming a 21st-Century Force: Volume 2: Technology". Nap.edu. 2003-06-01. Retrieved 2013-05-30.

- ↑ Tony DiGiulian. "Turboelectric Drive in American Capital Ships". Navweaps.com. Retrieved 2013-02-06.

- ↑ Paul Lambert. "USS Tullibee – History". USS Tullibee SSN 597. Retrieved 2013-02-06.

- ↑ "Submarine Technology thru the Years". Navy.mil. 1997-07-19. Retrieved 2013-02-06.

- ↑ Sam LaGrone (2013-03-28). "Secret Nuclear Redesign Will Keep U.S. Subs Running Silently for 50 Years | Danger Room". Wired.com. Retrieved 2013-05-30.

- ↑ "SSBN Triomphant Class". Naval Technology. 2011-06-15. Retrieved 2013-02-06.

- ↑ "Submarine of the Future". Fas.org. Retrieved 2013-02-06.

- 1 2 "News". Northrop Grumman.

- ↑ "Electricity 101 - GE Power Generation".

- ↑ Kris Osborn. "Ohio Replacement Subs To Shift To Electric Drive |". Defensetech.org. Retrieved 2016-08-20.

- 1 2 Bogomolov, M.D. (22 January 2013). "Concept study of 20 MW highspeed permanent magnet synchronous motor for marine propulsion" (PDF). Eindhoven University of Technology.

- ↑ O'Rourke, Ronald (11 December 2006). "Navy Ship Propulsion Technologies: Options for Reducing Oil Use — Background for Congress" (PDF). Federation of American Scientists. RL33360.

- ↑ Sonal Patel (2009-03-01). "Superconductor Motor for Navy Passes Full-Power Test :: POWER Magazine". Powermag.com. Retrieved 2013-05-30.

- ↑ "DDG-1000 Zumwalt Class Destroyer". Defense.about.com. 2012-11-01. Retrieved 2013-02-06.

- ↑ "Small Subs Provide Big Payoffs for Submarine Stealth". Navy.mil. Retrieved 2013-02-06.

- ↑ Dan Petty. "The US Navy - Fact File: Large Scale Vehicle - LSV 2". Navy.mil. Retrieved 2013-02-06.

- ↑ "SINAVYCIS Permasyn" (PDF). Siemens AG. 2009.

- 1 2 "SSBN "Strategic Successor Submarine" project". Harpoon Headquarters. Retrieved 2013-08-17.

- ↑ "Tango Bravo: breaking down barriers in submarine design". Janes.com. 2007-03-23. Retrieved 2013-05-30.

- ↑ "Tango Bravo R&D Project to Drive Down Sub Size". Defenseindustrydaily.com. Retrieved 2013-05-30.

- ↑ "Torpedoes and the Next Generation of Undersea Weapons". Navy.mil. Archived from the original on April 20, 2015. Retrieved 2013-06-01.

- ↑ Kuhn, Dave; Torrez, Joe; Fallier, William (2006). "The Rim Electric Drive - Internal Submarine" (PDF). Naval Construction and Engineering. Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- ↑ Ronald O'Rourke. "Navy Ohio Replacement (SSBN[X]) Ballistic Missile Submarine Program: Background and Issues for Congress" (PDF). Fas.org. Retrieved 2016-08-20.

- ↑ O'Rourke 2012, pp. 12–13.

- ↑ "Navy Signs Specification Document for the Ohio Replacement Submarine Program, Sets forth Critical Design Elements". Navy News Service. 6 September 2012. NNS120906-13. Retrieved 2013-04-21.

- ↑ Patani, Arif (2012-09-24). "Next Generation Ohio-Class". Navylive.dodlive.mil. Retrieved 2013-04-21.

Bibliography

- Breckenridge, Richard (22 June 2013). "Facts We Can Agree Upon About Design of Ohio Replacement SSBN". NavyLive. Retrieved 2013-06-27.

- O'Rourke, Ronald (18 October 2012). "Navy Navy SSBN(X) Ballistic Missile Submarine Program: Background and Issues for Congress" (PDF). R41129. Congressional Research Service. Retrieved 2011-06-24.

- Thompson, Loren (20 June 2011). "The Submarine That Might Save America". Forbes. Retrieved 2011-06-23.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Columbia class submarines. |