Keloid disorder

| Keloid disorder | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Bulky Keloid forming at the site of abdominal surgery | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| ICD-9-CM | 701.4 |

Keloid disorder results in very hard to treat fibro-proliferative cutaneous connective tissue secondary to dysregulation in various skin repair and healing processes in individuals who are genetically predisposed to this disorder.

Although reported in individuals from almost all ethnic backgrounds, the disorder is more common among two distinct and genetically distant populations; Africans / African Americans and Asians. The only groups of individuals who may be spared from developing keloids are albinos, making the case for a relationship between melanin production and susceptibility to keloid formation at least among dark-skinned individuals.

Keloid disorder has a very diverse phenotype and can present itself either as a single small spot on the skin of the affected individual, or often involving several areas of the skin. In some patients, keloid lesions can grow and form a large size skin tumor.

From the onset of development, each keloid lesion follows its own particular clinical course. Some patients develop only one keloid lesion which only grows to a particular size and it stops growing thereafter. Some patients can develop multiple lesions, on multiple sites of the body.

Lack of understanding of the disorder even reflects itself in terminology used to describe this illness. Terms such as "keloid scarring" or "keloid scars" that are commonly used, even by those who treat keloid patients. These terms do not properly describe this disorder, and erroneously apply a lesser importance to this genetic skin disorder. A genetic condition that results in formation of large skin tumors, or itching, pain and burning sensation, a condition that disables certain patients, and covers 20-30% of their skin, a condition that some treat it with radiation therapy, is not a condition of “skin scarring”. It is indeed a true skin disorder.

The National Institute of Health webpage on keloid states that “keloids often do not need treatment.”[1]

Terminology

Term “Keloid Disorder” applies to the disease entity itself, encompassing the whole aspect and various clinical presentation of the disorder.

Term “Keloid” is used interchangeably to describe the disease entity, or to refer to the individual keloid lesion.

Terms “Keloid Lesion” or “Keloidal Lesion” describe the actual skin lesions that is seen.

Term “Keloid Patient” is used to define an individual patient who is suffering from keloid disorder.

Term “Acne Keloidalis” of “Acne Keloidalis Nuchae” was described as a unique entity in 1800, to define the type of keloid disorder that presents itself in the occipital scalp or upper posterior neck. This entity is almost exclusively in Africans/African-American men.[2]

Term “Keloid Scar” or “Keloid Scarring” is an erroneous term, which is simply misleading, meaningless and non-descriptive of this medical condition and should not be used.

Signs and symptoms

Keloid disorder has a diverse phenotype. The disorder can present itself either as a single small spot on the skin of the affected individual, or it can involve several areas of the skin. In some cases, presentation is limited to one or a few small lesions of the skin, either round or linear; in other cases, keloid lesions can appear as large nodule, a conglomerate of nodules, massive skin tumors, or as very large keloid patches. Although benign, keloid can cause major aesthetic, and at time functional problems, all of which pose significant negative impact on the individual’s quality of the life.

Keloid disorder is characterized by excessive collagen and/or glycoprotein deposits in the dermis. There is, however, void of knowledge as to why in some case the keloid lesions are limited to one area of the skin, or they take on a particular shape and form.

In addition to having keloid lesion on the skin, some keloid patients also suffer from pruritus and burning sensation or pain at the site of their keloids. These symptoms are quite common among those who have chest wall keloids.

- Small size keloid papules

- Keloid Nodules (1–2 cm in diameter) and a keloid tumor >2 cm. in diameter.

- Two linear keloids

- Patch of Flat Keloid

- Butterfly type keloid.

- Guttate Keloid

- A very painful, hyper-inflammatory keloid of the chest wall.

Superficially Spreading Keloid

Superficially Spreading Keloid Pedunculated Keloid that grows with a stalk, much like a mushroom

Pedunculated Keloid that grows with a stalk, much like a mushroom- Bulky keloid.

Massive Keloids

Massive Keloids- Scalp Keloid in Occipital Area

- Earlobe Keloid

- Massive Earlobe Keloid forming after repeated surgeries.

- Posterior auricular Keloid triggered by otoplasty surgery.

