Eyewitness identification

| Evidence |

|---|

| Part of the common law series |

| Types of evidence |

| Relevance |

| Authentication |

| Witnesses |

| Hearsay and exceptions |

| Other common law areas |

In eyewitness identification, in criminal law, evidence is received from a witness "who has actually seen an event and can so testify in court".[1]

Although it has been observed, by the late U.S. Supreme Court Justice William J. Brennan, Jr., in his dissent to Watkins v. Sowders, that witness testimony is evidence that "juries seem most receptive to, and not inclined to discredit".[2] Justice Brennan also observed that "At least since United States v. Wade, 388 U.S. 218 (1967), the Court has recognized the inherently suspect qualities of eyewitness identification evidence, and described the evidence as "notoriously unreliable".[2] The Innocence Project, a non-profit organization which has worked on using DNA evidence in order to reopen criminal convictions that were made before DNA testing was available as a tool in criminal investigations, states that "Eyewitness misidentification is the single greatest cause of wrongful convictions nationwide, playing a role in more than 75% of convictions overturned through DNA testing."[3] In the United Kingdom, the Criminal Law Review Committee, writing in 1971, stated that cases of mistaken identification "constitute by far the greatest cause of actual or possible wrong convictions".[4]

Historically, eyewitness testimony had what Brennan described as "a powerful impact on juries",[2] who noted in his dissent that "All the evidence points rather strikingly to the conclusion that there is almost nothing more convincing [to a jury] than a live human being who takes the stand, points a finger at the defendant, and says 'That's the one!'"[5] Another commentator observed that the eyewitness identification of a person as a perpetrator was persuasive to jurors even when "far outweighed by evidence of innocence."[6]

Known cases of eyewitness error

The Innocence Project has facilitated the exoneration of 214 men who were convicted of crimes they did not commit, as a result of faulty eyewitness evidence.[7] A number of these cases have received substantial attention from the media.

Jennifer Thompson's case is one example: She was a college student in North Carolina in 1984, when a man broke into her apartment, put a knife to her throat, and raped her. According to her own account, Ms. Thompson studied her rapist throughout the incident with great determination to memorize his face. "I studied every single detail on the rapist's face. I looked at his hairline; I looked for scars, for tattoos, for anything that would help me identify him. When and if I survived the attack, I was going to make sure that he was put in prison and he was going to rot."[8]

Ms. Thompson went to the police station later that same day to work up a [composite sketch] of her attacker, relying on what she believed was her detailed memory. Several days later, the police constructed a photographic lineup, and she selected Ronald Junior Cotton from the lineup. She later testified against him at trial. She was positive it was him, without any doubt in her mind. "I was sure. I knew it. I had picked the right guy, and he was going to go to jail. If there was the possibility of a death sentence, I wanted him to die. I wanted to flip the switch."[9]

But she was wrong, as DNA results eventually showed. It turns out she was even presented with her actual attacker during a second trial proceeding a year after the attack, but swore she'd never seen the man before in her life. She remained convinced that Ronald Cotton was her attacker, and it was not until much later, after Mr. Cotton had served 11 years in prison for a crime he did not commit, that she realized that she had made a grave mistake.

Jennifer Thompson's memory had failed her, resulting in a substantial injustice. It took definitive DNA testing to shake her confidence, but she now knows that despite her confidence in her identification, it was wrong. Cases like Ms. Thompson's prompted the emergence of a field within the social sciences dedicated to the study of eyewitness memory and the causes underlying its frequently recurring failures.

Causes of eyewitness error

"System variables" (police procedures)

One of the primary reasons that eyewitnesses to crimes have been shown to make mistakes in their recollection of perpetrator identities, is the police procedures used to collect eyewitness evidence. Various factors have been discovered to make police identification procedures more or less reliable as a test of eyewitness memory, and these procedural mechanisms have been termed "system variables" by social scientists researching this systemic problem.[10] "System variables are those that affect the accuracy of eyewitness identifications and over which the criminal justice system has (or can have) control."[11]

Acknowledging the importance of these procedural precautions recommended by Dr. Gary L. Wells and other leading eyewitness researchers, the Department of Justice published a set of best practices for conducting police lineups in 1999.[12]

Culprit-present versus culprit-absent lineups

One of the most obvious causes of inaccurate identifications resulting from police lineups is the use of a lineup that does not include the actual perpetrator of the crime. In other words, police suspect one person of having committed a crime, when in fact it was committed by an unknown other person who does not appear in the lineup. When the actual perpetrator is not included in the lineup, research has shown that the police suspect faces a significantly heightened risk of being incorrectly identified as the culprit.[13]

According to eyewitness researchers, the most likely cause of this increased occurrence of misidentification is what is termed the "relative judgment" process. That is, when viewing a group of photos or individuals, a witness tends to select the person who looks "most like" the perpetrator. When the actual perpetrator is not present in the lineup, the police suspect is often the person who best fits the description, hence his or her selection for the lineup.

