Keynsham

| Keynsham | |

Keynsham High Street |

|

Keynsham |

|

| Population | 16,641 (2011)[1] |

|---|---|

| OS grid reference | ST654684 |

| Civil parish | Keynsham |

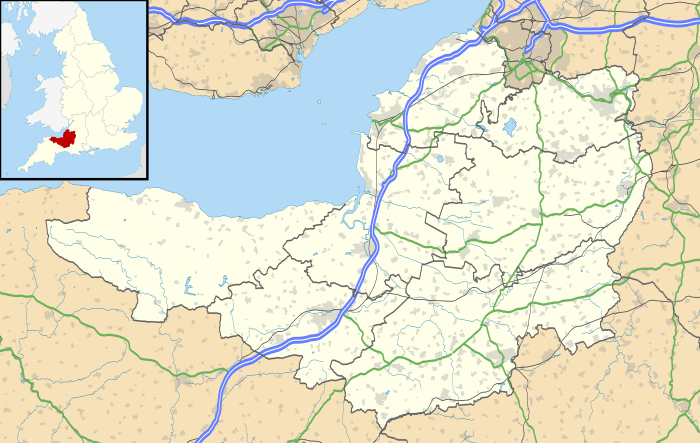

| Unitary authority | Bath and North East Somerset |

| Ceremonial county | Somerset |

| Region | South West |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | BRISTOL |

| Postcode district | BS31 2 |

| Dialling code | 0117 |

| Police | Avon and Somerset |

| Fire | Avon |

| Ambulance | South Western |

| EU Parliament | South West England |

| UK Parliament | North East Somerset |

Coordinates: 51°24′49″N 2°29′48″W / 51.4135°N 2.4968°W

Keynsham /ˈkeɪnʃəm/ is a town and civil parish between Bristol and Bath in Somerset, south-west England. It has a population of 16,000.[1] It was listed in the Domesday Book as Cainesham, which is believed to mean the home of Saint Keyne.

The site of the town has been occupied since prehistoric times, and may have been the site of the Roman settlement of Trajectus. The remains of at least two Roman villas have been excavated, and an additional 15 Roman buildings have been detected beneath the Keynsham Hams. Keynsham developed into a medieval market town after Keynsham Abbey was founded around 1170. It is situated at the confluence of the River Chew and River Avon and was subject to serious flooding before the creation of Chew Valley Lake and river level controls at Keynsham Lock in 1727. The Great Flood of 1968 inundated large parts of the town. It was home to the Cadbury's chocolate factory, Somerdale, which opened in 1935 as a major employer in the town.

It is home to Memorial Park, which is used for the annual town festival and several nature reserves. The town is served by Keynsham railway station on the London-Bristol and Bristol-Southampton trunk routes and is close to the A4 road which bypassed the town in 1964. There are schools, religious, sporting, and cultural clubs and venues.

History

Roman Trajectus

Evidence of occupation dates back to prehistoric times, and during the Roman period, Keynsham may have been the site of the Roman settlement of Trajectus, which is the Latin word for "bridgehead."[2] It is believed that a settlement around a Roman ford over the River Avon existed somewhere in the vicinity, and the numerous Roman ruins discovered in Keynsham make it a likely candidate for this lost settlement.

In 1877 during construction of the Durley Hill Cemetery, the remains of a grand Roman villa with over 30 rooms was discovered.[3][4] Unfortunately, construction of the cemetery went ahead, and the majority of the villa is now located beneath the Victorian cemetery and an adjacent road. The cemetery was expanded in 1922, and an archeological dig was carried out ahead of the interments, leading to the excavation of 17 rooms and the rescue of 10 elaborate mosaics.[3]

At the same time as the grand Roman villa was being excavated at Durley Hill Cemetery, a second, much smaller Roman villas was discovered during the construction of Fry's Somerdale Chocolate Factory.[3] Two fine stone coffins were also excavated, interred with the remains of a male and a female. The villa and coffins were removed from the site, and reconstructed near the gates of the factory grounds, and construction on the factory went ahead. Fry's constructed a museum on the grounds of the factory, which house the Durley Hill mosaics, the coffins, and numerous other artifacts for many years.[4] The factory was shuttered in 2011, and the property sold to Taylor Wimpey for redevelopment into a housing community. In 2012, Taylor Wimpey carried out a detailed geophysical assessment of the area, and discovered an additional 15 Roman buildings centered around a Roman road beneath Keynsham Hams, with evidence of additional Roman buildings that have been disturbed by quarrying.[2][4] Currently, there are no plans to excavate the Roman ruins at Keynsham Hams.

