Connecticut in the American Civil War

|

|

Union states in the American Civil War |

|---|

|

|

| Border states |

| Dual governments |

| Territories and D.C. |

The New England state of Connecticut played a relatively small, but important role in the American Civil War, providing arms, equipment, money, supplies, and manpower for the Union Army, as well as the Union Navy. Several Connecticut politicians played significant roles in the Federal government and helped shape its policies during the war and the subsequent Reconstruction.

Connecticut at the beginning of the war

Before the Civil War, Connecticut residents such as Leonard Bacon, Simeon Baldwin, Horace Bushnell, Prudence Crandall, Jonathan Edwards (the younger) and Harriet Beecher Stowe, were active in the abolitionist movement,[1] and towns such as Farmington[2] and Middletown were stops along the Underground Railroad.[3] Slavery in Connecticut had been gradually phased out beginning in 1797 with less than 100 slaves in Connecticut by 1820; slavery was not completely outlawed, however, until 1848.[4]

The state, along with the rest of New England, had voted for Republican presidential candidate John C. Frémont in the 1856 presidential election, giving "the Pathfinder" all 6 electoral votes. The Republicans opposed the extension of slavery into the territories, and Connecticut residents embraced their slogan "Free speech, free press, free soil, free men, Frémont and victory!"[5] Four years later, once again Connecticut favored the Republican candidate, this time Illinois lawyer Abraham Lincoln. Residents cast 58.1% of their ballots for Lincoln, versus 20.6% for Northern Democrat Stephen Douglas and 19.2% for Southern Democrat John C. Breckinridge. A handful of voters (1,528 or 2% of the ballots cast) favored John Bell of Tennessee.[6]

The 1860 U.S. Census enumerated 460,147 people living in Connecticut as of June 1 of that year. Of that count, 451,504 were white, with only 8,627 blacks and 16 Indians. More than 80,000 of the whites were foreign-born, with 55,000 coming from Ireland. More than 20% of the population was still engaged in farming, but industry and the trades had become major employers.[7] Starting in the 1830s, and accelerating when Connecticut abolished slavery entirely in 1848, African Americans from in- and out-of-state began relocating to urban centers for employment and opportunity, forming new neighborhoods such as Bridgeport's Little Liberia.[8]

War efforts

Governor William Buckingham was a wealthy businessman and energetic Republican; he won a narrow election in April 1860, as a moderate Republican who was temperamentally cautious. His anti-slavery attitude hardened as the war went on. Even before Fort Sumter, he collaborated with fellow Republican governors in New England, and alerted the state militia to watch out for sabotage. The state specialized in machinery, and had a strong reputation for making artillery and firearms. The opposition party, the Democrats, were largely dominated by the antiwar or peace element, led by former governor Thomas H. Seymour. When Lincoln called for troops the day after Fort Sumter, Buckingham mobilized militia units, but had no state authority for financing the war. The legislature was not in session, but the banks eagerly volunteered to loan money to the state until the Legislature made good.[9]

Military recruitment and participation

Following the bombardment of Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor in April 1861, a few days later, on the 15th, President Lincoln called for volunteers to join the new Union army. The next day, Governor William A. Buckingham, like Lincoln a Republican, issued a proclamation urging his citizens to join state-sponsored regiments and artillery batteries.[10] In response, by the end of the month, the 1st Connecticut Infantry and two other regiments had been raised and recruited for a term of three months (all the time that was expected to be needed to crush the rebellion and end the war). Daniel Tyler of Brooklyn was selected as the 1st Regiment's initial colonel, and the regiment arrived in Washington, D.C. on May 10.[11]

The state furnished thirty full regiments of infantry, including two that were made up of black men. Two regiments of heavy artillery also served as infantry toward the end of the war. Connecticut also supplied three batteries of light artillery and one regiment of cavalry.[12][13]