Given the common, good faith occurrence of police lineups that do not include the actual perpetrator of a crime, it becomes particularly critical that other procedural measures are undertaken to minimize the likelihood of an inaccurate identification.

Pre-lineup instructions

Following this finding that eyewitnesses are prone to making "relative judgments" when faced with a lineup that does not contain the actual perpetrator, researchers hypothesized that instructing the witness prior to the lineup might serve to mitigate the occurrence of error. In fact, studies have shown that simply instructing a witness that the perpetrator "may or may not be present" in the lineup can dramatically reduce the likelihood that a witness will identify an innocent person.[14]

"Blind" lineup administration

Eyewitness researchers know that the police lineup is, at center, a psychological experiment designed to test the ability of a witness to recall the identity of the perpetrator of a crime. As such, it is recommended that police lineups be conducted in double-blind fashion, like any scientific experiment, in order to avert the possibility that inadvertent cues from the lineup administrator will suggest the "correct" answer and thereby subvert the independent memory of the witness.[15] The occurrence of "experimenter bias" is well documented across the sciences, and as such, researchers recommend that police lineups be conducted by someone not connected to the case and unaware of the identity of the suspect.

Confidence Judgement

Asking an eyewitness their confidence of their selection with a doubleblind process can improve the accuracy of eyewitness selection.[16][17]

Lineup structure and content

"Known innocent" fillers

Once police have identified a suspect, they will typically place that individual into either a live or photo lineup, along with a set of "fillers." Researchers and the DOJ guidelines recommend, as a preliminary matter, that the fillers be "known innocent" non-suspects. This way, if a witness selects someone other than the suspect, the unreliability of that witness's memory is revealed. In that respect, the lineup procedure serves as a test of the witness's memory, with clear "wrong" answers. If more than one suspect is included in the lineup – as in the 2006 Duke University lacrosse case, for example – then the lineup becomes tantamount to a multiple choice test with no wrong answer.

Filler characteristics

These "known innocent" fillers should be selected to match the original description provided by the witness. If a neutral observer is able to select the suspect from the lineup based on the recorded description by the witness – that is, if the suspect is the only one present who clearly fits the description – then the procedure cannot be relied upon as a test of the witness's memory of the actual perpetrator. Researchers have noted that this rule is particularly important when the witness's description includes unique features, such as tattoos, scars, unusual hairstyles, etc.[18]

Simultaneous versus sequential presentation

Researchers have also suggested that the manner in which photos or individuals chosen for a lineup are presented can also be key to the reliability of an identification. Specifically, leading researchers suggest that lineups should be conducted sequentially, rather than simultaneously. In other words, each member of a given lineup should be presented to a witness by himself, rather than showing a group of photos or individuals to a witness together. According to social scientists, use of this procedure will minimize the effects of the "relative judgment" process discussed above, by encouraging witnesses to compare each person individually to his or her independent memory of the identity of the perpetrator. According to researchers, use of a simultaneous procedure makes it more likely that witnesses will pick the person who merely looks the most like the perpetrator from the group, which introduces an acute danger when the actual perpetrator is not present in the lineup.[19] A pilot study was conducted in Minnesota in 2006 to test this hypothesis, and the results show the sequential procedure to be superior as a means of improving identification accuracy and reducing the occurrence of false identifications.[20]

The "Illinois Report" controversy

In 2005, the Illinois state legislature commissioned a pilot project to test reform measures recommended by social scientists to increase the accuracy and reliability of police identification procedures. The study was conducted by the Chicago police department, and an initial report purported to show that the status quo was superior to procedures recommended by researchers in reducing false identifications, in reliance on their decades of scientific research.[21] The mainstream media spotlighted the report, including a front-page article in the New York Times, suggesting that three decades' worth of otherwise uncontroverted social science had been called into question.[22]

Criticism of the report and its underlying methodology surfaced shortly after its release. One critic averred that "the design of the [Illinois pilot] project contained so many fundamental flaws that it is fair to wonder whether its sole purpose was to inject confusion into the debate about the efficacy of sequential double-blind procedures and to thereby prevent adoption of the reforms."[23] Seeking information on the data and methodology underlying the report, the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers (NACDL) filed a lawsuit under the Freedom of Information Act seeking the unreleased information.[24] That suit remains pending.