Medieval Keynsham

According to legend, Saint Keyne, daughter of King Brychan of Brycheiniog (Brecon),[5] lived here on the banks of the River Avon during the 5th century. Before settling here, she had been warned by the local King that the marshy area was swarming with snakes, which prevented habitation. St Keyne prayed to the heavens and turned the snakes to stone.[6] The fossil ammonites found in the area were believed to be the result.[7] However, there is no evidence that her cult was ever celebrated in Keynsham.

Some scattered archeological evidence suggests that an Anglo-Saxon settlement existed in Keynsham in the High Street area, and that in the 9th century a Minster church existed in Keynsham as well.[8] The earliest documentary reference to Keynsham is in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, (c. 980) which refers to it as Cægineshamme, Old English for 'Cæga's Hamm.'[8] The town is also listed in the Domesday Book of 1086 as "Cainesham." It has therefore been suggested that the origin of Keynsham's name is not, in fact Saint Keyne, but from "Ceagin (Caega)."[9]

Around 1170, Keynsham Abbey was founded by the Victorine congregation of canon regulars. Archeological evidence suggests that the abbey was built over the site of the previous Saxon Minster church.[8] The settlement developed into a medieval market town, and the abbey of Keynsham was given ownership of the Keynsham Hundred.[10] The Abbey survived until the dissolution of the monasteries in 1539, and a house was subsequently built on the site. The remains have been designated as a Grade I listed building by English Heritage.[11]

Modern history

Keynsham played a part in the Civil War as the Roundheads saved the town and also camped there for the night, using the pub now known as the Lock Keeper Inn as a guard post.[12] During the Monmouth Rebellion of 1685 the town was the site of a battle between royalist forces and the rebel Duke of Monmouth.[12] Bridges Almshouses were built around 1685 and may have been for the widows of those killed in the rebellion.[13]

Post World War II

Before the creation of Chew Valley Lake and river level controls at Keynsham Lock and weir, Keynsham was prone to flooding. The Great Flood of 1968 inundated large parts of the town, destroying the town's bridges including the county bridge over the Avon which had stood since medieval times, and private premises on Dapps Hill; the devastation was viewed by the Duke of Edinburgh.[14] After the flood the Memorial Park, which had been laid out after World War II was extended.[15]

Keynsham rose to fame during the late 1950s and early 1960s when it featured in a long-running series of advertisements on Radio Luxembourg for Horace Batchelor's Infra-draw betting system.[16] To obtain the system, listeners had to write to Batchelor's Keynsham post office box, and Keynsham was always painstakingly spelled out on-air, with Batchelor famously intoning "Keynsham – spelt K-E-Y-N-S-H-A-M – Keynsham, Bristol". This was done because the proper pronunciation of Keynsham – "Cane-sham" – does not make the spelling of Keynsham immediately obvious to the radio listener.[17]

Since the 1950s Keynsham has become a dormitory town for Bristol and Bath. The High Street shopping area has been remodelled, and a Town Hall, Library, and Clock Tower were built in the mid-1960s.[18][19]

2010s regeneration

Design work for regeneration of the town hall area was awarded by Bath and North East Somerset Council to Aedas in 2010,[20] with the works cost stated in 2011 to be £33 million[21] (£34 million in 2012).[22] Realisation of the plans is hoped to "attract new business and jobs", in the aftermath of the announcement of the Cadbury Somerdale Factory closure.[20]

In January 2012, it was announced that the Willmott Dixon Group had been appointed as contractor on the scheme.[23][24] The Council's planning committee in August 2012 deferred the approval decision, pending alterations to the external appearance of the building.[25][26] These were approved in October 2012,[27][28] with demolition commencing in the same month.[29][30][31] The regenerated Civic Centre area came back into use in late 2014 and early 2015.[32]

Governance

The town council has responsibility for local issues, including setting an annual precept (local rate) to cover the council’s operating costs and producing annual accounts for public scrutiny. The town council evaluates local planning applications and works with the local police, district council officers, and neighbourhood watch groups on matters of crime, security, and traffic. The town council's role includes projects for the maintenance and repair of parish facilities, such as the village hall or community centre, as well as consulting with the district council on the maintenance, repair, and improvement of highways, drainage, footpaths, public transport, and street cleaning.

