Hellenistic influence on Indian art

Hellenistic influence on Indian art reflects the artistic influence of the Greeks on Indian art following the conquests of Alexander the Great, from the end of the 4th century BCE to the first centuries of our era. The Greeks in effect maintained a political presence at the doorstep, and sometimes within India, down to the 1st century CE with the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom and the Indo-Greek Kingdoms, with many noticeable influences on the arts of the Maurya Empire (c.321-185 BCE) especially.[1] Hellenistic influence on Indian art was also felt for several more centuries during the period of Greco-Buddhist art.[1][2]

Historical context

Obv: Alexander being crowned by Nike.

Rev: Alexander attacking king Porus on his elephant.

Silver. British Museum.

The Greek conquests in India under Alexander the Great were limited in time (327-326 BCE) and in extent, but they had extensive long term effects as Greeks settled for centuries at the doorstep of India. Soon after the departure of Alexander, the Greeks (described as Yona or Yavana in Indian sources from the Greek "Ionian") may then have participated, together with other groups, in the armed uprising of Chandragupta Maurya against the Nanda Dynasty around 322 BCE, and gone as far as Pataliputra for the capture of the city from the Nandas. The Mudrarakshasa of Visakhadutta as well as the Jaina work Parisishtaparvan talk of Chandragupta's alliance with the Himalayan king Parvatka, often identified with Porus.[3] According to these accounts, this alliance gave Chandragupta a composite and powerful army made up of Yavanas (Greeks), Kambojas, Shakas (Scythians), Kiratas (Nepalese), Parasikas (Persians) and Bahlikas (Bactrians) who took Pataliputra.[4][5][6]

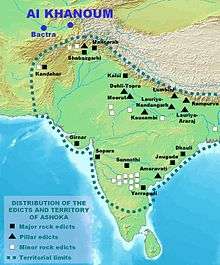

After these events, the Greeks were able to maintain a structured presence at the door of India for about three centuries, through the Seleucid Empire and the Greco-Bactrian kingdom, down to the time of the Indo-Greek kingdoms, which ended sometimes in the 1st century CE. During that time, the city of Ai-Khanoum, capital of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom, and the capitals of the Indo-Greek Kingdom, the cities of Sirkap, founded in what is now Pakistan on the Greek Hippodamian grid plan, and Sagala, now located in Pakistan 10km from the border with India, interacted heavily with the Indian subcontinent. It is considered that Ai-Khanoum and Sirkap may have been primary actors in transmitting Western artistic influence to India, for example in the creation of the quasi-Ionic Pataliputra capital or the floral friezes of the Pillars of Ashoka.[7] Numerous Greek ambassadors, such as Megasthenes, Deimachus and Dionysius, stayed at the Mauryan court in Pataliputra.

The scope of adoption goes from designs such as the bead and reel pattern, the central flame palmette design and a variety of other moldings, to the lifelike rendering of animal sculpture and the design and function of the Ionic anta capital in the palace of Pataliputra.[8] After the 1st century CE, Hellenistic influence continued to be perceived in the syncretic Greco-Buddhist art of Gandhara, down to the 4th-5th century CE. Arguably, Hellenistic influence continued to be felt indirectly in India arts for many centuries thereafter.

Influence on Indian monumental stone architecture (268-180 BCE)

During the Maurya period (c.321-185 BCE), and especially during the time of Emperor Ashoka (c.268 to 232 BCE), Hellenistic influence seems to have played a role in the establishment of Indian monumental stone architecture. Excavations in the ancient palace of Pataliputra have brought to light Hellenistic sculptural works, and Hellenistic influence appear in the Pillars of Ashoka at about the same period.

Extent of relations

Numerous contacts have been recorded between the Maurya Empire and the Greek realm. Seleucus I Nicator attempted to conquer India in 305 BCE, but he finally came to an agreement with Chandragupta Maurya, and signed a treaty which, according to Strabo, ceded a number of territories to Chandragupta, including large parts of what is now Afghanistan and Pakistan. A "marital agreement" was also concluded, and Seleucus received five hundred war elephants, a military asset which would play a decisive role at the Battle of Ipsus in 301 BCE.[9][10]

Later, numerous ambassadors visited the Indian court in Pataliputra, especially Megasthenes to Chandragupta, later Deimakos to his son Bindusara, and later again Ptolemy II Philadelphus, the ruler of Ptolemaic Egypt and contemporary of Ashoka, is also recorded by Pliny the Elder as having sent an ambassador named Dionysius to the Mauryan court.[11] Ashoka made communications with Greek populations on the site of Alexandria Arachosia (Old Kandahar), using the Kandahar Bilingual Rock Inscription or the Kandahar Greek Inscription.

