Fort Eustis Military Railroad

| |

Fort Eustis's GP16 diesel locomotive outside Gray Rail Shops. | |

| Locale | Fort Eustis Military Base |

|---|---|

| Dates of operation | 1950s–Present |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge |

| Length | 31 mi (50 km) |

| Headquarters | Newport News, Virginia |

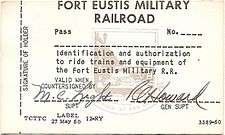

The Fort Eustis Military Railroad is an intra-plant United States Army rail transportation system existing entirely within the post boundaries of the United States Army Transportation Center and Fort Eustis (USATCFE), Fort Eustis, Virginia. It has served to provide railroad operation and maintenance training to the US Army and to carry out selected material movement missions both within the post and in interchange with the US national railroad system via a junction at Lee Hall, Virginia. It consists of 31 miles (50 km) of track broken into three subdivisions with numerous sidings, spurs, stations and facilities.

This article concentrates on the height of US Army rail operations on the Fort Eustis Military Railroad from the late 1950s to the mid-1960s prior to divestiture of the rail operations and maintenance missions in the 1970s when they were turned over to civil servants and later to contractors, and the rail training mission transferred to the 84th Training Command. The Utility Rail Branch (URB) of the Fort Eustis Military Railway continues to operate today under the command of the 733RD Logistics Readiness Division (LRD), Joint-Base Langley Eustis. The Utility Rail Branch of the Fort Eustis Military Railroad joined Operation Lifesaver in 2010.

Physical layout

The general layout of the Fort Eustis Military Railroad (FEMRR) is that of a loop within a loop, with a long track leading to the junction with the CSX (former Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad) line at Lee Hall. The smaller, inner loop is the Mulberry Island Subdivision, the larger, outer loop is the James River Subdivision, and the track to the Lee Hall Junction with CSX is the Industrial Subdivision. There are several spurs and one large branch, the Port Branch off the Industrial Subdivision, leading to the “Third Port” area of the post on the James River where the Army operates amphibious ships, landing craft and lighters. There are two wyes for turning equipment or whole trains: one at King Junction between the Mulberry Island and James River Subdivisions, and the other at the junction of the Industrial Subdivision with the Mulberry Island and James River Subdivisions. This latter wye was for years the site of a prominent Wye Tower that has since been removed, though the wye itself remains. The wye at King Junction served more as crossovers than as a wye; the turning of equipment and trains was normally performed at the Wye Tower Interlocking Plant.

Running directions

Though the railroad is generally oriented roughly northeast-southwest, it is run as an east-west road, with westbound trains superior to eastbound trains of the same class. On the Industrial Subdivision, “west” is toward the wye and “east” is toward the Lee Hall Junction; on the Mulberry Island and James River Subdivisions, which are loops, “west” is counterclockwise and “east” is clockwise; on the Port Branch, “west” is toward Third Port and “east” is toward the junction with the Industrial Subdivision.

Turning of equipment

The circular nature of the Mulberry Island and James River subdivisions meant that the running of trains would concentrate flange wear on the outer wheels of cars and locomotives. To minimize excessive and uneven flange wear, all of the FEMRR rolling stock had to be turned through the wye each quarter. Every piece of rolling stock on the railroad had a red disc painted on one side, about 18 inches from the right end of the equipment as seen from that side. During the first two weeks of each calendar quarter, all rolling stock was moved through the wye to reverse the orientation of the equipment.

In the first and third quarters of each calendar year, equipment would be turned so that the red disc faced away from the Hanks Yard office; during the second and fourth quarters, equipment would again be turned so the red disc would be visible from that office. If normal train operations resulted in rolling stock oriented with its red disc facing the wrong way, it would have to be turned as soon as practicable to face the proper way for that quarter. Proper turning of equipment was the responsibility of the Hanks Yardmaster.

