Free Imperial City of Nuremberg

| Free Imperial City of Nuremberg | ||||||||||

| Freie Reichstadt Nürnberg (German) | ||||||||||

| Free Imperial City of the Holy Roman Empire | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

Nuremberg, shown within the Holy Roman Empire as at 1648 | ||||||||||

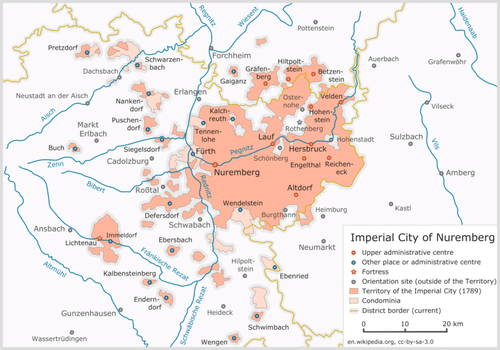

Territory of the Imperial City, with modern district borders in yellow. City lands in darker pink, condominiums in paler pink. | ||||||||||

| Capital | Nuremberg | |||||||||

| Government | Republic | |||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | |||||||||

| • | First documentary mention |

1050 | ||||||||

| • | Großen Freiheitsbrief | 1219 | ||||||||

| • | Burgraviate sold to city, exc. Blutgericht |

1427 | ||||||||

| • | Golden Bull | 1356 | ||||||||

| • | Landshut War of Succession |

1503–05 | ||||||||

| • | Reformation | 1525 | ||||||||

| • | Annexed by Bavaria | 1806 | ||||||||

| ||||||||||

| Today part of | | |||||||||

The Imperial City of Nuremberg (German: Reichsstadt Nürnberg) was a free imperial city — independent city-state — within the Holy Roman Empire. After Nuremberg gained piecemeal independence from the Burgraviate of Nuremberg in the High Middle Ages and considerable territory from Bavaria in the Landshut War of Succession, it grew to become one of the largest and most important Imperial cities, the 'unofficial capital' of the Empire, particularly because Imperial Diets (Reichstage) and courts met at Nuremberg Castle. The Diets of Nuremberg were an important part of the administrative structure of the Empire. The Golden Bull of 1356, issued by Emperor Charles IV (reigned 1346–78), named Nuremberg as the city where newly elected kings of Germany must hold their first Imperial Diet, making Nuremberg one of the three highest cities of the Empire.[1]

The cultural flowering of Nuremberg, in the 15th and 16th centuries, made it the center of the German Renaissance. Increased trade routes elsewhere and the ravages of the major European wars of the 17th and 18th centuries caused the city to decline and incur sizeable debts, resulting in the city's absorption into the new Kingdom of Bavaria on the signing of the Confederation of the Rhine in 1806, becoming one of the many territorial casualties of the Napoleonic Wars in a period known as the German mediatisation.

Middle Ages

(from the Nuremberg Chronicle).

First evidence of a settlement in the Nuremberg area can be detected as early as the year 1050 BC. Later the Celts settled in the Nuremberg area, c. 400 BC. The area of the city of Nuremberg itself — and especially today's old town — has detectable traces of a settlement as early as the 9th century.[2] At that time, present-day Nuremberg was on the border between the Bavarian Nordgau and the stem duchy of Franconia. Nuremberg was probably founded around the turn of the 11th century, according to the first documentary mention of the city in 1050, as the location of an Imperial castle between the East Franks and the Bavarian March of the Nordgau.[1] From 1050 to 1571, the city expanded and rose dramatically in importance due to its location on key trade routes.

