Jenny Lind

by Eduard Magnus, 1862

Johanna Maria Lind (6 October 1820 – 2 November 1887), better known as Jenny Lind, was a Swedish opera singer, often known as the "Swedish Nightingale". One of the most highly regarded singers of the 19th century, she performed in soprano roles in opera in Sweden and across Europe, and undertook an extraordinarily popular concert tour of America beginning in 1850. She was a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Music from 1840.

Lind became famous after her performance in Der Freischütz in Sweden in 1838. Within a few years, she had suffered vocal damage, but the singing teacher Manuel García saved her voice. She was in great demand in opera roles throughout Sweden and northern Europe during the 1840s, and was closely associated with Felix Mendelssohn. After two acclaimed seasons in London, she announced her retirement from opera at the age of 29.

In 1850, Lind went to America at the invitation of the showman P. T. Barnum. She gave 93 large-scale concerts for him and then continued to tour under her own management. She earned more than $350,000 from these concerts, donating the proceeds to charities, principally the endowment of free schools in Sweden. With her new husband, Otto Goldschmidt, she returned to Europe in 1852 where she had three children and gave occasional concerts over the next two decades, settling in England in 1855. From 1882, for some years, she was a professor of singing at the Royal College of Music in London.

Life and career

Early years

Born in Klara, in central Stockholm, Lind was the illegitimate daughter of Niclas Jonas Lind (1798–1858), a bookkeeper, and Anne-Marie Fellborg (1793–1856), a schoolteacher.[1] Lind's mother had divorced her first husband for adultery but, for religious reasons, refused to remarry until after his death in 1834. Lind's parents married when she was fourteen.[1]

Lind's mother ran a day school for girls out of her home. When Lind was about nine years old, her singing was overheard by the maid of Mademoiselle Lundberg, the principal dancer at the Royal Swedish Opera.[1] The maid, astounded by Lind's extraordinary voice, returned the next day with Lundberg, who arranged an audition and helped her gain admission to the acting school of the Royal Dramatic Theatre, where she studied with Karl Magnus Craelius, the singing master at the theatre.[2]

Lind began to sing onstage when she was ten. She had a vocal crisis at the age of 12 and had to stop singing for a time, but recovered.[2] Her first great role was Agathe in Weber's Der Freischütz in 1838 at the Royal Swedish Opera.[1] At age 20 she was a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Music and court singer to the King of Sweden and Norway. Her voice became seriously damaged by overuse and untrained singing technique, but her career was saved by the singing teacher Manuel García, with whom she studied in Paris from 1841 to 1843. So damaged was her voice that he insisted that she should not sing at all for three months, to allow her vocal cords to recover, before he started to teach her a secure vocal technique.[1][2]

After Lind had been with García for a year, the composer Giacomo Meyerbeer, an early and faithful admirer of her talent, arranged an audition for her at the Opéra in Paris, but she was rejected. The biographer Francis Rogers concludes that Lind strongly resented the rebuff: when she became an international star, she always refused invitations to sing at the Paris Opéra.[3] Lind returned to the Royal Swedish Opera, greatly improved as a singer by García's training. She toured Denmark where, in 1843, Hans Christian Andersen met and fell in love with her. Although the two became good friends, she did not reciprocate his romantic feelings. She is believed to have inspired three of his fairy tales: "Beneath the Pillar", "The Angel" and "The Nightingale".[4] He wrote, "No book or personality whatever has exerted a more ennobling influence on me, as a poet, than Jenny Lind. For me she opened the sanctuary of art."[4] The biographer Carol Rosen believes that after Lind rejected Andersen as a suitor, he portrayed her as The Snow Queen with a heart of ice.[1]