In July 2007, a "blue ribbon" panel of eminent psychologists, including one Nobel Laureate, released a report examining the methodology and claims of the Illinois Report, which appears to have confirmed the suspicions of earlier critics. Researchers from Harvard, Princeton, Carnegie Mellon, and other academic institutions examined the study and reported that the study was infected with a fundamental flaw that had "devastating consequences" to its scientific merit, and which "guaranteed that most outcomes would be difficult or impossible to interpret." Their primary critique was an observed "confounding" of variables, rendering it impossible to draw meaningful comparisons between the methods tested.[25]

The confound that the critics of the Illinois study criticized was the following: the Illinois study compared the traditional simultaneous method of lineup presentation with the sequential double-blind method recommended by academics like Gary Wells. The traditional method is not conducted double-blind (meaning that the person presenting the lineup does not know which person or photo is the suspect). The critics claim that the results cannot be compared because one method was not double-blind while the other was double-blind. This criticism ignores the fact that the mandate of the Illinois legislature was to compare the traditional method with the academic method. More significantly, as an experiment to determine whether or not sequential double-blind administration would be superior to the simultaneous methods used by most police departments, the Illinois study provides an abundance of useful data which, at this point, seems to show that neither of the methods used in that experiment is superior to the other. What it does not provide is a clear reason why, because the effect of "double-blind" was not tested for the simultaneous lineups.[26] The Innocence Project Lineup studies mentioned here previously were never funded, largely because the expected grant funds were withdrawn in connection with economic difficulties.[27] A separate grant was submitted to the Department of Justice in March 2009 by the independent Urban Institute to study simultaneous/sequential lineups in actual police departments in Connecticut and Washington, D.C. That study had been solicited by DOJ, but was unexpectedly cancelled in August 2009 due to "a low likelihood of success." It is unclear at this time what the DOJ was thinking when they canceled the grant. The Urban Institute is seeking other funding.[28]

Post-lineup feedback and confidence statements

Any feedback from the lineup administrator following an identification can have a dramatic effect on a witness's sense of his or her own accuracy. A highly tentative "maybe" can be artificially transformed into "100% confident" with a simple comment such as "Good, you identified the actual suspect." Mere preparation for cross-examination, including simply thinking about how to answer questions regarding the identification, has also been shown to artificially inflate an eyewitness's sense of her own level of certainty; the same is true when a witness simply learns that another witness identified the same person. This malleability of eyewitness confidence has been shown to be far more pronounced in cases where the witness turns out to be wrong.[29]

When there is a positive correlation between eyewitness confidence and accuracy, it tends to occur when a witness's confidence is measured immediately following the identification, and prior to any confirming feedback. In keeping with this finding, researchers suggest that a statement of a witness's confidence, in her own words, be taken immediately following an identification. Any future statement of confidence or certainty is widely regarded as unreliable, given the host of intervening factors that have been shown to distort it as time passes.[30]

"Estimator variables" (circumstantial factors)

Social scientists have also identified a set of "estimator variables" – that is, factors connected to the witness herself or to the circumstances surrounding her observation of the individual she would later attempt to identify – that research has shown to make an identification more or less reliable.

Cross-racial identifications

One of the most-studied topics in this area is the cross-racial identification, namely when the witness and the perpetrator are of different races. A recent meta-analysis of 25 years of research shows a definitive, statistically significant "cross-race impairment," where members of any one race have a clear deficiency for accurately identifying members of another race. The effect appears to be true regardless of the races in question. Various hypotheses have been tested to explain this deficiency in identification accuracy, including any racial animosity on the part of the viewer, and exposure level to the other race in question. Racist attitudes have not been observed to have any effect on the impairment; exposure level has been observed to have a minute effect in some studies, yet the cross-race impairment itself has been observed to substantially overshadow all other variables, even when testing people who have been surrounded by members of the other race for their entire lives.[31]

