History of Belgian Limburg

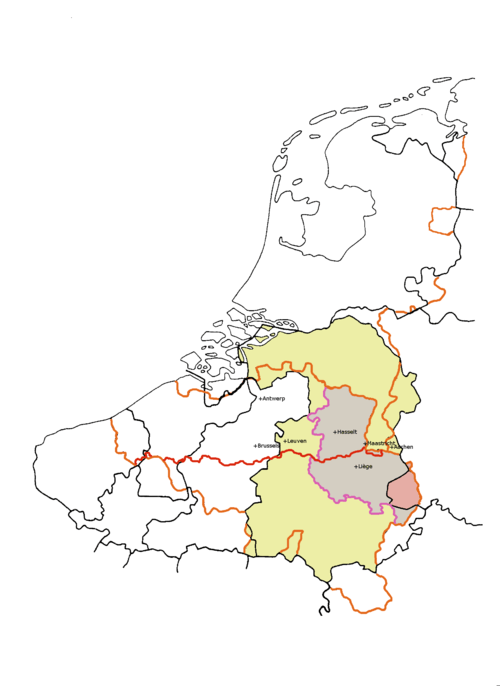

The Belgian province of Limburg in Flanders (Dutch speaking Belgium) is a region which has had many names and border changes over its long recorded history. Its modern name is a name shared with the neighbouring province of the Netherlands, with which it was for a while politically united (under French and then Dutch rule from 1794 until 1839). And in turn both of these provinces received their modern name only in the 19th century, based upon the name of the medieval Duchy of Limburg which was actually based in neighbouring Wallonia, in the town of Limbourg on the Vesdre.

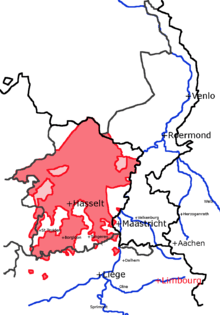

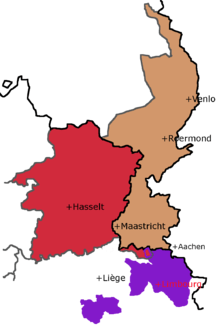

For much of its recorded history, most of what is now called Belgian Limburg was known as Loon (French Looz). Loon was a medieval county, and when the line of the Counts died the area became part of the Prince-Bishopric of Liège but was still often referred to as the "land of Loon" (land van Loon in Dutch). The original capital of medieval Loon is today officially called Borgloon, and the capital of the province is now Hasselt.

In Roman times, Belgian Limburg, and probably also at least parts of the Dutch province and the medieval Duchy, were in the Civitas Tungrorum, which had its capital in Tongeren.

Prehistoric

Belgian Limburg in the ice ages is assumed, like neighbouring areas of Europe, to have been home to dispersed populations of nomadic hunter gatherers including Neanderthals and later waves of "Anatomically modern humans". Upper and middle paleolithic finds in Limburg are not common compared to findings to the south in the Wallonian province of Liège. In the upper paleolithic archaeological finds also become more common in Limburg. In general terms, the area was part of the broadly defined cultural group known as the Magdalenian (17,000 BP to 9,000 BP), and then the Azilian. The particular type of Azilian was known as the Tjongerian, which is in turn part of the Federmesser group of Azilian cultures.[1] Tjongerian finds have been made in Lommel, Zolder, and Zonhoven, on the southern edge of the sandy Campine lowlands in the north of the province.[2]

In the younger Dryas, Limburg was inhabited first by the Ahrensburg culture, evidence of which has been found in Zonhoven.[3] Later, the Tardenoisian culture was shared with all neighbouring areas (Brabant, the Netherlands, and Wallonia). It apparently arrived from France. One such site is in Ruiterskuil in Opglabbeek.[3]

The Neolithic begins with the first farmers in the area who belonged to the LBK culture, arriving around 5000 BCE from the east,[4] and remaining mainly in the south of Belgian Limburg, especially the southeastern corner of the province, between Tongeren and Maastricht. The sandy northern Campine lowlands were clearly not successful for them. Finds in neighbouring Dutch Limburg and Wallonia are more widely distributed. This was one of the westernmost colonizations of this first wave of farmers, and also a point of contact between farming and local non-farming cultures.[5] So called Limburg pottery is a particular style associated with this western LBK culture, which is also associated with La Hoguette pottery and stretches into northern France. It has sometimes been argued that these technologies are the result of pottery technology spreading beyond the original LBK farming population, and being made by hunter gatherers.[6] Another remarkable aspect of this version of the LBK culture is that some settlements show signs of being fortified, implying the threat of violence. The sandy north of Limburg appears to have become a contact area for hunger gatherers of the Swifterbant culture, who traded with the farmers.[5][7]