Fort Trumbull in New London served as an organizational center for Union troops and headquarters for the U.S. 14th Infantry Regiment. Here, troops were recruited and trained before being sent to war.[14] Among the regiments trained there was the 14th Connecticut Infantry, which played a prominent role in the Army of the Potomac's defense of Cemetery Ridge during the Battle of Gettysburg.[15] The 2nd Connecticut Heavy Artillery (19th Connecticut Infantry) suffered significant casualties in the 1864 Overland Campaign and the Siege of Petersburg. Among the troops from the "Nutmeg State" that fought in the Trans-Mississippi Theater was the 9th Connecticut Infantry, which aided in the capture of New Orleans, Louisiana, as part of the "New England Brigade."

During the war, the State Hospital in New Haven (a precursor to Yale-New Haven Hospital) was leased to the government to serve as the Knight U.S. Army General Hospital. 23,340 soldiers were treated in the hospital with only 185 deaths.[16]

One of the first officers killed in the Civil War was New Haven's Theodore Winthrop, who died in an early engagement at Big Bethel in western Virginia.[17]

Casualties from Connecticut military units during the war included 97 officers and 1094 enlisted men killed in action, with another 700 men dying from wounds while more than 3,000 perished from disease. Twenty-seven men were executed for crimes, including desertion. More than 400 men were reported as missing; the majority were likely held by the Confederate Army as prisoners of war.[18]

The homefront

Prominent among military manufacturers with Connecticut ties was the New Haven Arms Company, which provided the army with the Henry rifle, developed by New Haven's Benjamin Tyler Henry.[19] Colt's Manufacturing Company, founded and owned by Hartford-born industrialist Samuel Colt, was another significant arms and munitions supplier. The company shipped large quantities of sidearms to the Union Navy.[20] The Hartford-based firm of Pratt & Whitney provided machinery and support equipment to Army contractors to produce weapons. Most of the brass buttons used on Federal uniforms, belt buckles and other fittings, were made in Waterbury, the "Brass City", notably by the Chase Brass and Copper Company.[21] The shipyards at Mystic provided ships for the Union Navy. The USS Monticello (1859), USS Galena (1862), USS Varuna (1861) were all built at Mystic.

The popular late war marching song Marching Through Georgia was written by Henry Clay Work, a Middletown resident.[22]

Notable leaders from Connecticut

Glastonbury native Gideon Welles was a prominent member of the Lincoln Cabinet and perhaps its leading conservative. He was the Secretary of the Navy from 1861 to 1869 and was the architect of the planning and execution of the blockade of Southern ports. During his tenure, he increased the size of the United States Navy tenfold.[23]

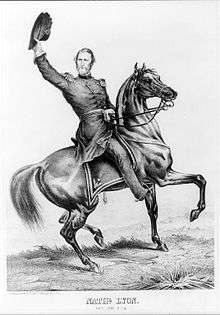

Shortly after the war began, Col. Daniel Tyler of the 1st Connecticut was promoted to brigadier general. Later, other field officers in Connecticut regiments such as Alfred Terry, Henry Warner Birge (both born in Hartford), and Robert O. Tyler of the 4th Connecticut Infantry would be raised in rank to general. Some Connecticut-born men with antebellum U.S. Army service also became leading generals early in the war, including Ashford-born Nathaniel Lyon, one of the war's earliest army commanders to be killed when he was shot down at the Battle of Wilson's Creek in Missouri. Cornwall's John Sedgwick commanded the Union VI Corps for much of the war until killed at the Spotsylvania Court House. He was succeeded by Horatio G. Wright of Clinton, a long-time officer in the Regular Army.[24]

Major General Joseph K. Mansfield of Middletown led the II Corps of the Union Army of the Potomac during the middle of 1862. He was killed in action at the Battle of Antietam during the 1862 Maryland Campaign.[25] Another casualty of the fighting at Antietam was Brig. Gen. George Taylor, who had been educated at a private military academy in Middletown.

