Graph partition

In mathematics, the graph partition problem is defined on data represented in the form of a graph G = (V,E), with V vertices and E edges, such that it is possible to partition G into smaller components with specific properties. For instance, a k-way partition divides the vertex set into k smaller components. A good partition is defined as one in which the number of edges running between separated components is small. Uniform graph partition is a type of graph partitioning problem that consists of dividing a graph into components, such that the components are of about the same size and there are few connections between the components. Important applications of graph partitioning include scientific computing, partitioning various stages of a VLSI design circuit and task scheduling in multi-processor systems.[1] Recently, the graph partition problem has gained importance due to its application for clustering and detection of cliques in social, pathological and biological networks. For a survey on recent trends in computational methods and applications see Buluc et al. (2013).[2]

Problem complexity

Typically, graph partition problems fall under the category of NP-hard problems. Solutions to these problems are generally derived using heuristics and approximation algorithms.[3] However, uniform graph partitioning or a balanced graph partition problem can be shown to be NP-complete to approximate within any finite factor.[1] Even for special graph classes such as trees and grids, no reasonable approximation algorithms exist,[4] unless P=NP. Grids are a particularly interesting case since they model the graphs resulting from Finite Element Model (FEM) simulations. When not only the number of edges between the components is approximated, but also the sizes of the components, it can be shown that no reasonable fully polynomial algorithms exist for these graphs.[4]

Problem

Consider a graph G = (V, E), where V denotes the set of n vertices and E the set of edges. For a (k,v) balanced partition problem, the objective is to partition G into k components of at most size v·(n/k), while minimizing the capacity of the edges between separate components.[1] Also, given G and an integer k > 1, partition V into k parts (subsets) V1, V2, ..., Vk such that the parts are disjoint and have equal size, and the number of edges with endpoints in different parts is minimized. Such partition problems have been discussed in literature as bicriteria-approximation or resource augmentation approaches. A common extension is to hypergraphs, where an edge can connect more than two vertices. A hyperedge is not cut if all vertices are in one partition, and cut exactly once otherwise, no matter how many vertices are on each side. This usage is common in electronic design automation.

Analysis

For a specific (k, 1 + ε) balanced partition problem, we seek to find a minimum cost partition of G into k components with each component containing maximum of (1 + ε)·(n/k) nodes. We compare the cost of this approximation algorithm to the cost of a (k,1) cut, wherein each of the k components must have exactly the same size of (n/k) nodes each, thus being a more restricted problem. Thus,

We already know that (2,1) cut is the minimum bisection problem and it is NP complete.[5] Next we assess a 3-partition problem wherein n = 3k, which is also bounded in polynomial time.[1] Now, if we assume that we have an finite approximation algorithm for (k, 1)-balanced partition, then, either the 3-partition instance can be solved using the balanced (k,1) partition in G or it cannot be solved. If the 3-partition instance can be solved, then (k, 1)-balanced partitioning problem in G can be solved without cutting any edge. Otherwise if the 3-partition instance cannot be solved, the optimum (k, 1)-balanced partitioning in G will cut at least one edge. An approximation algorithm with finite approximation factor has to differentiate between these two cases. Hence, it can solve the 3-partition problem which is a contradiction under the assumption that P = NP. Thus, it is evident that (k,1)-balanced partitioning problem has no polynomial time approximation algorithm with finite approximation factor unless P = NP.[1]

The planar separator theorem states that any n-vertex planar graph can be partitioned into roughly equal parts by the removal of O(√n) vertices. This is not a partition in the sense described above, because the partition set consists of vertices rather than edges. However, the same result also implies that every planar graph of bounded degree has a balanced cut with O(√n) edges.

Graph partition methods

Since graph partitioning is a hard problem, practical solutions are based on heuristics. There are two broad categories of methods, local and global. Well known local methods are the Kernighan–Lin algorithm, and Fiduccia-Mattheyses algorithms, which were the first effective 2-way cuts by local search strategies. Their major drawback is the arbitrary initial partitioning of the vertex set, which can affect the final solution quality. Global approaches rely on properties of the entire graph and do not rely on an arbitrary initial partition. The most common example is spectral partitioning, where a partition is derived from the spectrum of the adjacency matrix.