Playing fields and playgrounds are provided in Memorial Park, Downfield, Kelston Road, Teviot Road, Holmoak Road and Manor Road with basketball facilities at Teviot Road and Holmoak Road and a BMX track at Keynsham Road. The Keynsham town council is also responsible for the football pitches and pavilion at Manor Road and the floodlit Multi Sport Site in Memorial Park. It also provides support for community groups organising music and cultural events.[33] Conservation matters (including trees and listed buildings) and environmental issues are also of interest to the council. The town council was formed in 1991 and consists of 15 members elected every four years.[34] There are 2 Labour and 13 Conservative.[35] Keynsham has one official twin town: Libourne in France.[36]

From 1974 to 1996, Keynsham was administered as part of the short-lived county of Avon; it has since formed part of the unitary authority of Bath and North East Somerset, in the ceremonial county of Somerset. Bath and North East Somerset which was created in 1996, was established by the Local Government Act 1992. The town is divided into Keynhsam North, which has five Conservative councillors, Keynsham South which is represented by three Conservative and two Labour councillors, and Keynsham East, which has the remaining 5 councillors, all of whom are Conservatives.[37]

Bath and North East Somerset provides a single tier of local government with responsibility for almost all local government functions within its area including local planning and building control, local roads, council housing, environmental health, markets and fairs, refuse collection, recycling, cemeteries, crematoria, leisure services, parks, and tourism. It is also responsible for education, social services, libraries, main roads, public transport, trading standards, waste disposal and strategic planning, although fire, police and ambulance services are provided jointly with other authorities through the Avon Fire and Rescue Service, Avon and Somerset Constabulary and the Great Western Ambulance Service.

Bath and North East Somerset's area covers part of the ceremonial county of Somerset but it is administered independently of the non-metropolitan county. Its administrative headquarters is in Bath, but many departments are headquartered in Keynsham. Between 1 April 1974 and 1 April 1996, it was the Wansdyke district and the City of Bath of the county of Avon.[38] Before 1974 that the parish was part of the Keynsham Urban District.[39]

The parish is represented in the House of Commons of the Parliament of the United Kingdom as part of the North East Somerset constituency, which is a county constituency created by the Boundary Commission for England as the successor seat to the Wansdyke Parliamentary Seat. It came into being at the 2010 general election, and is represented by the Conservative Jacob Rees-Mogg. It elects one Member of Parliament (MP) by the first past the post system of election. It is also part of the South West England constituency of the European Parliament which elects six MEPs using the d'Hondt method of party-list proportional representation.

Geography

Keynsham is located where the River Chew meets the River Avon. Fishing rights for the Millground and Chewton sections of the Chew are owned by Keynsham Angling Club. The Mill Ground stretch of the River Chew consists of the six fields on the western bank from Chewton Place at Chewton Keynsham to the Albert Mill. The water is home to Chub, Roach, European perch and Rudd, along with good numbers of Gudgeon, Dace and Trout.[40] Keynsham Lock on the Avon opened in 1727.[41] Just above the lock are some visitor moorings and a pub, on an island between the lock and the weir. The weir side of the island is also the mouth of the River Chew.

Memorial Park, the northern part of which has existed as parkland since the 19th century,[42] as shown by the ordnance Survey maps of 1864 and 1867,[43] was formally laid out after World War II was extended after the floods of 1968.[15] It covers 10.7 hectares (26 acres) of woodland and grass alongside the River Chew. It commemorates the war dead of Keynsham and includes facilities including two children's play areas, a skateboard park, multi-sport area, bowling green, public toilets, a bandstand and refreshment kiosk. The formal gardens within the park are adjacent to the River Chew with the Dapps Hill Woods at its western end.[42] Part of the park is known locally as Chew Park because of its proximity to the River and another area, close to Keynsham Abbey as Abbey Park.[44] The park received the Green Flag Award in 2008/09, and again for 2009/10.[44]

On the outskirts of Keynsham lies Keynsham Humpy Tumps, one of the most floristically rich acidic grassland sites within the Avon area. The site is on a south-facing slope running alongside the Bristol to Bath railway line. It consists of open patches of grassland and bare rock, interspersed with blocks of scrub. It is the only site in Avon at which Upright Chickweed Moenchia erecta, occurs. Other locally notable plant species found here include Annual Knawel Scleranthus annuus, Sand Spurrey Spergularia rubra, Subterranean Clover Trifolium subterraneus and Prickly Sedge Carex muricata ssp. lamprocarpa.[46] The site does not have any statutory conservation status, and is not managed for its biodiversity interest. Threats to its ecological value include the encroachment of scrub onto the grassland areas, and damage from motorcycle scrambling. Between Keynsham and Saltford, a 15 hectares (37 acres) area of green belt has been planted, with over 19,000 trees,[47] as the Manor Road Community Woodland, which has been designated as a Nature Reserve.[48] Nearby is the Avon Valley Country Park tourist attraction.

