History of homosexuality in American film

Since the transition into the modern-day gay rights movement, homosexuality has appeared more frequently in American film and cinema. Compared to the 1900s, it is clear that the greater acceptance of homosexuality in the modern era has allowed more queer characters and issues to be seen with more respect and understanding in film and cinema.

Early films and productions

The first notable form of homosexuality depicted in film was in 1895 between two men dancing together in the William Kennedy Dickson motion picture The Dickson Experimental Sound Film, commonly labeled online and in three published books as The Gay Brothers. Though, at the time, men were not seen this way as queer or even flamboyant, but merely acting fanciful.[1] Film critic Parker Tyler stated that the scene "shocked audiences with its subversion of conventional male behavior."[2] During the late nineteenth century and into the 1920s–30s, homosexuality was largely depicted in gender-based conventions and stereotypes. Oftentimes male characters intended to be identified as gay were flamboyant, effeminate, humorous characters in film.[3] The terms "pansy" and "sissy" became tagged to homosexuality and was described as "a flowery, fussy, effeminate soul given to limp wrists and mincing steps."[3] Because of his high-pitched voice and attitude, the pansy easily transitioned from the silent film era into the talking pictures where those characteristics could be taken advantage of.[3]

During the period of the Great Depression in the late 1920s, the cinema audience had decreased significantly. Filmmakers produced movies with themes and images that had high shock-value to get people returning to the theaters. This called for the inclusion of more controversial topics such as prostitution and violence, creating a demand for pansies and their lesbian counterparts to stimulate or shock the audience.[3] With the new influx of these provocative subjects, debates arose regarding the negative effects these films could have on American society.

It was during this same time that the United States Supreme Court ruled that films did not have First Amendment protection and several local governments passed laws restricting the public exhibition of "indecent" or "immoral" films. The media publicity surrounding several high-profile celebrity scandals and the danger of church-led boycotts also pressured the leadership within the film industry to establish a national censorship board, which became the Motion Picture Production Code.

The Motion Picture Production Code, also simply known as the Production Code or as the "Hays Code", was established both to curtail additional government censorship and to prevent the loss of revenue from boycotts led by the Catholic Church and fundamentalist Protestant groups. In terms of homosexuality, the code marked the end of the "pansy" characters and the beginning of depictions that were more reserved and buried within subtext.[3] An example for the enforcement of the production code is the character Joel Cairo in the movie Maltese Falcon. in the original novel the character is clearly homosexual, however in the movie it is vague.[4]

Early gender-role reversals

The time period prior to the "Hays Code" also included many gender role-reversal productions, notably Charlie Chaplin's A Woman (1915), in which Chaplin dresses as a female and plays with the affection of various men.[2] Famous series of drag impersonations included Miss Fatty (1915), featuring Fatty Arbuckle, and Sweedie (1914–16), starring Academy Award-winning actor Wallace Beery, created a comedic view of drag that many in the late 1910s and early 1920s could find entertaining. These depictions became rarer for mainstream commercial films with the establishment of the Hollywood Production Code[2] Various other notable drag films of the early to mid-1900s include:

- A Florida Enchantment (1914), directed by and starring Sidney Drew

- Mabel's Blunder (1914), directed by and starring Mabel Normand

- Sylvia Scarlett (1936), starring Katharine Hepburn, a widely unsuccessful film, but significant due to the female-to-male transformation[5]

- I Was a Male War Bride (1949), directed by Howard Hawks and starring Cary Grant as a French officer who must impersonate a female war bride.