The LBK culture appears to have disappeared from the area around 4000 BCE. Around 500 years later, in a second phase of the Neolithic of the area, the Michelsberg culture appeared in the region. It was a relatively less sedentary culture, which once again showed signs of concerns with fortification. A similar Michelsberg culture appeared in the Rhineland of Germany, and it also appears to be related to the Chasséen culture in northern France. But the Michelsberg in Belgium had distinct local features. If it developed locally, local hunters and gatherers may have played a role, but archaeological evidence is so far inconclusive about what happened.[5][7] This culture was apparently able to spread into the Campine, or at least influence it more. During this period, there are stronger signs that the hunter-gatherer Swifterbant cultures of these areas were becoming involved in pottery and farming themselves.

In the third and late fourth millennia BCE, the whole of Flanders shows relatively little evidence of human habitation. Although it is felt that there was a continuing human presence, the types of evidence available make judgement about the details very difficult.[8] To the south of Belgian Limburg, the Seine-Oise-Marne culture spread into the nearby Ardennes, and is associated with megalithic sites there. To the north and east, in the Netherlands, a semi-sedentary culture group has been proposed to have existed, the so-called Vlaardingen-Wartburg-Stein complex, which possibly developed from the above-mentioned Swifterbant and Michelsburg cultures.[9] The same pattern continues into the late Neolithic and early Bronze Age. In the last part of the Neolithic, evidence is found for the Corded Ware and Bell Beaker cultures in neighboring Dutch Limburg, but much less in Belgian Limburg. During the early and middle Bronze age, Belgian Limburg is often considered to have been in the zone where the Hilversum culture lived, but finds are not in Belgian Limburg itself. This was a culture found in the southern and central Netherlands, and the Belgian coast, and is considered to be related to the contemporary Wessex culture of southern England.[10]

During the late Bronze age, Belgian Limburg received immigrants belonging to the Urnfield culture. These cremation practicing farmers caused a population increase which included the sandy north of Limburg, where pastoralism was also practiced. It is possible that these people brought the first Indo-European languages to Belgium. As in other areas of Europe where this culture arrived, the Urnfield culture was following by the Iron age Halstatt and La Tène cultures, both associated with Celtic languages and culture. It has been suggested that the original Urnfield population of the area stayed, and that the Halstatt and La Tène cultures were the result of new elites moving in, with new dialects of early Indo-European. Rich La Tène urn burials have been found in Eigenbilzen (Bilzen) in Haspengouw and Wijshagen (Meeuwen-Gruitrode) in the Kempen.[11][12][13] It is likely that the various peoples and languages that the Romans found in the region arrived during the Bronze and Iron Ages. The Eburones who were in this area when Caesar conquered it, are associated by archaeologists with a material culture which has its roots in local variations of the Urnfield culture. It is during the late Iron Age that there is archaeological evidence for the development of a "Celtic field" system in the less fertile Campine, and increasingly social stratification and centralization, even though the area remained relatively un-developed compared to other nearby parts of Europe.[14]

Compared to surrounding areas of Europe, one remarkable thing about this pre-Roman period is the lack of hill forts, a pattern throughout all of Flanders. Only one is known in Limburg, at Caster or Castaert in Riemst, right in the southeastern corner of Limburg. In the rest of Flanders only one more is known, at Asse.[15][16]

The "Germani" and the "Belgae"

The only surviving written source of information which is specifically about Belgian Limburg before it became part of the Roman empire is Julius Caesar, who left a famous Commentary of his wars in the region, which were part of his Gallic campaign. In this period, this whole area, together with other areas towards the Ardennes in the south, and the Rhine to the north and east, was the homeland of one large tribal grouping known as the Germani cisrhenani, as well as a distinct tribe known as the Aduatuci.

The Germani cisrhenani tribes which Caesar named where the Eburones, the Condrusi, the Paemani (or Caemani), the Caeroesi, and the Segni.[17][18] The biggest and most important tribe were the Eburones, and it is they who appear to have dominated all or most of modern-day Belgian Limburg, with a territory probably stretching into the flat Campine (Dutch Kempen) northern part of this region, and also stretching into neighbouring regions of the Netherlands and Germany. The other tribes are thought to have lived further south, in what is today Wallonia, or else just over the border in Germany.

