Coronal radiative losses

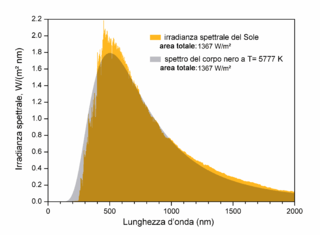

In astronomy and in astrophysics, for radiative losses of the solar corona, it is meant the energy flux irradiated from the external atmosphere of the Sun (traditionally divided into chromosphere, transition region and corona), and, in particular, the processes of production of the radiation coming from the solar corona and transition region, where the plasma is optically-thin. On the contrary, in the chromosphere, where the temperature decreases from the photospheric value of 6000 K to the minimum of 4400 K, the optical depth is about 1, and the radiation is thermal.

The corona extends much further than a solar radius from the photosphere and looks very complex and inhomogeneous in the X-rays images taken by satellites (see the figure on the right taken by the XRT on board Hinode). The structure and dynamics of the corona are dominated by the solar magnetic field. There are strong evidences that even the heating mechanism, responsible for its high temperature of million degrees, is linked to the magnetic field of the Sun.

The energy flux irradiated from the corona changes in active regions, in the quiet Sun and in coronal holes; actually, part of the energy is irradiated outwards, but approximately the same amount of the energy flux is conducted back towards the chromosphere, through the steep transition region. In active regions the energy flux is about 107 erg cm−2sec−1, in the quiet Sun it is roughly 8 105 – 106 erg cm−2sec−1, and in coronal holes 5 105 - 8 105 erg cm−2sec−1, including the losses due to the solar wind. [1] The required power is a small fraction of the total flux irradiated from the Sun, but this energy is enough to maintain the plasma at the temperature of million degrees, since the density is very low and the processes of radiation are different from those occurring in the photosphere, as it is shown in detail in the next section.

Processes of radiation of the solar corona

The electromagnetic waves coming from the solar corona are emitted mainly in the X-rays. This radiation is not visible from the Earth because it is filtered by the atmosphere. Before the first rocket missions, the corona could be observed only in white light during the eclipses, while in the last fifty years the solar corona has been photographed in the EUV and X-rays by many satellites (Pioneer 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, Helios, Skylab, SMM, NIXT, Yohkoh, SOHO, TRACE, Hinode).

The emitting plasma is almost completely ionized and very light, its density is about 10−16 - 10−14 g/cm3. Particles are so isolated that almost all the photons can leave the Sun's surface without interacting with the matter above the photosphere: in other words, the corona is transparent to the radiation and the emission of the plasma is optically-thin. The Sun's atmosphere is not the unique example of X-ray source, since hot plasmas are present wherever in the Universe: from stellar coronae to thin galactic halos. These stellar environments are the subject of the X-ray astronomy.

In an optically-thin plasma the matter is not in thermodynamical equilibrium with the radiation, because collisions between particles and photons are very rare, and, as a matter of fact, the square root mean velocity of photons, electrons, protons and ions is not the same: we should define a temperature for each of these particle populations. The result is that the emission spectrum does not fit the spectral distribution of a blackbody radiation, but it depends only on those collisional processes which occur in a very rarefied plasma.

While the Fraunhofer lines coming from the photosphere are absorption lines, principally emitted from ions which absorb photons of the same frequency of the transition to an upper energy level, coronal lines are emission lines produced by metal ions which had been excited to a superior state by collisional processes. Many spectral lines are emitted by highly ionized atoms, like calcium and iron, which have lost most of their external electrons; these emission lines can be formed only at certain temperatures, and therefore their individuation in solar spectra is sufficient to determine the temperature of the emitting plasma.

Some of these spectral lines can be forbidden on the Earth: in fact, collisions between particles can excite ions to metastable states; in a dense gas these ions immediately collide with other particles and so they de-excite with an allowed transition to an intermediate level, while in the corona it is more probable that this ion remains in its metastable state, until it encounters a photon of the same frequency of the forbidden transition to the lower state. This photon induces the ion to emit with the same frequency by stimulated emission. Forbidden transitions from metastable states are often called as satellite lines.