King Conrad III established a burgraviate and the first administration and courts over the surrounding Imperial territories. The first burgraves were from the Austrian House of Raab but, with the extinction of their male line around 1190, the burgraviate was inherited by the last count's son-in-law, of the House of Hohenzollern. From the late 12th century to the Interregnum (1254–73), however, the power of the burgraves diminished as the Staufen emperors transferred most non-military powers to a castellan, with the city administration and the municipal courts handed over to an Imperial mayor (German: Reichsschultheiß) from 1173/74.[1][3] This castellan not only administered the imperial lands surrounding Nuremberg, but levied taxes and constituted the highest judicial court in matters relating to poaching and forestry; he also was the appointed protector of the various ecclesiastical establishments, churches and monasteries, even of the Prince-Bishopric of Bamberg. The privileges of this castellanship were transferred to the city during the late-14th and early-15th centuries. The strained relations between the burgraves and the castellan finally broke out into open enmity, which greatly influenced the history of the city.[3]

Nuremberg is often referred to as having been the 'unofficial capital' of the Holy Roman Empire, particularly because Imperial Diets (Reichstage) and courts met at Nuremberg Castle The Diets of Nuremberg were an important part of the administrative structure of the empire. The increasing demands of the royal court and the increasing importance of the city attracted increased trade and commerce to Nuremberg, supported by the Hohenstaufen emperors. Frederick II (reigned 1212–50) granted the Großen Freiheitsbrief ("Great Letter of Freedom") in 1219, including town rights, Imperial immediacy (Reichsfreiheit), the privilege to mint coins, and an independent customs policy, almost wholly removing the city from the purview of the burgraves.[1][3] Nuremberg soon became, with Augsburg, one of the two great trade centers on the route from Italy to Northern Europe.

In 1298, the Jews of the town were accused of having desecrated the host and 698 were slain in one of the many Rintfleisch massacres. Behind the massacre in 1298 was also the desire to combine the northern and southern parts of the city, which were divided by the Pegnitz river. Jews had been settled in that flood-prone area, but as the city leaders realised, this center of town was crucial to its future development. Hence, they decided that the Jewish population had to be removed. This area is now the place of the city market, the Frauenkirche and the Rathaus.

The largest gains for Nuremberg were in the 14th century, with Louis the Bavarian (reigned 1314–47) and Charles IV (reigned 1346–78) expanding the city's powers and granting improved customs privileges. Charles's Golden Bull of 1356 named Nuremberg as the city where newly elected kings of Germany must hold their first Imperial Diet, making Nuremberg one of the three highest cities of the Empire, along with Frankfurt, where kings were elected, and Aachen, where Emperors were crowned and which had been the capital of the old Frankish Empire.[1] The royal and Imperial connection was strengthened when Sigismund of Luxembourg (reigned 1411–37) granted the Imperial regalia to be kept permanently in Nuremberg in 1423. These remained in Nuremberg until 1796, when the advance of French troops required their removal to Regensburg and thence to Vienna, where they found a new home.[1]

Charles IV had strong ties to Nuremberg, staying within its city walls 52 times and thereby strengthening its reputation amongst German cities. Charles was the patron of the Frauenkirche, built between 1352 and 1362 (the architect was likely Peter Parler), where the Imperial court worshipped during its stays in Nuremberg.

Until the mid-13th century, the Lesser, reigning, Council consisted of 13 magistrates and 13 councillors; towards the end of the century 8 members of the practically unimportant Great Council were added, and, from 1370, 8 representatives of artisans' associations.[3] The members of the council were chosen by the wealthier class; this custom led to the establishment of a circle of "eligibles", to which the artisan class was strongly opposed since it excluded them politically.[3] With the increasing importance of handicraft, a spirit of independence developed among the artisans, and they determined to have a voice in the city government. In 1349 the members of the guilds unsuccessfully rebelled against the patricians in the Handwerkeraufstand ("Craftsmen's Uprising"), supported by merchants and some councillors. This uprising was mainly political, with the agitators siding with the Wittelsbachs in the dispute over the German kingship between Louis's Bavarian heirs and the patricians, who sided with Emperor Charles. The result of this uprising was a ban on any self-organisation of the artisans in the city, abolishing the guilds that were customary elsewhere in Europe; the unions were then dissolved, and the oligarchs remained in power while Nuremberg was a free city.[1][3]

