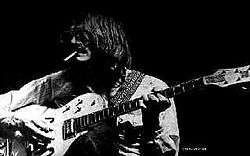

Danny Whitten

| Danny Whitten | |

|---|---|

| |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Danny Ray Whitten |

| Born |

May 8, 1943 Columbus, Georgia, U.S. |

| Died |

November 18, 1972 (aged 29) Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Genres | Hard rock, country rock, blues-rock |

| Occupation(s) | Musician, songwriter |

| Instruments | Guitar, vocals |

| Years active | 1962–1972 |

| Labels | Liberty, Valiant, Loma, a division of Autumn, White Whale, Reprise |

| Associated acts | Danny & The Memories, The Psyrcle, Bonnett & Mountjoy, The Rockets, Crazy Horse, Neil Young |

| Website |

www |

Daniel Ray Whitten (May 8, 1943 – November 18, 1972) was an American musician and songwriter best known for his work with Neil Young's backing band Crazy Horse, and for the song "I Don't Want To Talk About It", a hit for Rod Stewart and Everything but the Girl.

Biography

Early years

Whitten was born on May 8, 1943, in Columbus, Georgia. His parents split up when he was young. He and his sister, Brenda, lived with their mother, who worked long hours as a waitress.[1] His mother remarried when he was 9 and the family moved to Canton, Ohio.[1]

Musical beginnings

Whitten joined Billy Talbot and Ralph Molina among others in the doo-wop group Danny and the Memories. After recording an obscure single, "Can't Help Loving That Girl of Mine", core members of the group moved to San Francisco where they morphed into a folk-psychedelic rock act called The Psyrcle. Whitten played guitar, Molina drums, and Talbot played bass and piano.

By 1967, the group took on brothers George and Leon Whitsell on additional guitars and vocals, as well as violinist Bobby Notkoff, the sextet calling themselves The Rockets. They signed with independent label White Whale Records, working with producer Barry Goldberg for the group's self-titled album in mid-1968. The album sold poorly.

Connection with Neil Young

Songwriter Neil Young, fresh from departing the Buffalo Springfield, with one album of his own under his belt, began jamming with the Rockets and expressed interest in recording with Whitten, Molina and Talbot. The trio agreed, so long as they were allowed to simultaneously continue on with The Rockets: Young acquiesced initially, but imposed a rehearsal schedule that made that an impossibility. At first dubbed "War Babies" by Young, they soon became known as Crazy Horse.

Recording sessions led to Young's second album, Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere, credited as Neil Young with Crazy Horse, with Whitten on second guitar and vocals. Although his role was that of support, Whitten sang the album's opening track "Cinnamon Girl" along with Young, and Whitten and Young played guitar on "Down by the River" and "Cowgirl in the Sand". These tracks would influence the grunge movement of the 1990s, and all three songs would be counted among Young's most memorable work, continuing to hold a place in his performance repertoire to this day.

Drug addiction

Whitten began using heroin and quickly became addicted. Although he participated in the early stages of Young's next solo effort, After the Gold Rush, Whitten and the rest of Crazy Horse were dismissed about halfway through the recording sessions, in part because of Whitten's heavy drug use. Whitten performs on "Oh, Lonesome Me", "I Believe in You", and "When You Dance I Can Really Love". Young wrote and recorded "The Needle and the Damage Done" during this time, with direct references to Whitten's addiction and its role in the destruction of his talent.

Acquiring a recording contract and expanded to a quintet in 1970, Crazy Horse recorded its first solo album, released in early 1971. The debut album included five songs by Whitten, with two standout tracks being a song co-written by Young which would show up later on a Young album, "(Come On Baby Let's Go) Downtown", and Whitten's most famous composition, "I Don't Want To Talk About It", a heartfelt ballad that would receive many cover versions and offer the promise of unfulfilled talent.

