Farmville, Virginia

| Farmville, Virginia | |

|---|---|

| Town | |

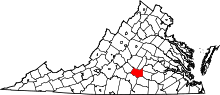

|

Location of Farmville, Virginia | |

| Coordinates: 37°17′52″N 78°23′45″W / 37.29778°N 78.39583°WCoordinates: 37°17′52″N 78°23′45″W / 37.29778°N 78.39583°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Virginia |

| Counties | Prince Edward, Cumberland |

| Government | |

| • Type | Local |

| • Mayor | David Whitus |

| Area | |

| • Total | 7.3 sq mi (19.0 km2) |

| • Land | 7.2 sq mi (18.7 km2) |

| • Water | 0.1 sq mi (0.3 km2) |

| Elevation | 351 ft (107 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 8,216 |

| • Density | 1,140/sq mi (440.3/km2) |

| Time zone | Eastern (EST) (UTC-5) |

| • Summer (DST) | EDT (UTC-4) |

| ZIP codes | 23901, 23909, 23943 |

| Area code(s) | 434 |

| FIPS code | 51-27440[1] |

| GNIS feature ID | 1498477[2] |

| Website |

www |

Farmville is a town in Prince Edward and Cumberland counties in the U.S. state of Virginia. The population was 8,216 at the 2010 census.[3] It is the county seat of Prince Edward County.[4]

The Appomattox River traverses Farmville, along with the High Bridge Trail State Park, a more than 30-mile-long (48 km) rail trail park. At the intersection of US 15, VA 45 and US 460, Farmville is the home of Longwood University and is the town nearest to Hampden–Sydney College.

History

Near the headwaters of the Appomattox River, the town of Farmville was formed in 1798 and incorporated in 1912.

Upper Appomattox Navigation Canal System

Farmville was the end of the line for the Upper Appomattox Navigation canal system built between 1795 until 1850. African Americans built the canal system. Tobacco and farm produce could be loaded into a James River bateau in Farmville and sent to Petersburg, Virginia. The canals were used until railroads became common.[5] Many of the boatmen who worked in the Upper Appomattox canal near Farmville were free people of color, who lived in the Israel Hill community. Israel Hill was home to free African American laborers, craftsmen and farmers freed around 1810, and White people. People of African and European descent worked for the same wages; built a church together and could be defended in court within the 350 acre town.[6]

Local Coal

| Private | |

| Industry | Coal |

| Founded | (March 24, 1837) |

| Defunct |

1880's [7] |

| Headquarters | Farmville, Virginia |

Area served | Farmville |

| Website |

www |

John Flournoy was the first to mine coal near Farmville. He started in 1833 working on a seam, which was two feet thick. In 1837 the General Assembly granted a charter to “The Prince Edward Coal Mining Company” to mine and sell coal. This company was still in operation into the 1880s.[7]

Another coal pit in the 1880s was worked on the W.W. Jackson property. The coal from this small pit was used to fuel his blacksmith shop on the same property."[7] Farmville has coal deposits because it sits on the Farmville Basin, one of the Eastern North America Rift Basins west of modern day, Virginia State Route 45.[8]

Southside Railroad

In the 1850s, the Southside Railroad from Petersburg to Lynchburg was built through Farmville between Burkeville and Pamplin City. The route, which was subsidized by a contribution from Farmville, required an expensive crossing of the Appomattox River slightly downstream, which became known as the High Bridge.

Piedmont Mine

| Industry | Coal |

|---|---|

| Founded | 1860 in Raines Tavern, Virginia, Virginia, United States |

| Founder | John Dalby[8] |

| Website |

www |

The Virginia General Assembly chartered the Piedmont Coal Company for John Dalby in 1860. The mine was near Buckingham Plank Road, Virginia State Route 600 in Cumberland, a mile and a half west of Raines Tavern, Virginia.

Without rail transportation close to Raines Tavern, the transportation cost of getting the coal to Farmville and then by rail to Richmond was to high to sell it at a competitive price. The coal was sold locally to people in the area for heating their homes.

