Listeriosis

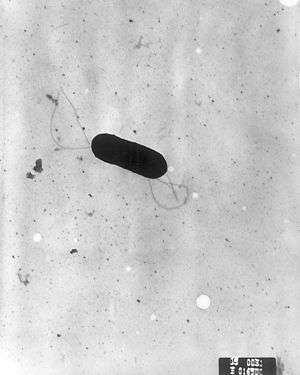

| Listeriosis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Listeria monocytogenes | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| ICD-10 | A32 |

| ICD-9-CM | 027.0 |

| DiseasesDB | 7503 |

| MedlinePlus | 001380 |

| eMedicine | med/1312 ped/1319 |

| Patient UK | Listeriosis |

| MeSH | D008088 |

| Orphanet | 533 |

Listeriosis is a bacterial infection most commonly caused by Listeria monocytogenes,[1] although L. ivanovii and L. grayi have been reported in certain cases. Listeria primarily causes infections of the central nervous system (meningitis, meningoencephalitis, brain abscess, cerebritis) and bacteremia in those who are immunocompromised,[2] pregnant women, and those at the extremes of age (newborns and the elderly), as well as gastroenteritis in healthy persons who have been severely infected. Listeria is ubiquitous and is primarily transmitted via the oral route after ingestion of contaminated food products, after which the organism penetrates the intestinal tract to cause systemic infections. The diagnosis of listeriosis requires the isolation of the organism from the blood and/or the cerebrospinal fluid. Treatment includes prolonged administration of antibiotics, primarily ampicillin and gentamicin, to which the organism is usually susceptible.

Signs and symptoms

The disease primarily affects older adults, persons with weakened immune systems, pregnant women, and newborns. Rarely, people without these risk factors can also be affected. A person with listeriosis usually has fever and muscle aches, often preceded by diarrhea or other gastrointestinal symptoms. Almost everyone who is diagnosed with listeriosis has invasive infection (meaning that the bacteria spread from their intestines to their blood stream or other body sites). Disease may occur as much as two months after eating contaminated food.

The symptoms vary with the infected person:

- High-risk persons other than pregnant women: Symptoms can include fever, muscle aches, headache, stiff neck, confusion, loss of balance, and convulsions.

- Pregnant women: Pregnant women typically experience only a mild, flu-like illness. However, infections during pregnancy can lead to miscarriage, stillbirth, premature delivery, or life-threatening infection of the newborn.

- Previously healthy persons: People who were previously healthy but were exposed to a very large dose of Listeria can develop a non-invasive illness (meaning that the bacteria have not spread into their blood stream or other body sites). Symptoms can include diarrhea and fever.

If an animal has eaten food contaminated with Listeria and does not have any symptoms, most experts believe that no tests or treatment are needed, even for people at high risk for listeriosis.[3]

Cause

Listeria monocytogenes is ubiquitous in the environment. The main route of acquisition of Listeria is through the ingestion of contaminated food products. Listeria has been isolated from raw meat, dairy products, vegetables, fruit and seafood. Soft cheeses, unpasteurized milk and unpasteurised pâté are potential dangers; however, some outbreaks involving post-pasteurized milk have been reported.[1]

Rarely listeriosis may present as cutaneous listeriosis. This infection occurs after direct exposure to L. monocytogenes by intact skin and is largely confined to veterinarians who are handling diseased animals, most often after a listerial abortion.[4]

Diagnosis

In CNS infection cases, L. monocytogenes can often be cultured from the blood or from the CSF (Cerebrospinal fluid).[5]

Prevention

The main means of prevention is through the promotion of safe handling, cooking and consumption of food. This includes washing raw vegetables and cooking raw food thoroughly, as well as reheating leftover or ready-to-eat foods like hot dogs until steaming hot.[6]

Another aspect of prevention is advising high-risk groups such as pregnant women and immunocompromised patients to avoid unpasteurized pâtés and foods such as soft cheeses like feta, Brie, Camembert cheese, and bleu. Cream cheeses, yogurt, and cottage cheese are considered safe. In the United Kingdom, advice along these lines from the Chief Medical Officer posted in maternity clinics led to a sharp decline in cases of listeriosis in pregnancy in the late 1980s.[7]

Treatment

Bacteremia should be treated for 2 weeks, meningitis for 3 weeks, and brain abscess for at least 6 weeks. Ampicillin generally is considered antibiotic of choice; gentamicin is added frequently for its synergistic effects. Overall mortality rate is 20–30%; of all pregnancy-related cases, 22% resulted in fetal loss or neonatal death, but mothers usually survive.[8]

Epidemiology

_409-14%2C_Figure_1.png)

Incidence in 2004–2005 was 2.5–3 cases per million population a year in the United States, where pregnant women accounted for 30% of all cases.[9] Of all nonperinatal infections, 70% occur in immunocompromised patients. Incidence in the U.S. has been falling since the 1990s, in contrast to Europe where changes in eating habits have led to an increase during the same time. In Sweden, it has stabilized at around 5 cases per annum per million population, with pregnant women typically accounting for 1–2 of some 40 total yearly cases.[10]

There are four distinct clinical syndromes:

- Infection in pregnancy: Listeria can proliferate asymptomatically in the vagina and uterus. If the mother becomes symptomatic, it is usually in the third trimester. Symptoms include fever, myalgias, arthralgias and headache. Miscarriage, stillbirth and preterm labor are complications of this infection. Symptoms last 7–10 days.