Multi-level methods

A multi-level graph partitioning algorithm works by applying one or more stages. Each stage reduces the size of the graph by collapsing vertices and edges, partitions the smaller graph, then maps back and refines this partition of the original graph.[6] A wide variety of partitioning and refinement methods can be applied within the overall multi-level scheme. In many cases, this approach can give both fast execution times and very high quality results. One widely used example of such an approach is METIS,[7] a graph partitioner, and hMETIS, the corresponding partitioner for hypergraphs.[8]

Spectral partitioning and spectral bisection

Given a graph with adjacency matrix , where an entry implies an edge between node and , and degree matrix , which is a diagonal matrix, where each diagonal entry of a row , , represents the node degree of node . The Laplacian of the matrix is defined as . Now, a ratio-cut partition for graph is defined as a partition of into disjoint , and , such that cost of is minimized.

In such a scenario, the second smallest eigenvalue () of , yields a lower bound on the optimal cost () of ratio-cut partition with . The eigenvector () corresponding to , called the Fiedler vector, bisects the graph into only two communities based on the sign of the corresponding vector entry. Division into a larger number of communities can be achieved by repeated bisection or by using multiple eigenvectors corresponding to the smallest eigenvalues.[9] The examples in Figures 1,2 illustrate the spectral bisection approach.

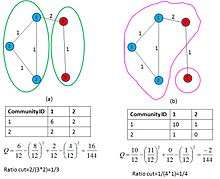

Minimum cut partitioning however fails when the number of communities to be partitioned, or the partition sizes are unknown. For instance, optimizing the cut size for free group sizes puts all vertices in the same community. Additionally, cut size may be the wrong thing to minimize since a good division is not just one with small number of edges between communities. This motivated the use of Modularity (Q) [10] as a metric to optimize a balanced graph partition. The example in Figure 3 illustrates 2 instances of the same graph such that in (a) modularity (Q) is the partitioning metric and in (b), ratio-cut is the partitioning metric.

Another objective function used for graph partitioning is Conductance which is the ratio between the number of cut edges and the volume of the smallest part. Conductance is related to electrical flows and random walks. The Cheeger bound guarantees that spectral bisection provides partitions with nearly optimal conductance. The quality of this approximation depends on the second smallest eigenvalue of the Laplacian λ2.

Other graph partition methods

Spin models have been used for clustering of multivariate data wherein similarities are translated into coupling strengths.[11] The properties of ground state spin configuration can be directly interpreted as communities. Thus, a graph is partitioned to minimize the Hamiltonian of the partitioned graph. The Hamiltonian (H) is derived by assigning the following partition rewards and penalties.

- Reward internal edges between nodes of same group (same spin)

- Penalize missing edges in same group

- Penalize existing edges between different groups

- Reward non-links between different groups.

Additionally, Kernel PCA based Spectral clustering takes a form of least squares Support Vector Machine framework, and hence it becomes possible to project the data entries to a kernel induced feature space that has maximal variance, thus implying a high separation between the projected communities [12]

Some methods express graph partitioning as a multi-criteria optimization problem which can be solved using local methods expressed in a game theoretic framework where each node makes a decision on the partition it chooses.[13]

Software tools

Chaco,[14] due to Hendrickson and Leland, implements the multilevel approach outlined above and basic local search algorithms. Moreover, they implement spectral partitioning techniques.

METIS[7] is a graph partitioning family by Karypis and Kumar. Among this family, kMetis aims at greater partitioning speed, hMetis,[8] applies to hypergraphs and aims at partition quality, and ParMetis[7] is a parallel implementation of the Metis graph partitioning algorithm.

PaToH[15] is another hypergraph partitioner.

Scotch[16] is graph partitioning framework by Pellegrini. It uses recursive multilevel bisection and includes sequential as well as parallel partitioning techniques.

Jostle[17] is a sequential and parallel graph partitioning solver developed by Chris Walshaw. The commercialized version of this partitioner is known as NetWorks.

Party[18] implements the Bubble/shape-optimized framework and the Helpful Sets algorithm.

The software packages DibaP[19] and its MPI-parallel variant PDibaP[20] by Meyerhenke implement the Bubble framework using diffusion; DibaP also uses AMG-based techniques for coarsening and solving linear systems arising in the diffusive approach.

Sanders and Schulz released a graph partitioning package KaHIP[21] (Karlsruhe High Quality Partitioning) that implements for example flow-based methods, more-localized local searches and several parallel and sequential meta-heuristics.

The tools Parkway[22] by Trifunovic and Knottenbelt as well as Zoltan[23] by Devine et al. focus on hypergraph partitioning.