During the American Civil War, the mines continued to operate but then production fell off. Coal was still there, though, Daddow and Bannon documented seven or eight coal seams and anthracite in 1866.[8]

Civil War

Photo by Timothy H. O'Sullivan, 1865

Robert E. Lee retreated through Farmville as he escaped the Union Army in the Civil War. Farmville was the object of the Confederate Army's desperate push to get rations to feed its soldiers near the end of the American Civil War. The rations had originally been destined for Danville, but an alert quartermaster ordered the train back to Farmville. Despite an advance of the cavalry commanded by Fitzhugh Lee, the Confederate Army was checked by the arrival of Union cavalry commanded by Gen. Philip Sheridan and two divisions of infantry. General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia found itself soon surrounded. He surrendered at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865.

The Prince Edward county seat was moved from Worsham to Farmville in 1871.

Clay Brick Kiln

There was a brick making industry, in Farmville, using the clay of the Farmville Basin. In 1874, M.R. Murkland built a kiln for his hand-formed bricks. He made around 600,000 bricks each year.[7] The Triassic Clay of the Farmville Basin was mixable and plastic enough and would not shrink too much which made it suitable for bricks.[8]

Rail Transport

Rail Transport from Cumberland County helped Cumberland farmers sell fruits, vegetables and timber to Farmville markets.[10][11] From 1884 to 1917, the Farmville and Powhatan Railroad, later named the Tidewater and Western Railroad, was important to Cumberland County residents for markets and transportation and the telegraph. The owners hoped that the line could ship products all the way to the end of the line in Chester, Virginia and docks in the Tidewater region to make the railroad profitable. The line had trouble competing with the Standard gauge Southern railway.

Coal to Ship over Rails

| Private | |

| Industry | Coal |

| Founded | (1881) |

| Defunct | [7] |

| Headquarters | Farmville, Virginia |

Area served | Farmville |

| Website |

www |

It was rumored that the coal near Farmville would draw the Orange & Keysville Railway which was chartered, graded and the right of way was purchased, between Farmville and Hampden Sydney. The rails were never laid down, however. The coal field was idle until 1891 when the Farmville Coal and Iron Company began leasing land, selling stock and reopened the Piedmont mines. The company built a one and a half mile spur rail line from the Farmville and Powhatan Railroad to the mine. This railroad provided transport from the mine to the docks at Bermuda Hundred in the Tidewater region. On Jan. 24, 1891, an editor of “The Financial Mining Record” suggested that the The Farmville Coal & Iron Company, did not have enough coal production to justify a fraction of its stock price. The Norfolk and Western Railway, since 1883, had been bringing in coal from a new coal mine, the Pocahontas Coalfield which could provide coal more cheaply and ship the coal on a larger standard gauge, class one railroad. This decreased to the economic viability of mining coal in the Richmond and Farmville Basins.[12] The Farmville Coal and Iron Company went bankrupt a few years later, possibly before any coal was mined.

The Farmville Coal & Iron Company did bring positive change. They requested that the town build a electric power plant and a waterworks. Designation of the powerplant was established in 1890 and the water works were designated in 1893.[7]

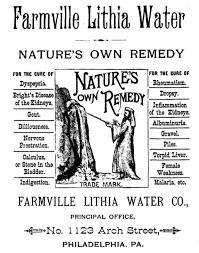

Farmville Lithia Springs

Farmville Lithia Springs Water Advertisement from Philadelphia | |

| Private | |

| Industry | Beverage |

| Fate | Bottling House burned down.[13] |

| Founded | (1884-08-24) |

| Defunct | 1901-07-07 (dissolved) |

| Headquarters | Farmville, Virginia |

Area served | International |

| Website |

www |

Farmville Lithia Springs bottled and sold mineral water from Farmville, Virginia from 1884 to 1901. The lithia springs were considered as a possible destination for tourists but the investors decided to bottle the water and ship it.[13] The water was tested and found to be superior to waters from Carlsbad, Germany. Lithia Springs Water from Farmville was shipped domestically and internationally for Water cure (therapy). The Springs were just north of the Appomattox River from Farmville, Virginia.

Lithia Springs water contained the following minerals naturally occurring in the water.