- Neonatal infection (granulomatosis infantiseptica): There are two forms. One, an early-onset sepsis, with Listeria acquired in utero, results in premature birth. Listeria can be isolated in the placenta, blood, meconium, nose, ears, and throat. Another, late-onset meningitis is acquired through vaginal transmission, although it also has been reported with caesarean deliveries.

- Central nervous system (CNS) infection: Listeria has a predilection for the brain parenchyma, especially the brain stem, and the meninges. It can cause cranial nerve palsies, encephalitis, meningitis, meningoencephalitis and abscesses. Mental status changes are common. Seizures occur in at least 25% of patients.

- Gastroenteritis: L. monocytogenes can produce food-borne diarrheal disease, which typically is noninvasive. The median incubation period is 21 days, with diarrhea lasting anywhere from 1–3 days. Patients present with fever, muscle aches, gastrointestinal nausea or diarrhea, headache, stiff neck, confusion, loss of balance, or convulsions.

Listeria has also been reported to colonize the hearts of some patients. The overall incidence of cardiac infections caused by Listeria is relatively low, with 7-10% of case reports indicating some form of heart involvement. There is some evidence that small subpopulations of clinical isolates are more capable of colonizing the heart throughout the course of infection, but cardiac manifestations are usually sporadic and may rely on a combination of bacterial factors and host predispositions, as they do with other strains of cardiotropic bacteria.[11]

Recent outbreaks

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) there are about 1,600 cases of listeriosis annually in the United States. Compared to 1996-1998, the incidence of listeriosis had declined by about 38% by 2003. However, illnesses and deaths continue to occur. On average from 1998-2008, 2.4 outbreaks per year were reported to the CDC. A large outbreak occurred in 2002, when 54 illnesses, 8 deaths, and 3 fetal deaths in 9 states were found to be associated with consumption of contaminated turkey deli meat.[12]

The 2008 Canadian listeriosis outbreak, an outbreak of listeriosis in Canada linked to a Maple Leaf Foods plant in Toronto, Ontario killed 22 people.[13]

On March 13, 2015, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that State and local health officials, CDC, and FDA are collaborating to investigate an outbreak of Listeria.[14] The joint investigation found that certain Blue Bell brand ice cream products are the likely source for some or all of these illnesses. Upon further investigation the CDC claimed Blue Bell ice cream had evidence of listeria bacteria in its Oklahoma manufacturing plant as far back as March 2013, which led to 3 deaths in Kansas.[15]

On March 14, 2015, an outbreak of listeriosis in Kansas was linked to certain Blue Bell Ice Cream products (Blue Bell Chocolate Chip Country Cookies, Great Divide Bars, Sour Pop Green Apple Bars, Cotton Candy Bars, Scoops, Vanilla Stick Slices, Almond Bars, and No Sugar Added Moo Bars). Blue Bell, the nation's third most popular ice cream brand, says its regular Moo Bars were untainted, as were its ice cream varieties in three-gallon, half-gallon, quart, pint and single-serving containers and its take-home frozen snack novelties. It was the first outbreak of a foodborne illness in the company's history. The items came from the company's production facility located in Broken Arrow, Oklahoma, according to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), in Washington, D.C. The Atlanta-based U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), also a branch of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), stated that all five of the sickened individuals, including the three who have died (60% mortality rate) were receiving treatment at the same Kansas hospital before developing the listeriosis, suggesting their infections with the Listeria bacteria were nosocomial (acquired, while eating the products, in the hospital). That might also help to explain the higher mortality rate in these cases (60%, versus the more normal 20%-30%): the people, who were all older (three of the five were women) were already hospitalized.[16][17][18]

On April 20, 2015, Blue Bell issued a voluntary recall of all its products, citing further internal testing that found Listeria monocytogenes in an additional half gallon of ice cream from the Brenham facility.[19]

2011 United States listeriosis outbreak

On September 14, 2011, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration warned consumers not to eat cantaloupes shipped by Jensen Farms from Granada, Colorado due to a potential link to a multi-state outbreak of listeriosis. At that time Jensen Farms voluntarily recalled cantaloupes shipped from July 29 through September 10, and distributed to at least 17 states with possible further distribution. The CDC reported that at least 22 people in seven states had been infected as of September 14.[20]