- Facial Nodular Keloids in African American Male,

- Bulky Keloid of the Neck

- A very painful, inflammatory keloid of the chest wall, worsened with surgery.

- Flat, Superficially Spreading Keloid in Upper Arm Area.

Pedunculated Umblical Keloid.

Pedunculated Umblical Keloid.- Massive, Multi-Nodular Conglomerate of Pubic Area, worsened with surgery.

- Massive keloid in the sole of foot in a patient with massive keloids elsewhere.

- Pay attention to the well healed midline scar of surgery, and the keloid forming in the navel area following piercing.

- Keloid formation triggered by tattooing

Cause

Triggering factor for great majority of keloid patients is the wounding of the skin, which is inflicted in many different ways. It is however, against the backdrop of genetic susceptibility of the individual that a keloid forms at the site of skin injury.

Ear piercing is by far the leading cause of earlobe keloid formation in predisposed individuals. Ear piercing is a widespread practice, commonly performed by non-medical personnel in jewelry shops, stores and malls. Parents often choose to have their daughter’s earlobes be pierced at very early ages. Practice of ear piercing has never been subject of a scientific research.

Acne is perhaps the second most common triggering factor for development of keloid in genetically prone individuals. Acne induced keloids are often seen in the face, shoulders and the chest area.

Surgery and simple skin wounds from accidents can lead to keloid formation. Keloid patients, and those with a family history of keloid disorder should avoid undergoing esthetic surgery of any sort, simply because development and treatment of keloidal lesions that develop after a face lift, or after breast augmentation, is a daunting task.

Vaccination with BCG often leads to keloid formation at the site of vaccination.

Chicken pox, and other inflammatory skin condition can also trigger keloid formation.

Tattooing and Piercing practices often results in keloid formation in genetically prone individuals.

Genetics

Most people, especially Africans and African Americans have a positive family history of keloid disorder. Development of keloids among twins also lends credibility to existence of a genetic susceptibility to develop keloids. Marneros et al. (1) reported four sets of identical twins with keloids; Ramakrishnan et al.[3] also described a pair of twins who developed keloids at the same time after vaccination. Case series have reported clinically severe forms of keloids in individuals with a positive family history and black African ethnic origin.

Genetic basis of keloid disorder is poorly understood and is an area that has not been properly researched. While the mode of inheritance of keloid disorder in not known, several theories have been proposed, including autosomal recessive, autosomal dominant with incomplete penetrance and variable expression. Such a diverse phenotype is most likely associated with a complex and multigene inheritance with deletion or non-deletion single point mutations in more than one gene.

Unfortunately, we have no knowledge as to how the vast and varied phenotype of this disorder correlates to any particular genotype. This has been topic of several studies, none of which have provided solid evidence for any reproducible genetic abnormality.

The variable phenotype of the disease mimics a multi gene inheritance, with certain individuals perhaps having only one mutations or one genetic abnormality and present with one or very few keloid lesions, to those who have inherited two or more genetic mutations, whereby the disease appears in its most severe form. An analogy can be made to thalassemia, whereby various phenotypes; thalassemia traits, minor, inter-media and major; are linked to various genetic abnormalities involving two sets of alleles for alpha and beta globin genes and numerous genetic abnormalities of the two distinct genes. Much like thalassemia, keloid disorder with its clinical phenotype varying from almost asymptomatic to severe and very massive skin involvement, may indeed be a constellation of several monogenic conditions, each resulting in a particular phenotype. Much work needs to be done to better understand the genetic of this fascinating disorder.

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of keloid disorder is for most part unknown and poorly understood. Culprit in formation of keloid lesion is the wounding of the skin in genetically prone individual.

Disruption in the normal anatomy of the skin and subsequent genetically driven dysregulated wound healing, leads to formation of keloid lesions. Wound healing is a very complex and dynamic process that normally results in the restoration of anatomical continuity and function of the skin. Four distinct, yet overlapping phases of wound healing are hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation and remodeling.

A normal and balanced wound healing response results in minimal scar formation. Keloid formation on the other hand is due to uninhibited, excessive and protracted wound healing response to a dermal injury, as if the brakes in wound healing process are malfunctioning and the runaway car cannot stop. The result is excess fibroblast proliferation and collagen deposition that outgrows the original site of dermal injury.

