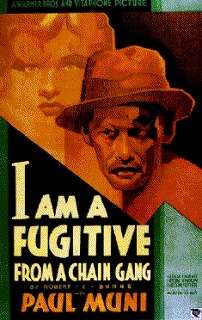

I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang

| I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang | |

|---|---|

Movie poster | |

| Directed by | Mervyn LeRoy |

| Produced by | Hal B. Wallis |

| Screenplay by |

Howard J. Green Brown Holmes |

| Based on |

I Am a Fugitive from a Georgia Chain Gang! by Robert E. Burns |

| Starring |

Paul Muni Glenda Farrell Helen Vinson Noel Francis |

| Music by | Bernhard Kaun |

| Cinematography | Sol Polito |

| Edited by | William Holmes |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 93 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang (1932) is an American Pre-Code crime-drama film directed by Mervyn LeRoy and starring Paul Muni as a wrongfully convicted convict on a chain gang who escapes to Chicago. It was released in November 10, 1932. The film received positive reviews and three Academy Award Nominations.

The film was written by Howard J. Green and Brown Holmes from Robert Elliott Burns's autobiography of a similar name "I Am a Fugitive from a Georgia Chain Gang!" serialised in the True Detective magazine.[2] The true life story was later recreated in the television movie, The Man Who Broke a 1,000 Chains (1987) starring Val Kilmer.[3]

In 1991, this film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".

Plot

Sergeant James Allen (Paul Muni) returns to civilian life after World War I but his war experience makes him restless. His family feels he should be grateful for a tedious job as an office clerk, and when he announces that he wants to become an engineer, they react with outrage. He leaves home to find work on any sort of project, but unskilled labor is plentiful and it's hard for him to find a job. Wandering and sinking into poverty, he accidentally becomes caught up in a robbery and is sentenced to ten years on a brutal Southern chain gang.

He escapes and makes his way to Chicago, where he becomes a success in the construction business. He becomes involved with the proprietor of his boardinghouse, Marie Woods (Glenda Farrell), who discovers his secret and blackmails him into an unhappy marriage. He then meets and falls in love with Helen (Helen Vinson). When he asks his wife for a divorce, she betrays him to the authorities. He is offered a pardon if he will turn himself in; Allen accepts, only to find that it was just a ruse. He escapes once again.

In the end, Allen visits Helen in the shadows on the street and tells her he is leaving forever. She asks, "Can't you tell me where you're going? Will you write? Do you need any money?" James repeatedly shakes his head in answer as he backs away. Finally Helen says, "But you must, Jim. How do you live?" James' face is barely seen in the surrounding darkness, and he replies, "I steal," as he backs into the black.

Cast

Development and production A scene from the film trailer for I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang. The film was based on a book written by Robert Elliott Burns in 1932 and published by Grosset & Dunlap. The book tells the story of Burns' imprisonment on a chain gang in Georgia in the 1920s, his subsequent escape and the furor that developed. The story was first published in January 1932, serialized in True Detective Mysteries magazine. Despite Jack L. Warner and Darryl F. Zanuck's personal interest in adapting Burns's book, the Warner Bros. story department voted against it with a report that concluded: "this book might make a picture if we had no censorship, but all the strong and vivid points in the story are certain to be eliminated by the present censorship board." The story editor listed specific reasons for not recommending the book for a picture, most of them having to do with the violence of the story and the uproar that was sure to explode in the Deep South. In the end, Warner and Zanuck had the final say and approved the project. Roy Del Ruth, the highest-paid director of the Warner Bros. Studio, was assigned to direct, but the contract director refused the assignment. In a lengthy memo to supervising producer Hal B. Wallis, Del Ruth explained his decision: "This subject is terribly heavy and morbid...there is not one moment of relief anywhere." Del Ruth further argued that the story "lacks box-office appeal," and that offering a depressing story to the public seemed ill timed, given the harsh reality of the Great Depression outside the walls of the local neighborhood cinema. Mervyn LeRoy, who was at that time directing 42nd Street (which came out in 1933), dropped out of the shooting and left the reigns to Lloyd Bacon. LeRoy cast Paul Muni in the role of James Allen after seeing him in a stage production of "Counsellor-at-Law". Muni was not impressed with LeRoy upon first meeting him in Warner's Burbank office. Despite this meeting, Muni and LeRoy became close friends. LeRoy was present at Muni's funeral in 1967 along with the actor's agent. To prepare for the role, Muni conducted several intensive meetings with Robert E. Burns in Burbank in order to capture the way the real fugitive walked and talked, in essence, to catch "the smell of fear." Muni stated to Burns: "I don't want to act like you, I want to be you." Muni also set the Warner Bros. research department on a quest to procure every available book and magazine article about the penal system. Muni also met with several California prison guards, even one who had worked in a Southern chain gang. Muni fancied the idea of meeting with a guard or warden still working in Georgia, but Warner studio executives quickly rejected his suggestion. The final line in the film "But you must, Jim. How do you live?" "I steal" replied by James is among the most famous closing lines in American film.[4] Director Mervyn LeRoy later claimed that the idea for James' retreat into darkness came to him when a fuse blew on the set, but in fact it was written into the script.[4] Impact on American societyAudiences in the United States who saw the film began to question the legitimacy of the United States legal system,[5] and in January 1933 the film's protagonist, Robert Elliot Burns, who was still imprisoned in New Jersey, and a number of other chain gang prisoners nationwide in the United States were able to appeal and were released.[6] In January 1933, Georgia chain gang warden J. Harold Hardy, who was also made into a character in the film, sued the studio for displaying "vicious, brutal and false attacks" against him in the film.[7] Awards and nominationsAcademy Award Nominations:[8] National Board Review Award:

Other Wins:

Further reading

See alsoReferences

External links

|