The term Germani for these Belgic tribes requires explanation in order to avoid confusion. Caesar also referred to other tribes living over the east of the Rhine as Germani, and he called that region Germania, the source of the modern word Germany. He may have been the first to extend the term in this way, apparently because he was told that this is where such people came from. (Something archaeologists have not been able to confirm.) So he distinguished the Germani in the Belgic area as "Germani cisrhenani", and treated the other "Germani" as the ones living in their real homeland. Confusingly, Caesar also treated the Germani cisrhenani as Belgic Gauls, a type of people he contrasted with the Germani, and his reports suggest that they also treated themselves this way. In fact he said that not only the Germani cisrhenani, but the biggest part of the Belgae where descended from Germani from over the Rhine, so possibly he saw other northern Belgic tribes such as the neighbouring Nervii as Germani cisrhenani in a broad "racial" sense. And Tacitus, some generations after Caesar, says that the Nervii of his time still claimed such a link (see below).

Concerning the question of when this supposed immigration from across the Rhine happened, it was at least some generations before Caesar. He reports that the Germani cisrhenani in the Limburg region were the only people in Gaul who had defended themselves successfully from the migrations of the Cimbri and Teutones in the second century BCE. The Aduatuci on the other hand, were descendants of those Cimbri who had been allowed to settle in a particular area within the region. So in effect Caesar used the term two different ways, and it is likely that the original narrow meaning of the word was specific to the people living in and around modern Limburg, in the later Roman Civitas Tungrorum.[17]

Whether or not any of the Belgian Germani, or indeed the Aduatuci, spoke a Germanic language is uncertain. The names of their leaders and their tribes for the most part appear to have Celtic origins, which is in fact also true of the neighbouring tribes across the Rhine in "Germania" at that time, such the Tencteri and Usipetes. On the other hand, it has been argued by Maurits Gysseling and others that placename analysis shows that a Germanic language was being spoken in this region by the 2nd century BCE, and there are also signs of an older substrate language in the Belgic region. (See Nordwestblock.) So Celtic, while influential culturally, may never have been the main language of the area.[19]

The Aduatuci and the Germani cisrhenani participated in an alliance of Belgic tribes against Caesar in 57 BCE, which was defeated at the Battle of the Sabis. Before that battle, information from the Remi, a tribe allied with Rome, stated that the Germani (the Condrusi, the Eburones, the Caeraesi, and the Paemani; but apparently not the Segni) had collectively promised, they thought, about 40,000 men. The Aduatuci had promised 19,000.[17] This alliance was defeated after a series of events culminating in the Battle of the Sabis.

In 54 BCE, the Eburones and the Aduatuci rebelled again in alliance with the Gaulish tribes to their south and west, the Treveri and Nervii. Also concerning these powerful tribes it is difficult to be certain what language they spoke, although the Treveri are generally thought to have spoken a Celtic language. (Tacitus says of these two tribes that they were not originally Germani, but that they wished to be associated with that name and not the softer name of the Gauls.[20])

The capital of the Eburones is named by Caesar as Aduatuca, and the capital of the region in later Roman times was Aduatuca Tungrorum (modern Tongeren). It is possible that these were the same place, except that the term "Aduatuca" may simply mean "fortification". One reason for doubt is that Caesar seems to indicate that Aduatuca was near the centre of the Eburone territory, and that the main part of this territory lay between the Meuse (Dutch Maas) and the Rhine, while Belgian Limburg lies entirely to the west of the Maas.[18][21]

Apart from the Eburones, the Aduatuci may have lived in Belgian Limburg. Because they had a fort on large hill, and their name may even mean "fort people" it is thought that the Aduatuci lived in hilly Wallonia, but they may also have lived in southeastern Limburg, which is moderately hilly. Ambiorix, one of the two kings of the Eburones, complained to Caesar that he had to pay tribute to the Aduatuci, and that his own son and nephew were kept as captive slaves by them.[22] But once in revolt against the Romans, he rode first to the Aduatuci, and then to the Nervii, seeking their alliance.[23]

After some initial success, the revolt against Caesar failed, and he conquered the area. He states that he tried to annihilate "the race and name of the state of the Eburones", for their "crime" which triggered the revolt, of having killed his lieutenants Quintus Titurius Sabinus and Lucius Aurunculeius Cotta when they demanded to be quartered amongst them for winter.[24] Ambiorix escaped into the Ardennes, with some horse.[25] Many others escaped towards the forests, morasses, and tidal islands of the coast.[24] Caesar decided not to risk men in trying to pursue the rebels into such difficult countryside, and instead tried to encourage other tribes to pillage the area - a plan which back-fired when the Sicambri crossed the Rhine and decided the Roman baggage would be a much richer target than any refugees.