Worsening of earlobe keloids after surgical excision, is most probably due to triggering of the same dysregulated wound healing mechanisms, yet to a new dermal injury that is more extensive in nature, than the original triggering injury, for instance from the ear piercing.

Another important factor in pathogenesis of keloid is age of onset of keloid, which peaks at puberty and early teens. It is therefore postulated that although the genetic predisposition is transmitted from parents to their children, in most cases, the actual disorder is not triggered until children reach puberty. Exception to this rule is development of keloids in very young children. The author, Michael H. Tirgan, MD, has treated a 21-year-old woman who developed right sided posterior earlobe keloid, many years after bilateral earlobe piercing, only after the earring she was wearing was ripped off her ear by an accidental force, resulting in a tear in her earlobe. Although she had both her ears pierced as a child, she only developed a keloid in the right ear after sustaining a new injury in her adult age.

Lane[4] reported that keloids are more likely to develop when ears are pierced after age 11 than before, even in patients with a family history of keloid. He recommended that patients with a family history of keloids should consider not having their ears pierced and if this is not an option, then piercing should be considered during early childhood, rather than later childhood. Although Lane’s conclusion holds true in great majority of patients, cases of keloid in children under age of 5 defies his proposed theory, and is a testament to the lack of our understanding of pathogenesis and genetics of keloid disorder.

As to why there is such latency in development of earlobe keloids, some have suggested that development of keloids may be stimulated by various hormonal changes at puberty or during pregnancy.

In addition to wounding of the skin in predisposed individuals; there must exist other factors that contribute to development of ear keloids. In his 1979 article, Pierce[5] raised a valid question as to why some patients with bilateral earlobe piecing only develop unilateral earlobe keloids. Thirty years later, we still don’t have answer to this probing question.

We can only assume that one ear suffers from a unique post piercing complication and develops a keloid, and the other ear is spared this complication. Could it be local infection in one ear? Certainly some patients report this as the culprit to development of keloid. Could it be unequal tissue injury in the ears? Could it be sustaining a future injury to the earlobe as a result of wounding of one earlobe while the earring pin passes through the earlobe while wearing the earring? We can hypothesize about many other causes. Which one is correct? More than thirty years later, we have not made any progress in answering this very basic question.

A more plausible theory, based on clinical observation of author Michael H. Tirgan is that perhaps, if we had a method of mapping the distribution pattern of the genetic abnormality in keloid patients, each patient’s skin will have a unique map that will determine where the keloid will form.

It is therefore possible, that in genetically predisposed patients, certain parts of their skin, upon infliction of an injury, will develop a keloid, while other parts of skin may not. One of the images posted here depict a particular patient, in whom the midline abdominal incision healed well, free of keloid or even hypertrophic scarring. On the other hand, same patient developed a keloid at the site of piercing of her navel, supporting the theory that although she is prone to develop keloids, this predisposition is limited to certain parts of the skin. Furthermore, the proposed genetic skin map has a tendency to change over time and either shrink, or often expand to wider areas of the skin.

Classification

Morphological

Keloid lesions take on a variety of shapes and forms, and appear in any part of the skin. Keloid lesions can be classified according to their appearance.

“Keloidal Papules” refers to a small, and often newly formed keloid lesions. These lesions are solid, raised above the level of skin and have distinct borders and measure from few millimeters up to one centimeter in diameter. All keloids start with a small papule. In rare patients, keloid lesions can be very few in number, and very small in size. This pattern is often encountered in the upper chest area.

“Nodular Keloid” lesions appear round, are raised from the surface of the skin, and often feel like a hard lump in skin, appearing as half of a sphere with a broad base. These lesions are solid, round or oval, raised above the level of skin and have distinct borders and measure from 1-2 centimeter in diameter. The Keloid nodule remains round with a glossy surface and as it grows, it maintains its round appearance unless it transforms into a keloid tumor, or massive keloid, when it loses its round appearance. Nodular Keloids are commonly seen in Africans/ African Americans or individual with black skin color.

“Keloid Tumors” refer to any keloid nodule that grows to a diameter of greater than two centimeters.

“Linear Keloid” appear like a line that can run in any direction on the skin, and over time can expand in size.