Proposed Projects in the last year of the Tidewater Western Railroad

In 1917 two attempts at stating industries which could have saved the Tidewater and Western Railroad, which had replaced the Farmville and Powhatan in 1905, by giving it something to haul.

Clay

Thomas A. Bolling tried brickmaking from clay in the Farmville Basin in 1917. He used a pug mill to make bricks from the clay. He had a plant on High Street. Ries and Somers tested his clay and clay from another pit and found that some of it could even be used for hollow bricks which must be stronger as well as drain tile.[15]

Oil

Also in 1917, the Tidewater Oil and Gas Company drilled a exploratory hole over 1500 feet deep in the Fork Swamp area in the Willis River. Oil was found about 1000 ft down but the company eventually closed 1921.[8]

Bankruptcy of the Tidewater Western Railroad

The Tidewater and Western, eventually could no longer make a profit. The line survived until 1917 when it was pulled up and sent to France for the World War I effort. The rails were never used for replacing bombed rails as had been planned.[16][17]

Automobile Roads built on Track Bed

The Tidewater and Western track bed in Cumberland County was replaced with Virginia State Route 13 in 1918, a road for automobiles. Virginia State Route 45, which was also built on the track bed of the Tidewater & Western Railroad, was built from Cumberland to Farmville in 1928.

Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County

Farmville and Prince Edward County Public Schools were the source of Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County (1952–54), a case incorporated into Brown v. Board of Education (1954), the landmark case that overturned school segregation in the United States. Among the cases consolidated into the Brown decision, the Davis case was the only one involving student protests.

R.R. Moton High School, an all-black school in Farmville named for Robert Russa Moton, suffered from terrible conditions due to underfunding by white officials in the segregated state. The school did not have a gymnasium, cafeteria, or teachers' restrooms. Teachers and students did not have desks or blackboards, and due to overcrowding, some students had to take classes in a school bus parked outside. The school's requests for additional funds were denied by the all-white school board. Students had protested against the poor conditions.

As a result of the Brown decision, in 1959 the Board of Supervisors for Prince Edward County refused to appropriate any funds for the County School Board; in massive resistance, it effectively closed all public schools rather than integrate them. Wealthy white students usually attended all-white private schools called segregation academies that formed in response. Black and poorer white students had to go to school elsewhere or forgo their education altogether. Prince Edward County's public schools remained closed for ten years. When they finally reopened, the system was fully integrated.

Prince Edward Academy was the longest-surviving of the segregation academies, still teaching students in the 1990s. Although technically integrated at that point, the school had few students of color. Prince Edward Academy was renamed the Fuqua School in honor of J.B. Fuqua, a wealthy businessman who was raised nearby and who has endowed the school.

The former R.R. Moton High School building has been recognized as a community landmark. In 1998, it was designated as a National Historic Landmark for its significance to the Civil Rights Movement. It houses the Robert Russa Moton Museum, a center for the study of civil rights in education.[18] In 2015, Longwood University and Moton Museum entered into a formal affiliation to advance understanding of the history of the struggle for civil rights.

National Register of Historic Places

The First Baptist Church, Farmville Historic District, Longwood House, Robert Russa Moton High School, Sayler's Creek Battlefield, and Worsham High School are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[19][20]

Today

Farmville is a growing community mainly because of economic growth in the Lynchburg and Richmond areas; many residents use Farmville as a bedroom community to take advantage of the low cost of living. Many Longwood alumni are staying in the community after growing up elsewhere.

Farmville made headlines in September 2015 after being selected by the Commission on Presidential Debates to host the 2016 vice-presidential debate. The debate was held at Longwood University on October 4, 2016.[21][22]

In 2008 a new YMCA was opened behind the recently built Lowe's. It includes an indoor swimming pool, locker rooms, six large HD TVs overlooking a gym, a child care center, and athletic fields. Family locker rooms, a teen center and aerobics room are included.

The town is crossed by the High Bridge Trail State Park which extends 4 miles (6 km) east to the historic High Bridge.