The other king of the Eburones, Cativolcus, killed himself "with the juice of the yew-tree, of which there is a great abundance in Gaul and Germany".[26] The name "Eburones" (like other similar Celtic-based tribal names around Europe) is based on the Celtic word for the yew tree.

Roman empire

Belgian Limburg in Roman times formed the central part of the large district of Civitas Tungrorum, with its capital in modern Tongeren. This district took its name from a new tribal name, the Tungri. However, according to Tacitus, writing some generations after Caesar, this tribe had originally been the first to be called the Germani, and had started using a new name, while many other tribes are started to be called Germani. This would indicate that they were the same group of tribes which had included the Eburones.[20] On the other hand, it is known that during this period, the Romans settled numerous people from across the Rhine, and these may also have made up a significant part of the ancestry of the Tungri.

Under the Romans, the Tungri civitas was first a part of Gallia Belgica, and later split out, unlike their western Belgian neighbours the Menapii and Nervii, to join with the territories which lay along the militarized Rhine border to become part of Germania Inferior "Lower Germania", and still later this was reorganized to become Germania Secunda.[27] Many of the tribal groups which inhabited the west bank of the Rhine were dominated by immigrants from the east bank. To the north of the Tungri, in the Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta in the modern Netherlands were the Batavians and Frisiavones and possibly still some of the Menapii who had been there in Caesar's time. To the northeast, in the bend of the Rhine, were the Cugerni, who were probably descended from a division of the Sicambri, and probably the Baetasi also. To the east of the Tungri were the Sunici and on the Rhine the Ubii, whose city was Cologne, the provincial capital. The Tungri, along with many of the tribal states of Germania Inferior, participated in the Revolt of the Batavi.[28]

Tongeren was a major town on several notable east-west Roman routes including Amiens-Bavay-Tongeren-Maastricht-Heerlen-Cologne, which was a very important route, and Boulogne-Kortrijk-Tienen-Tongeren, which ran just to the south of the modern main road running Tienen-St Truiden-Borgloon-Tongeren, through the villages of Overhespen, Helshoven, and Bommershoven. The more fertile areas south of these roads were more heavily populated and more fully Romanized. In the sandy north of Belgian Limburg, the Romanized population thinned out dramatically in late Roman times, under pressure from constant plundering from Germanic tribes over the Rhine.

Within the civitas Tungrorum, some information survives about sub-districts (pagi), each with apparent tribal names. Most of this information comes from military records, concerning units recruited from such areas. Two of the Germani tribal groups which survived from Caesar's time are that of the Condrusi, who lived in the Condroz of Wallonia, and the Caerosi who lived in the Eifel forest just over the border in modern Germany. But the only surviving name pagus which can be clearly associated with areas in and around Belgian Limburg in that of Toxandria, the district of the Toxandri, which appears to have been a large part of the civitas containing all or most of the sandy Campine region in the north. This is not one of the tribe names Caesar mentions, but some have suggested could be a Latin translation of the name Eburones, both apparently referring to Yew (Latin taxus).[29] Others propose that this group were mainly made up of immigrants from east of the Rhine. It has also been proposed that the Baetasi might have lived near Geetbets, on the Brabant-Limburg border, but it seems more likely that they lived in an area closer to the Rhine in modern Germany.

Two other pagi which appear in records for the first time under the empire, and which may have been in the civitas, are the pagus Vellaus, apparently corresponding to the forest of Veluwe in the Netherlands, and the pagus Catualinus, apparently in or near Heel on the Meuse, which corresponds with Catvalium in the Tabula Peutingeriana map.