Along with the rest of South West England, Keynsham has a temperate climate which is generally wetter and milder than the rest of England. The annual mean temperature is about 10 °C (50 °F) with seasonal and diurnal variations, but due to the modifying effect of the sea, the range is less than in most other parts of the United Kingdom. January is the coldest month with mean minimum temperatures between 1 °C (34 °F) and 2 °C (36 °F). July and August are the warmest months in the region with mean daily maxima around 21 °C (70 °F). In general, December is the dullest month and June the sunniest. The south west of England enjoys a favoured location, particularly in summer, when the Azores High extends its influence north-eastwards towards the UK.[49]

Cloud often forms inland, especially near hills, and reduces exposure to sunshine. The average annual sunshine totals around 1600 hours. Rainfall tends to be associated with Atlantic depressions or with convection. In summer, convection caused by solar surface heating sometimes forms shower clouds and a large proportion of the annual precipitation falls from showers and thunderstorms at this time of year. Average rainfall is around 800–900 mm (31–35 in). About 8–15 days of snowfall is typical. November to March have the highest mean wind speeds, with June to August having the lightest. The predominant wind direction is from the south west.[49]

Demography

In the 2001 census Keynsham had a population of 15,533,[1] in 6,545 households, of which 6,480 described themselves as White.[50] Keynsham East Ward had a population of 5,479,[51] Keynsham North 5,035[52] and Keynsham South 5,019.[53] In each of the wards between 75 and 80% of the population described themselves as Christians, and around 15% said that they had no religion.

In 1881 the population of the civil parish was 2,482. This grew gradually until 1931 when there were 4,521, before there was a steeper rise to 1951 when there were 8,277. Over the next ten years this nearly doubled to 15,152 in 1961.[54]

Economy

An important industry in the town was Cadbury's chocolate factory, the Somerdale Factory. The J. S. Fry & Sons business merged with Cadbury in 1919, and moved their factory in the centre of Bristol to Keynsham in 1935.[55] As Quakers, the factory was built in a 228-acre (0.92 km2) greenfield site with social facilities, including playing fields and recreational sports grounds. Called Somerdale after a national competition in 1923, Keynsham Cadbury was the home of Fry's Chocolate Cream, the Double Decker, Dairy Milk and Mini Eggs, Cadbury's Fudge, Chomp and Crunchie.[56]

On 3 October 2007, Cadbury announced plans to close the Somerdale plant by 2010 with the loss of some 500 jobs. Production will be moved to factories in Birmingham and Poland. In the longer term it is likely the greenfield site will be re-classified and provide Keynsham with additional housing. Labour MP for Wansdyke, Dan Norris, said "news of the factory's closure is a hard and heavy blow, not just to the workforce, but to the Keynsham community as a whole".[57] In late 2007 campaigns to save the Cadbury's factory in Somerdale were in full swing. One local resident started a campaign to urge English Heritage to protect the site, and preserve the history of the factory. The campaign did not succeed and as of February 2009 the site is still scheduled for closure, and likely demolition. Cadbury have suggested that the land be redeveloped as a mixture of housing and commercial interests, giving a figure of approximately 900 jobs being created as a result.[58]

Before their takeover of Cadbury in February 2010, Kraft Foods had pledged to keep the Cadbury factory at Somerdale open if they were successful in their bid for the company.[59] However, within a week of completing their purchase of Cadbury, Kraft CEO Irene Rosenfeld released a statement announcing that Kraft were to close the factory by 2011, as originally planned by Cadbury. The stated reason for this was that it was only after the purchase had been made that Kraft realised how advanced Cadbury's plans were.[60] Industry experts have however questioned this explanation, arguing that Kraft invested so much in researching their bid for Cadbury that they should have been aware of the extent to which plans had been advanced.[61]

Culture

In 1969 the town was featured as the title of the fourth album Keynsham by the Bonzo Dog Band. The title was chosen in honour of Horace Batchelor, who had been referenced in previous Bonzo Dog Band recordings.[16] In the early 1960s, Batchelor became known through his regular advertisements on Radio Luxembourg for his football pools prediction service. When giving his contact address, he would slowly spell out 'Keynsham' letter by letter, and this became an amusing feature for many young listeners.

Keynsham Festival, which started in the late 1990s,[62] takes place in the Memorial Park each July,[63] and attracts around 16,000 people.[64] There is also a Victorian evening held in the town each November.[65] Keynsham and Saltford local history society was formed in 1965 and is concerned with researching and recording the history of the area.[66]

Keynsham was chosen as the outdoor location for a dramatic story-line in the BBC One TV serial EastEnders in September 2012 with filming taking place in a cordoned-off section of the High Street.[67][68]

In Northanger Abbey by Jane Austen, Catherine and her friends ride to ″within view of the town of Keynsham″.[69]

Transport

The town is served by Keynsham railway station on the London-Bristol and Bristol-Southampton trunk routes. It opened in 1840 and was renamed Keynsham and Somerdale in 1925. The factory had its own rail system which was connected to the mainline. The connection to Fry's chocolate factory was taken out of use on the 26–27 July 1980. The station's name reverted to Keynsham on 6 May 1974. The station was rebuilt in 1985 as a joint project between British Rail and Avon County Council.[70]