Charles IV conferred upon the city the right to conclude alliances independently, thereby placing it upon a politically equal footing with the princes of the empire.[3] The city protected itself from hostile attacks by a wall and successfully defended its extensive trade against the burgraves. Frequent fights took place with the burgraves without, however, inflicting lasting damage upon the city. After the castle had been destroyed by fire in 1420 during a feud between Frederick IV (since 1417 margrave of Brandenburg) and the duke of Bavaria-Ingolstadt, the ruins and the forest belonging to the castle were purchased by the city (1427), resulting in the city's total sovereignty within its borders; The castle had been ceded to the city by Emperor Sigismund in 1422, on the sole condition that the Imperial suite of rooms be reserved for the Emperor's use. Through these and other acquisitions the city accumulated considerable territory.[3]

In 1431, the population was about 22,800 including 7146 persons qualified to bear arms, 381 secular and regular priests, 744 Jews and non-citizens.[3] As an emerging regional power, however Nuremberg soon came into conflict with the old dynasty, the former burgraves, who had brought large areas of the region around the city under their control as the Margrave of Brandenburg-Kulmbach and Elector of Brandenburg. This conflict came to a head in the First Margrave War in 1449–50, when Albert III Achilles, Elector of Brandenburg, tried in vain to restore his former rights over the city. The Hussite Wars, recurrence of the Black Death in 1437 and the First Margrave War had reduced the city's population to 20,800 by 1450.[3]

Early modern age

The cultural flowering of Nuremberg, in the 15th and 16th centuries, made it the center of the German Renaissance. The years between 1470 and 1530 are generally regarded as the city's heyday. Nuremberg traded in virtually all of the then-known world: Nürnberger Tand geht durch alle Land ("Nuremberg trinkets go all through the land") and Nuremberg's wealth was known as "the Imperial Treasure Chest". The city's revenues were said to have been greater than those of the whole kingdom of Bohemia.[4] Nuremberg cities maintained trade offices in many cities, such as the Nürnberger Hof in Frankfurt. At that time, many notable artists lived and worked in Nuremberg, such as Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), Martin Behaim (1459–1507) built the first globe and Peter Henlein (c. 1485–1542) produced the first pocket watch. Also notable from this period are the woodcarver Veit Stoss (1447–1533), the sculptor Adam Kraft (c. 1460–1508/09) and the master founder and sculptor Peter Vischer the Elder (c. 1460–1529). Only literature was not as dominant as the other arts, but meistersinger (lyric poet), playwright and shoemaker Hans Sachs (1494–1576) provides at least one major literary figure who lived at this time in Nuremberg.

Nuremberg was one of the founding 27 territories of the Franconian Circle at the Diet of Augsburg on 2 July 1500. At the beginning of the 16th century, siding with Albert IV, Duke of Bavaria-Munich, in the Landshut War of Succession led the city to gain substantial territory, resulting in lands of 25 sq mi (65 km2), becoming the largest Imperial city in the Empire,[3] acquisitions confirmed by Maximilian I in 1505. In 1525, Nuremberg accepted the Protestant Reformation, and in 1532, the religious Peace of Nuremberg, by which the Lutherans gained important concessions, was signed there.[3] During the 1552 revolution against Charles V in the Second Margrave War, Nuremberg endeavoured to purchase its neutrality by the payment of 100,000 guilder; but Albert Alcibiades, Margrave of Brandenburg-Kulmbach, one of the leaders of the revolt, attacked the city without declaring war and forced the conclusion of a disadvantageous peace.[3] At the Peace of Augsburg, the possessions of the Protestants were confirmed by the Emperor, their religious privileges extended and their independence from the jurisdiction of the Bishop of Bamberg affirmed, while the 1520s' secularisation of the monasteries was also approved.[3]