Stress

The effect of stress on eyewitness recall is one of the most widely misunderstood of the factors commonly at play in a crime witness scenario.[32] Studies have consistently shown that the presence of stress has a dramatically negative impact on the accuracy of eyewitness memory, a phenomenon which is often not appreciated by witnesses themselves. In a seminal study on this topic, Yale psychiatrist Charles Morgan and a team of researchers tested the ability of trained, military survival school students to identify their interrogators following low- and high-stress scenarios. In each condition, subjects were face-to-face with an interrogator for 40 minutes in a well-lit room. The following day, each participant was asked to select his or her interrogator out of either a live or photo lineup. In the case of the photo spread – the most common form of police lineup in the U.S. – those subjected to the high-stress scenario falsely identified someone other than the interrogator in 68% of cases, compared to only 12% from the low-stress scenario.[33]

Presence of a weapon

The presence of a weapon has also been shown to diminish the accuracy of eyewitness recall, often referred to as the "weapon-focus effect". This phenomenon has been studied at length by eyewitness researchers, and the findings have consistently demonstrated that eyewitnesses recall the identity of a perpetrator less accurately when a weapon was present during the incident.[34] Eminent psychologist Elizabeth Loftus used eye-tracking technology to monitor this effect, and found that the presence of a weapon draws a witness's visual focus away from other things, such as the perpetrator's face.[35]

Rapid decline of eyewitness memory

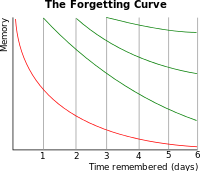

It is thought that memory degrades over time, some researchers state that the rate at which eyewitness memory declines is swift, and the drop-off is sharp, in contrast to the more common view that memory degrades slowly and consistently as time passes. The "forgetting curve" of eyewitness memory has been shown to be "Ebbinghausian" in nature: it begins to drop off sharply within 20 minutes following the initial encoding, and continues to do so exponentially until it begins to level off around the second day at a dramatically reduced level of accuracy.[36] And as noted above, eyewitness memory is increasingly susceptible to contamination as time passes.[37] However, a study unrelated to eyewitness identification in criminal cases reports that individuals have a much better memory for faces than for numbers.[38] This would indicate that not all eyewitness identifications are equal. An identification where the eyewitness clearly saw the face would be more reliable than one based on a combination of factors such as ethnicity, estimated age, estimated height, estimated weight, general body type, hair color, dress, etc.

Other circumstantial factors

A variety of other factors have been observed to affect the reliability of an eyewitness identification. The elderly and young children tend to recall faces less accurately, as compared to young adults. Intelligence, education, gender, and race, on the other hand, appear to have no effect (with the exception of the cross-race effect, as above).[39]

The opportunity that a witness has to view the perpetrator and the level of attention paid have also been shown to affect the reliability of an identification. Attention paid, however, appears to play a more substantial role than other factors like lighting, distance, or duration. For example, when witnesses observe the theft of an item known to be of high value, studies have shown that their higher degree of attention can result in a higher level of identification accuracy (assuming the absence of contravening factors, such as the presence of a weapon, stress, etc.).[40]

The law of eyewitness identification evidence in criminal trials

U.S.

The legal standards addressing the treatment of eyewitness testimony as evidence in criminal trials vary widely across the United States on issues ranging from the admissibility of eyewitness testimony as evidence, the admissibility and scope of expert testimony on the factors affecting its reliability, and the propriety of jury instructions on the same factors. In New Jersey, generally considered a leading court with respect to criminal law, a report was prepared by a special master during a remand proceeding in the case of New Jersey v. Henderson which comprehensively researched published literature and heard expert testimony with respect to eyewitness identification.[41] Based on the master's report the New Jersey court issued a decision on August 22, 2011 which requires closer examination of the reliability of eyewitness testimony by trial courts in New Jersey. Perry v. New Hampshire, a case which raised similar issues, was decided January 11, 2012 by the U.S. Supreme Court.[42] which in an 8–1 decision decided that judicial examination of eye-witness testimony was required only in the case of police misconduct.

