Gordon Campbell

| Gordon Campbell OBC | |

|---|---|

| |

| Canadian High Commissioner to the United Kingdom | |

|

In office September 15, 2011 – July 19, 2016 | |

| Prime Minister |

Stephen Harper Justin Trudeau |

| Preceded by | James R. Wright |

| Succeeded by | Janice Charette |

| 34th Premier of British Columbia | |

|

In office June 5, 2001 – March 14, 2011 | |

| Monarch | Elizabeth II |

| Lieutenant Governor |

Garde Gardom Iona Campagnolo Steven Point |

| Preceded by | Ujjal Dosanjh |

| Succeeded by | Christy Clark |

| Leader of the Opposition in British Columbia | |

|

In office February 17, 1994 – June 5, 2001 | |

| Premier |

Mike Harcourt Glen Clark Dan Miller Ujjal Dosanjh |

| Preceded by | Fred Gingell (acting) |

| Succeeded by | Joy MacPhail |

| Member of the Legislative Assembly of British Columbia | |

|

In office February 17, 1994 – May 28, 1996 | |

| Preceded by | Art Cowie |

| Succeeded by | Colin Hansen |

| Constituency | Vancouver-Quilchena |

|

In office May 28, 1996 – March 15, 2011 | |

| Preceded by | Darlene Marzari |

| Succeeded by | Christy Clark |

| Constituency | Vancouver-Point Grey |

| 35th Mayor of Vancouver | |

|

In office 1986 – September 11, 1993 | |

| Preceded by | Michael Harcourt |

| Succeeded by | Philip Owen |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Gordon Muir Campbell January 12, 1948 Vancouver, British Columbia |

| Nationality | Canadian |

| Political party | British Columbia Liberal Party |

| Spouse(s) | Nancy née Chipperfield |

| Relations | Michael Campbell (brother) |

| Children | 2 |

| Alma mater |

Dartmouth College (BA) Simon Fraser University (MBA) |

| Occupation | Real estate developer, Politician, Teacher, Diplomat |

| Religion | Anglican |

| Signature |

|

Gordon Muir Campbell, OBC (born January 12, 1948) is a Canadian diplomat and politician who was the 35th Mayor of Vancouver from 1986 to 1993 and the 34th Premier of British Columbia from 2001 to 2011. He was the leader of the British Columbia Liberal Party, which was re-elected for a third term on May 12, 2009, and which holds a majority in the Legislative Assembly of British Columbia. From 2011 to 2016, he was the Canadian High Commissioner to the United Kingdom.[1] From 2014 to 2016, he was also Canada’s Representative to the Ismaili Imamat.[2]

Early life

Campbell was born in Vancouver, British Columbia. His father, Charles Gordon (Chargo) Campbell, was a physician and an Assistant Dean of Medicine at the University of British Columbia, until his suicide in 1961[3] when Gordon was 13.[4] His mother Peg was a kindergarten assistant at University Hill Elementary School.[5] Charles and his wife, Peg, had four children. Gordon grew up in West Point Grey and went to Stride Elementary, and University Hill Secondary School[4][5] where he was student council president.[4] While there he was accepted by Dartmouth College, an Ivy League institution in New Hampshire where he had received a scholarship and a job offer so he could afford fees.[4]

Later life

Campbell intended to study medicine but was persuaded by three English professors to shift his focus to English and urban management, earning a BA degree in English.[4] At Dartmouth, in 1969, he received a $1,500 Urban Studies Fellowship that made it possible for him to work in Vancouver’s city government.[4] At that time Campbell met Art Phillips, a city councilor and future mayor of Vancouver.[4]

After graduating from university that year, Campbell and Nancy Chipperfield were married in New Westminster on July 4, 1970.[4] Under the Canadian University Service Overseas program,[6] they went to Nigeria to teach. There he coached basketball and track and field and launched literacy initiatives.[6] Campbell was accepted to Stanford to pursue a master's degree in education, but the couple instead returned to Vancouver where Campbell entered law school at UBC and Nancy completed her education degree.[4] Campbell's law education was short-lived; he soon returned to the City of Vancouver to work for Art Phillips on his mayoral campaign. When Phillips was elected in 1972, Campbell became his executive assistant, a job he held until 1976.[5]