On September 26, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that a total of 72 persons had been infected with the four outbreak-associated strains of Listeria monocytogenes which had been reported to the CDC from 18 states. All illnesses started on or after July 31, 2011 and by September 26, thirteen deaths had been reported: 2 in Colorado, 1 in Kansas, 1 in Maryland, 1 in Missouri, 1 in Nebraska, 4 in New Mexico, 1 in Oklahoma, and 2 in Texas.[21][22] On September 30, 2011, a random sample of romaine lettuce taken by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration tested positive for listeria on lettuce shipped on September 12 and 13 by an Oregon distributor to at least two other states—Washington and Idaho.[23]

By October 18, the CDC reported that 12 states are now linked to listeria in cantaloupe and that 123 people have been sickened and a total of 25 have died. While the tainted cantaloupes should be off store shelves by now, the number of illnesses may still continue to grow. The CDC confirmed a sixth death in Colorado and a second in New York; Indiana, Kansas, Louisiana, Maryland, Missouri, Nebraska, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Texas and Wyoming have also reported deaths.[24]

A final count on December 8 put the death toll at 30: Colorado (8), Indiana (1), Kansas (3), Louisiana (2), Maryland (1), Missouri (3), Nebraska (1), New Mexico (5), New York (2), Oklahoma (1), Texas (2), and Wyoming (1). Among persons who died, ages ranged from 48 to 96 years, with a median age of 82.5 years. In addition, one woman pregnant at the time of illness had a miscarriage.[25]

See also

- List of United States foodborne illness outbreaks

- 2008 Canadian listeriosis outbreak

- 2014 Macedonia listeriosis outbreak

- Listeriosis in animals

References

- 1 2 Ryan KJ; Ray CG, eds. (2003). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. ISBN 0-8385-8529-9.

- ↑ Hof H (1996). Baron S; et al., eds. Listeria Monocytogenes in: Baron's Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). Univ of Texas Medical Branch. ISBN 0-9631172-1-1. (via NCBI Bookshelf).

- ↑ "CDC - Multistate Outbreak of Listeriosis Linked to Whole Cantaloupes from Jensen Farms, Colorado". Cdc.gov. September 27, 2011. Retrieved June 21, 2013.

- ↑ Swaminathan B, Gerner-Smidt P. 2007. The epidemiology of human listeriosis. Microbes In name="Mazza2002">Joseph Mazza (15 January 2002). Manual of clinical hematology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 127–. ISBN 978-0-7817-2980-2. Retrieved 29 June 2010.

- ↑ Connie R. Mahon; Donald C. Lehman; George Manuselis Jr. (25 March 2014). Textbook of Diagnostic Microbiology. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 357–. ISBN 978-0-323-29262-7.

- ↑ "CDC - Prevention - Listeriosis". CDC.gov. Retrieved September 29, 2011.

- ↑ Skinner; et al. (1996). "Listeria: the state of the science Rome 29–30 June 1995 Session IV: country and organizational postures on Listeria monocytogenes in food Listeria: UK government's approach". 7. Food control: 245–247.

- ↑ Health authorities link 12 deaths to contaminated meat (February 2007) Retrieved 23 May 2014

- ↑ Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy, University of Minnesota –Listeriosis

- ↑ Smittskyddsinstitutet –Statistik för listeriainfektion

- ↑ Alonzo F, Bobo LD, Skiest DJ, Freitag NE (April 2011). "Evidence for subpopulations of Listeria monocytogenes with enhanced invasion of cardiac cells". J. Med. Microbiol. 60 (Pt 4): 423–34. doi:10.1099/jmm.0.027185-0. PMC 3133665

. PMID 21266727.

. PMID 21266727. - ↑ "CDC - Statistics - Listeriosis". Cdc.gov. Retrieved June 21, 2013.

- ↑ Weatherill, S. (2009). "Report of the Independent Investigator into the 2008 Listeriosis outbreak" (PDF). Government of Canada. p. vii. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ http://www.msn.com/en-us/news/us/3-kansas-hospital-patients-die-of-ice-cream-related-illness/ar-AA9K0lv

- ↑ http://www.cdc.gov/listeria/outbreaks/ice-cream-03-15/index.html

- ↑ http://www.fda.gov/Food/RecallsOutbreaksEmergencies/Outbreaks/ucm438104.htm

- ↑ http://cdn.bluebell.com/ceo-video-message

- ↑ "FDA warns consumers not to eat Rocky Ford Cantaloupes shipped by Jensen Farms". Fda.gov. Retrieved June 21, 2013.

- ↑ "CDC - Outbreaks Involving Listeriosis - Listeriosis". Cdc.gov. Retrieved June 21, 2013.

- ↑ "Colorado cantaloupes kill up to 16 in listeria outbreak". BBC News. September 28, 2011.

- ↑ "Listeria Found in Lettuce, Too". Abcnews.go.com. 2011-09-30. Retrieved June 21, 2013.

- ↑ Associated Press (October 18, 2011). "25 now dead in listeria outbreak in cantaloupe". .timesdispatch.com. Retrieved June 21, 2013.

- ↑ Multistate Outbreak of Listeriosis Linked to Whole Cantaloupes from Jensen Farms, Colorado - December 8, 2011 (FINAL Update). Retrieved 14 August 2012