Operations, maintenance and training

From the end of the Korean War until June 1965, the FEMRR was operated by the 774th Transportation Group (Railway), which was composed of the 714th Transportation Battalion (Railway Operating) (Steam & Diesel Electric), which operated the line and maintained the track, and the 763rd Transportation Battalion (Railway Shop), which carried out maintenance of the locomotives, rolling stock and shop facilities. Both battalions trained active and reserve US Army soldiers, including National Guard and Army Reserve troops, on various aspects of railway operations and maintenance. On June 3, 1965, the Group and the Shop Battalion were deactivated, leaving the 714th TBROS&DE as the only active duty railway unit in the US Army.

In 1966-67 the FEMRR was operated by the 714th Transportation Battalion (Railway Operating) (Steam & Diesel Electric) which consisted of four subordinate units: Headquarters & Headquarters Company (the Battalion Commander was also titled "Division Superintendent," and the HQ Company Commander was titled "Commanding Officer and Chief Dispatcher"), Company A (Maintentance of Way) (commanded by the "Commanding Officer and Roadmaster"), Company B (Maintenance of Equipment (commanded by the "Commanding Officer and Master Mechanic") and Company C (Train Operating) (commanded by the "Commanding Officer and Trainmaster"). The compound titles were always used since the battalion was organized as a mirror of a civilian railroad division. There was no Railway Shop Battalion or Railway Group on active duty. Reserve railway units were hosted at Fort Eustis by the 714th for summer training.[1]

In April, 1967, the 663rd Transportation Company (Railway Car Repair) was activated to take over the car shop and rip track from Company B, 714th TBROS&DE. By 30 April, the company strength increased to five officers and 93 men but in the rush to expand suffered from a lack of personnel trained and experienced in operating the equipment. Most of the soldiers in the company were deployable. By 31 May, the company contained five officers and 142 enlisted men. By June, it began to function as a company but rapid turnover of personnel for overseas assignments created difficulties. The 157th Transportation Company (Boat) had been activated at Fort Story on 1 June 1966 then inactivated on 25 July 1966. It was later reactivated as the 157th Transportation Company (Diesel-Electric Locomotive Repair) at Fort Eustis on 1 August 1967 and spent the next year organizing.

On 25 January 1968, the 716th Transportation Group (Railway) was activated and initially received attachment of the 714th TBROS&DE with its attached 488th, 508th, and 663rd Transportation Companies. Later other companies were attached directly to the Group, but not a battalion headquarters. The 157th Transportation Company (Diesel-Electric Locomotive Repair) was not attached to the 714th TBROS&DE until 15 July 1968.

The 714th TBROS&DE, was finally inactivated on 22 June 1972. A much smaller unit, the 1st Railway Detachment, was activated in the wake of the inactivation of the 714th, with the mission of operating the post railway and training both active duty and reserve railroaders. The 1st Railway Detachment was inactivated on September 30, 1978.

Today, rail operations at Fort Eustis are carried out by Northrop Grumman Technical Services, Inc.[2] Rail training for military personnel is now conducted by instructors of the 8th Battalion, 84th Regiment, 4th Brigade of the 84th Training Command, who carry out “intensive resident training” at during periods at Fort Eustis, with oversight by civilian rail instructors at the school house.

Operating speeds

The small size of the railroad obviates the need for high running speeds, as do the short distances spanned. Operating speeds are therefore low as compared to longer railroads. The maximum speed for both passenger and freight trains on the “main line” of the Mulberry Island and James River Subdivisions therefore was 25 mph (40 km/h) with the maximum speed on the Industrial Subdivision being 15 mph (24 km/h). On all subdivisions, the maximum speed through sidings, within yard limits, on spurs and through switches was also 15 mph (24 km/h). There were more restrictive maximum speeds specified for dead engines (engines not under power while being towed), which were 15 mph (24 km/h), rail mounted derricks and cranes run between 5 mph (8.0 km/h) and 10 mph (16 km/h), and track motor cars travel to about 2 mph (3.2 km/h) and 15 mph (24 km/h).