When he left Mayor Phillips's office, at 28 years old, Campbell went to work for Marathon Realty as a project manager.[4] In 1976 Geoffrey, the Campbells' first child, was born. In 1978, the Campbells bought a house in Point Grey, which was their home for the next 26 years.[4] From 1975 to 1978 he pursued his MBA at Simon Fraser University. In 1979, Nancy Campbell gave birth to their second child, Nicholas.[4]

In 1981, Campbell left Marathon Realty and started his own business, Citycore Development Corporation. Despite the economic slowdown that hit Canada that year, Campbell's corporation was successful and constructed several buildings in Vancouver.[7]

After a two-year absence from civic political activities, Campbell became involved in the mayoral campaign of May Brown[8] and was an active supporter of the Downtown Stadium for Vancouver committee. Although Brown was unsuccessful, Campbell and the committee continued promoting the stadium to revitalize False Creek, which at the time was polluted industrial land.[4] The committee was eventually successful, as Premier Bill Bennett announced the Downtown Stadium project in 1980.

Vancouver Councillor and Mayor

Campbell was elected to Vancouver City Council in 1984 and he served as Mayor of Vancouver for three successive terms from 1986 to 1993. Notable events in civic politics during that period included the development of the Expo Lands, the re-development of Yaletown, and the foundation of the Coal Harbour residential area. One of the most significant projects of his term was the construction of the new Vancouver Public Library. He also served as chair of the Greater Vancouver Regional District and president of the Union of British Columbia Municipalities.

Liberal leader

Campbell became leader of the British Columbia Liberal Party in 1993 in a three-way race with Gordon Gibson, Jr. and Gordon Wilson, the incumbent party leader who had lost the confidence of his party, partly due to a romantic affair with a member of his caucus. Campbell was elected to the Legislative Assembly the next year in a Vancouver-Quilchena by-election.

In the 1996 campaign, Campbell was elected to the Vancouver-Point Grey riding, which he held until 2010. The Liberals entered the election leading in polls, due to a fundraising scandal in the NDP. Campbell's party gained 16 seats and won a slight plurality of the popular vote, but the NDP retained enough seats to continue a majority government. Campbell stayed on as Leader of the Opposition, opposing New Democratic Party Premiers Glen Clark, Dan Miller and Ujjal Dosanjh.

In May 2000, Campbell, along with Michael de Jong and Geoffrey Plant, brought a court case against the Nisga'a Nation, the Attorney General of Canada and the Attorney General of British Columbia, parties to the first modern day Aboriginal Treaty in British Columbia, known as the Nisga'a Final Agreement. Campbell and the other plaintiffs claimed that the treaty signed with the Nisga'a Nation was "in part inconsistent with the Constitution of Canada and therefore in part of no force and effect." However, Justice Williamson dismissed the application, judging that the enacting legislation did "establish a treaty as contemplated by Section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982. The legislation and the Treaty are constitutionally valid."[9]

Premier Glen Clark's government was beset by controversy, difficult economic and fiscal conditions and attacks on the NDP's building of the Fast Ferries, and charges against Clark in relation to casino licensing, known as Casinogate (Clark was eventually vindicated, though resigned his post because of the investigation). In the BC election of 2001 Campbell's Liberals defeated the two-term NDP incumbents, taking 77 of 79 seats in the legislature. This was the largest majority of seats, and the second-largest majority of the popular vote in BC history.[10]

First term as Premier

Tax

In 2001, Campbell campaigned on a promise to significantly reduce income taxes to stimulate the economy. A day after taking office, Campbell reduced personal income tax for all taxpayers by 25 per cent.[11] Cuts were applied to every tax bracket. The government also introduced reductions in the corporate income tax, and eliminated the Corporation Capital Tax.

Spending

To finance the tax cuts and to balance the provincial budget, Campbell's first term was also noted for several measures of fiscal austerity. This included reductions in welfare rolls and some social services, deregulation, sale of government assets (in particular the ferries built by the previous government during the Fast Ferry Scandal), reducing the size of the civil service, and closing government offices in certain areas. BC Rail's operations were sold to the Canadian National Railway despite contrary campaign promises (condemned as unfair by the losing bidders and triggered charges based in information found during police raids on cabinet offices in a drug-related investigation in what is known as the BC Legislature Raids).[12][13]

Education

The Campbell government passed legislation in August 2001 declaring education as an essential service, therefore making it illegal for educators to go on strike. This fulfilled a platform promise made in the election campaign.[14]