Geography

Farmville is located in northern Prince Edward County, with the town center situated south of the Appomattox River. A portion of the town extends north across the river into Cumberland County.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the town covers a total area of 7.3 square miles (19.0 km2), of which 7.2 square miles (18.7 km2) is land and 0.12 square miles (0.3 km2), or 1.77%, is water.[3]

Farmville is located between Petersburg and Lynchburg on U.S. Route 460. Petersburg is 67 miles (108 km) to the east, and Lynchburg is 48 miles (77 km) to the west.

Climate

The climate in this area is characterized by hot, humid summers and generally mild to cool winters. According to the Köppen Climate Classification system, Farmville has a humid subtropical climate, abbreviated "Cfa" on climate maps.[23]

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1860 | 1,536 | — | |

| 1870 | 1,543 | 0.5% | |

| 1880 | 2,058 | 33.4% | |

| 1890 | 2,404 | 16.8% | |

| 1900 | 2,471 | 2.8% | |

| 1910 | 2,971 | 20.2% | |

| 1920 | 2,586 | −13.0% | |

| 1930 | 3,133 | 21.2% | |

| 1940 | 3,475 | 10.9% | |

| 1950 | 4,375 | 25.9% | |

| 1960 | 4,293 | −1.9% | |

| 1970 | 4,331 | 0.9% | |

| 1980 | 6,067 | 40.1% | |

| 1990 | 6,046 | −0.3% | |

| 2000 | 6,845 | 13.2% | |

| 2010 | 8,216 | 20.0% | |

| Est. 2015 | 8,169 | [24] | −0.6% |

As of the census[1] of 2010, there were 8,216 people, 2,634 households, and 1,162 families residing in the town. The population density was 1,140.3 people per square mile (x379.2/km²). There were 2,885 housing units at an average density of x329.3 per square mile (x127.1/km²). The racial makeup of the town was 72.3% White, 23.8% African American, 0.4% Native American, 1.2% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 0.6% from other races, and 1.5% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 2.3% of the population.

There were 2,634 households out of which 19.7% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 26.0% were husband-wife couples living together, 3.5% had a male householder with no wife present, 14.6% had a female householder with no husband present, and 55.9% were non-families. 49.2% of all households were made up of individuals and 26.9% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.18 and the average family size was 2.90.

The age distribution, strongly influenced by the presence of Longwood University, is: 12.9% under the age of 18, 46.1% from 18 to 24, 14.9% from 25 to 44, 14.1% from 45 to 64, and 11.9% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 22 years. For every 100 females there were 68.9 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 64.9 males.

The median income for a household in the town was $26,343, and the median income for a family was $33,000. Males had a median income of $30,974 versus $20,764 for females. The per capita income for the town was $13,552. About 19.9% of families and 22.0% of the population were below the poverty line, including 25.8% of those under age 18 and 11.7% of those age 65 or over.

Arts and culture

Heart of Virginia Festival

The Heart of Virginia Festival happens in Farmville the first weekend in May and has grown every year since it was established in 1978. "Heart of Virginia" refers to Farmville's location in the central part of the state. (The actual geographic center of the state is 20 miles (32 km) north at the intersection of Route 24 and 60 outside of Dillwyn in Buckingham County). The festival includes all the traditional fare and concludes with a fireworks show at the Farmville airport.

First Fridays

First Fridays, held on the first Friday of every month from May to September, features bands and family events at Riverside Park.

Government

Services include the Farmville Police Department, Prince Edward County Sheriff's Office, and Longwood University Police Department. The Virginia State Police also has a strong presence in the town of Farmville. Piedmont Regional Jail, serving a six-county area, is located in Farmville.

Education

Longwood University is a public school located in the heart of town with an enrollment of about 5,000. It is one of the oldest public institutions in the country, founded as a female seminary. Longwood is mainly known as a teachers school and was once called State Female Normal School. This school is known as the mother of sororities: Sigma Sigma Sigma, Alpha Sigma Alpha, Zeta Tau Alpha, and Kappa Delta were founded here. Longwood University opened a new recreational complex, and in 2007 finished construction on a 36,000-square-foot (3,300 m2), four-story multi-use complex, with retail stores on the lower floor with dorms above. It is steadily expanding as a university.

Hampden–Sydney College is the 10th oldest college in America, an all-male private school founded in 1775. Hampden–Sydney is located 6 miles (10 km) southwest of the center of Farmville and has an enrollment of 1,200 students.