The A4 road used to run through the town, however much of this traffic is now carried on the bypass, which was constructed in 1964.[71] The bypass runs from Saltford, a village which adjoins Keynsham, to Brislington, Bristol. Keynsham is on the Monarch's Way long distance footpath which approximates the escape route taken by King Charles II in 1651 after being defeated in the Battle of Worcester.[72]

The town is served by no less than 9 bus routes, 5 of which connect Bath with Bristol, 1 which runs from Ashton Way at the back of the shops to Bristol City Centre via Kingswood, another bus service runs from Ashton Way at the back of the shops to Southmead Hospital and one bus service runs to Cribbs Causeway. In numerical order:

- A4 Bath to Bristol Airport

- 17 Keynsham to Southmead Hospital

- 19A Bath to Cribbs Causeway

- 38 Bath to Bristol

- 39 Bath to Bristol

- 178 Radstock to Bristol

- 349 Keynsham to Bristol

Education

State-funded schools are organised within the unitary authority of Bath and North East Somerset. A review of Secondary Education in Bath was started in 2007, primarily to reduce surplus provision and reduce the number of single-sex secondary schools in Bath, and to access capital funds available through the government's Building Schools for the Future programme.[73] There are several primary schools in Keynsham, including St Johns primary school, Castle Primary school, Chandag infants and junior school and new school St Keyna primary school (a merge of Keynsham primary school and 150 yr old Temple Primary school). There are also two secondary schools, Wellsway School and Broadlands School.

Wellsway School is an 11–18, mixed comprehensive school which was established in 1971, by amalgamating Keynsham Grammar School and Wellsway County Secondary School both of which opened on a shared site in the mid-1950s. Most students that attend the school live in Keynsham and Saltford or the nearby villages.[74] As of 2007, approximately 1350 students attend the school, ranging in age of 11–18, with 64% achieving 5 or more A-C grades at GCSE.[75] Wellsway's bid for specialist school status was accepted in September 2007. Meaning that Wellsway School now specialises as a Sports and Science College. This means the School has joined the national network of specialist schools, resulting in every school in Bath and North East Somerset now having a specialism. A joint bid is unusual as there are only six schools in the country with a combined Sports and Science specialism.

Broadlands School, with has specialist Science College and Engineering College status, has 1058 students,[76] between the ages of 11 and 16 years. The school opened in 1935.[77]

Nearby Bath has two universities. The University of Bath was established in 1966.[78] It is known, academically, for the physical sciences, mathematics, architecture, management and technology.[79] Bath Spa University was first granted degree-awarding powers in 1992 as a university college (Bath Spa University College), before being granted university status in August 2005.[80] It has schools in Art and Design, Education, English and Creative Studies, Historical and Cultural Studies, Music and the Performing Arts, and Social Sciences.[80] The city contains one further education college, City of Bath College, and several sixth forms as part of both state, private, and public schools. In England, on average in 2006, 45.8% of pupils gained 5 grades A-C including English and Maths; for Bath and North East Somerset pupils taking GCSE at 16 it is 52.0%.[81] Special needs education is provided by Three Ways School.

Religious sites

Begun in 1292, the Anglican parish church of St John the Baptist gradually evolved until taking its present general form during the reign of Charles II, after the tower collapsed into the building during a storm in 1632.[82] The tower, built over the north-east corner of the nave, now rises in three stages over the Western entrance and is surmounted by a pierced parapet and short croketted pinnacles and is said to have been built from the ruins of the abbey church. The south aisle and south porch date from 1390. The chancel, then the responsibility of the abbey, was rebuilt in 1470 and further restoration was carried out in 1634–1655, following the collapse of the tower. There is a pulpit dating from 1634 and is also a screen of the same age which shuts off the choir vestry. It has been designated as a Grade II* listed building.[82]

A former organ is said to have stood in the church, but "had tones so mellow" that Handel bargained for it, offering a peal of bells in exchange.[83] The offer was accepted. The musician went off with the organ and the bells were delivered. There are eight bells in total, some made by the Bilbie family of Chew Stoke,[84] the smallest bears these lines:[84]

"I value not who doth me see

For Thomas Bilbie casted me;

Althow my sound it is but small

I can be heard amongst you all."

St. John the Baptist church is one of five churches in the Church of England Parish of Keynsham,[85] the others being the village churches of St. Michael's in Burnett and St. Margaret's in Queen Charlton, the "Mission Church" in Chewton Keynsham (formerly the school building), and St. Francis' Church on the Park Estate which in 2013 - 2015 underwent extensive modernisation and offers two halls for use by community groups.

