Julia Pastrana

| Julia Pastrana | |

|---|---|

|

Julia Pastrana, image from a 1900 book, showing her embalmed remains | |

| Born |

1834 Sinaloa, Mexico |

| Died |

25 March 1860 (age 26) Moscow, Russian Empire |

| Cause of death | Metro-peritonitis puerperalis |

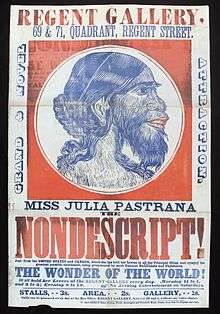

| Other names | Bear Woman, The Apewoman, The Nondescript |

| Height | 4 ft 5 in (1.35 m) |

| Spouse(s) | Theodore Lent (m. 1855) |

| Children | 1 son |

Julia Pastrana (1834 – 25 March 1860) was a performer and singer during the 19th century. Pastrana, an indigenous woman from Mexico, was born in 1834, somewhere in the state of Sinaloa.[1] She was born with a genetic condition, hypertrichosis terminalis (or generalized hypertrichosis lanuginosa[2]); her face and body were covered with straight black hair. Her ears and nose were unusually large, and her teeth were irregular. The latter condition was caused by a rare disease, undiagnosed in her lifetime, Gingival hyperplasia, which thickened her lips and gums.[2]

Life and career

Pastrana was raised in the household of Pedro Sanchez who served for a year as governor of Sinaloa.[3] According to Ireneo Paz, Francisco Sepúlveda, a customs official in Mazatlán, purchased Pastrana and brought her to the United States.[4] At first, Pastrana performed under the management of J.W. Beach, but in 1854, she eloped with Theodore Lent, marrying him in Baltimore, Maryland.[5] Lent took over her management, and they toured throughout the U.S. and Europe. Pastrana was advertised as a hybrid between an ape and a human, and as a "Bear Woman". However, during her performances, she illustrated her intelligence and talent: singing, dancing, and interacting with the audience.[6]

During a tour in Moscow, Pastrana gave birth to a baby with features similar to her own. The child survived only three days, and Pastrana died of postpartum complications five days later.

Medical examinations

During her life, Pastrana's management arranged to have her examined by doctors and scientists, using their evaluations in advertisements to attract a larger audience. These examinations were intrusive and inhumane. One doctor, Alexander B. Mott, M.D., certified that she was specifically the result of the mating of a human and an "Orang hutan".[7] Another, Dr. S. Brainerd of Cleveland, declared that she was of a "distinct species".[8] Francis Buckland stated that she was "only a deformed Mexican Indian woman".[8] However, Samuel Kneeland, Jr., a comparative anatomist of the Boston Society of Natural History, declared that she was human and of Indian descent.[9]

Charles Darwin discussed her case after her death, describing her as follows: "Julia Pastrana, a Spanish dancer, was a remarkably fine woman, but she had a thick masculine beard and a hairy forehead; she was photographed, and her stuffed skin was exhibited as a show; but what concerns us is, that she had in both the upper and lower jaw an irregular double set of teeth, one row being placed within the other, of which Dr. Purland took a cast. From the redundancy of the teeth her mouth projected, and her face had a gorilla-like appearance".[10]

After death

After Pastrana's death, her husband contacted Professor Sukolov of Moscow University, had his wife and son mummified, and displayed them in a glass cabinet. He later found another woman with similar features, married her and named her Zenora Pastrana, becoming wealthy from her exhibition. Some sources claim that he was eventually committed to a Russian mental institution in 1884 where he died.

The bodies of Pastrana and her son disappeared from the public view. They appeared in Norway in 1921 and were on display until the 1970s, when an outcry arose over a proposed tour of the USA and they were withdrawn from public view. Vandals broke into the storage facility in August 1976 and mutilated the baby's mummy. The remains were consumed by mice. Julia's mummy was stolen in 1979, but stored at the Oslo Forensic Institute after the body was reported to police but not identified. It was identified in 1990 and has rested in a sealed coffin at the Department of Anatomy, Oslo University since 1997. In 1994, the Norway Senate recommended burying her remains, but the Minister of Sciences decided to keep them, so scientists could perform research. A special permit was required to gain access to her remains.[1]

On 2 August 2012 it was reported in Aftenposten that Pastrana would finally be buried in Mexico at an unspecified date.[11] In February 2013, with the help of Sinaloa state governor Mario López Valdez, New York-based visual artist Laura Anderson Barbata,[12] Norwegian authorities, and others, the body was turned over to the government of Sinaloa and her burial was planned.[2] On 12 February 2013, hundreds of people attended her Catholic funeral, and her remains were buried in a cemetery in Sinaloa de Leyva, a town near her birthplace.[13]

Theater

A musical Pastrana by Australian writers Allan McFadden and Peter Northwood was performed by Melbourne's Church Theatre in 1989.[14][15] The production was nominated for five Melbourne Green Room Awards.