The Spectroscopy of the corona allows the determination of many physical parameters of the emitting plasma. Comparing the intensity in lines of different ions of the same element, temperature and density can be measured with a good approximation: the different states of ionization are regulated by the Saha equation. The Doppler shift gives a good measurement of the velocities along the line of sight but not in the perpendicular plane. The line width should depend on the Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution of velocities at the temperature of line formation (thermal line broadening), while it is often larger than predicted. The widening can be due to pressure broadening, when collisions between particles are frequent, or it can be due to turbulence: in this case the line width can be used to estimate the macroscopic velocity also on the Sun's surface, but with a great uncertainty. The magnetic field can be measured thanks to the line splitting due to the Zeeman effect.

Optically-thin plasma emission

The most important processes of radiation for an optically-thin plasma [2] [3] [4] are

- the emission in resonance lines of ionized metals (bound-bound emission);

- the radiative recombinations (free-bound radiation) due to the most abundant coronal ions;

- for very high temperatures above 10 MK, the bremsstrahlung (free-free emission).

Therefore, the radiative flux can be expressed as the sum of three terms:

where is the number of electrons per unit volume, the ion number density, the Planck constant, the frequency of the emitted radiation corresponding to the energy jump , the coefficient of collisional de-excitation relative to the ion transition, the radiative losses for plasma recombination and the bremsstrahlung contribution.

The first term is due to the emission in every single spectral line. With a good approximation, the number of occupied states at the superior level and the number of states at the inferior energy level are given by the equilibrium between collisional excitation and spontaneous emission

where is the transition probability of spontaneous emission.

The second term is calculated as the energy emitted per unit volume and time when free electrons are captured from ions to recombinate into neutral atoms (dielectronic capture).

The third term is due to the electron scattering by protons and ions because of the Coulomb force: every accelerated charge emits radiation according to classical elettrodynamics. This effect gives an appreciable contribution to the continuum spectrum only at the highest temperatures, above 10 MK.

Taking into account all the dominant radiation processes, including satellite lines from metastable states, the emission of an optically-thin plasma can be expressed more simply as

where depends only on the temperature. In fact, all the radiation mechanisms require collisional processes and basically depend on the squared density (). The integral of the squared density along the line of sight is called emission measure and is often used in X-ray astronomy. The function has been modeled by many authors but many discrepancies are still in these calculations: differences derive essentially on the spectral lines they include in their models and on the atomic parameters they use.

In order to calculate the radiative flux from an optically-thin plasma, it can be used the linear fitting applied to some model calculations by Rosner et al. (1978) .[5] In c.g.s. unit, in erg cm3 s−1, the function P(T) can be approximated as:

Other related articles

References

- ↑ Withbroe, George L. (1988). "The temperature structure, mass, and energy flow in the corona and inner solar wind". The Astrophysical Journal. 325: 442–467. Bibcode:1988ApJ...325..442W. doi:10.1086/166015.

- ↑ Landini, M.; Monsignori Fossi, B. (1970). "Computation of solar X-ray emission in the region 1-100 Å for Te from 1 MK to 100 MK". Mem. SAIT. 41: 467L. Bibcode:1970MmSAI..41..467L.

- ↑ Raymond, J. C.; Smith, B. W., J. C.; Smith, B. W. (1977). "Soft X-ray spectrum of a hot plasma". The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. 35: 419–439. Bibcode:1977ApJS...35..419R. doi:10.1086/190486.

- ↑ Gronenschild, E. H. B. M.; Mewe, R. (1978). "Calculated X-radiation from optically thin plasmas. III – Abundance effects on continuum emission". The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. 32: 283–305. Bibcode:1978A&AS...32..283G.

- ↑ Rosner, R., Tucker, W.H., Vaiana, G.S., R.; Tucker, W. H.; Vaiana, G. S. (1978). "Dynamics of the quiescent solar corona". The Astrophysical Journal. 220: 643–665. Bibcode:1978ApJ...220..643R. doi:10.1086/155949.

Bibliography

- Güdel M (2004). "X-ray astronomy of stellar coronae" (PDF). Astron Astrophys Rev. 12 (2–3): 71–237. arXiv:astro-ph/0406661

. Bibcode:2004A&ARv..12...71G. doi:10.1007/s00159-004-0023-2.

. Bibcode:2004A&ARv..12...71G. doi:10.1007/s00159-004-0023-2. - Tucker W. H. (1977). Radiation processes in Astrophysics. MIT Press. ISBN 0262700107.