“Flat Keloid - Keloidal Plaque:” refer to the type of lesion that tend to spread sideways, as opposed to raising from the skin surface. Flat keloids grow and spread on the surface of the skin and hardly form a nodule. This is the most common form of keloid seen in Caucasians and individuals with light and fair skin color.

“Butterfly Keloid” refer to the keloids that their appearance is similar to butterfly. These keloid grow from their sides and as they grow sideways, their wings spread wider. Butterfly keloids often form in central chest area, over sternum [sternum].

“Guttate Keloid” refers to a unique pattern of presentation of Keloid disorder whereby the affected individual has numerous round and small keloid spots, which are often clustered in one area of the skin. This pattern of keloid lesions mimics the pattern of guttate psoriasis, with the difference being the lesions are keloidal in nature.

“Hyper-inflammatory Keloids” refer to keloids that are extremely painful and tender to touch. This type of keloid is oftentimes seen in central chest area, and takes a butterfly shape. Pain and discomfort of this type of keloid is often very hard to manage.

“Superficially Spreading Keloids” are those keloids that have a rather rapid rate of growth and spread and involve very large areas of the skin. Often adjacent keloids merge and form of a much larger keloid.

“Pedunculated Keloid” is a keloid lesion that grows like a mushroom, with a stalk connecting the bulk of keloid to the underlying skin. This type of keloid is often seen in earlobes.

“Bulky Keloids” are either a conglomerate of several keloid nodules that have merged with each other, or are due to an overgrowth of a single nodule that continues to increase in size. Bulky keloids measure between 5-10 centimeters in diameter and almost always interfere with daily life of the affected person. These keloids are often noticeable under thin clothing. They can be irritated, or pulled during sleep when the person tosses and turn in bed, waking the person up with pain from pulling of the keloid lesions. Bulky keloids can develop in any part of the skin, including on the face. Surgical removal of small keloids often results in formation of bulky keloids.

”Massive Keloids” are those that are quite bulky, measuring over 10 centimeters in diameter, and by their nature see no boundaries and will spread in all directions never stop growing. Continuous growth of a keloid, which is oftentimes worsened by surgical removal of an existing keloid, leads to formation of massive. Massive keloids are almost unique to Africans, African Americans and individuals with black skin color and always interfere with person’s daily life, and even range of motion of the joints in the involved area.

Topographical

Keloid lesions can form in unique and well defined parts of the skin; and in each part, the keloid lesions can display a unique shape and form.

“Scalp Keloids” often form in the occipital area and are common among individuals with black color skin.

“Ear Keloids” form on the ears, almost always at the site of a prior piercing of the ear.

“Earlobe keloids” appear as a ball of tissue growing on one or both sides of the earlobes.

“Posterior Auricular Keloids” are those that form behind the ears, and often develop following surgery in this area.

“Facial Keloids” appear as either flat lines or nodules on the face. This condition is common among as well as Asians.

“Neck Keloids” appear often as a liner or nodular keloids. Over time these keloids grow to larger sizes. Neck keloids are more commonly seen among Africans/African Americans and those with black color skin.

“Chest Wall Keloids” consist of keloids that occur on the chest, often over sternum. Upper chest wall, including the shoulder areas, is the most prevalent location for keloid formation.

“Upper Arm Keloids” consist of keloids that form on upper arm / shoulders areas. BCG Vaccination is one of the triggering factors of forming upper arm keloids.

“Umbilical Keloids” consist of keloids that form around umbilicus. These keloids are often triggered by piecing of the skin in this area, or after laparascopic surgery incisions that are made in this area.

“Pubic Keloids” develop in pubic area, most commonly seen among Africans/African Americans and those with black color skin whereby the disease can results in formation of bulky, or massive keloids. Pubic keloids is also seen among Asians, but it is almost always a flat and small lesions.

In addition to these unique locations, keloids can practically form on any part of our skin. The author, htirgan has treated over 800 keloid patients and has (a) observed only one case of keloid formation on the forehead in an African American who had minor surgery to remove a cyst from his forehead, who later on developed a keloid at the site of surgery; and (b) none on eyelids and palms of the hands.