There are also the Victoria and Queens Road Methodist churches,[86] St. Dunstan's Roman Catholic Church[87] and an Elim Church.[88] The churches work together, also with churches in Saltford, under the banner of "Churches Together in Keynsham and Saltford" and often with the strapline "More to Life".[89]

Sport

Keynsham Cricket Club play at the Frank Taylor Memorial Ground, their 1st XI compete in the West of England Premier League Division 2. Marcus Trescothick is the most noticeable player to have played for the club. His family remain members of the club, which incorporates over 100 senior members and 100 junior members.

Keynsham rugby football club play at Crown Field.[90] The club's most notable and tragic event occurred on 24 December 1992, when there was a fatal road accident outside the club's ground. A Ford Fiesta car ploughed into 11 people leaving the annual festive disco. One woman, 21-year-old Sarah Monnelle, died at the scene. A second person, 24-year-old rugby player Richard Barnett, died in hospital two days later from his injuries. Clive Sutton was later found guilty on a double charge of causing death by dangerous driving and sentenced to four years in prison at Bristol Crown Court.[91]

Keynsham Town F.C. were founded in 1895.[92] They have played continuously apart from a break during World War II and moved to their current ground, the Crown Field, in 1945.[93] They first played in the Bristol & District League and progressed through the Bristol Combination, Bristol Premier and Somerset Senior League and won the Somerset Senior Cup in 1951–52 and 1957–58.[92][94] They were elected to the Western League in 1973 but were relegated three years later in 1976.[95] Since then they have been promoted to the Premier Division three times and relegated three times. They won the Somerset Senior Cup for the third time in 2002–03[94] and reached the 5th round of the FA Vase in 2003–04.[96] They currently play in the Western Football League Division 1.[92]

There is a bowls club situated at the Memorial Park. Keynsham leisure centre was built in 1965 by British Gas as a gift to the town. It includes a swimming pool, gymnasium and sauna.[97]

Notable residents

Several notable people have been born or lived in Keynsham. The comedian Bill Bailey was raised in the town.[98] Another entertainer Neil Forrester, who was a research assistant and became known as a cast member on The Real World: London was also a local.[99] Sports players from Keynsham include Mark Regan a professional rugby player and a former player at Keynsham Rugby Football Club,[100][101] Luke Sutton of Lancashire County Cricket Club who played as both a wicket-keeper and batsman,[102] Marcus Trescothick, the Somerset and England cricketer.[103] and Judd Trump, a professional snooker player.[104] Horace Batchelor, the football pools forecaster lived in Keynsham, making the town famous by spelling its name on Radio Luxembourg adverts. Author Christina Hollis was born and raised in Queen's Road.

References

- 1 2 3 "Keynsham Parish". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 31 December 2013.

- 1 2 The Bristol Post (11 Oct 2012). "Roman Ruins Found Under Former Chocolate Factory". The Bristol Post. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- 1 2 3 Johnston, David E. (2002). Discovering Roman Britain (3. ed.). Princes Risborough: Shire Publ. ISBN 0747804524. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- 1 2 3 Wyatt, Richard. "Could Roman Bath Have A Nearby Rival?". thevirtualmuseumofbath.com. The Virtual Museum of Bath. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- ↑ Robinson, Stephen (1992). Somerset Place Names. Wimbourne: The Dovecote Press Ltd. ISBN 1-874336-03-2.

- ↑ "Keynsham". Royal British Legion. Retrieved 6 June 2012.

- ↑ Readers' Digest (1979) [1977]. Folklore, Myth and Legends of Ancient Britain. London: Readers' Digest. p. 158.

- 1 2 3 "Keynsham Conservation Area Appraisal" (PDF). democracy.bathes.gov.uk. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ↑ Farmer, David Hugh (2011). The Oxford Dictionary of Saints (5th ed. Rev. ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 255. ISBN 9780199596607. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- ↑ "Somerset Hundreds". GENUKI. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- ↑ "Keynsham Abbey". Images of England. Retrieved 18 July 2007.

- 1 2 Clark, Pete. "Keynshams part in the Monmouth Rebellion". Keynsham Community Website. Archived from the original on 5 March 2010. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ↑ "Bridges Almshouses". National Heritage List for England. English Heritage. Retrieved 5 June 2014.

- ↑ "The day the rains came". Evening Post. 15 July 2008. Retrieved 13 June 2010.

- 1 2 "Memorial Park, Keynsham, Keynsham, England". Parks & Gardens UK. Parks and Gardens Data Services Limited (PGDS). Retrieved 9 June 2013.