Franks

In late Roman and early medieval times, the northern or "Kempen" part of Belgian Limburg once again became very distinct from the southern part. It became virtually empty because of Germanic plundering, and was then settled and ruled by Salian Franks coming over the Rhine and Maas from the north, apparently from the eastern Netherlands (which was itself under pressure from Saxons). These were amongst the first Germanic tribes to become strongly established within the Roman empire, and the ancestors of the Merovingians. They took up an older name of one of the districts of the civitas, "Toxandria", even though the original Toxandri may not have lived there any more. The southern or "Haspengouw" part of Belgian Limburg remained more heavily Romanised, but eventually also became a core land of the Franks. The two east-west Roman routes through Tongeren, mentioned above, became a front line of defense for a while, and are sometimes referred to as the Limes Belgicus. Gregory of Tours reports that it was from the area of Toxandria bordering Tongeren that Chlodio, in the 5th century, launched the Franks into military campaigns of conquest in northern Gaul, soon to become France or "Francia", the country of the Franks.

In Merovingian times, Belgian Limburg was part of Austrasia, and in particular it appears that parts of the Haspengouw were under the control of the Pippinid family, and later their Carolingian descendants. This family were "mayors" of the Merovingian court until they eventually took over rule more openly, when Pepin the short became the first King of the Franks in 752. The founder of the Pippinids was Pepin of Landen, and was probably born in Landen in Belgian Limburg.

Under the Franks, the region begins to be referred to with new placenames, which last into the Middle Ages and in some cases into modern times. A gouw or gau was a Frankish administrative region, translated into Latin as pagus, and roughly corresponding to English "county" or "shire". The ruler of a gouw, if it had one ruler, was typically a count or graaf, but some of the larger gouws came to be divided into smaller counties. Toxandria, in the Kempen, remained one such region. The eastern part of Belgian Limburg, bordering the river Maas or Meuse, was sometimes referred to as the "Maasgau" or Maasau. The southern part, received its modern name of Haspengouw, found in forms such as Haspinga, pagus Hasbaniensis or Hasbania, in old documents such as the Treaty of Meersen, but it was divided into four counties, which the treaty does not name. There were counts of Hesbaye in Carolingian times, but their exact territories are not known with certainty.

By the 9th century, the Frankish Carolingian empire eventually included not only the region of Belgium and northern France, but also eventually much of Western Europe. After the death of Charlemagne, Limburg was part of the Lotharingian division of frankish Europe which lay between France and Germany and stretched to Italy. After the death of its first ruler, Lothar, it was only slowly integrated into Eastern Francia, which was to become the Holy Roman empire. In the period around 881 and 882 the areas along the Maas and in the Haspengouw were plundered by Norse Vikings, who established a base at Asselt on the Maas, today in Roermond in Dutch Limburg. The emperor Charles the Fat tried to negotiate with them. In 1891, the Vikings were back fought several times with forces of Arnulf of Carinthia, who had taken control of most of the eastern Frankish empire at that time.

As a central part of Lotharingia, the area of modern Limburg was still deeply involved in Frankish politics at this time. Zwentibold, claimant to the kingdom of Lotharingia, died in Susteren in 900, and had his support in the Kempen area. He was opposed by the local House of Reginar, who had also changed sides during the Viking incursions (and may have had Viking links, Ragnar being a Norse name). Despite their continuing conflicts with the emperors, it is from the house of Reginar that the medieval counts of Loon are thought to descend, although the exact genealogy of this house is highly uncertain.

The area of Belgian Limburg underwent two periods of conversion to Christianity. The first period was that of St Servatius, before the domination of the Franks. This was only lasting in the romanised area to the southeast of Limburg, around Tongeren, and including nearby Maastricht and Liège. A second period of missionary activity started around 700AD, after the coming of the pagan Franks, Lambert of Maastricht and Willibrord and others preached the gospel to the pagans who were still dominant to the north of this region. Out of these three romanised and early Christian cities, Liège became the eventual seat of the bishop in the Middle Ages, taking over this position from Maastricht, which had taken it over from Tongeren. Another early saint in the south of Limburg was St Trudo.

Middle Ages

Belgian Limburg corresponds closely to the medieval territory of the County of Loon (French Looz), which originally centred on the fortified town of Borgloon, which had somehow become the centre of power in the Haspengouw during the early Middle Ages, taking over from earlier counties such as Hocht, near the Maas (Hocht itself is in Lanaken today), and Avernas, near St Truiden (Avernas itself being in Hannut today). It expanded from this territory into the Kempen to eventually encompass a similar territory to that of modern Belgian Limburg. The counts then moved their courts and residences from Borgloon, which was close to the border to Liège, to more central positions in and around Hasselt, which has remained the capital of the region until today. As part of Loon, Belgian Limburg eventually became subject, not only spiritually but also politically, to the Prince Bishops of Liège.