The government embarked upon the largest expansion of BC's post-secondary education system since the foundation of Simon Fraser University in 1965. In 2004, the government announced that 25,000 new post-secondary places would be established between 2004 and 2010.[15]

The Campbell government also lifted the six-year-long tuition fee freeze that was placed on BC universities and colleges by the previous NDP government. In 2005 a tuition limit policy was put in place, capping increases at the rate of inflation.[16]

Environmental

Campbell made significant changes, including new Environmental Assessment Legislation, as well as controversial new aquaculture policies on salmon farming. In November 2002, Campbell's government passed the Forest and Range Practices Act which reversed many of the regulations previously introduced by the former New Democrat government.

First Nations

During the 2001 election, the BC Liberals also campaigned on a promise to hold a consultative referendum seeking a mandate from the general public to negotiate treaties with First Nations. In the spring of 2002, the government held the referendum.[17]

The referendum, led by Attorney General Geoff Plant, proposed eight questions that voters were asked to either support or oppose. Critics claimed the phrasing was flawed or biased toward a predetermined response. While some critics, especially First Nations and religious groups, called for a boycott of the referendum, by the May 15 deadline almost 800,000 British Columbians had cast their ballots. Critics called for a boycott of the referendum and First Nations groups collected as many ballots as possible so that they might be destroyed publicly.[18]

Of the ballots that were returned, over 80 per cent of participating voters agreeing to all eight proposed principles.[19] Treaty negotiations resumed.

In the lead-up to the 2005 election, Campbell discussed opening up a New Relationship with Aboriginal People.[20] This position was directly opposite to his view of Aboriginal Treaties pursued in the 2000 Nisga'a Final Treaty court case, discussed above. The "New Relationship" became the foundation for agreements in principle that were made during the second term, but ultimately rejected by the membership of the First Nations involved.

Health care

Early in its first term, without consulting with labour unions,[21] the Campbell government passed legislation (Bill 29, the Health and Social Services Delivery Improvement Act) that unilaterally amended labour agreements and required health authorities to contract out positions when savings could be predicted. This led to the privatization of more than 8,000 healthcare jobs.[22][23][24] These changes met resistance from many health care workers and resulted in a strike by some of them. This strike was ended by court order and amendments by the government on parts of the legislation.[25] The unions took the issue to the Supreme Court of Canada which ruled in 2007 that the Act violated 'good faith' requirements for collective bargaining.[22]

The Campbell government increased health funding by $3 billion during its first term in office to help meet the demand at hand and to increase wages for some health professionals.[26] As well they increased the number of new nurse training spaces by 2,500, an increase of 62 percent.[27] At the same time, it nearly doubled the doctors in training, and opened new medical training facilities in Victoria and Prince George.[28]

Wage rates for doctors and nurses increased in the Campbell government’s first term. Nurses received a 23.5 percent raise while doctors received a 20.6 percent raise after arbitration.[29][30] Doctors had threatened to go on strike due to the original Campbell plan to slash their fees, which was seen as a breach of contract, with the dispute being sent to arbitration.

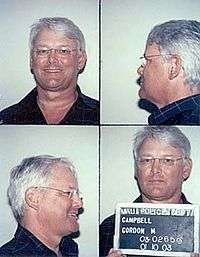

Impaired driving

In January 2003, after visiting broadcaster Fred Latremouille, Campbell was arrested and pleaded no contest for driving under the influence of alcohol while vacationing in Hawaii. According to court records Campbell's blood-alcohol level was more than twice the legal limit. In Hawaii, drunk driving is only a misdemeanour, in Canada it is a Criminal Code offence. As is customary in the United States, Campbell's mugshot was provided to the media by Hawaiian police. The image has proved to be a lasting personal embarrassment, frequently used by detractors and opponents. Campbell was fined $913 (US) and the court ordered him to take part in a substance abuse program, and to be assessed for alcoholism.[31]

A national anti-drinking and driving group, Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD) Canada called for Campbell to resign.[32]

Minimum wage

On November 1, 2001, the Campbell BC Liberals honoured the previous NDP government's legislation to increase the minimum wage to $8.00 per hour from $7.60, while at the same time authority was given so new entrants into the labour force could be paid $6 per hour, 25% lower than the minimum wage. In 2010, British Columbia had the lowest minimum wage amongst the 13 provinces and territories. Campbell's successor, Christy Clark, announced that the minimum wage would increase in three stages to begin on May 1, 2011.[33]

2010 Winter Olympics

British Columbia won the right to host the 2010 Winter Olympics on July 2, 2003. This was a joint Winter Olympics bid by Vancouver and the ski resort of Whistler.[34] Campbell attended the final presentations in Prague, the Czech Republic.