Joseph R. Hawley of New Haven commanded a division in the Army of the Potomac during the Siege of Petersburg and was promoted in September 1864 to brigadier general. Concerned over keeping the peace during the November elections, Hawley commanded a hand-picked brigade shipped to New York City to safeguard the election process.[26] Other Union generals with Connecticut roots included Henry W. Benham of Meriden, Luther P. Bradley of New Haven, William T. Clark of Norwich, Orris S. Ferry of Bethel, and Alpheus S. Williams of Deep River.[24]

New Haven native Andrew Hull Foote received the Thanks of Congress for his distinguished actions in commanding the Mississippi River Squadron gunboat flotilla in the capture of Forts Henry and Donelson and Island No. 10.[27]

Civil War attractions in Connecticut

The New England Civil War Museum is housed in the Memorial Building in Rockville. It includes the old headquarters of the local post of the Grand Army of the Republic. The museum includes the Hirst Brothers' Collection (14th Connecticut Volunteer Infantry), the Thomas F. Burpee Collection (colonel, 21st Connecticut Volunteer Infantry), and the Weston Collection (musician, 5th Connecticut Volunteer Infantry). The museum and library (along with the hall and its rooms) are the property of the Alden Skinner Camp #45 of the Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War. In addition, the museum contains the O'Connell-Chapman Library, which has more than a thousand volumes of Civil War literature.[28]

Fort Trumbull now serves as a state park with exhibits detailing its history.[29]

Memorialization

There are well over 100 Civil War Monuments in Connecticut.[30] In New Haven alone there are eight.[31] The Soldiers and Sailors Monument is located on the 366-foot summit of East Rock in New Haven. The monument is visible for miles from the surrounding area. It honors the residents of New Haven who gave their lives in the American Revolutionary War, the War of 1812, the Mexican-American War, and the American Civil War.[32] Other monuments in New Haven include the Broadway Civil War Memorial (1905) and the Yale Civil War Memorial at Woolsey Hall (1915).[31] The memorial in Woolsey Hall is notable for honoring both Union and Confederate dead.[33] The only other memorial honoring a confederate soldier in Connecticut is the G. W. Smith stone in New London.[34]

Mountain Grove Cemetery in Bridgeport contains an impressive Civil War monument and the graves of 83 veterans of the Union Army.[35]

There are also monuments dedicated to Connecticut soldiers at battle sites in other states, for example, the monument to the 27th Connecticut Infantry at Gettysburg[36] and the Joseph K. F. Mansfield monument at Antietam.[37]

See also

- Category:Connecticut Civil War regiments

- Greenwich in the American Civil War

- List of Connecticut Civil War units

- Category:People of Connecticut in the American Civil War

Notes

- ↑ Connecticut Abolitionism, Connecticuthistory.org a CThumanities Program

- ↑ Underground railroad, Connecticut Freedom Trail and Amistad sites tour in Farmington

- ↑ Warner, Elizabeth, A Pictoral History of Middletown. Norfolk, Virginia: Greater Middletown Preservation Trust, Donning Publishers, 1990.

- ↑ Timeline of Connecticut Slavery

- ↑ 1856 election results

- ↑ Leip, David. "1860 Presidential Election Results". Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. Retrieved October 7, 2008.

- ↑ U.S. Census of 1860.

- ↑ Reitz, Stephanie (2009-11-23). "Group tries to preserve 2 historic Conn. homes". Associate Press. Boston Globe. Retrieved 2010-08-02.

- ↑ Richard F. Miller, ed., States at War: volume 1 (2013) pp 52-57

- ↑ Buckingham, Samuel G., The Life of William A. Buckingham. Springfield, Massachusetts: W. F. Adams Co., 1894.

- ↑ Connecticut Military Department

- ↑ Civil War Archive Retrieved 2008-10-06.

- ↑ Dyer's Compendium.