The Greco-Bactrian Kingdom with its capital of Ai-Khanoum maintained a strong Hellenistic presence at the doorstep of India from 280 to 140 BCE, and after that date went into India itself to form Indo-Greek kingdoms which would last until the 1st century CE. At the same time, Ashoka wrote some of his edicts in Greek, and claimed to have sent ambassadors to Greek rulers as far as the Mediterranean, suggesting his willingness to communicate with the Hellenistic realm.

Instances of Hellenistic influence

During that period, several instance of artistic influence are known, particular in the area of monumental stone sculpture and statuary, an area with no known precedents in India. The main period of stone architectural creation seems to correspond to the period of Ashoka's reign (c.?268 to 232 BCE).[12] Before that, Indians may have had a tradition of wooden architecture, but no remains have ever been found to prove that point. However remains of wooden palisades were discovered at archaeological sites in Pataliputra, confirmed Classical accounts that the city had such wooden ramparts. The first examples of stone architecture were also found in the palace compound of Pataliputra, with the distinctly Hellenistic Pataliputra capital and a pillared hall using polished-stone columns. The other remarkable example of monumental stone architecture is that of the Pillars of Ashoka, themselves displaying no little Hellenistic influence.[13] Overall, according to Boardman, "the visual experience of many Ashokan and later city dwellers in India was considerably conditioned by foreign arts, translated to an Indian environment, just as the archaic Greek had been by the Syrian, the Roman by the Greek, and the Persian by the art of their whole empire".[14]

Pataliputra capital (3rd century BCE)

The Pataliputra capital is a monumental rectangular capital with volutes and Classical designs, that was discovered in the palace ruins of the ancient Mauryan Empire capital city of Pataliputra (modern Patna, northeastern India). It is dated to the 3rd century BCE. It is, together with the Pillars of Ashoka one of the first known examples of Indian stone architecture, as no Indian stone monuments or sculptures are known from before that period.[1] It is also one of the first archaeological clues suggesting Hellenistic influence on the arts of India, in this case sculptural palatial art. The Archaeological Survey of India, an Indian government agency attached to the Ministry of Culture that is responsible for archaeological research and the conservation and preservation of cultural monument in India, straightforwardly describes it as "a colossal capital in the Hellenistic style".[15]

Although this capital was a major piece of architecture in the Mauryan palace of Pataliputra, since most of Pataliputra was not excavated, and remains hidden under the modern city of Patna, it is impossible to know the exact nature or extent of the monuments or the buildings that incorporated it.

One capital from Sarnath is known, which seems to be an adaptation of the design of the Pataliputra capital. This other capital is also said to be from the Mauryan period. It is, together with the Pataliputra capital, considered as "a stone braket suggestive of the Ionic order".[16] A later capital found in Mathura dating to the 2nd or 3rd century (Kushan period) displays a central palmette with side volutes in a style described as "Ionic", in the same kind of composition as the Pataliputra capital but with a coarser rendering. (photograph).[17]

Pillars of Ashoka (3rd century BCE)

The Pillars of Ashoka were built during the reign of the Maurya Empire Ashoka circa 250 BCE. They were new attempts as mastering stone architecture, as no Indian stone monuments or sculptures are known from before that period.[1]

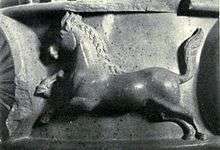

There are altogether seven remaining capitals, five with lions, one with an elephant and one with a zebu bull. One of them, the four lions of Sarnath, has become the State Emblem of India. The animal capitals are composed of a lotiform base, with an abacus decorated with floral, symbolic or animal designs, topped by the realistic depiction of an animal, thought to each represent a traditional direction in India.