On February 12, 2010, Campbell was in attendance at the opening ceremony for the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver and attended events during the games and was present at the closing ceremony.

On April 23, 2010, Campbell received the Olympic Order from the Canadian Olympic Committee for being a dedicated proponent of the Olympic Movement.[35]

Second term as Premier

In the May 17, 2005, election, Campbell and the BC Liberals won a second majority government with a reduced majority.

Economy

430,000 new jobs have been created in B.C. since December 2001,[36] the best job creation record in Canada. In 2007, the economy created 70,800 more jobs, almost all full-time positions.[36] By Spring 2007, unemployment had fallen to 4.0%, the lowest rate in 30 years. However, 40,300 jobs were lost in 2008, mostly in December (35,100), and unemployment rates sit at 7.8% as of July 2009,[37] the same level they were at in July 2001.[38]

Education

On October 7, 2005, following the successive imposition of contracts on BC teachers, British Columbia's teachers began an indefinite walk-out. Campbell having made striking illegal for teachers, educators referred to this as an act of civil disobedience. Despite fines and contempt charges, the teachers' walk-out lasted two weeks, and threatened to culminate in a general strike across the province.

Environmental

In 2008, Premier Campbell's government developed and entrenched in law the Climate Action Plan.[39] The Plan is claimed by the government to be one of the most progressive plans to address greenhouse gas emissions in North America, due in part to the revenue-neutral carbon tax.[40]

Gordon Campbell, told Tim Flannery that he introduced the carbon tax in British Columbia after reading his book The Weather Makers (2005).[41]

First Nations

The Campbell government attempted to negotiate treaties with a number of First Nations in its second term. Final agreements in principle were signed with the Tsawwassen First Nation,[42] Maa-nulth Treaty Society,[43] and Lheidli T’enneh First Nations.[44] The Tsawwassen Treaty was passed by the band's membership in a heavily contested and divisive referendum but came into effect on April 3, 2009.[45]

The Maa-nulth Treaty, which covers a group of Nuu-chah-nulth band governments, is pending ratification by the federal government[46] while the Lheidli-T'enneh Treaty was rejected in the referendum held by that band.

Health care

The Campbell government launched the Conversation on Health, a province-wide consultation with British Columbians on their health care to lay the groundwork for changes to the principles of the Canada Health Act that were presented in the Fall of 2007.[47]

Third term as Premier

Campbell and the BC Liberals were re-elected in the May 12, 2009, election. Their share of total seats remained almost unchanged, as they won 49 seats in a new expanded 85-seat legislature.

BC Rail e-mail controversy

Some five years after the BC Legislature Raids, controversy arose when it was revealed that e-mails among Campbell, his staff, and other cabinet ministers may not have been deleted years ago as first claimed.[48] An affidavit filed by Rosemarie Hayes, the B.C. government's manager in charge of information services, suggested that copies of the e-mails may have existed as recently as May 2009, but were ordered to have been destroyed at that time.[49]

On July 20, 2009, the Supreme Court of British Columbia judge conducting the Basi-Virk trial, Madam Justice Elizabeth Bennett, ordered Campbell and other top officials to turn over their e-mail records to the court by August 17.[50] These were never located nor surrendered to the Court.

HST controversy

On July 23, 2009, Campbell announced that British Columbia would move towards a Harmonized Sales Tax, or HST.[51] The new 12% sales tax would combine and replace the previous 5% Goods and Services Tax and 7% Provincial Sales Tax. The announcement was met with strong opposition from political opponents,[52] news media,[53][54] and opposition from most members of the public.[55][56] However, the proposed tax received a positive reaction from the business community, strong supporters of the BC Liberals.[57] Much of the opposition stemmed from Campbell's perceived dishonesty about the HST as his government had said it was not on their radar prior to the election, and the fact that it equated to a tax hike for several sectors.[58]