A play based on Pastrana's life, The True History of the Tragic Life and Triumphant Death of Julia Pastrana, the Ugliest Woman in the World (1998) was written by Shaun Prendergast. A 2003 Texas production of the play staged by Kathleen Anderson Culebro, sister of Laura Anderson Barbato, led to the campaign by Barbato to repatriate Pastrana's remains from Norway to Mexico.[2]

Film

Marco Ferreri's film The Ape Woman (1964) is based on Pastrana's life story.

On 14 October 2013 the in-development movie "Velvet" was announced, based upon the life and experiences of Julia Pastrana, and from an original screenplay by Celso García and Francisco Payó González. "Velvet" is directed by Celso García and is an international production with the support of various personalities behind and in front of the camera. The announcement appeared in an article published in Mexican newspaper "Mural", member of the editorial group Reforma.

Music

The Ass Ponys wrote and recorded the song Julia Pastrana about her life on their 1993 album Grim.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Julia Pastrana. |

- Alice Elizabeth Doherty, "The Minnesota Woolly Girl"

- Annie Jones, "The Bearded Woman"

Notes

- 1 2 Lerma Garay, Antonio. Érase una vez en Mazatlán. Comisión para la Celebración del Bicentenario de la Independencia y Centenario de la Revolución. Culiacán. 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 Wilson, Charles (February 11, 2013). "An Artist Finds a Dignified Ending for an Ugly Story". New York Times. Retrieved February 11, 2013

- ↑ Julia Pastrana: Brief Chronologyhttp://www.lauraandersonbarbata.com/work/mx-lab/julia-pastrana/3.php

- ↑ Ireneo Paz, Algunas Compañas,' p. 239'

- ↑ The Sun: Nov. 10, 1855; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Baltimore Sun, The (1837-1987) pg. 1

- ↑ http://www.lauraandersonbarbata.com/work/mx-lab/julia-pastrana/3.php

- ↑ Bondeson, Jan (1997). "The strange story of Julia Pastrana". A Cabinet of Medical Curiosities. I.B.Tauris. p. 219. ISBN 1860642284.

- 1 2 Buckland, F.T. (1865). Curiosities of Natural History, Vol. 2. London: Bentley. pp. 44–51.

- ↑ Born Different, p. 81

- ↑ Darwin, Charles, The Variation of Animals and Plants Under Domestication, Vol. II. John Murray, London, 1868. p. 328

- ↑ "Hun ble vist frem som "apekvinne". Nå skal Julia Pastrana endelig begraves". Aftenposten.

- ↑ "Julia Pastrana". www.lauraandersonbarbata.com. Retrieved 2016-11-17.

- ↑ Stargardter, Gabriel (13 Feb 2013). "'Ugliest woman in the world' buried 150 years after end of tragic life". msn.news. Reuters. Retrieved 26 Feb 2013.

- ↑ http://www.ausstage.edu.au/pages/event/1919

- ↑ Radic, Leonard (4 August 1989). "Roll up, roll up, and see the bearded lady". The Age. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

References

- Bartra, Roger. “El trágico viaje de una mujer salvaje mexicana al mundo civilizado”. Istor 64 (2016): 179-198. México.

- Gylseth, Christopher Hals; Lars O. Toverud (2003). Julia Pastrana: The Tragic Story of the Victorian Ape Woman. Sutton. ISBN 978-0-7509-3312-4. OCLC 52829869.

- Miles, A.E.W. (February 1974). "Julia Pastrana: The Bearded Lady". Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine. 67 (2): 160–164. PMC 1645262

. PMID 4595237.

. PMID 4595237.

External links

- Behold! The Heartbreaking, Hair-Raising Tale Of Freak Show Star Julia Pastrana, Mexico’s Monkey Woman

- JULIA PASTRANA - The Nondescript