German and British success

In December 1844, through Meyerbeer's influence, Lind was engaged to sing the title role in Bellini's opera Norma in Berlin.[3] This led to more engagements in opera houses throughout Germany and Austria, although such was her success in Berlin that she continued there for four months before leaving for other cities.[2] Among her admirers were Robert Schumann, Hector Berlioz and, most importantly for her, Felix Mendelssohn. Ignaz Moscheles wrote: "Jenny Lind has fairly enchanted me ... her song with two concertante flutes is perhaps the most incredible feat in the way of bravura singing that can possibly be heard".[5] This number, from Meyerbeer's Ein Feldlager in Schlesien (The Camp of Silesia, 1844; a role written for Lind but not premiered by her) became one of the songs most associated with Lind, and she was called on to sing it wherever she performed in concert.[1] Her operatic repertoire comprised the title roles in Lucia di Lammermoor, Maria di Rohan, Norma, La sonnambula and La vestale, as well as Susanna in The Marriage of Figaro, Adina in L'elisir d'amore and Alice in Robert le diable. About this time she became known as "the Swedish Nightingale". In December 1845, the day after her debut at the Leipzig Gewandhaus under the baton of Mendelssohn, she sang without fee for a charity concert in aid of the Orchestra Widows' Fund. Her devotion and generosity to charitable causes remained a key aspect of her career and greatly enhanced her international popularity even among the unmusical.[1]

At the Royal Swedish Opera, Lind had been friends with the tenor Julius Günther. They sang together both in opera and on the concert stage, becoming romantically linked by 1844. Their schedules separated them, however, as Günther remained in Stockholm and then became a student of Garcia's in Paris in 1846–1847. Reunited after this in Sweden, according to Lind's 1891 Memoir, they became engaged to marry in the spring of 1848 just before Lind returned to England. However, the two broke off the engagement in October of the same year.[6]

After a successful season in Vienna, where she was mobbed by admirers and feted by the Imperial Family,[2] Lind traveled to London and gave her first performance there on 4 May 1847 when she appeared in an Italian version of Meyerbeer's Robert le Diable. This was attended by Queen Victoria; the next day, The Times wrote:

- We have had frequent experience of the excitement appertaining to "first nights", but we may safely say, and our opinion will be backed by several hundreds of Her Majesty's subjects, that we never witnessed such a scene of enthusiasm as that displayed last night on the occasion of Mademoiselle Jenny Lind's début as Alice in an Italian version of Robert le Diable.[7]

In July 1847, she starred in the world première of Verdi's opera I masnadieri at Her Majesty's Theatre's, under the baton of the composer.[8] During her two years on the operatic stage in London, Lind appeared in most of the standard opera repertory.[3] Early in 1849, still in her twenties, Lind announced her permanent retirement from opera. Her last opera performance was on 10 May 1849 in Robert le diable; Queen Victoria and other members of the Royal Family were present.[9] Lind's biographer Francis Rogers has written, "The reasons for her early retirement have been much discussed for nearly a century, but remain today a matter of mystery. Many possible explanations have been advanced, but not one of them has been verified."[3]

Lind and Mendelssohn

In London, Lind's close friendship with Mendelssohn continued. There has been strong speculation that their relationship was more than friendship. Papers confirming this were alleged to exist, although their contents had not been made public.[10] However, in 2013 George Biddlecombe confirmed in the Journal of the Royal Musical Association that "The Committee of the Mendelssohn Scholarship Foundation possesses material indicating that Mendelssohn wrote passionate love letters to Jenny Lind entreating her to join him in an adulterous relationship and threatening suicide as a means of exerting pressure upon her, and that these letters were destroyed on being discovered after her death."[11]

Mendelssohn was present at Lind's London debut in Robert le Diable, and his friend, the critic H. F. Chorley, who was with him, wrote "I see as I write the smile with which Mendelssohn, whose enjoyment of Mdlle. Lind's talent was unlimited, turned round and looked at me, as if a load of anxiety had been taken off his mind. His attachment to Mademoiselle Lind's genius as a singer was unbounded, as was his desire for her success".[12] Mendelssohn worked with Lind on many occasions and wrote the beginnings of an opera, Lorelei, for her, based on the legend of the Lorelei Rhine maidens; the opera was unfinished at his death. He included a high F sharp in his oratorio Elijah ("Hear Ye Israel") with Lind's voice in mind.[13]