- ↑ History of Fort Trumbull

- ↑ Stevens, Rev. Henry S., Late Chaplain of the Fourteenth Connecticut Volunteers, 14th Regiment C.V. Infantry.

- ↑ The Knight Hospital

- ↑

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Cousin, John William (1910). A Short Biographical Dictionary of English Literature. London: J. M. Dent & Sons. Wikisource

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Cousin, John William (1910). A Short Biographical Dictionary of English Literature. London: J. M. Dent & Sons. Wikisource - ↑ Croffut & Morris, p. 852.

- ↑ Winchester 1860 Henry Rifle

- ↑ Colt 1861 Navy Model

- ↑ Chase Copper & Brass website and history

- ↑ H. C. Work biography at pdmusic.org

- ↑ Mr. Lincoln's White House: Gideon Welles

- 1 2 Croffut & Morris, pp. 850-51.

- ↑ Eicher, p. 363.

- ↑

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Wilson, James Grant; Fiske, John, eds. (1891). "article name needed". Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Wilson, James Grant; Fiske, John, eds. (1891). "article name needed". Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton.

- ↑

- ↑ New England Civil War Museum

- ↑ Fort Trumbull State Park

- ↑ Connecticut Historical Society: Civil War Monuments, List of Towns.

- 1 2 The Dead Named, Allan Appel, New Haven Independent, May 25, 2009.

- ↑ City of New Haven. Retrieved 2008-10-06.

- ↑ Yale Civil War Memorial

- ↑ MAJOR GENERAL G. W. SMITH STONE

- ↑ Pro Patria: Civil War monument of Connecticut

- ↑ 27th Connecticut Infantry, Gettysburg Monument

- ↑ Update On 2 Connecticut Monuments At Antietam, Paul B. Parvis, Civil War News, August 2002

Further reading

- Cowden, Joanna D. (1983). "The Politics of Dissent: Civil War Democrats in Connecticut". New England Quarterly. 56 (4): 538–554. doi:10.2307/365104. JSTOR 365104.

- Croffut, William A. and John Moses Morris, Military and Civil History of Connecticut During the War of 1861-1865, New York: L. Bill, 1868.

- Dyer, Frederick H., A Compendium of the War of Rebellion: Compiled and Arranged From Official Records of the Federal and Confederate Armies, Reports of the Adjutant Generals of the Several States, The Army Registers and Other Reliable Documents and Sources, Des Moines, Iowa: Dyer Publishing, 1908 (reprinted by Morningside Books, 1978), ISBN 978-0-89029-046-0.

- Hamblen, Charles P., Connecticut Yankees at Gettysburg, (edited By Walter L. Powell), Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press, 1993.

- Hines, Blaikie, Civil War Volunteer Sons of Connecticut, Thomaston, Maine : American Patriot Press, 2002.

- Lane, Jarlath Robert, A Political History of Connecticut During the Civil War, Washington: Catholic University Press, 1941.

- Miller, Richard F. ed. States at War, Volume 1: A Reference Guide for Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont in the Civil War (2013) excerpt

- Niven, John, Connecticut for the Union: The Role of the State in the Civil War, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1965.

- Record of the Service of the Connecticut Men of the Army and Navy of the United States During the War of the Rebellion, Hartford, 1889.

- Talmadge, John E. (1964). "A Peace Movement in Civil War Connecticut". New England Quarterly. 37 (3): 306–321. doi:10.2307/364033. JSTOR 364033.

- Warshauer, Matthew, Connecticut in the American Civil War: Slavery, Sacrifice and Survival, Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press, 2011. ISBN 978-0819573643.

- Warshauer, Matthew, ed. Inside Connecticut and the Civil War: Essays on One State's Struggles (Wesleyan University Press, 2014). Essays by scholars.

External links

- Union Regimental Index, Connecticut, The Civil War Archive.

- Connecticut Men in the Civil War, Connecticut Military Department.