Held: The Due Process Clause does not require a preliminary judicial inquiry into the reliability of an eyewitness identification when the identification was not procured under unnecessarily suggestive circumstances arranged by law enforcement.[43]

The preeminent role of the jury in evaluating questionable evidence was cited by the court.[44]

Detectives interrogating children in the court perhaps lack the necessary training to make them effective perhaps “ more work needs to be done in finding effective ways of helping appropriate members of the legal profession to develop skills and understanding in child development and in talking with children”

Admissibility

The federal due process standard governing the admissibility of eyewitness evidence is set forth in the U.S. Supreme Court case of Manson v. Brathwaite. Under the federal standard, if an identification procedure is shown to be unnecessarily suggestive, the court must consider whether certain independent indicia of reliability are present, and if so, weigh those factors against the corrupting effect of the flawed police procedure. Within that framework, the court should determine whether, under the totality of the circumstances, the identification appears to be reliable. If not, the identification evidence must be excluded from evidence under controlling federal precedent.[45]

Certain criticisms have been waged against the Manson standard, however. According to legal scholars, "the rule of decision set out in Manson has failed to meet the Court's objective of furthering fairness and reliability."[46] For example, the Court requires that the confidence of the witness be considered as an indicator of the reliability of the identification evidence. As noted above, however, extensive studies in the social sciences have shown that confidence is unreliable as a predictor of accuracy. Social scientists and legal scholars have also expressed concern that "the [Manson] list as a whole is substantially incomplete," thereby opening the courthouse doors to the admission of unreliable evidence.[47]

Expert testimony

Expert testimony on the factors affecting the reliability of eyewitness evidence is allowed in some U.S. jurisdictions, and not in others. In most states, it is left to the discretion of the trial court judge. States generally allowing it include California, Arizona, Colorado, Hawaii, Tennessee (by a 2007 state Supreme Court decision), Ohio, and Kentucky. States generally prohibiting it include Pennsylvania and Missouri. Many states have less clear guidelines under appellate court precedent, such as Mississippi, New York, New Hampshire, and New Jersey. It is often difficult to tell whether expert testimony has been allowed in a given state, since if the trial court lets the expert testify, there is generally no record created. On the other hand, if the expert is not allowed, that becomes a ground of appeal if the defendant is convicted. That means that most cases that generate appellate records are cases only in which the expert was disallowed (and the defendant was convicted).

In those states where expert testimony on eyewitness reliability is not allowed, it is typically on grounds that the various factors are within the common sense of the average juror, and thus not the proper topic of expert testimony. To further expand jurors are " likely to put faith in the expert's testimony or even to overestimate the significance of results that the expert reports"[48]

Polling data and other surveys of juror knowledge appear to contradict this proposition, however, revealing substantial misconceptions on a number of discrete topics that have been the subject of significant study by social scientists.[49]

Jury instructions

Criminal defense lawyers often propose detailed jury instructions as a mechanism to offset undue reliance on eyewitness testimony, when factors shown to undermine its reliability are present in a given case. Many state courts prohibit instructions detailing specific eyewitness reliability factors but will allow a generic instruction, while others find detailed instructions on specific factors to be critical to a fair trial. California allows instructions when police procedures are in conflict with established best practices, for example, and New Jersey mandates an instruction on the cross-race effect when the identification is central to the case and uncorroborated by other evidence.[50]

Although instructions informing jurors of certain eyewitness identification mistakes are a plausible solution , recent discoveries in research have shown that this gives a neutral effect, "studies suggest that general jury instructions informing jurors of the unreliability of eyewitness identifications are not effective in helping jurors to evaluate the reliability of the identification before them"[51]

England and Wales

PACE Code D

Most identification procedures are regulated by Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 Code D.

Where there is a particular suspect

In any cases where identification may be an issue, a record must be made of the description of the suspect first given by a witness. This should be disclosed to the suspect or his solicitor. If the ability of a witness to make a positive visual identification is likely to be an issue, one of the formal identification procedures in Pace Code D, para 3.5–3.10 should be used, unless it would serve no useful purpose (e.g. because the suspect was known to the witnesses or if there was no reasonable possibility that a witness could make an identification at all).

The formal identification procedures are:

- Video identification

- Identification parade If it is more practicable and suitable than video identification, an identification parade may be used.

- Group identification If it is more suitable than video identification or an identification parade, the witness may be asked to pick a person out after observing a group.

- Confrontation If the other methods are unsuitable, the witness may be asked whether a certain person is the person they saw.

Where there is no particular suspect

If there is no particular suspect, a witness may be shown photographs or be taken to a neighbourhood in the hope that he recognises the perpetrator. Photographs should be shown to potential witnesses individually (to prevent collusion) and once a positive identification has been made, no other witnesses should be shown the photograph of the suspect.