Four months after her London debut, she was devastated by the premature death of Mendelssohn in November 1847. She did not at first feel able to sing the soprano part in Elijah, which he had written for her. She finally did so at a performance in London's Exeter Hall in late 1848, which raised £1,000 to fund a musical scholarship as a memorial to him; it was her first appearance in oratorio.[14] The original intention had been to found a school of music in Mendelssohn's name in Leipzig, but there was not enough support for that in Leipzig, and with the help of Sir George Smart, Julius Benedict and others, Lind eventually raised enough money to fund a scholarship "to receive pupils of all nations and promote their musical training".[14] The first recipient of the Mendelssohn Scholarship was the 14-year-old Arthur Sullivan, whom Lind encouraged in his career.[1]

American tour

In 1849, Lind was approached by the American showman P.T. Barnum with a proposal to tour throughout the United States for more than a year. Realising that this would yield large sums for her favoured charities, particularly the endowment of free schools in her native Sweden, Lind agreed. Her financial demands were stringent, but Barnum met them, and in 1850 they reached agreement.[3]

Together with a supporting baritone, Giovanni Belletti, and her London colleague Julius Benedict as pianist, arranger and conductor, Lind sailed to America in September 1850. Barnum's advance publicity made her a celebrity even before she arrived in the U.S., and she received a wild reception on arriving in New York. Tickets for some of her concerts were in such demand that Barnum sold them by auction. The enthusiasm of the public was so strong that the American press coined the term "Lind mania".[15]

After New York, Lind's party toured the east coast of America, with continued success, and later took in Cuba, the southern states of the U.S., and Canada. By early 1851, Lind had become uncomfortable with Barnum's relentless marketing of the tour, and she invoked a contractual right to sever her ties with him; they parted amicably. She continued the tour for nearly a year, under her own management, until May 1852. Benedict left the party in 1851 to return to England, and Lind invited Otto Goldschmidt to replace him as pianist and conductor.[3] Lind and Goldschmidt were married on February 5, 1852, near the end of the tour, in Boston. She took the name "Jenny Lind-Goldschmidt" both privately and professionally.

Details of the later concerts under her own management are scarce,[3] but it is known that under Barnum's management Lind gave 93 concerts in America; for these, she earned about $350,000, and he netted at least $500,000[16] ($9.97 million and $14.2 million, as of 2015, respectively).[17] She donated her profits to her chosen charities, including some U.S. charities.[3][18]

Later years

Lind and Goldschmidt returned to Europe together in May 1852. They lived first in Dresden, Germany, and, from 1855, in England for the rest of their lives.[3] They had three children: Otto, born September 1853 in Germany, Jenny, born March 1857 in England, and Ernest, born January 1861 in England.[1]

Although she refused all requests to appear in opera after her return to Europe, Lind continued to perform in the concert hall. In 1856, at the invitation of the Philharmonic Society conducted by William Sterndale Bennett she sang the chief soprano part in the first English performance of the cantata Paradise and the Peri by Robert Schumann.[19] In 1866, she gave a concert with Arthur Sullivan at St James's Hall. The Times reported, "there is magic still in that voice ... the most perfect singing – perfect alike in expression and in vocalization. ... Nothing more engaging, nothing more earnest, nothing more dramatic can be imagined."[20] At Düsseldorf in January 1870, she sang in "Ruth", an oratorio composed by her husband.[1] When Goldschmidt formed the Bach Choir in 1875, Lind trained the soprano choristers for the first English performance of Bach's B minor Mass, in April 1876, and performed in the mass.[21] Her concerts decreased in frequency until she retired from singing in 1883.[3]