Fire prevention

Wildfires were a constant consideration during the dry and hot seasons at Fort Eustis, and special care had to be taken with ash pans and spark screens (spark arresters) on steam locomotives and with carbon deposits breaking loose and flying from diesel-electric locomotives. Train crews were cautioned to be alert to defects or operating conditions that could lead to the setting of fires and to take corrective or ameliorating action to remove or minimize the chances of setting a trackside fire.

For the same reason, combustible rubbish would not be allowed to accumulate on railroad property. During wet, rainy weather when there was no danger of setting fires, the diesel locomotives were to be assigned heavier “tonnage” trains so the additional horsepower requirements would allow the clearing of carbon deposits. Such was the degree of the carbon spark problem that the 714th TBROS&DE had to monitor it and make tonnage assignments as necessary and practicable to keep it under control. In fact, the operations sergeant (“S-3”) of the 714th TBROS&DE stated that the fire hazard from the diesel carbon sparks was significantly greater than that from the steam locomotive ash.

In addition, steam locomotives were not to enter the east end of the Steam Shop at Hanks Yard or be used to switch the 763rd TB(RS) rip track because of the fire hazard posed by the diesel refueling point nearby. A similar hazard existed at Patton on the Mulberry Island Subdivision due to the proximity of gasoline tanks at the east switch; engines were to be allowed to “drift” past this location whenever possible to minimize the chances of ejecting sparks or ash.

The Commanding Officer, Company A, 714th TBROS&DE formulated and maintained a “Railroad Firefighting Plan” in case the Fort Eustis Fire Department needed assistance in combating a blaze on or near railroad property or in areas of the post accessible by rail. This plan encompassed the use of soldiers from both the 714th TBROS&DE and the 763rd TB(RS), common firefighting tools, tank cars filled with water, and any necessary locomotives with crews. Train crews were cautioned to be watchful for fires near the tracks or in the surrounding areas, extinguishing unattended fires if possible. If putting out the fire was not possible, the crews were instead to notify the Fort Eustis Fire Department; all fires were to be reported, regardless of whether or not the train crews could extinguish them first.

Interchange

The interchange of cars with the national rail system occurs only at the Lee Hall junction where interchange tracks exist linking the FEMRR to (originally) the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway (C&O) (now CSX). FEMRR engines and cars were not permitted on C&O tracks beyond the Yorktown Road grade crossing except in emergencies. Cars outbound from Fort Eustis would be spotted on a designated interchange track (other than passing track #493, which was a dedicated runaround track) and deemed delivered to the C&O when the bills of lading and switch lists were signed by the C&O station agent. Inbound cars would be spotted on the interchange track by the C&O and deemed delivered to the Government when uncoupled from the engine (or the rest of the train) that brought them there. FEMRR engines and trains were not allowed on the C&O main line except in emergencies. However, with proper prior arrangement, C&O trains or light engines (engines under power but not coupled to cars or dead engines) were allowed to operate on FEMRR tracks on the Industrial Subdivision (save the Port Branch), the Wye Tower Interlocking Plant, and the part of the James River Subdivision between O’Brien, the wye and Hanks, including Hanks Yard. The Commanding Officer, Company A, 714th TBROS&DE had to approve the use of any other tracks by the C&O. All C&O trains and light engines were to be provided a pilot and any necessary highway crossing protection.

Equipment

For what was essentially an industrial railroad, the FEMRR had an extensive equipment roster. At its height in the late 1950s through the mid-1960s, the FEMRR listed eight steam locomotives, nine diesel-electric locomotives, and 162 coaches and freight cars, including “non-revenue” cars. This list did not, however, include equipment assigned to the Transportation Research and Engineering Command (TRECOM), the Transportation School (“T School”) or Depot Storage. Some of the equipment used over the years and listed here is in the collection of the U.S. Army Transportation Museum at Fort Eustis, though only a small portion is on public display.