On August 24, representatives from the retail, resource, and film industries held a news conference to speak out in favour of harmonizing BC's sales taxes.[59] In addition, sales tax harmonization has been hailed by the C.D. Howe Institute, a think tank, as being "crucial for B.C to maintain its economic competitiveness."[60]

On June 11, 2010, Blair Lekstrom resigned as BC's Minister of Energy, Mines and Petroleum Resources, saying he was leaving both the cabinet and the caucus over a fundamental disagreement with the BC Liberals on the harmonized sales tax.[61]

A freedom of information request came to light on September 1, 2010, revealing that the BC Liberals had formed HST-related plans prior to the 2009 election—contrary to their statements on the subject.[62]

Resignation

On November 3, 2010, Campbell made a televised address to the public, announcing his intention to resign as Premier of British Columbia. The announcement was made after months of strong political opposition to the implementation of the HST,[63] which saw Campbell's approval rating fall to only 9%, according to an Angus Reid poll,[64] and led to rumours that he has lost support of some members of his cabinet.[65] Another factor in his resignation was the ongoing BC Rail Scandal trial in which the Premier and other members of his cabinet and staff were due to face embarrassing cross-examination in relation to the Basi-Virk trial, which was called to a halt with an illegal plea bargain around the same time. On December 5, 2010, while answering questions from reporters, he "hinted strongly" that he will not stay on as an MLA after his successor as Liberal leader is chosen in February, according to Rod Mickleburgh of The Globe and Mail.[66] Campbell resigned as premier on March 14, 2011, he was succeeded by Christy Clark but remained in party circles as "senior advisor".

High Commissioner to the UK

In late June 2011 it was reported that Campbell was to be named Canadian High Commissioner to the United Kingdom.[67] On August 15, 2011, Campbell was formally announced to succeed the post. On September 15, 2011, Campbell officially became the Canadian High Commissioner in London. He represents Canadian interests throughout Britain.

Campbell was shortlisted for the Grassroot Diplomat Initiative Award in 2015 for his work on business partnership as the High Commissioner of Canada, and he remains in the directory of the Grassroot Diplomat Who's Who publication.[68]

Honours

On September 2, 2011, it was announced that Campbell would receive the Order of British Columbia, the second Premier to be a recipient.[69] Some believed his nomination contravened the legislation that prevented an elected official from being appointed while holding office. However, on September 7, 2011, Lance S. G. Finch, the Chief Justice of British Columbia and chair of the Order of BC Advisory Council declared that although his nomination package was received on March 10, 2011 (four days before his resignation as Premier), Campbell was appointed to the Order on September 2, 2011 at which time he was not an elected MLA.[70]

In 2014, Thompson Rivers University gave Campbell the Honorary degree of Doctor of Laws due to his contributions to the founding of their newly opened law school.[71] [72]

He was awarded the Queen Elizabeth II Golden Jubilee Medal in 2002 and the Queen Elizabeth II Diamond Jubilee Medal in 2012.

Election results (partial)

| British Columbia general election, 2009: Vancouver-Point Grey | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | Expenditures | ||||

| Liberal | Gordon Campbell | 11,546 | 50.38 | $154,282 | ||||

| New Democratic | Mel Lehan | 9,232 | 40.28 | $128,634 | ||||

| Green | Stephen Kronstein | 2,012 | 8.78 | $1,405 | ||||

| Sex | John Ince | 130 | 0.56% | $250 | ||||

| Total Valid Votes | 22,920 | 100 | ||||||

| Total Rejected Ballots | 134 | 0.58 | ||||||

| Turnout | 23,054 | 55.98 | ||||||

References

- ↑ Diplomatic Appointments Archived March 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Diplomatic Appointments Archived October 16, 2015, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Chris Wood. "''Maclean's Magazine'' article in ''The Canadian Encyclopedia''". Thecanadianencyclopedia.com. Retrieved November 29, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Bula, Frances (April 28, 2001). The Vancouver Sun. Vancouver,BC. p. D3. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - 1 2 3 Wood, Chris (1999). Macleans. 112 (18) http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.com/index.cfm?PgNm=TCE&Params=M1ARTM0011952. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - 1 2 "Gordon Campbell". Maple Leaf Web.

- ↑ Lee, Jeff (April 16, 2005). "For the premier, it's all about change". The Vancouver Sun. Vancouver,BC. p. C3.