In 1879–1887 Lind worked with Frederick Niecks on his biography of Chopin.[22] In 1882, she was appointed professor of singing at the newly founded Royal College of Music. She believed in an all-round musical training for her pupils, insisting that, in addition to their vocal studies, they were instructed in solfège, piano, harmony, diction, deportment and at least one foreign language.[23]

She lived her final years at Wynd's Point, Herefordshire, on the Malvern Hills near the British Camp. Her last public appearance was at a charity concert at Royal Malvern Spa in 1883.[1] She died, aged 67, at Wynd's Point on 2 November 1887 and was buried in the Great Malvern Cemetery to the music of Chopin's Funeral March. She bequeathed a considerable part of her wealth to help poor Protestant students in Sweden receive an education.[1]

Reputation, legacy and memorials

Critical reputation

.jpg)

There are no recordings of Lind's voice. She is believed to have made an early phonograph recording for Thomas Edison, but in the words of the critic Philip L. Miller, "Even had the fabled Edison cylinder survived, it would have been too primitive, and she too long retired, to tell us much".[24] The biographer Francis Rogers concludes that although Lind was much admired by Meyerbeer, Mendelssohn, the Schumanns, Berlioz and others, "In voice and in dramatic talent she was undoubtedly inferior to her predecessors, Malibran and Pasta, and to her contemporaries, Sontag and Grisi."[3] He notes that because of her expert promoters, including Barnum, "almost all that was written about her was undoubtedly biased by an almost overwhelming propaganda in her favor, bought and paid for".[3] Rogers says of Mendelssohn and Lind's other admirers, that their tastes were "essentially Teutonic" and, except for Meyerbeer, they were not expert in Italian opera, Lind's early specialty. He quotes a critic of the New York Herald, who noted "little deficiencies in execution, in ascending the scale, which even enthusiasm cannot deprive of their sharpness".[3] The American press agreed that Lind's presentation was more typical of Germanic "cold, untouching, icy purity of tone and style", rather than the passionate expression necessary for Italian opera, and the Herald wrote that her style was "suited to please the people of our cold climate. She will have triumphs here that would never attend her progress through France or Italy".[3]

The critic H. F. Chorley, who admired Lind, described her voice as having "two octaves in compass – from D to D – having a higher possible note or two, available on rare occasions;[n 1] and that the lower half of the register and the upper one were of two distinct qualities. The former was not strong – veiled, if not husky; and apt to be out of tune. The latter was rich, brilliant and powerful – finest in its highest portions."[25] Chorley praised her breath management, her use of pianissimo, her taste in ornament and her intelligent use of technique to conceal the differences between her upper and lower registers. He thought her "execution was great" and that she was a "skilled and careful musician", but felt that "many of her effects on the stage appeared overcalculated" and that singing in foreign languages impeded her ability to give expression to the text. He felt, however, that her concert singing was more admirable than her operatic performances, although he praised some of her roles.[3][n 2] Chorley judged her finest work to be in the German repertoire, citing Mozart, Haydn and Mendelssohn's Elijah as best suited to her.[25] Miller concluded that although connoisseurs of the voice preferred other singers, her wider appeal to the public at large was not merely a legend created by Barnum, but was a mixture of "a uniquely pure (some called it celestial) quality in her voice, consistent with her well-known generosity and charity."[24]

Memorials

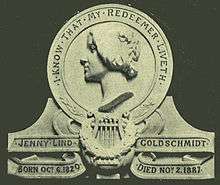

Under the name "Jenny Lind-Goldschmidt", she is commemorated in Poets' Corner, Westminster Abbey, London. Among those present at the memorial's unveiling ceremony on 20 April 1894 were Goldschmidt, members of the Royal Family, Sullivan, Sir George Grove and representatives of some of the charities supported by Lind.[26] There is also a plaque commemorating Lind in The Boltons, Kensington, London[27] and a blue plaque at 189 Old Brompton Road, London, SW7, which was erected in 1909.[28]

