Jing Hao

| Jing Hao | |

|---|---|

| Born |

c.855 Qinshui, Shanxi, China |

| Died | 915 |

| Known for | Painting |

| Movement | Northern Landscape style |

Jing Hao (Wade–Giles: Ching Hao, also known as Hongguzi) (c. 855-915)[1] was a Chinese landscape painter and theorist of the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period in Northern China. As an artist, he is often cited along with his pupil, Guan Tong, as one of the most critical figures in the development of the style of monumental landscape painting which appeared near the end of the Five Dynasties period. Later this style would come to be known as the Northern Landscape style; it strongly influenced the tradition of Northern Song painters. As a theorist, he is the person most responsible for codifying the theories underlying the work of later painters, and his treatises on painting and aesthetics continued to serve as textbooks for Northern Song artists more than a century after his death.

Life and career

Jing Hao began his artistic career during the later years of the Tang Dynasty. Initially he was influenced by the emphasis on monumental landscapes of Tang painters. Their goal to express the grandeur and harmony of nature was exemplified by the established masters such as Wang Wei. Following the collapse of the Tang, Northern China descended into a period of political chaos—the Five Dynasties—in which five separate ruling lines established themselves and were destroyed by factional infighting in rapid succession. An aversion to the turmoil of his era led Jing Hao to retire to seclusion in the northern Taihang Mountains. Here he spent the greater portion of his life in the pursuit of artistic development.

Taihang is an isolated region of dense cloud forests punctuated by jagged peaks. These unique geographical characteristics made the region particularly suited to Jing's developing interest in ink wash techniques. Jing was one of the earliest Chinese artists to employ ink washes (yongmo) to simulate depth and atmospheric perspective. Building on the approach initially pioneered by Tang painters such as Xiang Rong, Jing wrote that the principal aim of the yongmo technique was to “distinguish higher and lower [parts of objects] with a gradation in ink tones, and represent clearly shallowness and depth, making them appear natural as if they had not been done with a brush.” Of Xiang himself, Jing wrote that the earlier artist had “attained the secret of mysterious truth only through the use of ink wash”, but criticized Xiang for his lack of definition, lamenting that Xiang had “no bone in his brushwork”. Jing departed from such an approach by employing in his landscapes a mixture of atmospheric ink washes and bold brush strokes to accurately transcribe the Shanxi landscapes in which he worked. This technique, called cun fa, would characterize all of his major works as well as those of other artists who would study his work in later years.

In his writings, Jing described cun fa as a way of allowing the heart to follow after the brush. He wrote, “The image is to be seized without hesitation, so that the representation does not suffer. If the ink is too rich, it loses its expressive quality; if too weak in tone, it fails to achieve a proper vigour.” In other words, he sought to allow denser forms to take shape spontaneously out of the ink wash, like rocky crags jutting forth from misty basins. This embrace of spontaneity is readily apparent in his surviving works, such as Mount Lu.

Noted works

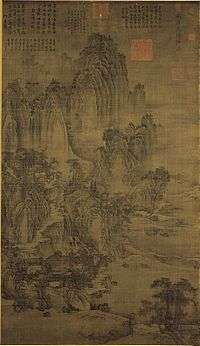

Despite his influence on the course of Northern Chinese painting, few works produced by Jing Hao have survived to the present day, and those that have are in poor condition. The piece most frequently held as a template of his style is Mount Lu, an ink painting on silk scroll which gives a rather fantastical rendering of one of Jiangxi's natural landmarks.[2] The work is a tight, vertical composition, employing Jing's newly developed cun fa technique to compress the landscape into layers of jutting rock-pillars between chasms of mist. The enclosed space of the composition enhances the monumental characteristics of the mountain, which fills some 90% of the scroll. Humans and buildings, though drawn with remarkable realism in a manner that contrasts sharply against the atmospheric landscape surrounding, are reduced to an almost unnoticeable scale, clustered at the foot of the mountain at the very bottom of the scroll, further conveying the intimidating grandeur of the natural world over the transient activities of man. Scholars have noted, however, that the mist in Mount Lu plays only a minimal role compared with that seen in some of Jing's other works, being employed much more conservatively than is common for the artist—a fact which has led to some speculation among art historians that this particular work may represent a “reminiscence” during a later period in the artist's life.

