Kārlis Ulmanis

| Kārlis Ulmanis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Prime Minister of Latvia | |

|

In office November 19, 1918 – June 18, 1921 | |

| President | Jānis Čakste |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Zigfrīds Anna Meierovics |

|

In office December 24, 1925 – May 6, 1926 | |

| President | Jānis Čakste |

| Preceded by | Hugo Celmiņš |

| Succeeded by | Arturs Alberings |

|

In office March 27, 1931 – December 5, 1931 | |

| President | Alberts Kviesis |

| Preceded by | Hugo Celmiņš |

| Succeeded by | Marģers Skujenieks |

|

In office March 17, 1934 – June 17, 1940 | |

| President |

Alberts Kviesis Himself |

| Preceded by | Ādolfs Bļodnieks |

| Succeeded by | Augusts Kirhenšteins |

| 4th President of Latvia* | |

|

In office April 11, 1936 – July 21, 1940 | |

| Prime Minister |

Himself Augusts Kirhenšteins |

| Preceded by | Alberts Kviesis |

| Succeeded by | Augusts Kirhenšteins as Prime minister |

| Foreign Minister of Latvia | |

|

In office May 4, 1926 – December 17, 1926 | |

| Prime Minister | Arturs Alberings |

| Preceded by | Hermanis Albats (Acting) |

| Succeeded by | Felikss Cielēns |

|

In office March 24, 1931 – December 4, 1931 | |

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Preceded by | Hugo Celmiņš |

| Succeeded by | Kārlis Zariņš |

|

In office March 17, 1934 – April 17, 1936 | |

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Preceded by | Voldemārs Salnais |

| Succeeded by | Vilhelms Munters |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

September 4, 1877 Bērze, Bērze Parish, Latvia (part of the Russian Empire) |

| Died |

September 20, 1942 (aged 65) Krasnovodsk, Soviet Union (now Türkmenbaşy, Turkmenistan) |

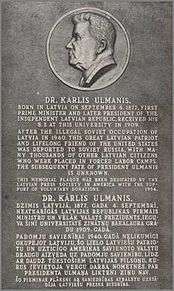

| Resting place | Unknown |

| Nationality | Latvian |

| Political party | Latvian Farmers' Union (1917–1934) |

| Spouse(s) | None |

| Alma mater | University of Nebraska-Lincoln |

| Signature |

|

| *Self-proclaimed | |

Kārlis Augusts Vilhelms Ulmanis (September 4, 1877 in Bērze, Bērze Parish, Courland Governorate, Russian Empire – September 20, 1942 in Krasnovodsk prison, Soviet Union, now Türkmenbaşy, Turkmenistan) was one of the most prominent Latvian politicians of pre-World War II Latvia during the interwar period of independence from November 1918 to June 1940. The legacy of his dictatorship still divides public opinion in Latvia.

Education and early career

Born in a prosperous farming family, Ulmanis studied agriculture at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich and at Leipzig University. He then worked in Latvia as a writer, lecturer, and manager in agricultural positions. He was politically active during the 1905 Revolution, was briefly imprisoned in Pskov, and subsequently fled Latvia to avoid incarceration by the Russian authorities. During this period of exile, Ulmanis studied at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln in the United States, earning a Bachelor of Science degree in agriculture. After working briefly at that university as a lecturer, Ulmanis moved to Houston, Texas, where he had purchased a dairy business.[1]

Ulmanis returned to Latvia from American exile in 1913, after being informed that it was now safe for political exiles to return due to the declaration of a general amnesty by Nicholas II of Russia. This safety was short-lived as World War I broke out one year later and Courland Governorate was partially occupied by Germany in 1915.

Political career in independent Latvia

In the last stages of World War I, he founded the Latvian Farmers' Union, one of the two most prominent political parties in Latvia at that time. Ulmanis was one of the principal founders of the Latvian People's Council (Tautas Padome), which proclaimed Latvia's independence from Russia on November 18, 1918 with Ulmanis as the first Prime Minister. After the Latvian War of Independence of 1919 - 1920, a constitutional convention established Latvia as a parliamentary democracy in 1920. Ulmanis served as Prime Minister in several subsequent Latvian government administrations from 1918 to 1934.

