Dacarbazine

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /dəˈkɑːrbəˌziːn/ |

| Trade names | DTIC-Dome |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682750 |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | IV |

| ATC code | L01AX04 (WHO) |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 100% (IV) |

| Metabolism | Extensive |

| Biological half-life | 5 hours |

| Excretion | Renal (40% as unchanged dacarbazine) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

4342-03-4 |

| PubChem (CID) | 2942 |

| DrugBank |

DB00851 |

| ChemSpider |

10481959 |

| UNII |

7GR28W0FJI |

| KEGG |

C06936 |

| ChEBI |

CHEBI:4305 |

| ChEMBL |

CHEMBL476 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C6H10N6O |

| Molar mass | 182.18 g/mol |

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image |

| |

| |

| | |

Dacarbazine (brand names DTIC, DTIC-Dome; also known as DIC or imidazole carboxamide) is an antineoplastic chemotherapy drug used in the treatment of various cancers, among them malignant melanoma, Hodgkin's lymphoma, sarcoma, and islet cell carcinoma of the pancreas.

Dacarbazine is a member of the class of alkylating agents, which destroy cancer cells by adding an alkyl group (CnH2n+1) to its DNA.

Dacarbazine is normally administered by intravenous infusion (IV) under the immediate supervision of a doctor or nurse. Dacarbazine is bioactivated in liver by demethylation to "MTIC" and then to diazomethane, which is an alkylating agent.

It is on the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines, the most important medications needed in a basic health system.[1]

Medical uses

As of mid-2006, dacarbazine is commonly used as a single agent in the treatment of metastatic melanoma,[2][3] and as part of the ABVD chemotherapy regimen to treat Hodgkin's lymphoma,[4] and in the MAID regimen for sarcoma.[5][6] Dacarbazine was proven to be just as efficacious as procarbazine[7] in the German trial for paediatric Hodgkin's lymphoma, without the teratogenic effects. Thus COPDAC has replaced the former COPP regime in children for TG2 & 3 following OEPA.[8]

Side effects

Like many chemotherapy drugs, dacarbazine may have numerous serious side effects, because it interferes with normal cell growth as well as cancer cell growth. Among the most serious possible side effects are birth defects to children conceived or carried during treatment; sterility, possibly permanent; or immune suppression (reduced ability to fight infection or disease). Dacarbazine is considered to be highly emetogenic,[9] and most patients will be pre-medicated with dexamethasone and antiemetic drugs like 5-HT3 antagonist (e.g., ondansetron) and/or NK1 receptor antagonist (e.g., aprepitant). Other significant side effects include headache, fatigue and occasionally diarrhea.

The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare has sent out a black box warning and suggests avoiding dacarbazine due to liver problems.[10]

Mechanism of action

Dacarbazine works by methylating guanine at the O-6 and N-7 positions.[11] Guanine is one of the four nucleotides that makes up DNA. The alkylated DNA strands stick together such that cell division becomes impossible. This affects cancer cells more than healthy cells because cancer cells divide faster. Unfortunately however, some of the healthy cells will still be damaged.

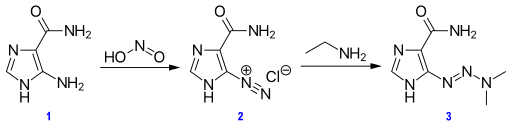

Synthesis

History

Dacarbazine was developed by Y. Fulmer Shealy, Phd at Southern Research Institute in Birmingham, Alabama. Research was funded by a U.S. federal grant. Dacarbazine gained FDA approval in May 1975 as DTIC-Dome. The drug was initially marketed by Bayer.

Experimental use

The combination dacarbazine + oblimersen is in clinical trials for advanced melanoma.[12]

Suppliers

Bayer continues to supply DTIC-Dome. There are also generic versions of dacarbazine available from APP, Bedford, Mayne Pharma (now Hospira) and Teva.

See also

References

- ↑ "19th WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (April 2015)" (PDF). WHO. April 2015. Retrieved May 10, 2015.