Keloids can rarely form in the sole of feet. This only happens in patients who suffer from massive keloids.

Treatment

Surgical removal of keloids is an area of great controversy. The biggest risk associated with surgical keloid removal is the risk of recurrence after surgery. Keloids that recur after surgery are often bigger and much harder to treat. The onset of a keloid is triggered by a minor wound in the skin, such as piercing the ears. In surgically removing a keloid, a much larger wound is induced by the surgeon. This new and larger wound will obviously result in formation a much larger keloid.

Predicting the risk of recurrence of a keloid after surgical removal is impossible. What is greatly needed is a methodology to make a risk determination as to which keloids will recur and which will not. This is an area that needs to be properly researched.

The risk of recurrence after surgery for certain keloids such as chest wall, shoulder keloids is near 100%. Local injection of steroids after surgery reduces the risk of recurrence of certain keloids in the earlobe, not in other parts of the body. The degree of benefit from this intervention is unclear.

Radiation therapy is also utilized to reduce the risk of recurrence. Although it can reduce the risk of recurrence to some extent, Radiation carries a major risk of causing cancers and should not be used to treat keloids in young and healthy individuals.

Surgery

Treatment of keloid disorder is challenged by the fact that no matter how the keloid lesion is treated, one cannot alter the genetic makeup of the person’s skin, and since the genetic abnormality stays with the person, any form of newly induced injury to the skin, i.e. Surgery, often results in formation of a new, yet bigger keloid at the site of original keloid. This general rule applies to all keloids, perhaps with one exception, and that is pedunculated, mushroom type keloids that grow on the ear in patients who have no family history of keloid and have no other keloids on their body, and yet no surgeon can, or will guarantee that the keloid will not regrow after surgery.

It is well understood that keloid is a genetic and an inherited disorder of the wound healing mechanisms of the skin. Surgery cannot change the genetic makeup of the person. Surgery only triggers the abnormal wound healing response, which is the core problem in keloid formation, and commonly results in development of a much more complex and bigger keloid.

Certain people with keloid however, may benefit from surgery. To this date we do not have a method of predicting who will benefit from surgery and who will not. Pedunculated Earlobe Keloids (those with a stalk) in patients who are at lowest risk of recurrence, i.e. those with no other keloids on their skin, and those with negative family history of keloid, can be considered for surgery. There are reports from Korea of successful multimodality treatments of earlobe keloids, using surgery, steroid injections, magnetic pressure earrings, etc. These results are very encouraging, yet they need to be re-produced in individuals who are from African ancestry.

Steroid injection

With well established, nearly 100% recurrence rate of keloids after surgery, efforts have been made to mitigate the risk of recurrence. Most commonly practiced approach is to inject the site of surgery with steroids. This approach has never been standardized, and every practitioner has his/her way of injecting the surgical site.

People who are considering surgery should have a one-on-one discussion with their surgeon, exploring the odds of recurrence of keloid after surgery. Lack of proper patient education by the surgeons often results in unnecessary surgery on keloid patients who have 100% chance of recurrence after surgery.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy is a method of treating cancers. Radiation therapy uses high-energy particles or waves, such as x-rays, gamma rays, electron beams, or protons, to destroy or damage cancer cells. Same radiation is used for treatment of keloids often after the keloid is removed surgically. Radiation therapy remains a rather controversial issue in treatment of keloid with the most important concern being the development of cancer and other serious medical complications following this method of treatment.

Cancer risk

Women will have a much higher risk of breast cancer if they receive radiation in their chest. In the past two decades, there has been strong opposition to performing routine mammograms in women, for fear of mammogram causing breast cancer. The dose of radiation used in mammography is about 0.3 cGy. After 20 annual mammograms, a woman will receive only 6 cGy or radiation. The dose used in treating keloids varies form 1,000-1,800 cGy. Despite the knowledge about the carcinogenic risk of radiation, some radiation therapy centers still deliver this treatment to young keloid patients. We also know that exposure to radiation in Hiroshima and Chernobyl resulted in excess risk of various cancers and leukemia.