Death

Whitten continued to drift, his personal life ruled almost totally by drugs. He was kicked out of Crazy Horse by Talbot and Molina, who used replacements on the band's two albums of 1972. In October of that year, after receiving a call from Young to play rhythm guitar on the upcoming tour behind Young's Harvest album, Whitten showed up for rehearsals at Young's home outside San Francisco. While the rest of the group hammered out arrangements, Whitten lagged behind, figuring out the rhythm parts, though never in sync with the rest of the group. Young, who had more at stake after the success of After The Gold Rush and Harvest, fired him from the band on November 18, 1972. Young gave Whitten $50 and a plane ticket back to Los Angeles. Later that night Whitten died from a fatal combination of Valium, which he was taking for severe knee arthritis, and alcohol, which he was using to try to get over his heroin addiction.[2]

Neil Young recalled, "We were rehearsing with him and he just couldn't cut it. He couldn't remember anything. He was too out of it. Too far gone. I had to tell him to go back to L.A. 'It's not happening, man. You're not together enough.' He just said, 'I've got nowhere else to go, man. How am I gonna tell my friends?' And he split. That night the coroner called me and told me he'd died. That blew my mind. Fucking blew my mind. I loved Danny. I felt responsible. And from there, I had to go right out on this huge tour of huge arenas. I was very nervous and ... insecure.”[3]

Years later, Young told biographer Jimmy McDonough that for a long time after Whitten died, he felt responsible for Whitten's death. It took him years to stop blaming himself. "Danny just wasn't happy", Young said. "It just all came down on him. He was engulfed by this drug. That was too bad. Because Danny had a lot to give, boy. He was really good."

Discography

- Surfin' Granny, 'A' Side. Mirror Mirror, 'B' Side. Danny and the Memories, Single, Liberty label 1963 (Not Released)

- Can't Help Loving That Girl of Mine, 'A' Side. Don't Go, 'B' Side. Danny and the Memories, Single, Valiant label 1964

- Baby Don't Do That, 'A' Side. 'B' Side, Unknown. The Psyrcle, Single, Loma label 1966 (Not Released)

- The Rockets, The Rockets, Album, White Whale label, 1968

- Hole In My Pocket, The Rockets, Single, White Whale label, 1968 (Promotional release only)

- Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere, Neil Young and Crazy Horse, Album, Reprise label 1969

- After the Gold Rush, Neil Young, Album, Reprise label 1970

- Crazy Horse, Crazy Horse, Album, Reprise label 1971

- Dirty Dirty 'A' Side, Beggar's Day 'B' Side, Crazy Horse, Single, Reprise label 1971

- Downtown 'A' Side, Dance Dance Dance 'B' Side, Crazy Horse, Single, Reprise label 1971

- Hole In My Pocket on Blast From My Past, Barry Goldberg, Album, Buddah label 1971

- Tonight's the Night, Neil Young, album, Reprise 1975 (posthumous)

- Gone Dead Train: The Best of Crazy Horse 1971–1989 Crazy Horse, Album Reprise label 2005

- Scratchy: The Complete Reprise Recordings, Crazy Horse, Album Reprise label 2005

- Live at the Fillmore East Neil Young & Crazy Horse, Album, Reprise 2006 (recorded 1970)

Songs written by Danny Whitten

- "Dance To The Music On The Radio" (D Whitten/B Talbot)

- "Dirty, Dirty" (D Whitten)

- "(Come On Baby Let's Go) Downtown" (D Whitten/N Young)

- "Hole in My Pocket (The Rockets song)" (D Whitten) 1958 single, produced Barry Goldberg, rerecorded by the Barry Goldberg Reunion

- "I Don't Need Nobody (Hangin' Round My Door)" (D Whitten)

- "I Don't Want to Talk About It" (D Whitten)

- "I'll Get By" (D Whitten)

- "Let Me Go" (D Whitten)

- "Look at All the Things"" (D Whitten)

- "Love Can Be So Bad" (D Whitten/L Vegas)

- "May" (D Whitten/B Talbot)

- "Mr Chips" (D Whitten)

- "Oh Boy" (D Whitten)

- "Wasted" (D Whitten/L Vegas/P Vegas)

- "Whatever" (D Whitten/B Talbot)

- "Won't You Say You'll Stay" (D Whitten)

See also

Notes

- 1 2 McDonough, Jimmy. Shakey: Neil Young's Biography, p. 274

- ↑ Michael St. John. Downtown: The Danny Whitten Story. Self-published 2012. http://www.dannyraywhitten.com/bookpdf.html

- ↑ Quoted in Heatley, Michael (1997). Neil Young: In His Own Words, p. 27. Omnibus Press.