Constitutional Act 1791

|

| |

| Long title | An Act to repeal certain Parts of an Act, passed in the fourteenth Year of his Majesty's Reign, intituled, An Act for making more effectual Provision for the Government of the Province of Quebec, in North America; and to make further Provision for the Government of the said Province. |

|---|---|

| Citation | 31 Geo 3 c 31 |

The Clergy Endowments (Canada) Act 1791 (31 Geo 3 c 31), commonly known as the Constitutional Act 1791,[2] is an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain.

History

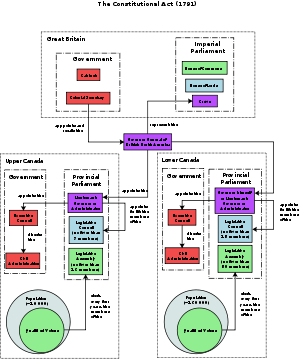

The Act reformed the government of the province of Quebec to accommodate the 10,000 English-speaking settlers, known as the United Empire Loyalists, who had arrived from the United States following the American Revolution. Quebec, with a population of 145,000 French-speaking Canadians, was divided in two when the Act took effect on 26 December 1791. The western half became Upper Canada (now southern Ontario) and the eastern half Lower Canada (now southern Quebec). The names Upper and Lower Canada were given according to their location on the St. Lawrence River. Upper Canada received English law and institutions, while Lower Canada retained French civil law and institutions, including feudal land tenure, and the privileges accorded to the Roman Catholic Church. Representative governments were established in both colonies with the creation of respective legislative assemblies; Quebec had not previously had representative government. Along with each assembly was an appointed upper house, the Legislative Council, created for wealthy landowners; within the Legislative Council was the Executive Council, acting as a cabinet for the governor.

The Constitutional Act tried to create an established church by creating clergy reserves, that is, grants of land reserved for the support of the Protestant clergy.

In practice, income from the rent or sale of these reserves, which constituted one-seventh of the territory of Upper and Lower Canada, went exclusively to the Church of England and, from 1824 on, the Church of Scotland. These reserves created many difficulties in later years, making economic development difficult and creating resentment against the Anglican church, the Family Compact, and the Château Clique. The act was problematic for both English and French speakers; the French Canadians felt they might be overshadowed by Loyalist settlements and increased rights for Protestants, while the new English-speaking settlers felt the French still had too much power. However, both groups preferred the act and the institutions it created to the Quebec Act which it replaced.

The Act of 1791 is often seen as a watershed in the development of French Canadian nationalism as it provided for a province (Lower Canada) which the French considered to be their own, separate from the English-speaking Upper Canada. The disjuncture between this French-Canadian ideal of Lower Canada as a distinct, national homeland and the reality of continued Anglo-Canadian political and economic dominance of the province after 1791 led to discontent and a desire for reform among various segments of the French Canadian populace. The frustration of the French over the nature of Lower Canadian political and economic life in "their" province eventually helped fuel the Lower Canada Rebellion of 1837–38.

See also

References

- ↑ The citation of this Act by this short title was authorised by section 1 of, and Schedule 1 to the Short Titles Act 1896. Due to the repeal of those provisions, it is now authorised by section 19(2) of the Interpretation Act 1978.

- ↑ William Paul McClure Kennedy. Documents of the Canadian Constitution: 1759-1915. Oxford University Press. 1918. p 207.

.svg.png)