The state of affairs in the early 16th century, Columbus's discovery of the New World and Dias's circumnavigation of Africa and the territorial fragmentation in the Empire led to a decline in trade and, thus, the city's affluence.[3] The ossification of the social hierarchy and legal structures contributed to the decline in trade; under Leopold I (reigned 1658–1705) the patriciate was converted to a hereditary corporation, leading the merchant class to appeal to the Imperial counsellor, albeit unsuccessfully.[1] During the Thirty Years' War it did not always succeed in preserving its policy of neutrality. Frequent quartering of Imperial, Swedish and League soldiers, war-contributions, demands for arms, semi-compulsory presents to commanders of the warring armies and the cessation of trade, caused irreparable damage to the city. The population, which in 1620 had been over 45,000, sank to 25,000.[3] In 1632 during the Thirty Years' War, the city, occupied by the forces of Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden, was besieged by the army of Imperial general Albrecht von Wallenstein. The city declined after the war and recovered its importance only in the 19th century, when it grew as an industrial center. Even after the Thirty Years' War, however, there was a late flowering of architecture and culture — secular Baroque architecture is exemplified in the layout of the civic gardens built outside the city walls, and in the Protestant city's rebuilding of the Egidienkirche, destroyed by fire at the beginning of the 18th century and considered a significant contribution to the baroque church architecture of Middle Franconia.[1]

After the Thirty Years' War, Nuremberg attempted to remain detached from external affairs, but contributions were demanded for the War of the Austrian Succession and the Seven Years' War, the former amounting to 6.5 million guilder.[3] Restrictions of imports and exports deprived the city of many markets for its manufactures, especially in Austria, Prussia and Bavaria, eastern and northern Europe.[3] In 1790/91, the Bavarian elector, Charles Theodore, appropriated part of the land obtained by the city during the Landshut War of succession, to which Bavaria had maintained its claim; Prussia claimed and occupied part of the territory in 1796.[3][5] Realising its weakness, the city asked to be incorporated into Prussia but Frederick William II refused, fearing to offend Austria, Russia and France.[3] At the Imperial diet in 1803, the independence of Nuremberg was affirmed, but on the signing of the Confederation of the Rhine on 12 July 1806, it was agreed to hand the city over to Bavaria from 8 September; its population was then 25,200 and its public debt totalled 12.5 million guilder, with Bavaria guaranteeing their amortisation.[3]

Territory

_Festung_Innenhof.jpg)

The Imperial City comprised some 1,200 square kilometres (460 sq mi), making it one of the largest imperial cities territories; after the Imperial City of Bern left to join the Old Swiss Confederacy in 1353, only the Imperial Cities of Ulm and Strasbourg had anything like the same amount of land.[5] The area was divided into the Old and New Districts (German: Alte Landschaft and Neue Landschaft). The Old District, which also included Imperial forests (German: Nürnberger Reichswald), was a conglomeration of lordships and possessions of Nuremberg burghers, monasteries and social facilities. That high justice (Zentgericht and Freisgericht) was administered by the burgraviate — and subsequently the margraviates of Brandenburg-Ansbach and Brandenburg-Bayreuth — was a source of constant conflict. The New District is made up of the territory gained by Nuremberg in the Landshut War of Succession; in this territory, the city had full sovereignty.[5] In 1790, around 25,000 lived with city walls and a further 35,000 in the extramural territories of the city.[5]

The territorial expansion of imperial cities since the mid-14th century had several general causes, all found in the case of Nuremberg — the weakness of imperial power and an inability to maintain law and order; the debt crisis of neighbouring landed and knightly nobles in comparison with the capital income of the burgeoning urban middle classes; and the growing need for cities to secure an adequate supply of food for its inhabitants, raw materials for its craftsmen, and military self-protection.[5] Before the end of the 18th century, with Bavarian and Prussian annexation of Nuremberger territory, the city territory was as described below:

Old District

The Old District was located mostly between the Grenzwässern ("border waters") of Erlanger Schwabach, Regnitz / Rednitz and Schwarzach. It included the suburbs of Gostenhof (since 1342 a burgravial fief of the Waldstromer family of Nuremberg, since 1477 a Nuremberg protectorate) and Wöhrd (part of the burgravial Amt of Veste, over which Nuremberg gained jurisdiction in 1427) as well as the Sebald and St Lorenz Imperial forests and the Knoblauchsland; the forests were territory directly belonging to the Empire (German: Reichsgut).[5] The fiefdom in the southern (St Lorenz) Imperial forest was jointly held by the Nuremberg families of Waldstromer (acquired by Nuremberg in 1396) and Koler (acquired in 1372); the northern (Sebald) forest, including the Knoblauchsland, was held by the burgraves and, thus, was acquired by Nuremberg in 1427 when it purchased the burgravial holdings, including the castle and, importantly, the right of high justice.[5] Whilst this was later disputed by the Hohenzollern margraves, the Reichskammergericht ("Imperial Chamber Court") confirmed these rights to Nuremberg in the Fraischprozess in 1583, though it remained a constant source of friction.[5]

Before 1790, Nuremberg held the Vogt and seigneurial rights for both woodland Ämter of Sebaldi and Laurenzi in the Old District, the Pflegamt of Gostenhof and the Amt of the fortress with the judicial office of Wöhrd. At the time, the high courts held jurisdiction over the Nuremberg farmers' courts, the forest courts of the two Imperial forests and the beekeepers' courts in Feucht.[5] Within but especially outside of the Old District, there were also exclaves (German: Straubesitz) that were indirect estates and possessions of Nuremberg citizens and of former religious institutions (such as the monasteries secularised by the city in the 16th century) and charitable institutions (in particular the Heilig-Geist-Spital). These territories extended geographically from the Steigerwald and Franconian Switzerland in the north to the region of Gunzenhausen and Greding in the south, from Ansbach in the west to the arc of the Franconian Jura in the east.[5] The Nürnberger Landalmosenamt ("Nuremberg rural alms Amt") alone — responsible, amongst other things, for the land of the former Nuremberger monasteries — managed around 1790 properties in over 500 locations. In 1497, excluding the exclaves, the Old District available to Nuremberg, there were over 28,000 people, living in 5780 households in 780 towns. These tenants owed to the Imperial city allegiance, obedience, military service and tax obligations.[5]

New District

In 1504/05, the New District comprised Pflegämtern in the following places, all now in Landkreis Nürnberger Land except where indicated:[5]

- Altdorf

- Betzenstein with Stierberg, now in Lkr Bayreuth

- Engelthal

- Hersbruck

- Hiltpoltstein, bought in 1503 now in Lkr Forchheim)

- Hohenstein and Wildenfels, bought in 1505 and 1511

- Lauf, Reicheneck and Velden

- Hauseck, now in Lkr Amberg-Sulzbach

- Pflegamt Gräfenberg (now in Lkr Forchheim) was successively acquired, in 1347 by Nuremberger families and in 1536 by the city itself

- Pflegamt Lichtenau, purchased in 1406, now in Lkr Ansbach

The structure of the Nuremberg Pflegämter resembles the administrative structure of the Electoral Palatinate and the duchies of Bavaria office structure prior to 1504.[5] In 1513, the Nuremberg Pflegämter were placed under the newly created Landpflegamt as an intermediate authority. In contrast to the Old District, the Pflegämter of the New District were demarcated with stones showing the limits of the city's judicial, financial and administrative powers exercised by the district.[5] Only in the Pflegämter of Altdorf and Lauf and extending into parts of the Imperial forests, did the margraviate deny high justice to the city authorities; the self-government of cities Altdorf (from 1575 including the University of Altdorf), Lauf, Hersbruck, Velden, Betzenstein and Gräfenberg remained under Nuremberger administration.[5]