The Coup of May 15, 1934

On the night from May 15 to May 16, 1934, Ulmanis as Prime Minister with the support of Minister of War Jānis Balodis proclaimed a State of War in Latvia and dissolved all political parties and Saeima (parliament). Ulmanis established executive non-parliamentary authoritarian rule where he ruled as the Prime Minister, and later as State President. The bloodless coup was carried out by army and units of the national guard Aizsargi loyal to Ulmanis. They moved against key government offices, communications and transportation facilities. Many elected officials and politicians (almost exclusively Social Democrats, as well as figures from the extreme right and left) were detained, as were any military officers that resisted the coup d'etat. Some 2,000 Social Democrats were initially detained by the authorities, including most of the Social Democratic members of the disbanded Saeima, as were members of various right-wing radical organisations, such as Pērkonkrusts.

In all, 369 Social Democrats, 95 members of Pērkonkrusts, pro-Nazi activists from the Baltic German community, and a handful of politicians from other parties were interned in a prison camp established in the Karosta district of Liepāja. After several Social Democrats, such as Bruno Kalniņš, had been cleared of weapons charges by the courts, most of those imprisoned began to be released over time.[2] Those convicted by the courts of treasonous acts, such as the leader of Pērkonkrusts Gustavs Celmiņš, remained behind bars for the duration of their sentences, three years in the case of Celmiņš.[3]

The incumbent State President Alberts Kviesis supported the coup and served out the rest of his term until April 11, 1936, after which Ulmanis assumed office of the State President, a move considered unconstitutional. In the absence of parliament, laws continued to be promulgated by the cabinet of ministers.

Authoritarian regime

The Ulmanis regime was unique among other European dictatorships of the interwar period. Ulmanis did not create a ruling party, rubber-stamp parliament or a new ideology. It was a personal, paternalistic dictatorship in which the leader claimed to do what he thought was best for Latvians. All political life was proscribed, culture and economy was eventually organized into a type of corporate statism made popular during those years by Mussolini. Chambers of Professions were created, similar to Chambers of Corporations in other dictatorships.

All political parties, including Ulmanis own Farmers' Union, were outlawed. Part of the constitution of the Latvian Republic and civil liberties were suspended. All newspapers owned by political parties or organisations were closed and all publications were subjected to censorship and government oversight by the Ministry of Public Affairs led by Alfrēds Bērziņš. The regime based its legitimacy on the founding myth of the war of independence. The army and the Aizsargi paramilitary were lavished with privileges.

Ulmanis is often believed to have been a popular leader especially among farmers and ethnic Latvians. This is debatable. Before his 1934 coup, his party gained only 12.2% of the popular vote in the Latvian parliamentary election, 1931, continuing a steady decline from the 1922 Constitutional convention, and an all-time low. Some historians believe that one of the chief motives for the coup was his fear of losing even more votes in the upcoming elections. From the time of his coup until his demise, for obvious reasons, no reliable voting or popularity statistics were available.

Ideology

Ulmanis was a Latvian nationalist, who espoused the slogan "Latvia for Latvians" which meant that Latvia was to be a Latvian nation state, not a multinational state with traditional Baltic German elites and Jewish entrepreneurial class. At the same time, the slogan "Latvia's sun shines equally over everyone" was used and no ethnicity was subjected to repressions. German, Jewish and other minority newspapers and organizations continued to exist as far as the limitations of authoritarian dictatorship permitted. Officially Ulmanis held that every ethnic community in Latvia should develop its own authentic national culture, instead of assimilating into Latvians, but the state's primary purpose is to help Latvians to become masters in their homeland. This was to be achieved by active state involvement in economy and greater emphasis on Latvian culture. Statistics were produced showing that the German, Jewish and Polish (in Latgale) minorities have too much power in economy and certain professions, thus preventing Latvians from achieving their full potential.