Radiation Therapy should not be used for treatment of keloids. Several decades ago, radiation therapy at even lower doses was used for treatment of acne and fungal infections of the scalp. Although very effective, these practices were banned because of documented increased risk of cancer among the treated patients. Perhaps economy plays a role in utilization of radiation therapy in keloid patients. Cost of delivery of radiation therapy to a keloid is in excess of $10,000.

Radiation therapy not only can cause cancer, but also causes permanent damage to the tissue that are in the vicinity of treated area. Radiation can damage the organs that are under the area where keloid is located. Radiating neck will result in total loss of thyroid function, making the person hypothyroid, requiring lifelong thyroid supplement medications. Radiation to the chest area can damage the heart and lungs. Radiating abdomen can damage the liver. Radiation the pelvis can damage the bone marrow, ovaries in women and testicles in men, potentially causing infertility.

Effectiveness

Despite all these risks, there is no guarantee that the addition of radiation can prevent recurrence of keloid, a risk that often is not discussed with the patients undergoing radiation therapy for keloid.

Cryotherapy

Cryotherapy, also known as Cryosurgery is the application of extreme cold to treat, or destroy keloids. Cryotherapy is used to treat a number of skin conditions like warts, moles, skin tags, skin cancer, tattoos, etc., as well as keloids and hypertrophic scars. Cryotherapy utilizes Liquid Nitrogen that is capable of producing extreme low temperatures. About 80% of the air we breathe is made of nitrogen. Nitrogen is an inert gas and does not react with anything. It is not flammable either. Under extreme pressure, air and specially nitrogen, transforms shape and becomes liquid. Upon evaporation, liquid nitrogen produces extreme cold, -196 Celsius.

Application of liquid nitrogen to keloid tissue results in freeze destruction of keloid tissue. Exposure to extremely cold temperatures for an extended period of time causes frostbites which can lead to loss of finger and toes in mountain climbers who are not well prepared. We utilize the same principal in treating keloids, and induce very precise frostbite in the keloid tissue by direct application of liquid nitrogen to the keloid.

Unfortunately, this effective method of treatment is underutilized, and often when used, it is not used properly. Cryotherapy, is the safest, least expensive and free of long term side effects.

Epidemiology

Like all other aspects of Keloid Disorder, epidemiology of this disorder, its true incidence and prevalence has never been properly studied. True incidence and prevalence of keloid in United States is not known. Indeed, there has never been a population study to assess the epidemiology of this disorder. In his 2001 publication, Marneros[6] stated that “reported incidence of keloids in the general population ranges from a high of 16% among the adults in Zaire to a low of 0.09% in England,” quoting from Bloom’s 1956 publication on heredity of keloids.[7] We do however know, from clinical observations that the disorder is more common among Africans, African Americans and Asians with unreliable and very wide estimated prevalence rates ranging from 4.5-16%.[8][9] Thorough and scientific population and epidemiology studies of this disorder are desperately needed.

Center for Disease Control [CDC] does not follow this disorder, therefore we have no reliable indication as to its incidence or prevalence in United States. World Health Organization [WHO] does not follow this disorder either. Keloid Disorder is quite common in sub-Saharan Africa.

A recent epidemiology report from Tunisia on 28,244 dermatology clinic visits was published[10] without mentioning Keloid even once in the publication. It is hard to believe that there is a country on earth, let alone in North Africa, where keloid does not exist as a disease entity.

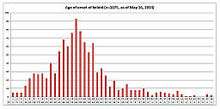

Age of onset

Age of onset of keloid disorder has never been systematically studied. Our current understanding of the age of onset and age distribution of keloid disorder is solely based on observation or citations of very old literature, or studies that have had aims other than studying the true age of onset of keloid disorder. While studying genetics of keloid disorder, Clark et al. studied 5 families with total of 35 affected individuals with various phenotypes and distribution of keloidal lesions.

Age of onset of keloid disorder was obtained by taking history from the study subjects. The age reported for first keloid development varied from 5 to 52 years, although most subjects examined (50%) reported onset of their first keloid between 10 and 19 years. Similarly when individuals with multiple keloids were asked to recall onset age of each lesion, participants reported the largest number of keloids (46%) appearing between 10 and 19 years.