Lind has been commemorated in music, on screen, and even on banknotes. Both the 1996 and 2006 issues of the Swedish 50-krona banknote bear a portrait of Lind on the front. Many artistic works have honoured or featured her. Anton Wallerstein composed the "Jenny Lind Polka" around 1850.[29] In the 1930 Hollywood film A Lady's Morals, Grace Moore starred as Lind, with Wallace Beery as Barnum.[30] In 1941 Ilse Werner starred as Lind in the German-language musical biography film The Swedish Nightingale. In 2001, a semi-biographical film, Hans Christian Andersen: My Life as a Fairytale, featured Flora Montgomery as Lind. In 2005, Elvis Costello announced that he was writing an opera about Lind, called The Secret Arias with some lyrics by Andersen.[31] A 2010 BBC television documentary "Chopin – The Women Behind the Music" includes discussion of Chopin's last years, during which Lind "so affected" the composer.[32]

Many places and objects have been named for Lind, including Jenny Lind Island in Canada, the Jenny Lind locomotive and a clipper ship, the USS Nightingale. An Australian schooner was named Jenny Lind in her honour. In 1857 it was wrecked in a creek on the Queensland coast; the creek was accordingly named Jenny Lind Creek.[33]

In Britain, Goldschmidt's endowment of an infirmary for children in her memory in Norwich is perpetuated in its present form as the Jenny Lind Children's Hospital of the Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital.[34] There is a Jenny Lind Park in the same city.[35] A chapel is named for Lind at the University of Worcester City Campus[36] and in Andover, Illinois.[37] A hotel and pub is named after her in the Old Town of Hastings, East Sussex.[38] Hereford County Hospital has a psychiatric ward named for Jenny Lind.[39] A district in Glasgow is named after her.[40]

In the U.S., Lind is commemorated by street names in Fort Smith, Arkansas; New Bedford, Massachusetts; Taunton, Massachusetts; McKeesport, Pennsylvania; North Easton, Massachusetts; North Highlands, California and Stanhope, New Jersey; and in the name of the gold-rush town of Jenny Lind, California. An elementary school in Minneapolis, Minnesota is named after her.[41] She has been honoured since 1948 by the Barnum Festival, which takes place each June and July in Bridgeport, Connecticut. Through a national competition, the festival selects a soprano as the Jenny Lind winner. Her Swedish counterpart, chosen by the Royal Swedish Academy of Music and the People's Parks and Community Centre in Stockholm, visits during the festival, and the two perform several concerts together. In July, the American Jenny Lind winner traditionally travels to Sweden for a similar joint concert tour.

A bronze statue of a seated Jenny Lind by Erik Rafael-Rådberg, dedicated in 1924, sits in the Framnäs section of Djurgården island in Stockholm (at 59°19′45″N 18°6′8″E / 59.32917°N 18.10222°E).[42][43]

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ Note, however, the discussion above, regarding Mendelssohn's writing high F sharp specifically for her capabilities. Rogers quotes Chorley as follows: "In a song from Beatrice di Tenda which she adopted, there was a chromatic cadence, ascending to E in altissimo, and descending to the note whence it had risen, which could not be paragoned, of late days, as an evidence of mastery and accomplishment."

- ↑ Chorley wrote of Lind's concerts: "The wild, queer, Northern tunes brought here by her – her careful expression of some of Mozart's great airs – her mastery over such a piece of execution as "The Bird Song" in Haydn's Creation – and lastly, the grandeur of inspiration with which the "Sanctus" of angels in Mendelssohn's Elijah was led by her (the culminating point in the Oratorio) – are so many things to leave on the mind of all who have heard them".