Breaches of PACE Code D

Under s. 78 of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984, the trial judge may exclude evidence if it would have an adverse effect on the fairness of the proceedings if it were admitted. Breach of Code D does not automatically mean that the evidence will be excluded, but the judge should consider whether a breach has occurred and what the effect of the breach was on the defendant. If a judge decides to admit evidence where there has been a breach, he should give reasons.[52] and in a jury trial, the jury should normally be told "that an identification procedure enables suspects to put the reliability of an eye-witness’s identification to the test, that the suspect has lost the benefit of that safeguard, and that they should take account of that fact in their assessment of the whole case, giving it such weight as they think fit".[53] Informal identifications made through social media such as Facebook (often in breach of Code D), pose particular problems for the criminal courts.[54] [55]

Turnbull directions

Where the identification of the defendant is in issue (not merely the honesty of the identifier or the fact that the defendant matched a particular description), and the prosecution rely substantially or wholly on the correctness of one or more identifications of the defendant, the judge should give a direction[56] to the jury:[57]

- The judge should warn the jury of the special need for caution before convicting the accused in reliance on the correctness of the identification or identifications. In addition he should instruct them as to the reason for the need for such a warning and should make some reference to the possibility that a mistaken witness can be a convincing one and that a number of such witnesses can all be mistaken.

- The judge should direct the jury to examine closely the circumstances in which the identification by each witness came to be made and remind the jury of any specific weaknesses in the identification evidence. If the witnesses recognised a known defendant, the judge should remind the jury that mistakes even in the recognition of relatives or close friends are sometimes made.

- When, in the judgment of the trial judge, the quality of the identifying evidence is poor, as for example when it depends solely on a fleeting glance or on a longer observation made in difficult conditions, the judge should withdraw the case from the jury and direct an acquittal unless there is other evidence which goes to support the correctness of the identification.

- The trial judge should identify to the jury the evidence which he adjudges is capable of supporting the evidence of identification. If there is any evidence or circumstances which the jury might think was supporting when it did not have this quality, the judge should say so...

Reform efforts

U.S.

Largely in response to the mounting list of wrongful convictions discovered to have resulted from faulty eyewitness evidence, an effort is gaining momentum in the United States to reform police procedures and the various legal rules addressing the treatment of eyewitness evidence in criminal trials. Social scientists are committing more resources to studying and understanding the mechanisms of human memory in the eyewitness context, and lawyers, scholars, and legislators are devoting increasing attention to the fact that faulty eyewitness evidence remains the leading cause of wrongful conviction in the United States.

Reform measures mandating that police use established best practices when collecting eyewitness evidence have been implemented in New Jersey, North Carolina, Wisconsin, West Virginia, and Minnesota. Bills on the same topic have been proposed in Georgia, New Mexico, California, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New York, Vermont, and others.[58]

- Department of Justice Guidelines for Conducting Lineup Procedures

- NLADA resource on Eyewitness ID Issues

- Website of eyewitness researcher Dr. Gary Wells

- Dr. Steven Penrod's website, with links to substantial eyewitness ID research

- Dr. Nancy Steblay's website, with links to substantial eyewitness ID research

- NACDL's Eyewitness ID Resource page

- Dr. Roy Malpass's Eyewitness ID Research Laboratory Website

- Dr. Solomon Fulero's website, with links to relevant documents

- American Psychology-Law Society's page on eyewitness ID publications

See also

References

- ↑ Law.com Legal Dictionary Online

- 1 2 3 Watkins v. Sowders, 449 U.S. 341 (1980)

- ↑ "Eyewitness Misidentification".

- ↑ Criminal Law Review Committee Eleventh Report, Cmnd 4991

- ↑ Watkins v. Souders, 449 U.S. 341, 352 (1982) (Brennan, J. dissenting).

- ↑ Elizabeth Loftus, Eyewitness Evidence 9 (1979).

- ↑ See www.innocenceproject.org, mouse over "Know the Cases," then click "Search Profiles," then search cases with "Eyewitness Misidentification" as the Contributing Cause.

- ↑ Jennifer Thompson, 'I Was Certain, but I Was Wrong,' June 18, 2000, New York Times. (Archived here.)

- ↑ Id.