Locomotives

As might be expected of a flat industrial railroad, almost half (8) of the 17 FEMRR engines were switch engines, with the remaining locomotives low-horsepower road-switchers and small steam locomotives not larger than Consolidations. Currently, the Army at Fort Eustis has only three active locomotives: two 120-ton diesels (No. 1880, a GP10, and No. 4635, a GP16, both second-hand road switchers) used to train students at the Transportation School and a GE 80-ton diesel (No. 1663) used at the T-school shop.[3]

Steam locomotives

Of the eight steam locomotives on the FEMRR at its height, two were 0-6-0 switchers and the rest 2-8-0 road engines.

- 0-6-0

- Nos. 613 an 617, Alco switchers built 1942

- 2-8-0

- Nos. 606 and 607, Lima, built 1945; No. 607 is preserved at the Transportation Museum

- No. 610, Baldwin-Lima-Hamilton (BLH) built 1952; No. 610 is preserved at the Tennessee Valley Railroad Museum

- Nos. 611 and 612, Baldwin, built 1943 (No. 611 rebuilt by BLH in 1949)

- No. 620, Alco, built 1942

By 1966-67, the steam roster had declined to two operating 2-8-0s (610 & 620), with one additional 2-8-0 as a non-operating static display and training aid. All of the 0-6-0s had been scrapped or given to museums.

Diesel-electric locomotives

The FEMRR operated up to nine diesel-electric locomotives built between 1944 and 1954. The 1958 roster shown below is probably representative of FEMRR motive power through the mid-1960s, though a few newer locomotives replaced some older ones listed here, particularly as steam was phased out.

Of particular interest to many observers were the Military Road Switchers designated MRS-1 and built specifically for the US Army Transportation Corps. These engines were constructed by the Electromotive Division of General Motors and by the American Locomotive Company (Alco) with trucks that could adjust to accommodate selected track gauges between 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge and broader gauges up to 5 ft 6 in (1,676 mm). The reason for this was the potential use of these locomotives on the railroad networks of Europe and the USSR where broader gauges precluded the use of unmodified US locomotives in the event of a major war. While built to the same specifications, there were external differences between the EMD and Alco MRS-1s as can be seen in the rooflines.

- B-B or 0-4-4-0

- C-C or 0-6-6-0

- No. 1812, EMD MRS-1 1,600 hp (1,200 kW) built 1952

- No. 1813, EMD MRS-1 1,600 hp (1,200 kW) built 1952

- No. 1819, EMD MRS-1 1,600 hp (1,200 kW) built 1952

- No. 1820, EMD MRS-1 1,600 hp (1,200 kW) built 1952

- No. B2043, Alco MRS-1 1600 hp built 1953

- No. B2047, Alco MRS-1 1600 hp built 1953

- No. B2074, Alco MRS-1 1600 hp built 1953

- No. 8651, Alco 1,000 hp (750 kW) built 1945

- No. 8674, Alco 1,000 hp (750 kW) built 1945

Rolling stock

For a small railroad, the FEMRR rostered a surprising extensive collection of passenger, freight, maintenance-of-way and other cars, totaling 168 pieces. Most of these were equipped with traditional AAR knuckle couplers, but a number were outfitted with European link-type buffers and chain couplers at one or both ends in case they were needed overseas. Adapter cars had AAR couplers on one end and link-type couplers at the other end, whereas foreign service cars had link-type couplers at both ends. The cars listed below are from the 1958 timetable and probably constitute the maximum equipment roster of the FEMRR. Many of these cars, plus a few others that were added later as replacements for worn-out equipment, are still at Fort Eustis in varying states of repair, and several are in the collection of the Transportation Museum.

Freight cars

There were 117 freight cars listed by number in the 1958 timetable.