Various foreign influences have been described in the design of these capitals.[18] Placing animals on top of a lotiform capital reminds of Achaemenid columns. The animals, especially the horse on the Sarnath Lion Capital of Ashoka or the bull of the Rampurva capital are said to be typically Greek in realism, and belong to a type of highly realistic treatment which cannot be found in Persia.[1] The abacus parts also often seem to display a strong influence of Greek art: in the case of the Rampurva bull or the Sankassa elephant, it is composed of flame palmettes alternated with stylized lotuses and small rosettes flowers.[19] A similar kind of design can be seen in the frieze of the lost capital of the Allahabad pillar. These designs likely originated in Greek and Near-Eastern arts.[20][1] They would probably have come from the neighboring Seleucid Empire, and specifically from a Hellenistic city such as Ai-Khanoum, located at the doorstep of India.[21]

Decorative moldings and sculptures

Flame palmette

The flame palmette, central decorative element of the Pataliputra pillar is considered as a purely Greek motif. The first appearance of "flame palmettes" goes back the stand-alone floral akroteria of the Parthenon (447-432 BCE),[23] and slightly later at the Temple of Athena Nike.[24] Flame palmettes were then introduced into friezes of floral motifs in replacement of the regular palmette. Flame palmettes are used extensively in India floral friezes, starting with the floral friezes on the capitals of the pillar of Ashoka. A monumental flame palmette can be seen on the top of the Sunga gateway at Bharhut (2nd century BCE).

Botanical combinations

According to Boardman, although lotus friezes or palmette friezes were known in Mesopotamia centuries before, the unnatural combination of various botanical elements which have no relationship in the wild, such as the palmette, the lotus and sometimes rosette flowers, is a purely Greek innovation, which was then adopted on a very broad geographical scale.[25]

Bead and reel

According to art historian John Boardman, the bead and reels motif was entirely developed in Greece from motifs derived from the turning techniques used for wood and metal, and was first employed in stone sculpture in Greece during the 6th century BCE. The motif then spread to Persia, Egypt and the Hellenistic world, and as far as India, where it can be found on the abacus part of some of the Pillars of Ashoka or the Pataliputra capital.[26]

Influence on monumental statuary

Hellenistic arts may have been influential in early statuary (Mauryan and Sunga periods). A few monumental Yakshas are considered as the earliest free-standing statues in India .[27] The treatment of the dress especially, with lines of geometric folds, is considered as a Hellenistic innovation. There are no known previous example of such statuary in India, and they closely resemble Greek Late Archaic mannerism which could have been transmitted to India through Achaemenid Persia.[28] This motif appears again in the Sunga works of Bharhut, especially on a depiction of on a foreign soldier, but the same treatment of the dress is also visible on purely Indian figures.

First visual representations of Indian deities

One of the last Greco-Bactrian kings, Agathocles of Bactria (ruled 190-180 BCE), issued remarkable Indian-standard square coins bearing the first known representations of Indian deities, which have been variously interpreted as Vishnu, Shiva, Vasudeva, Buddha or Balarama. Altogether, six such Indian-standard silver drachmas in the name of Agathocles were discovered at Ai-Khanoum in 1970.[29][30][31] Some other coins by Agathocles are also thought to represent the Buddhist lion and the Indian goddess Lakshmi.[32] The Indian coinage of Agathocles is few but spectacular. These coins at least demonstrate the readiness of Greek kings to represent deities of foreign origin. The dedication of a Greek envoy to the cult of Garuda at the Heliodorus pillar in Besnagar could also be indicative of some level of religious syncretism.

Direct influence in Northwestern India (180 BCE-20CE)

The Indo-Greek period (180 BCE-20CE) marks a time when Bactrian Greeks established themselves directly in the northwestern parts of the Indian subcontinent following the fall of the Maurya Empire and its takeover by the Sunga.