Infrastructure

Volunteer fire fighting

The Farmville Volunteer Fire Department is designated as Company 1[26] in Prince Edward County after being the first fire department established in the county in 1870. FFD provides services to nearly 10,000 people in their first due,[27] which comprises the entire town of Farmville, and into the immediately surrounding area of Prince Edward County, Buckingham County, and Cumberland County.

Firefighting apparatus include 1250-, 1000-, 750- and 270-gallon engine/pump trucks, chief-use SUV, and a support pick-up truck, along with a hazmat, decontamination, and spill/leak supply trailer.

Water

Farmville's water and sewer services are publicly owned and operated by the Town of Farmville work crew.[28] The town's water treatment plant draws its water supplies from the Appomattox River. Water from the river is treated to kill any waterborne pathogens. After that process all sedimentation is removed through a series of filtration tanks. The water plant sells a portion of this removed sedimentation to be mixed with topsoil and then to be made ready for farm use. The excess sedimentation is recycled back into the Appomattox. The water plant can store 200,000 gallons of fresh water which can be transferred to Farmville's water towers when needed. Currently Farmville averages 1 million gallons of water usage per day, and its water plant is capable of producing up to 3 million gallons. The water is used by the majority of the town and the Prince Edward schools.[29]

The town of Farmville is located within the Piedmont Region and has many tributaries which filter into the Appomattox River. After the water reaches the Appomattox River it drains into the James River and then is distributed into the Chesapeake Bay. Within Farmville there are several different areas which are a concern due to high amounts of heterotrophic bacteria and Escherichia coli, classified as coliform bacteria they live within the intestines of warm blooded animals. The strain of E. coli which is of most concern is the 0157 H7 strain because it can produce dehydration, vomiting, diarrhea, and in extreme cases even death. There are a couple of drains which are located within Farmville and its neighboring counties which are of concern, including Gross Creek, which usually exceeds the standards of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).[30]

The wastewater plant covers a more extensive area which includes all residents of Farmville, Prince Edward schools, Hampden Sydney and north to the Cumberland County Court area. The plant treats approximately 1.7 million gallons a day and is capable of handling 2.4 million gallons.[31] The wastewater undergoes an extensive treatment process based on parameters set by the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality[32] before being released back into the Appomattox River downstream of Farmville. All residents of Farmville are required to use the public sewage line. The only exception is granted to residents who have been using a private septic system prior to being annexed to the town. Both the water plant and the water treatment plant undergo a consumer confidence test every spring and have never received any violations. Contamination levels in the town's waterways are currently being checked bimonthly to monitor the water quality of creeks and streams leaving Farmville. Tests are conducted to see if the town's water pipes are leaching any pollutants into the environment and to detect any other sources of contamination. The information from test results is available at the Virginia DEQ website.[33]

Notable people

- Chris Ashworth, actor

- Lieutenant General William G. Boykin, former United States Deputy Undersecretary of Defense

- J. B. Fuqua (pronounced "few–kwah") (June 16, 1918–April 5, 2006), businessman, philanthropist and chairman of The Fuqua Companies and Fuqua Enterprises, born 10 miles (16 km) west in Prospect; he resided the majority of his life in Atlanta

- Vince Gilligan, writer for The X-Files and creator and writer of Breaking Bad

- James B. Hughes, publisher, abolitionist, congressman

- Joseph E. Johnston, Confederate general

- The Lady of Rage, (born 1968) American female rapper/recording artist

- Major Walter Reed, M.D., U.S. Army physician

- Angus Wall, editor

- Randall J. Webb, educator; taught mathematics at Longwood University, 1966 to 1974; later president of Northwestern State University in his native Natchitoches, Louisiana

- James Edward Maceo West, co-inventor of the electret microphone

- Lieutenant General Samuel V. Wilson, former Director of the Defense Intelligence Agency and President Emeritus of Hampden–Sydney College; credited for helping to create Delta Force

- Dorothy Johnson Vaughan, mathematician

Longwood University students

- Jerome Kersey (2006), basketball player (drafted in the second round in 1984 by the Portland Trail Blazers, but did not finish degree until 2006)

- Pat McGee, lead singer of the Pat McGee Band

- Jason Mraz, singer-songwriter

- Michael Tucker (1993), baseball player

References

- 1 2 "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- 1 2 "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Farmville town, Virginia". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Retrieved August 26, 2015.