List of free open-source frameworks:

| Name | License | Brief info |

|---|---|---|

| Chaco | GPL | software package implementing spectral techniques and the multilevel approach |

| DiBaP | * | graph partitioning based on multilevel techniques, algebraic multigrid as well as graph based diffusion |

| Jostle | * | multilevel partitioning techniques and diffusive load-balancing, sequential and parallel |

| KaHIP | GPL | several parallel and sequential meta-heuristics, guarantees the balance constraint |

| kMetis | Apache 2.0 | graph partitioning package based on multilevel techniques and k-way local search |

| Mondriaan | LGPL | matrix partitioner to partition rectangular sparse matrices |

| PaToH | BSD | multilevel hypergraph partitioning |

| Parkway | * | parallel multilevel hypergraph partitioning |

| Scotch | CeCILL-C | implements multilevel recursive bisection as well as diffusion techniques, sequential and parallel |

| Zoltan | BSD | hypergraph partitioning |

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Andreev, Konstantin; Räcke, Harald, (2004). "Balanced Graph Partitioning". Proceedings of the sixteenth annual ACM symposium on Parallelism in algorithms and architectures. Barcelona, Spain: 120–124. doi:10.1145/1007912.1007931. ISBN 1-58113-840-7.

- ↑ Buluc, Aydin; Meyerhenke, Henning; Safro, Ilya; Sanders, Peter; Schulz, Christian (2013). Recent Advances in Graph Partitioning. arXiv:1311.3144

.

. - ↑ Feldmann, Andreas Emil; Foschini, Luca (2012). "Balanced Partitions of Trees and Applications". Proceedings of the 29th International Symposium on Theoretical Aspects of Computer Science. Paris, France: 100–111.

- 1 2 Feldmann, Andreas Emil (2012). "Fast Balanced Partitioning is Hard, Even on Grids and Trees". Proceedings of the 37th International Symposium on Mathematical Foundations of Computer Science. Bratislava, Slovakia.

- ↑ Garey, Michael R.; Johnson, David S. (1979). Computers and intractability: A guide to the theory of NP-completeness. W. H. Freeman & Co. ISBN 0-7167-1044-7.

- ↑ Hendrickson, B.; Leland, R. (1995). A multilevel algorithm for partitioning graphs. Proceedings of the 1995 ACM/IEEE conference on Supercomputing. ACM. p. 28.

- 1 2 3 Karypis, G.; Kumar, V. (1999). "A fast and high quality multilevel scheme for partitioning irregular graphs". SIAM Journal on Scientific Computing. 20 (1): 359. doi:10.1137/S1064827595287997.

- 1 2 Karypis, G. and Aggarwal, R. and Kumar, V. and Shekhar, S. (1997). Multilevel hypergraph partitioning: application in VLSI domain. Proceedings of the 34th annual Design Automation Conference. pp. 526–529.

- ↑ M. Naumov; T. Moon (2016). "Parallel Spectral Graph Partitioning". NVIDIA Technical Report. nvr-2016-001.

- ↑ Newman, M. E. J. (2006). "Modularity and community structure in networks". PNAS. 103 (23): 8577–8696. doi:10.1073/pnas.0601602103. PMC 1482622

. PMID 16723398.

. PMID 16723398. - ↑ Reichardt, Jörg; Bornholdt, Stefan (Jul 2006). "Statistical mechanics of community detection". Phys. Rev. E. 74 (1): 016110. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.74.016110.

- ↑ Carlos Alzate; Johan A.K. Suykens (2010). "Multiway Spectral Clustering with Out-of-Sample Extensions through Weighted Kernel PCA". IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence. IEEE Computer Society. 32 (2): 335–347. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2008.292. ISSN 0162-8828. PMID 20075462.

- ↑ Kurve, Griffin, Kesidis (2011) "A graph partitioning game for distributed simulation of networks" Proceedings of the 2011 International Workshop on Modeling, Analysis, and Control of Complex Networks: 9 -16

- ↑ Bruce Hendrickson. "Chaco: Software for Partitioning Graphs".

- ↑ Ü. Catalyürek; C. Aykanat (2011). PaToH: Partitioning Tool for Hypergraphs.

- ↑ C. Chevalier; F. Pellegrini (2008). "PT-Scotch: A Tool for Efficient Parallel Graph Ordering". Parallel Computing. 34 (6): 318–331. doi:10.1016/j.parco.2007.12.001.