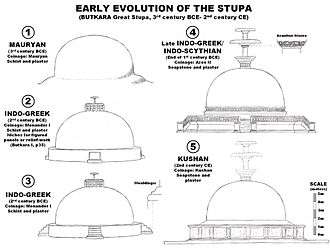

Religious buildings

Indo-Greek territories seems to have been highly involved with Buddhist. Numerous stupas, which had been set up during the time of Ashoka, were then reinforced and embellished during the Indo-Greek period, using elements of Hellenistic sculpture. A detailed archaeological analysis was made especially at the Butkara stupa which allowed to define precisely what had been made during the Indo-Greek period, and what came later. The Indo-Greeks are known for the additions and niches, stairs and balustrades in Hellenistic architectural style. These efforts would then continue during the Indo-Scythian and Kushan periods.[33]

Depiction of the Buddha in human form

Numerous Greek artifacts were found in the city of Sirkap, near Taxila in modern Pakistan and in Sagala, a city in modern Pakistan 10km from the border with India. Sirkap was founded as a capital of the Indo-Greek Kingdom and was laid-out on the Greek Hippodamian city plan; Sagala was also a Indo-Greek capital. Individuals in Greek dress are can be identified on numerous friezes.

.jpeg)

Although there is still some debate, the first anthropomorphic representations of the Buddha himself are often considered a result of the Greco-Buddhist interaction. Before this innovation, Buddhist art was aniconic, or very largely so: the Buddha was only represented through his symbols (an empty throne, the Bodhi Tree, Buddha footprints, the Dharmachakra).[34]

Probably not feeling bound by these restrictions, and because of "their cult of form, the Greeks were the first to attempt a sculptural representation of the Buddha".[35] In many parts of the Ancient World, the Greeks did develop syncretic divinities, that could become a common religious focus for populations with different traditions: a well-known example is Serapis, introduced by Ptolemy I Soter in Egypt, who combined aspects of Greek and Egyptian Gods. In India as well, it was only natural for the Greeks to create a single common divinity by combining the image of a Greek god-king (Apollo, with the traditional physical characteristics of the Buddha).

Some authors have argued that the Greek sculptural treatment of the dress has been adopted for the Buddha and Bodhisattvas throughout India. It is, even today, a hallmark of numerous Buddhist sculptures as far as China and Japan.[36]

Coinage

Indo-Greek coinage is rich and varied, and contains some of the best coins of antiquity. Its influence on Indian coinage was far-reaching. The Greek script became used extensively on coins for many centuries, as was the habit of depicting a ruler on the obverse, often in profile, and deities on the reverse. The Western Satrap, a western dynasty of foreign origin adopted Indo-Greek designs. The Kushans (1st to 4th century CE) used the Greek script and Greek deities on their coinage. Even as late as the Gupta Empire (4th to 6th century CE), Kumaragupta I issued coins with an imitation of Greek script.

-

Coin of the Audumbaras influenced by Indo-Greek coin styles. 2nd century BCE

-

Coin of the Kunindas influenced by Indo-Greek coin styles. 2nd century BCE

-

Coin of Gupta Chandragupta II with pseudo-Greek legend in the obverse. 4th century CE

Greco-Buddhist artistic legacy (1st century BCE-4 th century CE)

The full bloom of Greco-Buddhist art seems to have postdated the Indo-Greek Kingdom, although it has been suggested that individual Greek artisans and artist probably continued to work for the new masters. It is apparently during the rule of the Indo-Scythian, the Indo-Parthian and Kushan that Greco-Buddhist art evolved to become a dominant art form in the northwest of the Indian Subcontinent. Whereas other areas of India, especially the area of Mathura received the influence of the Greco-Buddhist school remains a matter of debate.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 A Brief History of India, Alain Daniélou, Inner Traditions / Bear & Co, 2003, p.89-91

- ↑ History of Civilizations of Central Asia: The development of sedentary and nomadic civilizations: 700 B.C. to A.D. 250, Ahmad Hasan Dani, Motilal Banarsidass Publ., 1999, Paul Bernard, p.128 and sig.

- ↑ Chandragupta Maurya and His Times, Radhakumud Mookerji, Motilal Banarsidass Publ., 1966, p.26-27

- ↑ Chandragupta Maurya and His Times, Radhakumud Mookerji, Motilal Banarsidass Publ., 1966, p.27

- ↑ History Of The Chamar Dynasty, Raj Kumar, Gyan Publishing House, 2008, p.51

- ↑ "Kusumapura was besieged from every direction by the forces of Parvata and Chandragupta: Shakas, Yavanas, Kiratas, Kambojas, Parasikas, Bahlikas and others, assembled on the advice of Chanakya" in Mudrarakshasa 2. Sanskrit original: "asti tava Shaka-Yavana-Kirata-Kamboja-Parasika-Bahlika parbhutibhih Chankyamatipragrahittaishcha Chandergupta Parvateshvara balairudidhibhiriva parchalitsalilaih samantaad uprudham Kusumpurama". From the French translation, in "Le Ministre et la marque de l'anneau", ISBN 2-7475-5135-0