Nelson-Atkins Museum

Aside from Mount Lu, only one other major surviving work bearing the signature of Jing Hao has survived into the present. Travellers in Snow-Covered Mountains was recovered during the excavation of a tomb, and is currently exhibited in the Nelson-Atkins Museum in Kansas City, Missouri. However, although archaeological evidence suggests that the painting does indeed date from the mid-10th century—a period overlapping Jing's productive years—some scholars have thrown its authorship into question. Despite the signature, a number of art historians, including Jonathan Hay of New York University's Institute of Fine Arts, consider the painting too “primitive” to have been produced by an artist of Jing's reputation. Therefore, the attribution of this work to Jing Hao remains a subject of academic dispute.

Bifa Ji

Although admired as an artist during his own time and beyond, Jing Hao achieved his greatest fame as a theoretician, and it was during his seclusion in the Taihang that Jing Hao produced what is perhaps his most lasting contribution to Chinese arts, a treatise on painting humbly titled Bifa Ji (“Notes on Brushwork”), which would provide the theoretical basis of the Northern Song school for more than a century to come.

In Bifa Ji, which is written as a narrative, Jing Hao's theories on art are presented in a fictional conversation he has with an old man he meets on a road while wandering in the mountains. The old man, a sage, gives the artist a lecture, in which he describes five underlying essentials of painting: the first is spirit, the second rhythm, the third thought, the fourth scenery, the fifth brush, and finally the sixth, ink. Art historians have pointed out that these are almost certainly intended as a counterargument to the “six principles” of the famous pre-Tang theoretician Xie He, which emphasized the technical basics of painting—brush strokes and the application of color. Jing Hao provides a more logical and analytical approach, by first establishing abstract concepts such as thought and rhythm and then proceeding, from those, to practical application.

After describing each of the six essentials in turn, the sage then takes a further step which will lay the foundation for the Northern Song school, by creating a distinction between hua (“likeness”, conveying the outward appearance of a thing) and shi (“substance”, conveying the inherent nature of a thing). He insists that the type of brushstroke used in a painting must correspond to the inner nature of the object being depicted—for example, rocks must be painted with broad, hard brush strokes, flowers with delicate, thin brush strokes, etc. In Bifa Ji, Jing argues that an artist must strive to find a delicate balance between communicating the physical resemblance of an object, and conveying the emotional character it possesses—or, in the words of historian Michael Sullivan, an artist must strive for harmony between form and spirit. The search for such a balance between the real and the abstract would form the basis of Chinese art criticism for centuries to come.

Influence on later artists

Jing Hao's theories on art provided the foundation for much of what was to come during the later Song Dynasty. Most obvious is his influence on his pupil, Guan Tong, who spent many years studying with Jing in the mountains of Shanxi Province, and who later expanded upon his theories of hua and shi by extending the concepts not only to landscapes, but to seasons, animals and people as well. In the early 17th century, noted Ming art historian Dong Qichang classified Jing Hao and Guan Tong as the two founders of the Northern Landscape style, juxtaposed against the two founders of the southern school, Dong Yuan and Juran, who developed their theories at the same time.[3] Indeed, the two pairs were close enough that they are often referred to simply as “Jing-Guan” and “Dong-Ju” respectively. But Jing's fame was also apparent in his own era, as his work continued to be studied by Song artists such as Fan Kuan—who, like Jing, retreated into solitude and spent the last years of his life in the Shangxi mountains in order to be closer to nature.

See also

- Xie He

- Xiang Rong

- Li Cheng

- Fan Kuan

- Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period

- Culture of the Song Dynasty

- Tang Dynasty painting

- Ink and wash painting

- List of Chinese painters

- Chinese art

- History of Chinese art

Notes

- ↑ Barnhart, pg. 93.

- ↑ Some scholars debate whether ths work was actually painted by Jing Hao - Barnhart, pg. 93.

- ↑ "Jing Hao and Guan Tong"

References

- Barnhardt, Richard M.; Xin, Yang; Congzheng, Nie; Chaill, James; Shaojun, Lang; Wu, Hung (2002). Three Thousand Years of Chinese Painting. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09447-7, ISBN 978-0-300-09447-3 (Paperback).

- Hay, Jonathan (2008). Travellers in Snow-Covered Mountains: A Reassessment. Orientations Magazine. Volume 39, Number 8. November/December 2008. Hong Kong.

- Sullivan, Michael (1999). The Arts of China. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520218765 (Paperback).

- Watson, William (2003). The Arts of China 900-1620. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09835-9, ISBN 978-0-300-09835-8 (Paperback).

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Paintings from China. |