- ↑ See, e.g. Gary Wells & Elizabeth Olson, Eyewitness Testimony, 54 Annu. Rev. Psychol. 277 (2003).

- ↑ Id. at 285.

- ↑ Eyewitness Evidence, A Guide For Law Enforcement (pdf), United States Department of Justice (Oct. 1999)

- ↑ Wells & Olson, supra note 4, at 286.

- ↑ See, e.g., Gary Wells et al., Eyewitness Identification Procedures: Recommendations for Lineups and Photospreads, 22 L. & Hum. Behavior 603, 613 (1998).

- ↑ Id. at 623.

- ↑ Greenwood, Veronique. "Are You Sure That's the Guy?". Scientific American Mind. 27 (3): 17–17. doi:10.1038/scientificamericanmind0516-17.

- ↑ Wixted, John T.; Mickes, Laura; Dunn, John C.; Clark, Steven E.; Wells, William (2016-01-12). "Estimating the reliability of eyewitness identifications from police lineups". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 113 (2): 304–309. doi:10.1073/pnas.1516814112. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 4720310

. PMID 26699467.

. PMID 26699467. - ↑ See id. at 625-26.

- ↑ See Wells et al., supra note 11, at 614–15.

- ↑ Amy Klobuchar et al., Improving Eyewitness Identifications: Hennepin County's Blind Sequential Lineup Pilot Project, 4 Cardozo Pub. L. Pol. & Ethics J. 381 (2006), available here (pdf).

- ↑ Report to the Legislature of the State of Illinois: The Illinois Pilot Program on Sequential Double-Blind Identification Procedures ("Illinois Report"), available here (pdf); Addendum to Illinois Report available here (pdf).

- ↑ Kate Zernike, "Study Fuels Debate Over Police Lineups," N.Y. Times, April 19, 2006, available here.

- ↑ Timothy P. O'Toole, What's the Matter With Illinois? How an Opportunity Was Squandered to Conduct an Important Study on Eyewitness Identification Procedures, Champion 16 (August 2006), available here.

- ↑ Press Release, "National Legal Group Files Lawsuit Challenging Illinois Police Defense of Traditional Lineups," NACDL, Feb. 8, 2007, available here.

- ↑ Daniel L. Schachter et al., Policy Forum: Studying Eyewitness Investigations in the Field, L. Hum. Behavior (July 2007), available here (pdf).

- ↑ Mecklenberg, Bailey, Larson, The Illinois Field Study: A Significant Contribution to Understanding Real World Eyewitness Identification Issues, 32 Law & Human Behavior (2008)22–27

- ↑ Conversation with Barry Scheck, January 2009

- ↑ Personal knowledge: The author of this note (Assistant State's Attorney James Clark) is working with the Urban Institute by coordinating cooperation of Connecticut police departments in the study.

- ↑ See, e.g., Amy Bradfield et al., The Damaging Effect of Confirming Feedback on the Relation Between Eyewitness Certainty and Identification Accuracy, 87 J. Applied Psychol. 112 (2002).

- ↑ Wells et al., supra note 11, 629–30.

- ↑ Christian A. Meissner & John A. Brigham, Thirty Years of Investigating the Own-Race Bias in Memory for Faces: A Meta-Analytic Review, 7 Psychol. Pub. Policy & L. 3 (2001).

- ↑ See Schmechel et al., Beyond the Ken? Testing Jurors' Understanding of Eyewitness Evidence, 46 Jurimetrics 177, 197 (2006) (citing poll finding over two-thirds of potential District of Columbia jurors do not understand the effects of stress on memory), available here; see also Timothy P. O'Toole, District of Columbia Public Defender Survey: What Do Jurors Understand About Eyewitness Reliability?, Champion 28 (April 2005), available here.

- ↑ Charles A. Morgan III et al., Accuracy of Eyewitness Memory for Persons Encountered During Exposure to Highly Intense Stress, 27 Int'l J.L. & Psychiatry 265, 272 (2004).

- ↑ Nancy Mehrkens Steblay, A Meta-Analytic Review of the Weapon Focus Effect, 16 L. & Hum. Behav. 413 (1992), available here (pdf).