Latvianisation policies were followed in the area of education. During Ulmanis' rule, education was strongly emphasized and literacy rates in Latvia reached high levels. Especially in eastern Latvia Latgale region however, education was actively used as a tool of assimilation[4][5] of minorities. Many new schools were built, but they were Latvian schools and minority children were thus assimilated.

It is important to notice that while an absolute ruler, Ulmanis did not allow any physical violence or unlawful acts towards minorities and dealt harshly with right and left wing extremists, and with both Nazi and Communist sympathizers.[6] Between 1920 and 1939, many Jews escaping Soviet Russia and Nazi Germany found refuge in Latvia.

Economy

During his leadership Latvia recorded major economic achievements. The state assumed a larger role in the economy and state capitalism was introduced by purchasing and uniting smaller competing private companies into larger state enterprises. This process was controlled by Latvijas Kredītbanka, a state bank established in 1935. Many large-scale building projects were undertaken - new schools, administrative buildings, Ķegums Hydroelectric Power Station. Due to an application of the economics of comparative advantage, the United Kingdom and Germany became Latvia's major trade partners, while trade with the USSR was reduced. The economy, especially the agriculture and manufacturing sectors, were micromanaged to an extreme degree. Ulmanis nationalised many industries. This resulted in rapid economic growth, during which Latvia attained a very high standard of living. At a time when most of the world's economy was still suffering from the effects of the Great Depression, Latvia could point to increases in both gross national product (GNP) and in exports of Latvian goods overseas. This, however, came at the cost of liberty and civil rights.

The policy of Ulmanis, even before his accession to power, was openly directed toward eliminating the minority groups from economic life and of giving Latvians of Latvian ethnicity access to all positions in the national economy. This was sometimes referred to as "Lettisation".[7] According to some estimates, about 90% of the banks and credit establishments in Latvia were state owned or under Latvian management in 1939, against 20% in 1933. Alfrēds Birznieks, the minister of agriculture, in a speech delivered in Ventspils on January 26, 1936, said:

Latvian people are the only masters of this country; Latvians will themselves promulgate the laws and judge for themselves what justice is.[7]

As a result, the economic and cultural influence of minorities – Germans, Jews, Russians, Poles – declined.

Latvia's first full-length sound movie "Zvejnieka dēls" (Fishermans' Son) was a tale of young fisherman who tries to free other local fishermen from the power of a middleman and shows them that the future lies in cooperative work.[8] The movie was based on a widely popular novel written by Vilis Lācis who in 1940 became the Prime Minister of the Soviet occupied Latvian SSR.

Later life and death

On August 23, 1939, Adolf Hitler's Germany and Joseph Stalin's USSR signed a non-aggression agreement, known as the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, which contained a secret addendum (revealed only in 1945), dividing Eastern Europe into spheres of influence. Latvia was thereby assigned to the Soviet sphere. Following a Soviet ultimatum in October 1939, Ulmanis had to sign the Soviet–Latvian Mutual Assistance Treaty and allow Soviet military bases in Latvia. In June 17, 1940, Latvia was completely occupied by the Soviet Union. Ulmanis ordered Latvians to show no resistance to the Soviet Army, saying in his radio speech "I will remain in my place and you remain in yours".

For the next month Ulmanis cooperated with the Soviets. After Soviet controlled elections of July 14-15 a new parliament met and proclaimed a Soviet republic. On July 21, 1940 Ulmanis was forced to resign and asked the Soviet government for a pension and permission to emigrate to Switzerland. Instead, he was arrested and sent to Stavropol in Russia, where he worked in his original profession as Kolkhoz agronom for a year. After the start of German-Soviet war he was imprisoned in July 1941. A year later, as German armies were closing in on Stavropol, he and other inmates were evacuated to a prison in Krasnovodsk in present-day Turkmenistan. On the way there, he contracted dysentery and soon died on 20 September 1942. His grave site is unknown, but a small memorial site was built in Turkmenbashi cemetery.[9] Ulmanis had no wife or children, as he used to say that he was married to Latvia.