- ↑ John Boardman, "The Origins of Indian Stone Architecture", p.15

- ↑ John Boardman, "The Origins of Indian Stone Architecture", p.13-22

- ↑ With Arrow, Sword, and Spear: A History of Warfare in the Ancient World, Alfred S. Bradford, Pamela M. Bradford Greenwood Publishing Group, 2001, p.125

- ↑ Ancient Ethnography: New Approaches, Eran Almagor, Joseph Skinner, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2013, p.104

- ↑ "Pliny the Elder, The Natural History (eds. John Bostock, M.D., F.R.S., H.T. Riley, Esq., B.A.)".

- ↑ The origins of Indian Stone Architecture, John Boardman, p.14

- ↑ The origins of Indian Stone Architecture, John Boardman

- ↑ The Origins of Indian Stone Architecture, John Boardman, p.21

- ↑ Archaeological Survey of India report

- ↑ "The Archaeology of Early Historic South Asia: The Emergence of Cities and States"F. R. Allchin, George Erdosy, Cambridge University Press, 1995, listed in page xi

- ↑ The Arts of India, Southeast Asia, and the Himalayas at the Dallas Museum of Art, Published on Dec 12, 2013. Article with photograph

- ↑ The pillars "owe something to the pervasive influence of Achaemenid architecture and sculpture, with no little Greek architectural ornament and sculptural style as well. Notice the florals on the bull capital from Rampurva, and the style of the horse of the Sarnath capital, now the emblem of the Republic of India." "The Diffusion of Classical Art in Antiquity" by John Boardman, Princeton University Press, 1993, p.110

- ↑ "Buddhist Architecture" by Huu Phuoc Le, Grafikol, 2010, p.40

- ↑ "Buddhist Architecture" by Huu Phuoc Le, Grafikol, 2010, p.44

- ↑ "Reflections on The origins of Indian Stone Architecture", John Boardman, p.15

- ↑ The origin of Indian Stone Architecture, John Boardman, p.16

- ↑ NEW FRAGMENTI'S OF THE PARTHENON ACROTERIA, The American School of Classical Studies at Athens

- ↑ The Sanctuary of Athena Nike in Athens: Architectural Stages and Chronology, Ira S. Mark, ASCSA, 1993, p.83

- ↑ The Origins of Indian Stone Archtitecture, John Boardman, p.16

- ↑ John Boardman, "The Origins of Indian Stone Architecture", p.16 and others

- ↑ John Boardman, "The Diffusion of Classical Art in Antiquity", Princeton University Press, 1993, p.112

- ↑ "It has no local antecedents and looks most like a Greek Late Archaic mannerism" (John Boardman, "The Diffusion of Classical Art in Antiquity", Princeton University Press, 1993, p.112.)

- ↑ Alexander the Great and Bactria: The Formation of a Greek Frontier in Central Asia, Frank Lee Holt, Brill Archive, 1988, p.2

- ↑ Iconography of Balarāma, Nilakanth Purushottam Joshi, Abhinav Publications, 1979, p.22

- ↑ The Hellenistic World: Using Coins as Sources, Peter Thonemann, Cambridge University Press, 2016, p.101

- ↑ The Hellenistic World: Using Coins as Sources, Peter Thonemann, Cambridge University Press, 2016, p.101

- ↑ "De l'Indus a l'Oxus: archaeologie de l'Asie Centrale", Pierfrancesco Callieri, p212: "The diffusion, from the second century BCE, of Hellenistic influences in the architecture of Swat is also attested by the archaeological searches at the sanctuary of Butkara I, which saw its stupa "monumentalized" at that exact time by basal elements and decorative alcoves derived from Hellenistic architecture".

- ↑ South Asian Buddhism: A Survey, Stephen C. Berkwitz Routledge, 2012, p.29 et sig.

- ↑ Linssen, "Zen Living"

- ↑ John Boardman, "The Diffusion of Classical Art in Antiquity", Princeton University Press, 1993, p.112