Modern history

Loon, and the rest of the prince-bishopric of Liège, were not joined politically with the rest of what would become Belgium until the French revolution. Nevertheless, in the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries the population of Loon was constantly and badly affected by the wars involving neighbouring Brabant and Dutch Limburg, including the Eighty Years' War, the War of the Spanish Succession, the War of the Austrian Succession, the Seven Years' War, and even the Brabant Revolution against the unpopular reforms of the Emperor Joseph II. During this period the region's episcopal government was often unable to maintain law and order, and the economy of the area was often desperately bad, affected by plundering by soldiers and gangs of thieves such as the "Bokkenrijders". Nevertheless, the population contained strongly conservative catholic elements, and not only supported the Brabant revolution, but also rebelled unsuccessfully against the revolutionary French regime in the Peasants' War of 1798.

Almost none of the modern Belgian or Dutch provinces of Limburg were ever part of the nearby Duchy of Limburg. Nevertheless, Limburg's modern name derives from this Duchy, which originally centred upon the fortified castle town known as Limbourg, situated on the river Vesdre in the Ardennes, now in the Wallonian province of Liège. The modern Limburg region, containing the Belgian and Dutch provinces of that name, were first united within one province while under the power of revolutionary France, and later the Napoleonic empire, but then under the name of the French department of the Lower Meuse (Maas). Limbourg the town was not in this region, but was neighbouring it, and there had been a political association. Following the Napoleonic Era, the great powers (the United Kingdom, Prussia, the Austrian Empire, the Russian Empire and France) granted the region to the new United Kingdom of the Netherlands in 1815. A new province was formed and was to receive the name "Maastricht", after its capital. The first king, William I, who did not want the name Limbourg to be lost, given its high status of being an ancient Duchy, insisted that the name be changed to the "Province of Limburg".

When both the Dutch- and the French-speaking Catholic regions in the south of the new kingdom split away from the mainly Calvinist, Dutch north in the Belgian Revolution of 1830, the province of Limburg was at first almost entirely under Belgian rule, and the status of both Limburg and Luxembourg became unclear. Leopold I took the oath as King of the Belgians on 21 July 1831. During the "Ten days campaign", 2–12 August 1831, Dutch armies entered Belgium and took control of several cities, including Antwerp, in order to negotiate from a stronger position. Several Belgian militias and armies were easily defeated including the Belgian Army of the Meuse near Hasselt, on 8 August. A French army entered Belgium on 9 August, and the British also began to intervene, while the Netherlands' Prussian and Russian allies could not send support, leading to a ceasefire. In 1831 the Treaty of the Eighty Articles in London established that both Limburg and Luxemburg would be split between the two states. In 1832 Antwerp was finally forced from Dutch hands. Finally, in 1839, under a new "Treaty of London" Limburg and Luxemburg were split, Limburg being split into so-called Dutch Limburg and Belgian Limburg.

It is only in border areas near Maastricht that either of the two modern Limburgs have any strong historical connection to the old Duchy. For the most part this connection is only indirect, in the sense that a part of this area came to form a single detached territory under the Duchy of Brabant, thus ruled from its capital in Brussels, the so-called "States (Staten) of Limburg and Overmaas". However, one small part of Belgian Limburg was really in the Duchy of Limburg: in the extreme east of Voeren, the villages of Teuven and Remersdaal.

Twentieth century

Like other parts of eastern Belgium, Belgian Limburg came under German domination in the early phases of both the First World War and the Second World War.

In the Second World War, Limburg and the rest of Belgium was joined together with some "Germanic" parts of Northern France under the military administration of "Belgium and Northern France". This was unlike the Netherlands and Norway, where non-military puppet governments were installed. The eventual Nazi plan was that Limburg would become part of the Greater Germanic Reich.

Belgian Limburg became officially Flemish when all provinces in Belgium came under control of linguistically defined institutional regions in 1962. In the case of Voeren, surrounded by French speaking parts of Belgium, and having a significant population of French speakers, this was not without controversy.

Only in 1967, the Catholic Church created a bishopric of Hasselt, separate form the bishopric of Liège.