- 1 2 "Doing the Keynsham pools". Bath Chronicle. This is Bath. 11 March 2009. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ↑ "Doing the Keynsham pools". Bath Chronicle. This is Bath. Retrieved 2 February 2009.

- ↑ "Keynsham Regeneration Gallery". Bath and North East Somerset Council. Retrieved 18 January 2015.

- ↑ "Keynsham in focus". BusinessMatters. Bath and North East Somerset Council. Archived from the original on 11 September 2011.

- 1 2 "Council picks Aedas for regeneration". Building Design. 21 December 2010. Archived from the original on 2011-01-11. Retrieved 21 January 2013.

- ↑ "Council shows £33m Keynsham regeneration plans". BBC. 21 February 2011. Retrieved 21 January 2013.

- ↑ "Aedas submits £34m designs for Keynsham town centre". News. Building Design. 10 April 2012. Retrieved 21 January 2013.

- ↑ "Keynsham regeneration: Constructor chosen for £34m scheme". BBC. 16 January 2012. Retrieved 21 January 2013.

- ↑ "Willmott Dixon takes Keynsham regeneration". Builder & Engineer. 26 January 2012. Retrieved 21 January 2013.

- ↑ "Keynsham town centre £34m development plans on hold". BBC. 29 August 2012. Retrieved 21 January 2013.

- ↑ "Deferral For Keynsham Regeneration". NOW Bath. 3 September 2012. Retrieved 21 January 2013.

- ↑ "Keynsham town centre £33m development plans approved". BBC. 24 October 2012. Retrieved 21 January 2013.

- ↑ "Green light for Keynsham regeneration". This is Bristol. 24 October 2012. Retrieved 21 January 2013.

- ↑ "Keynsham regeneration: Demolition work begins". BBC. 10 October 2012. Retrieved 21 January 2013.

- ↑ "Keynsham regeneration: Shops demolition starts". BBC. 14 November 2012. Retrieved 21 January 2013.

- ↑ Morris, Tom (10 January 2013). "Regeneration brings a new skyline for town". This is Bristol. Retrieved 21 January 2013.

- ↑ "Police office opens in the centre of Keynsham". Bath Chronicle. 17 January 2015. Retrieved 18 January 2015.

- ↑ "Facilities". Keynsham Town Council. Retrieved 2 September 2010.

- ↑ "Keynsham Town Council". Keynsham Town Council. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ↑ "Councillors". Keynsham Town Council. Retrieved 2 September 2010.

- ↑ "Keynsham and District Twinning Association". Keynsham and District Twinning Association. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ↑ "Councillors Contact Details". BANES. Retrieved 11 November 2010.

- ↑ "The Avon (Structural Change) Order 1995". HMSO. Retrieved 9 December 2007.

- ↑ "Relationships / unit history of KEYNSHAM". A vision of Britain. University of Portsmouth. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ↑ "River Chew". Keynsham Angling Club. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ↑ Allsop, Niall (1987). The Kennet & Avon Canal. Bath: Millstream Book. ISBN 0-948975-15-6.

- 1 2 "Keynsham Memorial Park". Green Flag. Retrieved 2 September 2010.

- ↑ "Keynsham Park". Keynsham Park. Retrieved 2 September 2010.

- 1 2 "Keynsham Memorial Park". BANES. Retrieved 2 September 2010.

- ↑ Historic England. "Albert Mill (Grade II) (1384631)". National Heritage List for England.

- ↑ Green, Ian P.; Higgins, Rupert J.; Kitchen, Mark A.R.; Kitchen, C. (2000). Sarah Myles, ed. The Flora of the Bristol Region. Pisces Publications. pp. 81–83. ISBN 978-1-874357-18-6.

- ↑ "Manor Road Community Woodland, Local Nature Reserve, Keynsham". Avon local nature reserves. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ↑ "Manor Road Community Woodland". Forest of Avon. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- 1 2 "South West England: climate". Met Office. Retrieved 14 March 2010.

- ↑ "Parish Profile – Households". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ↑ "Keynsham East (Ward)". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ↑ "Keynsham North (Ward)". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ↑ "Keynsham South (Ward)". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ↑ "Keynsham CP: Historical statistics: Population". Vision of Britain. University of Portsmouth. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ↑ "Cadbury factories shed 700 jobs". BBC. 3 October 2007. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ↑ "Cadbury's Bristol plant to close by 2011". BBC. 9 February 2010. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ↑ "Cadbury factories shed 700 jobs". BBC News. 3 October 2007. Retrieved 3 October 2007.

- ↑ "900 jobs could be created by Cadbury development". Bath Chronicle. This is Bath. 27 February 2009. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ↑ [http://phx.corporate-ir.net/External.File?item=UGFyZW50SUQ9MTQ1ODZ8Q2 hpbGRJRD0tMXxUeXBlPTM=&t=1 "Takeover bid"]. Thompson Reuters. 7 September 2009. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ↑ "Cadbury's Bristol plant to close by 2011". BBC News. 9 February 2010. Retrieved 19 April 2010.