- ↑ www.orderofbc.gov.bc.ca Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ 2000 BCSC 1123

- ↑ Electoral History of British Columbia 1871–1986 Archived June 13, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved 2007-03-16.

- ↑ McMartin, Will (April 24, 2010). "How Libs Made BC Rail's True Value a Fake Train Wreck". The Tyee. Retrieved December 11, 2010.

- ↑ McMartin, Will (March 29, 2010). "Liberals, Stop Lying about BC Rail". The Tyee. Retrieved December 11, 2010.

- ↑ Ministry of Skills Development and Labour (August 14, 2001). "Government Honours Labour Commitments". .news.gov.bc.ca. Retrieved November 29, 2010.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on April 15, 2007. Retrieved 2007-03-16.

- ↑ "Tuition Fees – Ministry of Advanced Education and Labour Market Development". Aved.gov.bc.ca. Retrieved November 29, 2010.

- ↑ "B.C. treaty referendum" Archived January 18, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. – CBC, July 2, 2002

- ↑ Hon, Dee (May 18, 2005). "The Orphaning of STV". The Tyee. Retrieved December 11, 2010.

- ↑ Johnson, Linda (September 9, 2002). "Report of the Chief Electoral Officer on the Treaty Negotiations Referendum" (PDF). Elections BC. Retrieved December 11, 2010.

- ↑ "New Relationship". Gov.bc.ca. April 2, 2008. Retrieved November 29, 2010.

- ↑ "(2007 SCC 27) Health Services and Support - Facilities Subsector Bargaining Assn. v. British Columbia". Supreme Court of Canada. June 8, 2007. Retrieved 28 June 2014.

- 1 2 "Big win for unions as ruling says bargaining protected". CBC. June 8, 2007. Retrieved 28 June 2014.

- ↑ "Neoliberalism and working-class resistance in British Columbia: the hospital employees' union Struggle, 2002–2004". Labour/Le Travail. March 22, 2006.

- ↑ http://search.proquest.com/docview/242509433[]

- ↑ "Hospital workers vote for privatization settlement". CTV. February 22, 2008. Retrieved March 19, 2012.

- ↑ "Balanced Budget 2005 – Province of British Columbia". Bcbudget.gov.bc.ca. February 15, 2005. Retrieved November 29, 2010.

- ↑ "http://www.northernhealth.ca:80/News_Events/Media_Centre_and_News/20060511UNBCnursinggrads.asp – cannot be found.". Northernhealth.ca. Retrieved November 29, 2010. External link in

|title=(help) - ↑ "Medical Training Expansion – Ministry of Advanced Education and Labour Market Development". Aved.gov.bc.ca. Retrieved November 29, 2010.

- ↑ Office of the Premier, Ministry of Skills Development and Labour (August 7, 2001). "Legislation To End Health-Care Disputes". .news.gov.bc.ca. Retrieved November 29, 2010.

- ↑ Ministry of Health Services (March 5, 2002). "DOCTORS TO RECEIVE 20.6% INCREASE, ARBITRATION ENDED". .news.gov.bc.ca. Retrieved November 29, 2010.

- ↑ "B.C. premier fined for drunk driving". CBC News. March 24, 2003.

- ↑ "B.C. premier should quit over drunk driving charge: MADD". CBC News. January 12, 2003. Retrieved March 29, 2014.

- ↑ "Premier announces increase to minimum wage". Retrieved September 11, 2011.

- ↑ "2010 Winter Olympics – Vancouver, Home of the Winter Olympic Games in 2010". Vec.ca. Retrieved November 29, 2010.

- ↑ "The Honourable Gordon Campbell to Receive Canadian Olympic Order". Newswire.ca. November 24, 2010. Retrieved November 29, 2010.

- 1 2 "Positive Economic Indicators – Province of British Columbia". Gov.bc.ca. Retrieved November 29, 2010.

- ↑ "Latest release from the Labour Force Survey. Friday, November 5, 2010". Statcan.ca. November 5, 2010. Retrieved November 29, 2010.

- ↑ "The BC Labour Market in 2001" (PDF). Retrieved November 29, 2010.

- ↑ "LiveSmart BC – Climate Action Plan". Livesmartbc.ca. September 30, 2008. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ↑ "Balanced Budget 2008 Backgrounder – Province of British Columbia". Bcbudget.gov.bc.ca. February 19, 2008. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ↑ Tim Flannery, Atmosphere of Hope. Solutions to the Climate Crisis, Penguin Books, 2015, page 5 (ISBN 9780141981048).