- ↑ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- ↑ "UPPER APPOMATTOX CANAL". Virginia is for Lovers. VIRGINIA TOURISM CORPORATION. 2016. Retrieved 2016-08-25.

- ↑ Jones, Randy (2009-04-15). "Ten New State Historical Highway Markers Approved" (PDF). Department of Historic Resources. Department of Historic Resources. Retrieved 2015-08-25.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Gaskins, Ray A. (2015-12-23). "Monthly Happenings in Farmville and Prince Edward County". The Farmville Herald. Farmville, Virginia. Retrieved 2016-08-04.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Wilkes and, Gerald P. (August 1882). GEOLOGY AND MINERAL RESOURCES OF THE FARMVILLE TRIASSIC BASIN, VIRGINIA (PDF) (Report) (Vol. 28 Num. 3 ed.). Charlottesville, Virginia: Virginia Division of Mineral Resources. Retrieved 2016-08-08.

- ↑ "Virginia Landmarks Register". Virginia Department of Historic Resources. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- ↑ Virginia. Dept. of Agriculture and Immigration; George Wellington Koiner (1909). A Handbook of Virginia. E. Waddey Company, printers. pp. 124–125.

- ↑ Norfolk and Western Railway Company. Agricultural and Industrial Dept (1916). Industrial and Shippers Guide. Union Print. and Manufacturing Company. pp. 22–23.

- ↑ Ann B. Miller (June 2011). ""Backsights" Essays in Virginia Transportation History Volume One: Reprints of Series One (1972-1985)" (PDF). Virginia DOT. Virginia Center for Transportation Innovation and Research. Retrieved April 26, 2016.

- 1 2 Covington, Edwina (September 2008). "Monthly Happenings in Farmville and Prince Edward County". Farmville-Prince Edward Historical Society. Southside Virginia Historical Press. Retrieved 2016-08-01.

- ↑ A History of Prince Edward County, Virginia, from Its Formation in 1753, to the Present. Williams printing Company. 1922. pp. 47–48.

- ↑ RIES, H. R.; SOMERS, E. (1917). The Clays Of the Piedmont Province,Virginia (VIRGINIA GEOLOGICAL SURVEY) (Report) (Bulletin NO . XIII ed.). Charlottesville, Virginia: UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA. pp. 22–26. Retrieved 2016-08-04.

- ↑ George Woodman Hilton (1990). American Narrow Gauge Railroads. Stanford University Press. pp. 543–. ISBN 978-0-8047-1731-1.

- ↑ The Southeastern Reporter. West Publishing Company. 1903. pp. 555–.

- ↑ , Moton Museum official website Archived May 9, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ National Park Service (2010-07-09). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- ↑ "National Register of Historic Places Listings". Weekly List of Actions Taken on Properties: 2/25/13 through 3/01/13. National Park Service. 2013-03-08.

- ↑ "Longwood University to host 2016 Vice-Presidential Debate". WTVR.com.

- ↑ "2016 Vice Presidential Debate at Longwood". 2016 Debate at Longwood.

- ↑ "Farmville, Virginia Köppen Climate Classification (Weatherbase)". Weatherbase.

- ↑ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015". Retrieved July 2, 2016.

- ↑ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ↑ Prince Edward Fire & Ems Agencies

- ↑ Farmville Fire Department Inc. "Farmville Fire Department Inc.".

- ↑ "Welcome to the Town of Farmville". March 5, 2010.

- ↑ Stutler, Tim. water treatment operator. Personal INTERVIEW. 12 February 2010

- ↑ http://www.epa.gov/lawsregs/laws/cwa.html. Web.

- ↑ Meador, Sandy. Superintendent at Farmville waste water treatment plant. Personal INTERVIEW. 12 February 2010

- ↑ "Wastewater Treatment". Virginia DEQ. March 5, 2010.

- ↑ "Monitoring Sites". Virginia DEQ. March 14, 2010.