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Rosen, "Lind, Jenny (1820–1887)"

- 1 2 3 4 5 Mdlle. Jenny Lind, The Illustrated London News, 24 April 1847, p. 272

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Rogers, Francis. "Jenny Lind", The Musical Quarterly, Vol. 32, No. 3 (July 1946), pp. 437–448 (subscription required)

- 1 2 Hetsch, Gustav and Theodore Baker. "Hans Christian Andersen's Interest in Music", The Musical Quarterly, Vol. 16, No. 3 (July 1930), pp. 322–329 (subscription required)

- ↑ Rogers, Francis. The Musical Quarterly, Vol. 32, No. 3 (Jul., 1946), p. 439; Nelson, Lars P. "Jenny Lind", What Has Sweden Done for the United States? (1903), p. 21

- ↑ Holland, Henry Scott; William Rockstro; William Smyth; Otto Goldschmidt, Memoir of Madame Jenny Lind-Goldschmidt her early art-life and dramatic career 1820–1851, Volume 1, pp. 204 and 338–40

- ↑ "Her Majesty's Theatre – First Appearance of Mademoiselle Jenny Lind, The Times, 5 May 1847, p. 5

- ↑ "Her Majesty's Theatre", The Times, 23 July 1847, p. 5

- ↑ "Her Majesty's Theatre", The Times, 11 May 1849, p. 8

- ↑ Duchen, Jessica. "Conspiracy of Silence: Could the Release of Secret Documents Shatter Felix Mendelssohn's Reputation?", published in The Independent, 12 January 2009. (Retrieved 4 August 2014)

- ↑ Biddlecombe (2013), 83.

- ↑ Chorley, p. 194

- ↑ "Mendelssohn's 200th Birthday," Performance Today, 3 February 2009. Hour 2, 36:00–42:00.

- 1 2 Sanders, L. G. D. "Jenny Lind, Sullivan and the Mendelssohn Scholarship", The Musical Times, September 1956, pp. 466–467 (subscription required)

- ↑ Linkon, Sherry Lee. "Reading Lind Mania: Print Culture and the Construction of Nineteenth-Century Audiences", Book History, Vol. 1 (1998), pp. 94–106 (subscription required)

- ↑ "America", The Times, 28 June 1851, p. 5

- ↑ Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Community Development Project. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Retrieved October 21, 2016.

- ↑ "Jenny Lind's Progress in America", The Observer, 6 October 1850, p. 3

- ↑ First Philharmonic by Cyril Ehrlich p. 103

- ↑ Review in The Times, 13 July 1866, accessed 22 December 2009

- ↑ Elkin, p. 62

- ↑ Lind apparently commissioned Félix Barrias's painting "La mort de Chopin", 1885 (Czartoryski Museum, Krakow): see Icons of Europe's essay, Why did Niecks write Chopin’s biography? submitted in December 2004 to Chopin in the World

- ↑ Lind-Goldschmidt, Jenny. "Jenny Lind and the R. C. M.", The Musical Times, November 1920, pp. 738–739 (subscription required)

- 1 2 Miller, Philip L. "Review", American Music, Vol. 1, No. 1 (Spring, 1983), pp. 78–80

- 1 2 Chorley, H. F., quoted in Rogers

- ↑ "Jenny Lind Memorial", The Times, 21 April 1894, p. 14

- ↑ The plaque can be seen here

- ↑ "Blue Plaques". English Heritage, accessed 16 June 2011

- ↑ "Jenny Lind Polka", British Library integrated catalogue, accessed 16 June 2011

- ↑ The New York Times, "A Lady's Morals a.k.a Jenny Lind" and Mordant Hall, "The Swedish Nightingale," The New York Times, 8 November 1930.

- ↑ Watson, Joanne. "The Secret Arias, Opera House, Copenhagen", The Independent, 11 October 2005

- ↑ Rhodes, James. "Chopin – The Women Behind The Music", BBC Four, BBC Programme info, 15 October 2010

- ↑ "Jenny Lind Creek", Beachsafe, accessed 26 January 2011

- ↑ "Jenny Lind Children's Hospital", Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital, accessed 18 June 2011

- ↑ "Jenny Lind Park", Norwich City Council, accessed 18 June 2011

- ↑ "Fundraising Campaign Launched for Stained Glass Window at Former Hospital", University of Worcester, accessed 18 June 2011