An IRB approved online survey was launched in November 2011 by this author to capture various detailed information directly from KD patients[11] including the age at which the study participants would recall to have developed their very first keloidal lesion. As of May 16, 2014, 1,391 patients with keloid disorder had participated in this survey, among which 1,075 participants provided the age when they developed their first keloid. Parents and guardians comprised a very small proportion of respondents (<4%) answering the survey on behalf of their underage children. Individuals from various countries with access to internet participated in this survey.

Author, Michael Tirgan has personally treated and published the case of a 5 years old female who developed her first keloid at age of 9 months,[12] youngest age of developing keloid ever reported in the medical literature.

Analysis of this data revealed that the age of onset of keloid disorder for great majority (approximately 82%) of patients is between 5 and 25, with 54.6% of patients being diagnosed before age of 18; establishing keloid disorder as one of the most common chronic cutaneous childhood disorders. Additionally, subset analysis of our data revealed a strong correlation between the age of onset and pattern of distribution of keloid disorder with shoulder, upper arm, and ear and earlobe keloids to present at a much younger age as opposed to keloids in other regions.

References

[12]; -webkit-column-width: [6]

[12]; list-style-type: decimal;">

- ↑ MedlinePlus Encyclopedia Keloids

- ↑ Li, K; Barankin, B (February 2013). "Dermacase. Can you identify this condition? Acne keloidalis nuchae.". Canadian Family Physician. 59 (2): 159–60. PMID 23418243.

- 1 2 3 4 Ramakrishnan, K. M.; Thomas, K. P.; Sundararajan, C. R. (1974). "Study of 1,000 patients with keloids in South India". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 53 (3): 276–80. doi:10.1097/00006534-197403000-00004. PMID 4813760.

- 1 2 3 4 Lane, J. E.; Waller, J. L.; Davis, L. S. (2005). "Relationship Between Age of Ear Piercing and Keloid Formation". Pediatrics. 115 (5): 1312–4. doi:10.1542/peds.2004-1085. PMID 15867040.

- 1 2 3 4 Pierce, H. E. (1979). "Keloids: Enigma of the plastic surgeon". Journal of the National Medical Association. 71 (12): 1177–80. PMC 2537457

. PMID 522181.

. PMID 522181. - 1 2 3 Marneros, Alexander G.; Norris, James E. C.; Olsen, Bjorn R.; Reichenberger, Ernst (2001). "Clinical Genetics of Familial Keloids". Archives of Dermatology. 137 (11): 1429–34. doi:10.1001/archderm.137.11.1429. PMID 11708945.

- 1 2 3 4 Bloom, D (1956). "Heredity of keloids; review of the literature and report of a family with multiple keloids in five generations". New York state journal of medicine. 56 (4): 511–9. PMID 13288798.

- 1 2 3 4 Froelich, K.; Staudenmaier, R.; Kleinsasser, N.; Hagen, R. (2007). "Therapy of auricular keloids: Review of different treatment modalities and proposal for a therapeutic algorithm". European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology. 264 (12): 1497–508. doi:10.1007/s00405-007-0383-0. PMID 17628822.

- 1 2 3 4 Gauglitz, Gerd; Korting, Hans; Pavicic, T; Ruzicka, T; Jeschke, M. G. (2011). "Hypertrophic scarring and keloids: Pathomechanisms and current and emerging treatment strategies". Molecular Medicine. 17 (1–2): 113–25. doi:10.2119/molmed.2009.00153. PMC 3022978

. PMID 20927486.

. PMID 20927486. - 1 2 3 4 Souissi, A; Zeglaoui, F; Zouari, B; Kamoun, M. R. (2007). "A study of skin diseases in Tunis. An analysis of 28,244 dermatological outpatient cases" (PDF). Acta Dermatovenerologica Alpina, Pannonica et Adriatica. 16 (3): 111–6. PMID 17994171.

- 1 2 3 4 Clinical trial number NCT01423981 for "Web Based Investigation of Natural History of Keloid; An Online Survey of Patients With Keloid" at ClinicalTrials.gov

- 1 2 3 4 Tirgan, M. H.; Shutty, C. M.; Park, T. H. (2012). "Nine-Month-Old Patient with Bilateral Earlobe Keloids". Pediatrics. 131 (1): e313–7. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-0075. PMID 23248221.