- ↑ C. Walshaw; M. Cross (2000). "Mesh Partitioning: A Multilevel Balancing and Refinement Algorithm". Journal on Scientific Computing. 22 (1): 63–80. doi:10.1137/s1064827598337373.

- ↑ R. Diekmann; R. Preis; F. Schlimbach; C. Walshaw (2000). "Shape-optimized Mesh Partitioning and Load Balancing for Parallel Adaptive FEM". Parallel Computing. 26 (12): 1555–1581. doi:10.1016/s0167-8191(00)00043-0.

- ↑ H. Meyerhenke; B. Monien; T. Sauerwald (2008). "A New Diffusion-Based Multilevel Algorithm for Computing Graph Partitions". Journal of Parallel Computing and Distributed Computing. 69 (9): 750–761. doi:10.1016/j.jpdc.2009.04.005.

- ↑ H. Meyerhenke (2013). Shape Optimizing Load Balancing for MPI-Parallel Adaptive Numerical Simulations. 10th DIMACS Implementation Challenge on Graph Partitioning and Graph Clustering. pp. 67–82.

- ↑ P. Sanders and C. Schulz (2011). Engineering Multilevel Graph Partitioning Algorithms. Proceedings of the 19th European Symposium on Algorithms (ESA). 6942. pp. 469–480.

- ↑ A. Trifunovic; W. J. Knottenbelt (2008). "Parallel Multilevel Algorithms for Hypergraph Partitioning". Journal of Parallel and Distributed Computing. 68 (5): 563–581. doi:10.1016/j.jpdc.2007.11.002.

- ↑ K. Devine; E. Boman; R. Heaphy; R. Bisseling; Ü. Catalyurek (2006). Parallel Hypergraph Partitioning for Scientific Computing. Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Parallel and Distributed Processing. pp. 124–124.

External links

- Chamberlain, Bradford L. (1998). "Graph Partitioning Algorithms for Distributing Workloads of Parallel Computations"

Bibliography

- Charles-Edmond Bichot; Patrick Siarry (2011). Graph Partitioning: Optimisation and Applications. ISTE – Wiley. p. 384. ISBN 978-1848212336.

- Feldmann, Andreas Emil (2012). Balanced Partitioning of Grids and Related Graphs: A Theoretical Study of Data Distribution in Parallel Finite Element Model Simulations. Goettingen, Germany: Cuvillier Verlag. p. 218. ISBN 978-3954041251. An exhaustive analysis of the problem from a theoretical point of view.

- BW Kernighan; S Lin (1970). "An Efficient Heuristic Procedure for Partitioning Graphs" (PDF). Bell System Technical Journal. One of the early fundamental works in the field. However, performance is O(n2), so it is no longer commonly used.

- CM Fiduccia; RM Mattheyses (1982). A Linear-Time Heuristic for Improving Network Partitions. Design Automation Conference. A later variant that is linear time, very commonly used, both by itself and as part of multilevel partitioning, see below.

- G Karypis; V Kumar (1999). "A Fast and High Quality Multilevel Scheme for Partitioning Irregular Graphs". Siam Journal on Scientific Computing. Multi-level partitioning is the current state of the art. This paper also has good explanations of many other methods, and comparisons of the various methods on a wide variety of problems.

- Karypis, G., Aggarwal, R., Kumar, V., and Shekhar, S. (March 1999). "Multilevel hypergraph partitioning: applications in VLSI domain". IEEE Transactions on Very Large Scale Integration (VLSI) Systems. 7 (1): 69–79. doi:10.1109/92.748202. Graph partitioning (and in particular, hypergraph partitioning) has many applications to IC design.

- S. Kirkpatrick; C. D. Gelatt Jr.; M. P. Vecchi (13 May 1983). "Optimization by Simulated Annealing". Science. 220 (4598): 671–680. doi:10.1126/science.220.4598.671. PMID 17813860. Simulated annealing can be used as well.

- Hagen, L.; Kahng, A.B. (September 1992). "New spectral methods for ratio cut partitioning and clustering". IEEE Transactions on Computer-Aided Design of Integrated Circuits and Systems. 11, (9): 1074–1085. doi:10.1109/43.159993.. There is a whole class of spectral partitioning methods, which use the Eigenvectors of the Laplacian of the connectivity graph. You can see a demo of this, using Matlab.