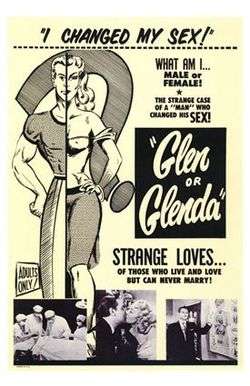

- Glen or Glenda (1953), a film by Ed Wood starring himself

- Some Like It Hot (1959), featuring Tony Curtis, Marilyn Monroe, and Jack Lemmon

World War II era to 1960s

During the Second World War and the subsequent Cold War, Hollywood increasingly depicted gay men and women as sadists, psychopaths, and nefarious, anti-social villains. These depictions were driven by the censorship of the code, which was willing to allow "sexual perversion" if it was depicted in a negative manner, as well as the fact that homosexuality was classified as a mental illness and gay men and women were often harassed by the police. This can be examined in Alfred Hitchcock's 1948 film Rope.[1][2] In his article "The History of Gays and Lesbians on Film", author Daniel Mangin explains:

- "In the film, Jimmy Stewart plays a dabbler in philosophy who introduces the two boys to the "Superman" theory of the superiority of some humans over others. He becomes horrified when he realizes that the theories he espoused have led to murder. His character's somewhat hysterical repudiation of his formerly held beliefs mirrored the fears of some Americans about the infiltration of alien ideas. That the homosexuals in Rope were connected to the arts, as were many of those investigated, seems apt in view of longstanding suspicions about the politics and sexual practices of people so engaged."[2]

The censorship code gradually became liberalized 1950s–60s, until it was replaced by the current classification system established by the Motion Picture Association of America. Legally, it was in the mid-1950s when the United States Supreme Court extended First Amendment legal protection to films, reversing its original verdict, and, in a second case, ended once common practice of film studios owning the cinemas. That practice had made it difficult for films produced outside of these studios, such as independent or international films, to be screened widely, let alone to be commercially successful.

Culturally, American consumers were increasingly less likely to boycott a film at the request of the Catholic Church or fundamentalist Protestant groups. This meant that films with objectionable content did not necessarily need the approval of the Hollywood Production Code or religious groups in order to be successful. As a result, Hollywood gradually became more willing to ignore the code in order to compete with television and the growing access to independent and international cinema.

During the 1950s–60s, gay characters in American films were identified with more overtly sexual innuendos and methods, but having a gay or bisexual sexual orientation was largely treated as a trait of miserable and suicidal misfits who frequently killed themselves or other people.[6]

During this post-war era, mainstream American cinema might advocate tolerance for eccentric, sensitive young men, wrongly, accused of homosexuality, such as in the film adaptation of Tea and Sympathy (1956), but gay characters were frequently eliminated from the final cut of the film or depicted as dangerous misfits who would fall prey to a well-deserved violent end.

The 1965 film Inside Daisy Clover, based on the novel of the same name, was one of the first mainstream American films during the 1950s–60s to depict an expressly gay or bisexual character who, while forced to marry a woman for his career, is not uncomfortable with his sexual orientation and does commit suicide or fall victim to murder. Yet, beyond a few lines of dialogue, the character's bisexuality was largely restricted to bits of subtext and innuendo.

In America, efforts at creating complex gay or bisexual film characters were largely restricted to people such as Andy Warhol and Kenneth Anger. Beyond their underground, independent films, a handful of foreign films were depicting gay characters as complex human beings entitled to tolerance, if not equality. However, mainstream American cinema efforts at marketing films for a LGBT audience did not begin until the 1970s.

After Stonewall

Following the 1969 Stonewall riots in New York City (a major turning point in the LGBT-rights movement), Hollywood began to look at gay people as a possible consumer demographic. It was also in the 1970s, that some anti-gay laws and prejudicial attitudes changed through the work of an increasingly visible LGBT-rights movement and overall attitudes in America about human sexuality, sex and gender roles changed as a result of LGBT-rights, women's liberation and the sexual revolution.

The Boys in the Band (1970) was the first attempt of Hollywood to market a film to gay consumers and present an honest look at what it meant to be a gay or bisexual man in America. The film based, based on a play of the same name, was often hailed in the mainstream press as a presenting a "landmark of truths", but was often criticized for reinforcing certain anti-gay stereotypes and for failing to deal with LGBT-rights and showing a group of gay and bisexual men who are all unhappy, miserable and bitchy.