- ↑ Office of the Premier, Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (December 8, 2006). "Tsawwassen news release". .news.gov.bc.ca. Retrieved November 29, 2010.

- ↑ Office of the Premier, Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (December 9, 2006). "Maa-nulth news release". .news.gov.bc.ca. Retrieved November 29, 2010.

- ↑ Government Caucus. "Lheidli T'enneh news release". Governmentcaucus.bc.ca. Retrieved November 29, 2010.

- ↑ "Now and Everlasting", Terry Glavin, Vancouver Magazine, March 26, 2009 Archived November 8, 2014, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Maa-nulth Treaty Society page". Maanulth.ca. Retrieved November 29, 2010.

- ↑ Office of the Premier, Ministry of Health (September 28, 2006). "British Columbians To Help Shape Future Of Health". .news.gov.bc.ca. Retrieved November 29, 2010.

- ↑ Fraser, Keith (June 23, 2009). "Basi-Virk defence queries missing B.C. Rail e-mails". Theprovince.com. Retrieved November 29, 2010.

- ↑

- ↑ "This page is available to GlobePlus subscribers". The Globe and Mail. Toronto. Archived from the original on July 24, 2009. Retrieved November 29, 2010.

- ↑ "B.C. moves to 12 per cent HST". CBC News. July 23, 2009. Retrieved March 29, 2014.

- ↑ "Surprise decision on new tax could kill tourism, service jobs | BC NDP". Bcndp.ca. Retrieved November 29, 2010.

- ↑

- ↑ "Story – News – Victoria Times Colonist". Timescolonist.com. Retrieved November 29, 2010.

- ↑ Global BC; Ipsos Reid: Wednesday, August 5, 2009 (August 5, 2009). "Ipsos Reid/Global News HST Poll". Globaltvbc.com. Retrieved November 29, 2010.

- ↑ Angus Reid Public Opinion. "Angus Reid Public Opinion". Vision Critical. Retrieved November 29, 2010.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on August 17, 2009. Retrieved 2009-08-27.>

- ↑ Tieleman, Bill (June 1, 2010). "HST Hits and Myths". The Tyee. Retrieved December 10, 2010.

- ↑ Archived August 29, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Story – News". Vancouver Sun. November 25, 2010. Retrieved November 29, 2010.

- ↑ "Blair Lekstrom Resigns". Globe and Mail. Toronto. Archived from the original on September 1, 2010. Retrieved November 29, 2010.

- ↑ Shaw, Rob (September 2, 2010). "Senior B.C. officials discussed the HST before the election, documents reveal". Times Colonist. Retrieved November 29, 2010.

- ↑ MacLeod, Andrew (November 3, 2010). "'Politics Can Be a Nasty Business': Campbell Steps Down". The Tyee. Retrieved December 10, 2010.

- ↑ Burgess, Steve (October 19, 2010). "Nine Per Cent Gordo". The Tyee. Retrieved December 10, 2010.

- ↑ "B.C. Premier Campbell stepping down". CBC. November 3, 2010. Retrieved March 29, 2014.

- ↑ Mickleburgh, Rod (December 5, 2010). "Gordon Campbell hints he'll step down as MLA". Globe and Mail. Toronto. Retrieved December 6, 2010.

- ↑ "Gordon Campbell to be high commissioner to Britain". CBC News. June 23, 2011.

- ↑ "Grassroot Diplomat Who's Who". Grassroot Diplomat. 15 March 2015. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ↑ News | Order of BC Archived September 27, 2016, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on March 23, 2012. Retrieved 2011-09-08.

- ↑ Williams, Adam (June 16, 2014). "Gordon Campbell receives honorary law degree, delivers TRU convocation address". Globe and Mail. Retrieved 28 June 2014.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on June 13, 2015. Retrieved 2015-06-12.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gordon Campbell. |

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Gordon Wilson |

Leader of the Opposition In British Columbia 1993–2001 |

Succeeded by Joy MacPhail |

| Order of precedence | ||

| Preceded by Ujjal Dosanjh, Former Premier of British Columbia |

Order of precedence in British Columbia as of 2013 |

Succeeded by Linda Reid, The Speaker of the Legislative Assembly of British Columbia |