- Box cars: 27

- Flat cars: 38

- 30-ton: 5

- 40-ton: 24, including 2 adapter and 6 foreign service cars

- 50-ton: 5, including 2 adapter and 3 foreign service cars

- 80-short-ton (71.4-long-ton; 72.6 t): 4, including 2 foreign service cars

- Gondolas: 26

- 30-ton: 13, including 2 adapter cars

- 40-ton: 12, including 3 adapter and 6 foreign service cars

- 50 ton: 1

- Tank cars: 11

- Hopper cars: 5

- 50-ton: 5

- Dump cars: 10

- 30-ton (12-cubic-yard or 9.2-cubic-meter): 1

- 40-ton (20-cubic-yard or 15-cubic-meter): 5

- 50-ton (30-cubic-yard or 23-cubic-meter): 4

Passenger Equipment

A total of 30 passenger cars, mostly coaches, were on hand in 1958 and into the 1960s.

- Coaches: 18

- 58-seat: 1

- 60-seat: 6

- 64-seat: 1

- 70-seat: 5

- 75-seat: 2

- 80-seat: 3

- Sleeper cars: 5

- Diner cars: 3

- Kitchen cars: 2

- Shower cars: 2

Miscellaneous cars

Maintenance-of-way and other non-revenue-type cars totaled 21 pieces.

- Cabooses: 3; No. 995 is preserved at the Transportation Museum

- Tool cars: 1

- Power cars: 1

- Shop cars: 1

- Wrecker idler cars (gondolas): 1

- Wrecker tenders: 1

- Camp box cars: 7

- Cranes: 5

- 7.5-short-ton (6.7-long-ton; 6.8 t), Burro: 2

- 25-short-ton (22.3-long-ton; 22.7 t), Orton: 1

- 75-short-ton (67.0-long-ton; 68.0 t), Orton: 1

- 75-ton, IBH : 1, preserved at the Transportation Museum

- Spreaders: 1

- Jordan spreader: 1, preserved at the Transportation Museum

Preservation

Some of the older railway equipment is preserved at the US Army Transportation Museum, located on the Industrial Subdivision. This museum is open to the public and contains a wide variety of military transportation equipment and displays, including some railroad equipment and interpretive exhibits. However, most of the museum is dedicated to non-rail transportation systems.

EMD MRS-1 USA 1820 has been restored by the Pacific Southwest Railway Museum in Campo, California, where it operates pulling excursion trains. (Another EMD MRS-1, USA 1809, which did not operate on the FEMRR, is also at Campo.) USA 1811 has been restored and placed in the US Army Transportation Museum. USA 1813, which was present at Fort Eustis in the 1970s, is now on the Heber Valley Railroad, an excursion line in Utah. Ex-USA 606, an S160 steam locomotive, is on display with Norfolk & Western Railway markings at the Crewe Railroad Museum in Crewe, Virginia.[4] Steam locomotive USA 610 was restored by the Tennessee Valley Railroad Museum in 1990 and now operates excursion trains in Southeastern Tennessee and Northwestern Georgia. The Tennessee Valley Railroad Museum also has possession of USA 611, to be restored to operating condition in the future.

Some of the freight cars rostered in the 1960s still exist at Fort Eustis, although most of the old cars have been sold for their scrap value via the Defense Reutilization Marketing Office (DRMO). Newer rolling stock used for deployments and other shipping may be seen on the post, to include Army box cars and flat cars.

Gallery

-

Fort Eustis's GP16 diesel locomotive sits silently under the Post flag which is at half mast for former President Gerald Ford who died that day.

-

USAX 1663 a GE 80-ton switcher at Fort Eustis.

-

GE 80-Ton moving cars at the Fort Eustis Railhead operated by Utility Rail.

See also

References

- The Fort Eustis Military Railroad Timetable No. 7. 1958. p. 60.

- From the personal papers of CPT G. D. Clark, Jr., CO & Master Mechanic, Co B, 714th TBTOS&DE

External links

- US Army Transportation Center and Fort Eustis

- US Army Transportation Museum

- Pacific Southwest Railroad Museum

Coordinates: 37°09′25″N 76°35′49″W / 37.1569°N 76.597°W