Later assessments

Kārlis Ulmanis's legacy for Latvia and Latvians is a complex one. In the postwar Latvian SSR the Soviet régime labeled Ulmanis a fascist, indistinguishable from the Nazis, accusing him of corruption and of bloody repressions against Latvian workers.[10] Ulmanis, in fact, had outlawed the fascist party and imprisoned its leader, Gustavs Celmiņš.

Among the postwar Latvian émigrés of Latvian cultural background in exile, Ulmanis was idealised by many of those who viewed his 6-year authoritarian rule as a Golden Age of the Latvian nation. Some traditions created by Ulmanis, such as the Draudzīgais aicinājums (charitable donations to one's former school), continued to be upheld.

In independent Latvia today, Ulmanis remains a popular, if also controversial figure. Many Latvians view him as a symbol of Latvia's independence in pre-World War II Latvia, and historians are generally in agreement about his positive early role as prime minister during the country's formative years. With regard to the authoritarian period, opinions diverge, however. On the one hand, it is possible to credit Ulmanis for the rise of ethnic Latvians' economic prosperity during the 1930s, and stress that under his rule there was not the same level of militarism or mass political oppression that characterized other dictatorships of the day. On the other hand, historians such as Ulmanis biographer Edgars Dunsdorfs are of the view that someone who disbanded Parliament and adopted authoritarian rule cannot be regarded as a positive figure, even if that rule was in some terms a prosperous one.[11]

One sign that Ulmanis was still very popular in Latvia during the first years of regained independence was the election of his grand-nephew Guntis Ulmanis as President of Latvia in 1993.

One of the major traffic routes in Riga, the capital of Latvia, is named after him (Kārļa Ulmaņa gatve, previously named after Ernst Thälmann). In 2003, a monument of Ulmanis was unveiled in a park in Riga centre.[12]

Ulmanis is depicted in a very positive light in the 2007 Latvian film Rigas Sargi (Defenders of Riga), which is based on the defense of Riga against Russo-German forces of West Russian Volunteer Army in 1919.[13]

See also

- Latvian War of Independence

- Freikorps in the Baltic

- Latvian Provisional Government

- Soviet occupation of Latvia in 1940

References

- ↑ Karlis Ulmanis: From University of Nebraska Graduate to President of Latvia

- ↑ Bērziņš, Valdis (ed.) (2003). 20. gadsimta Latvijas vēsture II: Neatkarīgā valsts 1918–1940 (in Latvian). Riga: Latvijas Vēstures institūta apgāds. ISBN 9984-601-18-8. OCLC 45570948.

- ↑ Kārlis Ulmanis Authoritarian Regime 1934-1940

- ↑ Horváth, István (2003). Minority politics within the Europe of regions. Bucharest: Editura ISPMN. ISBN 9789731970837.

- ↑ Purs, Aldis (2002). "The Price of Free Lunches: Making the Frontier Latvian in the Interwar Years" (PDF). The Global Review of Ethnopolitics.

- ↑ Centropa

- 1 2 The Jews of Latvia

- ↑ Zvejnieka dēls

- ↑ President visits Turkembashi's Christian Cemetery

- ↑ Concise Latvian SSR Encyclopedia

- ↑ LETA (15 May 2009). "Aprit 75 gadi kopš Kārļa Ulmaņa rīkotā valsts apvērsuma Latvijā" (in Latvian). Diena. Retrieved 15 May 2009.

- ↑ Monument to former Latvian President Kārlis Ulmanis

- ↑ Video on YouTube

External links

- (Latvian) Biography

- Documents obtained and donated by Paul Berkay and transcribed by Sherri Goldberg and Margaret Kannensohn

- Kārlis Ulmanis, Latvian, and Baltic History Collection at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln

- (Latvian) Biography by Edgars Dunsdorfs

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Position created |

Prime Minister of Latvia 1918-1921 |

Succeeded by Zigfrīds Anna Meierovics |

| Preceded by Hugo Celmiņš |

Prime Minister of Latvia 1925-1926 |

Succeeded by Arturs Alberings |

| Preceded by Alberts Kviesis |

President of Latvia 1936-1940 |

Succeeded by Augusts Kirhenšteins |