See also

References

- ↑ Rozoy (1998), "The (Re-)Population of northern France between 13,000 and 8000 BP" (PDF), Quaternary International, 49-50: 69–86, doi:10.1016/s1040-6182(97)00054-2

- ↑ Jappe (1974, p. 2)

- 1 2 Vermeersch, Pierre M., "La transition Ahrensbourgien-Mésolithique ancien en Campine belge et dans le Sud sableux des Pays-Bas" (PDF), Le début du Mésolithique du Nord-Ouest, Mémoire de la Société préhistorique française, XLV

- ↑ Boerderij uit de jonge steentijd ontdekt in Riemst

- 1 2 3 Vanmontfort (2007), "Bridging the gap. The Mesolithic-Neolithic transition in a frontier zone" (PDF), Documenta Praehistorica, 34

- ↑ Constantin; Ilett; Burnez-Lanotte (2011), ""La Hoguette, Limburg, and the Mesolithic"", in Vanmontfort; Kooijmans; Amkreutz, Pots, Farmers and Foragers: How Pottery Traditions Shed a Light on Social Interaction in the Earliest Neolithic of the Lower Rhine Area, Amsterdam University Press

- 1 2 Crombé; Vanmontfort (2007), "The neolithisation of the Scheldt basin in western Belgium" (PDF), Proceedings of the British Academy, 144

- ↑ Vanmontfort (2004), "Inhabitées ou invisibles pour l'archéologie" (PDF), Anthropologia et Praehistorica, 115

- ↑ "Tussen SOM en TRB, enige gedachten over het laat-Neolithicum in Nederland en België" (PDF), Bulletin voor de Koninklijke Musea voor Kunst en Geschiednis, 54, 1983

- ↑ Arnoldussen, Stijn (2008), A Living Landscape: Bronze Age Settlement Sites in the Dutch River Area, ISBN 9789088900105

- ↑ "Persée : Portail de revues en sciences humaines et sociales". persee.fr. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ↑ Hawkes, C.F.C.; Boardman, J.; Brown, A.; Powell, T.G.E. (1971). The European Community in Later Prehistory: Studies in Honour of C. F. C. Hawkes. Routledge and K. Paul. p. 218. ISBN 9780710069405. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ↑ https://oar.vioe.be/publicaties/AIVT/2/AIVT002-003.pdf

- ↑ Bonnie, Rick (2009), Cadastres, misconceptions & Northern Gaul: a case study from the Belgian, ISBN 9789088900242

- ↑ Lamarcq & Rogge (1996)

- ↑ Wightman (1985)

- 1 2 3 "Gallic Wars" II.4

- 1 2 "Gallic War" VI.32

- ↑ Lamarcq & Rogge (1996, p. 44)

- 1 2 "Germania" chapter 2

- ↑ "Gallic War" V.24

- ↑ "Gallic War" V.27

- ↑ "Gallic War" V.38

- 1 2 "Gallic War" VI.34

- ↑ "Gallic War" VI.33

- ↑ "Gallic War" VI.31

- ↑ Wightman (1985, p. 202)

- ↑ Wightman (1985, p. 104)

- ↑ Wightman (1985, pp. 53–54)

Bibliography

- Jappe Alberts (1974), Geschiedenis van de Beide Limburgen, Van Gorcum

- Bonnie, Rick (2009), Cadastres, misconceptions & Northern Gaul: a case study from the Belgian Hesbaye region

- Lamarcq, Danny; Rogge, Marc (1996), De Taalgrens: Van de oude tot de nieuwe Belgen, Davidsfonds

- Roymans, Nico (2004), Ethnic Identity and Imperial Power. The Batavians in the Early Roman Empire, Amsterdam Archaeological Studies 10, ISBN 9789053567050

- Vanderhoeven, Alain; Vanderhoeven, Michel (2004), "Confrontation in Archaeology: Aspects of Roman Military in Tongeren", in Vermeulen, Frank; Sas, Kathy; Dhaeze, Wouter, Archaeology in Confrontation: Aspects of Roman Military Presence in the Northwest (Studies in Honour of Prof. Em. Hugo Thoen), Ghent University, p. 143, ISBN 9789038205786

- Vanvinckenroye, Willy (2001), "Über Atuatuca, Cäsar und Ambiorix", Belgian archaeology in a European setting, 2, ISBN 9789058671677

- Wightman, Edith Mary (1985), Gallia Belgica, University of California Press, ISBN 9780520052970