- ↑ "Cadbury factory closure by Kraft 'despicable'". BBC. 10 February 2010. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ↑ "Keynsham Music Festival". Visit Bath. Retrieved 2 September 2010.

- ↑ "Keynsham Festival". Keynsham Festival. Retrieved 2 September 2010.

- ↑ "Delighted fans say town's music festival hits all the right notes". This is Bath. Retrieved 6 June 2012.

- ↑ "Keynsham Victorian Evening 2009". Keynsham Town Council. Retrieved 2 September 2010.

- ↑ "Keynsham & Saltford local history society". Keynsham & Saltford local history society. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ↑ "Keynsham's spectacular EastEnders stunt explodes onto the screen". Bath and Noryth East Somerset Council. Retrieved 8 December 2012.

- ↑ "Eastenders film crews leave Keynsham". This is Bristol. Retrieved 8 December 2012.

- ↑ "Northanger Abbey - The Republic of Pemberley". Retrieved 7 September 2015.

- ↑ "Keynsham Railway Station". British Railway Stations. Retrieved 6 August 2010.

- ↑ "Photographic archive of Keynsham". The Changing Face of Bristol. Retrieved 6 June 2012.

- ↑ "The Monarch's Way". The Quinton Oracle. 2005. Retrieved 30 August 2008.

- ↑ "Secondary School Reviews". Bath and North East Somerset Council. Archived from the original on 11 June 2008. Retrieved 23 June 2008.

- ↑ "Wellsway School Inspection 2003" (PDF). OFSTED. Retrieved 24 July 2007.

- ↑ "Wellsway School achievement tables". Department for children schools and families. Retrieved 24 July 2007.

- ↑ "Broadlands School". Ofsted. Retrieved 31 March 2009.

- ↑ "History". Broadlands School. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ↑ "History of the University". University of Bath. Archived from the original on 12 November 2007. Retrieved 10 December 2007.

- ↑ "Departments". University of Bath. Retrieved 10 December 2007.

- 1 2 "Bath Spa University". Bath Spa University. Retrieved 10 December 2007.

- ↑ "LDF Contextual Info" (Excel). Intelligence West. Retrieved 14 December 2007.

- 1 2 "Church of St John the Baptist". Images of England. English Heritage. Retrieved 24 March 2009.

- ↑ Johnstone, H. Diack. "Claver Morris, an Early Eighteenth-Century English Physician and Amateur Musician Extraordinaire". Journal of the Royal Musical Association. 133 (1).

- 1 2 Moore, J. Rice, R. and Hucker, E. (1995). Bilbie and the Chew Valley clockmakers : the story of the renowned family of Somerset bellfounder-clockmakers /Clockmakers. The authors. ISBN 0-9526702-0-8.

- ↑ "Keynsham Parish". Keynsham Parish. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- ↑ "Keynsham Methodist Church". Keynsham Methodist Church. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ↑ "St Dunstan's Catholic Church". St Dunstan's Catholic Church. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- ↑ "Keynsham Elim Church". Keynsham Elim Church. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- ↑ "Churches Together". St Dunstan's Catholic Church. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- ↑ "Location". Keynsham Rugby Club. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ↑ "Stranded tourist's guilt over crash". World: Asia-Pacific. BBC. 15 January 1999. Retrieved 6 August 2010.

- 1 2 3 Williams, M. & T. (2007). Non-League Club Directory 2008. Williams. p. 808. ISBN 978-1-869833-57-2.

- ↑ "The club". Keynsham Town FC. Archived from the original on 10 July 2010. Retrieved 6 August 2010.

- 1 2 "Senior Challenge Cup Competition Winners" (PDF). Somerset Football Association. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- ↑ "Keynsham Town". Table of Club Histories 1950-1 to 2005–2006 K-LA. UK Soccer – Non League Archive. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- ↑ "Keynsham Town". Football Club History Database. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- ↑ "Keynsham Leisure Centre". Aquaterra. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ↑ "Bill Bailey Profile". BBC. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ↑ "Neil Forrester". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 2 September 2010.

- ↑ "Biog – Mark Regan MBE". Mark Regan Enterprises. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ↑ "Mark Regan". Bristol Rugby. Retrieved 2 September 2010.

- ↑ "Luke Sutton". Cricket Archive. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ↑ Marcus Trescothick biography, Cricinfo. Retrieved on 10 June 2007.

- ↑ "Trump departs Keynsham club". Bath Chronicle. This is Bath. 12 November 2009. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Keynsham. |