In contrast, Fortune and Men's Eyes (1971), was co-produced by MGM, dealt with the issue of homosexuality in prison, and depicted gays in a relatively "open and realistic, non-stereotypical and non-caricatured manner".[7]

Despite the criticism and setbacks with the Boys in the Band film, the treatment of homosexuality in mainstream American film did, gradually, improve during the 1970s, especially if the film was directed at a gay audience (i.e. A Very Natural Thing (1973)), or a more cosmopolitan-liberal audience (i.e. Something for Everyone (1970), Sunday Bloody Sunday (1971), Cabaret (1972) and Ode to Billy Joe (1976)).[1]

Despite the growing tolerance of homosexuality during the 1970s, some Hollywood films throughout the decade still depicted homosexuality as an insult or a joke. Gay characters were sometimes depicted in mainstream films as dangerous misfits who needed to be cured or killed. Some films would even use anti-gay derogatory comments, often made by the protagonist, in a manner that was not done in Hollywood films with regards to other minority groups. Films like Cruising (1980) and Windows, for example, portrayed gays in an unrelentingly negative light.

The slowly growing acceptance of homosexuality in film continued into the early 1980s, with the addition of two new factors; the rising political clout of Christian fundamentalist groups, committed to a conservative, traditionalist social and economic agenda, and the emergence of the HIV/AIDS pandemic.

Following decades

In the mid-1980s, an organized religious-political movement arose in America to oppose LGBT rights. The political clout of the "religious right", as it became known, grew as its role in helping to elect, mostly, Republican Party candidates and move the party further to the political right. Culturally, the clout of the organization came from its ability to mobilize not only for "pro-family" candidates but also mobilize boycotts and protests against a film, television series, music or literature that offended the beliefs or values of Christian fundamentalists.

As a result, a Hollywood film in the mid-1980s that depicted gay people as being complex human beings entitled to their rights and dignity was a potential commercial liability and was at risk of a boycott from the stronghold conservative, right wing movement. Throughout the 1980s, if a Hollywood film was not made, primarily, for a gay audience or a cosmopolitan–liberal audience, homosexuality was often depicted as something to laugh at, pity or fear.

Along with clout of fundamentalist Christian groups, the Hollywood's treatment of homosexuality and gay characters was also shaped by the emergence of the HIV/AIDS pandemic. Ignorance about the disease, and how it was spread, was commonplace and the fact that many of the early American victims were gay or bisexual men helped to fuel the myth that gave the disease its first name; GRID (Gay Related Immune Disorder).

As mainstream American films began to depict or make reference to the pandemic, the ignorance about the disease, including the idea that if one is gay, then they must have AIDS, spread.[1][3] The first American film about the pandemic, and the ignorance and homophobia that it promoted, was an independent film, Parting Glances (1986). It was followed by a mainstream television movie, An Early Frost (1985), but the first mainstream Hollywood film about the pandemic, and its impact on the gay community, would be released at the end of the decade; Longtime Companion (1989), followed up by Philadelphia (1993) a few years later.

All of these initial films and television movies about the pandemic followed a similar demographic pattern in that person living with AIDS was a white man from a middle-class or upper-class family, who was usually somber and emotional.[1] Though, homosexual characters and the disease were often shown in a negative light, they were also shown together as something manageable and "okay".[1]

In the late 1980s and into the 1990s, the cultural and political backlash that had occurred against gay people and gay rights issues began to decline, impacting how Hollywood treated LGBT-issues. The clout of Christian fundamentalist had its limits; in 1988, Pat Robertson, a prominent Christian fundamentalist, ran for president in the Republican Party primary and was soundly defeated. During the decade, more LGBT people had come out, including celebrities and politicians and the AIDS-HIV pandemic had forced the broader society to more openly talk about human sexuality, including homosexuality.

A younger, "queerer" generation of gay people were not only coming out at younger ages, but becoming involved in helping to build what became known, in the early – mid-1990s, as "Queer Cinema".[8]

Modern-day film

New Queer Cinema of the 1990s represented a new era of independent films. Often directed and or written by openly gay people they featured mostly LGBT characters who were open about their sexual orientation or gender identity and oftentimes openly rejected both homophobia (and transphobia) as well as the idea that all LGBT characters in film needed to be "positive" or politically correct role models.