- ↑ Jenny Lind Chapel, Helios.augustana.edu, 4 January 2016

- ↑ "A hot time in the Old Town", The Jenny Lind Inn, accessed 18 June 2011

- ↑ "David Craig who left roadie job to become mental health nurse retires", Hereford Times, 10 February 2011

- ↑ "Glasgow Population and Size", Glasgow Guide Organisation, accessed 28 September 2016

- ↑ "Jenny Lind Elementary School", Minneapolis Public Schools, 29 January 2014

- ↑ "Lind-Goldschmidt, Jenny M.". Nordisk familjebok (Nordic Family Book) (in Swedish). 37 (Supplement L-to-Parliamentary) (2nd ("Owl") edition supplement ed.). Stockholm. 1925. p. 210. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

En sittande bronsstaty öfver henne, mod. af E. Rafael-Rådberg, aftäcktes 11 maj 1924 vid Framnäs på k. Djurgården, Stockholm.

(Swedish) - ↑ "Portrait Bust of Paul Engdahl by Rafael Radberg", 1stDibs, accessed 1 April 2014

Sources

- Biddlecombe, George (2013). "Secret Letters and a Missing Memorandum: New Light on the Personal Relationship between Felix Mendelssohn and Jenny Lind", in Journal of the Royal Musical Association, Volume 138, Issue 1, 2013, pp. 47–83.

- Brown, Clive (2003). A Portrait of Mendelssohn. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-09539-5.

- Chorley, Henry F (1926). Ernest Newman, ed. Thirty Years' Musical Recollections. New York and London: Knopf. OCLC 347491.

- Elkins, Robert (1944). Queen's Hall 1893–1941. London: Ryder. OCLC 604598020.

- Goldschmidt, Otto; Scott Holland, Henry; Rockstro (eds), W. S. (1891). Jenny Lind the artist, 1820–1851. A memoir of Madame Jenny Lind Goldschmidt, her art-life and dramatic career. London: John Murray. OCLC 223031312.

- Jorgensen, Cecilia; Jens Jorgensen (2003). Chopin and The Swedish Nightingale. Brussels: Icons of Europe. ISBN 2-9600385-0-9.

- Mercer-Taylor, Peter (2000). The Life of Mendelssohn. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-63972-7.

- Rosen, Carole (2004). Matthew, H. C. G.; Harrison, Brian, eds. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198614111.

Further reading

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Lind, Jenny. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Bulman, Joan (1956). Jenny Lind: a biography. London: Barrie. OCLC 252091695.

- Kielty, Bernadine (1959). Jenny Lind Sang Here. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 617750.

- Kyle, Elisabeth (1964). The Swedish Nightingale: Jenny Lind. New York: Holt Rinehart and Winston. OCLC 884670.

- Maude, Jenny M. C. (1926). The life of Jenny Lind, briefly told by her daughter, Mrs. Raymond Maude, O. B. E. London: Cassell. OCLC 403731797.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jenny Lind. |

- JennyLind.org website

- Profile of and links to information about Jenny Lind, the Barnum's American History Museum site

- Currier & Ives print of the First Appearance of Jenny Lind in America

- Profile of Lind at Scandinavian.wisc.edu

- The Jenny Lind Tower on Cape Cod

- Boyette, Patsy M. "Jenny Lind Sang Under This Tree", Olde Kinston Gazette, Kinstonpress.com (March 1999)

"Lind-Goldschmidt, Jenny". Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. 1892.

"Lind-Goldschmidt, Jenny". Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. 1892. "Lind, Jenny". Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.

"Lind, Jenny". Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.- Photo of 1924 statue of Lind in Stockholm, Sweden

- Lind and Chopin at World of Opera website

- Works by or about Jenny Lind at Internet Archive

- Jenny Lind: Her Life, Her Struggles and Her Triumphs by G. G. Rosenberg (1850)

- Lind's Memoirs (1820–1851)

- Biography by N. Parker Willis (1951)