- ↑ Serrone, L; Zeuli, M; Sega, FM; Cognetti, F (March 2000). "Dacarbazine-based chemotherapy for metastatic melanoma: thirty-year experience overview.". Journal of experimental & clinical cancer research : CR. 19 (1): 21–34. PMID 10840932.

- ↑ Bhatia, S; Tykodi, SS; Thompson, JA (May 2009). "Treatment of metastatic melanoma: an overview.". Oncology (Williston Park, N.Y.). 23 (6): 488–96. PMC 2737459

. PMID 19544689.

. PMID 19544689. - ↑ Rueda Domínguez, A; Márquez, A; Gumá, J; Llanos, M; Herrero, J; de Las Nieves, MA; Miramón, J; Alba, E (December 2004). "Treatment of stage I and II Hodgkin's lymphoma with ABVD chemotherapy: results after 7 years of a prospective study.". Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology / ESMO. 15 (12): 1798–804. PMID 15550585.

- ↑ Elias, A; Ryan, L; Aisner, J; Antman, KH (April 1990). "Mesna, doxorubicin, ifosfamide, dacarbazine (MAID) regimen for adults with advanced sarcoma.". Seminars in oncology. 17 (2 Suppl 4): 41–9. PMID 2110385.

- ↑ Pearl, ML; Inagami, M; McCauley, DL; Valea, FA; Chalas, E; Fischer, M (2001). "Mesna, doxorubicin, ifosfamide, and dacarbazine (MAID) chemotherapy for gynecological sarcomas.". International journal of gynecological cancer : official journal of the International Gynecological Cancer Society. 12 (6): 745–8. PMID 12445253.

- ↑ Jelić, S; Babovic, N; Kovcin, V; Milicevic, N; Milanovic, N; Popov, I; Radosavljevic, D (February 2002). "Comparison of the efficacy of two different dosage dacarbazine-based regimens and two regimens without dacarbazine in metastatic melanoma: a single-centre randomized four-arm study.". Melanoma research. 12 (1): 91–8. PMID 11828263.

- ↑ Mauz-Körholz, C; Hasenclever, D; Dörffel, W; Ruschke, K; Pelz, T; Voigt, A; Stiefel, M; Winkler, M; Vilser, C; Dieckmann, K; Karlén, J; Bergsträsser, E; Fosså, A; Mann, G; Hummel, M; Klapper, W; Stein, H; Vordermark, D; Kluge, R; Körholz, D (10 August 2010). "Procarbazine-free OEPA-COPDAC chemotherapy in boys and standard OPPA-COPP in girls have comparable effectiveness in pediatric Hodgkin's lymphoma: the GPOH-HD-2002 study.". Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 28 (23): 3680–6. PMID 20625128.

- ↑ Aoki, S; Iihara, H; Nishigaki, M; Imanishi, Y; Yamauchi, K; Ishihara, M; Kitaichi, K; Itoh, Y (January 2013). "Difference in the emetic control among highly emetogenic chemotherapy regimens: Implementation for appropriate use of aprepitant.". Molecular and clinical oncology. 1 (1): 41–46. doi:10.3892/mco.2012.15. PMC 3956247

. PMID 24649120.

. PMID 24649120. - ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on October 1, 2011. Retrieved August 19, 2011.

- ↑ Kewitz, S; Stiefel, M; Kramm, CM; Staege, MS (January 2014). "Impact of O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) promoter methylation and MGMT expression on dacarbazine resistance of Hodgkin's lymphoma cells.". Leukemia research. 38 (1): 138–43. PMID 24284332.

- ↑ Bedikian, AY; Garbe, C; Conry, R; Lebbe, C; Grob, JJ (June 2014). "Dacarbazine with or without Oblimersen (a Bcl-2 Antisense Oligonucleotide) in Chemotherapy-Naïve Patients with Advanced Melanoma and Low-Normal Serum Lactate Dehydrogenase: the AGENDA Trial". Melanoma Research. 24 (3): 237–43. doi:10.1097/CMR.0000000000000056. PMID 24667300.

- Bibliography