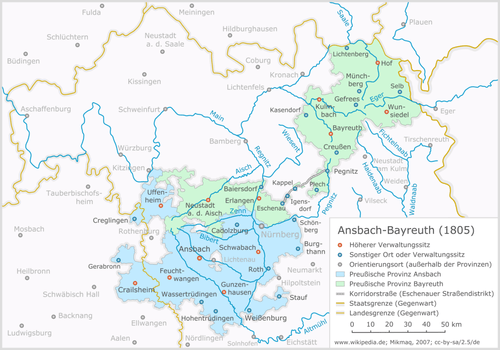

Gradual mediatisation from 1790

In both Margraves' Wars (1449/50 and 1552–54) and in the Thirty Years' War, the city's territory and its population were violently affected by quartering of troops, looting, troop movements and disease.[5]

After the ducal line of Bavaria fell extinct and the Electorate of Bavaria was inherited by Charles Theodore, Count Palatine of Sulzbach in 1777, the Electorate began to claim Nuremberg's exclaves in the Upper Palatinate as well as counting the Ämter of Heideck and Hilpoltstein into the County Palatine of Neuburg for judicial and tax purposes.[5] In 1790/91, the Electorate used its historic claim from before the Landshut War of Succession to occupy Nuremberger territories in what became known as the Bavarian Sequestrations (Bayerische Sequestrationen).[5]

Large parts of the Pflegämter Hiltpoltstein, Gräfenberg and Velden and were now occupied, which led to corresponding tax losses for Nuremberg; protests to the Emperor and the Empire were in vain, due to the military-political situation at the time.[5] The power-play over the Nuremberger legacy saw the Electorate providing goodwill and support to Revolutionary France in competition with Prussia, to whom the two Franconian margraviates had fallen in 1791.[5] Since then, the Minister President of Prussia, Karl August von Hardenberg (1750–1822), had been trying to create an integral Prussian Province of Franconia. When Prussia, in the course of her Revindikationspolitik, had already claimed the margravial rights of high justice (Fraischbezirk) over the Old District in 1796, Nuremberg was all but restricted to the territory circumscribed by town walls; Nuremberg retained the right of high justice only over the reduced Pflegamt Lichtenau and the exclaves within the Prince-Bishopric of Bamberg, also diminished by annexation by the Electorate.[5]

In 1972, most of the former territories of Nuremberg — particularly those in the New District — were reunited into the Bavarian Landkreis of Nürnberger Land.[5]

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nürnberg. |

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Nürnberg, Reichsstadt: Politische und soziale Entwicklung" [Political and Social Development of the Imperial City of Nuremberg]. Historisches Lexikon Bayerns (in German).

- ↑ Hartmut Voigt (11 March 2015). "Sensationsfund: Nürnberg 100 Jahre älter als gedacht" [Sensational discovery: Nuremberg 100 years older than thought]. NordBayern.de. Nürnberger Nachrichten and Nürnberger Zeitung. Retrieved 21 May 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Nuremberg". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Nuremberg". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. - ↑ Friedrich Nicolai. Einige Nachrichten von Nürnberg. Berlinische Monatsschrift 1/1783 (in German). p. 89., referenced in History of the City of Nuremberg on the German Wikipedia.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 "Nürnberg, Reichsstadt: Territorium" [Territory of the Imperial City of Nuremberg]. Historisches Lexikon Bayerns (in German).

Sources

- Sigmund Benker; Andreas Kraus, eds. (1997). Geschichte Frankens bis zum Ausgang des 18. Jahrhunderts [The history of Franconia to the end of the 18th century] (in German) (3rd ed.). Munich: Beck. ISBN 3-406-39451-5.

- Max Spindler; Gertrud Diepolder (1969). Bayerischer Geschichtsatlas [Atlas of Bavarian History] (in German). Munich: Bayerischer Schulbuch-Verlag.

- Gerhard Taddey (1998). Lexikon der deutschen Geschichte [Lexicon of German History] (in German) (3rd ed.). Stuttgart: Kröner. ISBN 3-520-81303-3.

- Rudolf Seufert (1993). Nürnberger Land (in German). Hersbruck: Karl Pfeiffer's Buchdruckerei und Verlag. ISBN 3-9800386-5-3.

Coordinates: 49°27′N 11°5′E / 49.450°N 11.083°E