- ↑ Elizabeth F. Loftus et al., Some Facts About "Weapon Focus," 11 L. & Hum. Behav. 55 (1987)

- ↑ See, e.g. Gary Wells et al., supra note 11, at 621–22; Herman Ebbinghaus, Memory: A Contribution to Experimental Psychology (1885/1913); Kassin et al., On the "General Acceptance" of Eyewitness Testimony Research: A New Survey of the Experts, 56 Amer. Psychologist 405, 413–14 (2001) (finding a "strong consensus" among researchers on the sharp and rapid decline of eyewitness memory)

- ↑ M.P. Gerrie et al., False Memories, in PSYCHOLOGY AND LAW: AN EMPIRICAL PERSPECTIVE (Neil Brewer & Kip Williams, eds., forthcoming 2007) ("We have known for over 100 years that memories fade, sometimes rapidly, in a function known as the forgetting curve.... [and] that as memories fade, they also become more susceptible to suggestion.").

- ↑ Hiroaki Kikuchi & Shohachiro Nakanishi, Can We Remember Faces Much Easier Than Numbers? – available at https://www.cs.dm.u-tokai.ac.jp/Publication/csv/pdfs/hypothesis-afss.pdf

- ↑ See Wells et al., supra note 4, 280–81.

- ↑ Id. at 282.

- ↑ Geoffrey Gaulkin (June 18, 2010). "Report of the Special Master" (report of a special master). New Jersey v. Henderson. Supreme Court of New Jersey. Retrieved August 25, 2011.

- ↑ Weiser, Benjamin (August 24, 2011). "In New Jersey, Rules Are Changed on Witness IDs". The New York Times. Retrieved August 25, 2011.

troubling lack of reliability in eyewitness identifications

- ↑ Syllabus author is anonymous; decision, joined by 6 other justices, was delivered by Ruth Bader Ginsburg with Justice Thomas concurring and Justice Sotomayor dissenting. "Perry v. New Hampshire" (Slip opinion). United States Supreme Court. p. Syllabus. Retrieved January 12, 2012.

- ↑ Adam Liptak (January 11, 2012). "Eyewitness Evidence Needs No Special Cautions, Court Says". The New Yort Times. Retrieved January 12, 2012.

- ↑ Manson, 432 U.S. 98 (1977).

- ↑ See, e.g., Timothy O'Toole & Giovanna Shay, Manson v. Brathwaite Revisited: Toward a New Rule of Decision For Due Process Challenges to Eyewitness Identification Procedures, 41 Valparaiso L. Rev. 109 (2006).

- ↑ See id. at 113; Gary Wells, What is Wrong With the Manson v. Brathwaite Test of Eyewitness Identification Accuracy?, available here.

- ↑ Walker, Suedabeh (2013). "Drawing on Daubert: Bringing Reliability to the Forefront in the Admissibility of Eyewitness Identification Testimony". Emory Law Journal. 62.4: 1205–1242 – via heinonline.

- ↑ See, e.g., Schmechel et al., supra note 17; Benton et al., Eyewitness Memory is Still Not Common Sense: Comparing Jurors, Judges and Law Enforcement to Eyewitness Experts, 20 Applied Cognitive Psychol. 115 (2006).

- ↑ State v. Cromedy, 727 A.2d 457 (N.J. 1999), available here.

- ↑ Walker, Suedabeh (2013). "Drawing on Daubert: Bringing Reliability to the Forefront in the Admissibility of Eyewitness Identification Testimony.". Emory Law Journal. 62(4): 1205–1242 – via heinonline.

- ↑ R v. Allen, Crim LR 643 (1995).

- ↑ R v. Z, Crim LR 174 (Court of Appeal (Criminal Division), Potter LJ 2003).

- ↑ Mack, Jon; Sampson, Richard (2 February 2013). "Facebook Identifications". Criminal Law & Justice. 177: 77.

- ↑ R v McCullough [2011] EWCA Crim 1413; Alexander and McGill [2012] EWCA Crim 2768; DZ and JZ [2012] EWCA Crim 1845

- ↑ See the specimen direction of the Judicial Studies Board.

- ↑ R v. Turnbull [1977] QB 224

- ↑ See NACDL's page outlining state-by-state legislative reform efforts, found here.

External links

- The Illinois Field Study: A Significant Contribution to Understanding Real World Eyewitness Identification Issues: The original journal article of the "Illinois Report" by S.H. Mecklenburg et al.

- Examining the Responses to the Illinois Study on Double-Blind Sequential Lineup Procedures: Critical evaluation of the "Illinois Report" by Zack L. Winzeler.