Consistent estimator

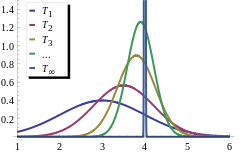

In statistics, a consistent estimator or asymptotically consistent estimator is an estimator—a rule for computing estimates of a parameter θ0—having the property that as the number of data points used increases indefinitely, the resulting sequence of estimates converges in probability to θ0. This means that the distributions of the estimates become more and more concentrated near the true value of the parameter being estimated, so that the probability of the estimator being arbitrarily close to θ0 converges to one.

In practice one constructs an estimator as a function of an available sample of size n, and then imagines being able to keep collecting data and expanding the sample ad infinitum. In this way one would obtain a sequence of estimates indexed by n, and consistency is a property of what occurs as the sample size “grows to infinity”. If the sequence of estimates can be mathematically shown to converge in probability to the true value θ0, it is called a consistent estimator; otherwise the estimator is said to be inconsistent.

Consistency as defined here is sometimes referred to as weak consistency. When we replace convergence in probability with almost sure convergence, then the estimator is said to be strongly consistent. Consistency is related to bias; see bias versus consistency.

Definition

Loosely speaking, an estimator Tn of parameter θ is said to be consistent, if it converges in probability to the true value of the parameter:[1]

A more rigorous definition takes into account the fact that θ is actually unknown, and thus the convergence in probability must take place for every possible value of this parameter. Suppose {pθ: θ ∈ Θ} is a family of distributions (the parametric model), and Xθ = {X1, X2, … : Xi ~ pθ} is an infinite sample from the distribution pθ. Let { Tn(Xθ) } be a sequence of estimators for some parameter g(θ). Usually Tn will be based on the first n observations of a sample. Then this sequence {Tn} is said to be (weakly) consistent if [2]

This definition uses g(θ) instead of simply θ, because often one is interested in estimating a certain function or a sub-vector of the underlying parameter. In the next example we estimate the location parameter of the model, but not the scale:

Examples

Sample mean of a normal random variable

Suppose one has a sequence of observations {X1, X2, …} from a normal N(μ, σ2) distribution. To estimate μ based on the first n observations, one can use the sample mean: Tn = (X1 + … + Xn)/n. This defines a sequence of estimators, indexed by the sample size n.

From the properties of the normal distribution, we know the sampling distribution of this statistic: Tn is itself normally distributed, with mean μ and variance σ2/n. Equivalently, has a standard normal distribution:

as n tends to infinity, for any fixed ε > 0. Therefore, the sequence Tn of sample means is consistent for the population mean μ.

Establishing consistency

The notion of asymptotic consistency is very close, almost synonymous to the notion of convergence in probability. As such, any theorem, lemma, or property which establishes convergence in probability may be used to prove the consistency. Many such tools exist:

- In order to demonstrate consistency directly from the definition one can use the inequality [3]

the most common choice for function h being either the absolute value (in which case it is known as Markov inequality), or the quadratic function (respectively Chebyshev's inequality).

- Another useful result is the continuous mapping theorem: if Tn is consistent for θ and g(·) is a real-valued function continuous at point θ, then g(Tn) will be consistent for g(θ):[4]

- Slutsky’s theorem can be used to combine several different estimators, or an estimator with a non-random convergent sequence. If Tn →dα, and Sn →pβ, then [5]

- If estimator Tn is given by an explicit formula, then most likely the formula will employ sums of random variables, and then the law of large numbers can be used: for a sequence {Xn} of random variables and under suitable conditions,

- If estimator Tn is defined implicitly, for example as a value that maximizes certain objective function (see extremum estimator), then a more complicated argument involving stochastic equicontinuity has to be used.[6]

Bias versus consistency

Bias is related to consistency as follows: a sequence of estimators is consistent if and only if it converges to a value and the bias converges to zero. Consistent estimators are convergent and asymptotically unbiased (hence converge to the correct value): individual estimators in the sequence may be biased, but the overall sequence still consistent, if the bias converges to zero. Conversely, if the sequence does not converge to a value, then it is not consistent, regardless of whether the estimators in the sequence are biased or not.

Unbiased but not consistent

An estimator can be unbiased but not consistent. For example, for an iid sample {x

1,..., x

n} one can use T(X) = x

1 as the estimator of the mean E[x]. Note that here the sampling distribution of T is the same as the underlying distribution (for any n, as it ignores all points but the first), so E[T(X)] = E[x] and it is unbiased, but it does not converge to any value.

However, if a sequence of estimators is unbiased and converges to a value, then it is consistent, as it must converge to the correct value.

Biased but consistent

Alternatively, an estimator can be biased but consistent. For example if the mean is estimated by it is biased, but as , it approaches the correct value, and so it is consistent.

Important examples include the sample variance and sample standard deviation. Without Bessel's correction (using the sample size n instead of the degrees of freedom n − 1), these are both negatively biased but consistent estimators. With the correction, the unbiased sample variance is unbiased, while the corrected sample standard deviation is still biased, but less so, and both are still consistent: the correction factor converges to 1 as sample size grows.

See also

- Efficient estimator

- Fisher consistency — alternative, although rarely used concept of consistency for the estimators

- Regression dilution

- Statistical hypothesis testing

Notes

- ↑ Amemiya 1985, Definition 3.4.2.

- ↑ Lehman & Casella 1998, p. 332.

- ↑ Amemiya 1985, equation (3.2.5).

- ↑ Amemiya 1985, Theorem 3.2.6.

- ↑ Amemiya 1985, Theorem 3.2.7.

- ↑ Newey & McFadden 1994, Chapter 2.

References

- Amemiya, Takeshi (1985). Advanced econometrics. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-00560-0.

- Lehmann, E. L.; Casella, G. (1998). Theory of Point Estimation (2nd ed.). Springer. ISBN 0-387-98502-6.

- Newey, W.; McFadden, D. (1994). Large sample estimation and hypothesis testing. In “Handbook of Econometrics”, Vol. 4, Ch. 36. Elsevier Science. ISBN 0-444-88766-0.

- Nikulin, M.S. (2001), "Consistent estimator", in Hazewinkel, Michiel, Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4