Alongside these independent films, mainstream Hollywood increasingly began to treat homosexuality as a normal part of human sexuality and gay people as a minority group, entitled to dignity and respect. Overt bigotry against gay people on screen became akin to overt racism, sexism or anti-Semitism. A-list Hollywood stars were more eager to play a gay character in a film.

Initially, most of these Hollywood depictions were in the context of campy, funny characters, often in drag on some sort of adventure or farce, while teaching a lesson in tolerance, if not equality.[3] Drag portrayals also made a comeback in many films of the 1990s, notably The Birdcage (1996), starring Robin Williams and Nathan Lane, Mrs. Doubtfire (1993), also starring Robin Williams, The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert (1994), starring Guy Pearce, and To Wong Foo, Thanks for Everything! Julie Newmar (1995), starring Patrick Swayze, Wesley Snipes, and John Leguizamo.

While likable, decent gay characters were more common in mainstream Hollywood films, same-sex relationships, public displays of affection and intimacy were still generally taboo in mainstream Hollywood films. In the 1990s, the protagonist, or his best friend, in a Hollywood film could be LGBT, and a decent person, but, compared to heterosexual characters in films, the price of this progress was little to no on-screen same-sex intimacy or sexuality.

Outside of independent films or films made primarily for a gay audience, this trend did not really change in America until Ang Lee's Brokeback Mountain (2005), which was a major benchmark in modern gay cinema.[9] It was one of the first major motion pictures to feature a love story with two leading homosexual roles. The film provided a new mainstream outlook of homosexuality on film and in society. Other films such Boys Don't Cry (1999), Monster (2003), Milk (2008), and Black Swan (2010) all feature famous actors and actresses portraying homosexual characters searching for love and happiness in oppressive societies. It has become very frequent in modern cinema to see these types of lead roles being played by popular celebrities, which was quite rare decades before.

As the gay rights movement still paves the way for LGBT acceptance in all different aspects in American society, it has clearly created the possibilities of seeing homosexual roles in everyday television and film. It is no longer a full-out moral issue to see two men or women fall in love, have fun, and be themselves on camera. Though it is still slightly controversial to create homosexual characters in leading roles, the public has grown very comfortable and has progressed with improving the quality of gay themes and images.[3]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Morris, Gary. "A Brief History of Queer Cinema". GreenCine. Retrieved November 17, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Mangin, Daniel (1989). "College Course File: The History of Gays and Lesbians on Film". Journal of Film and Video. University of Illinois Press. 41 (3): 50–66. JSTOR 20687868.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Benshoff, Harry M.; Griffin, Sean (2005). Queer images: A History of Gay and Lesbian Film in America. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. ISBN 0742519724.

- ↑ Murray, Raymond (January 1995). Images in the Dark. Philadelphia: TLA Publications. p. 501. ISBN 1-880707-01-2.

- ↑ Noe, Denise (2001). "Can a woman be a man on-screen?". The Gay and Lesbian Review. Retrieved November 24, 2012.

- ↑ Gamson, Joshua (2009). "Sweating in the Spotlight: Lesbian, Gay and Queer Encounters with Media and Popular Culture". In Richardson, Diane; Seidman, Steven. Handbook of Lesbian and Gay Studies. Sage Publications. pp. 339–54. ISBN 9780761965114.

- ↑ http://www.canadiantheatre.com/dict.pl?term=Fortune%20and%20Men%27s%20Eyes

- ↑ Michael D. Klemm. "Proud". Outcome Buffalo.

- ↑ Piontek, Thomas (2012). "Tears for Queers: Ang Lee's Brokeback Mountain, Hollywood, and American Attitudes toward Homosexuality". The Journal of American Culture. 35 (2): 123–34. doi:10.1111/j.1542-734X.2012.00802.x. ISSN 1542-7331. PMID 22737731.