Ksar Hellal Congress

| 1934 Neo Destour Congress مؤتمر قصر هلال | |

|---|---|

| |

| Genre | Party Congress |

| Date(s) | March 2, 1934 |

| Location(s) | Ksar Hellal |

| Country | Tunisia |

| Next event | Court Street Congress |

| Participants | 60 Delegates |

| Organized by |

Habib Bourguiba Mahmoud El Materi Tahar Sfar Bahri Guiga M'hamed Bourguiba |

|

Outcome Creation of the Neo Destour party Renewal of the Tunisian national movement Colonial repression of 1934 | |

The Ksar Hellal Congress was the first and founding congress of the Neo Destour party. The 1934 Neo Destour Congress was organized by the secessionist members of the Destour party, in Ksar Hellal, on March 2, 1934. It ended, that very night, with the creation of a new political party.

Upon the weakening of the Destour, that adopted a "shy" policy towards the Residence, the colonial French administration in Tunisia, a new generation of provincial thirties, with a European education and a close relationship with the French socialists, emerged. Mainly compounded of Habib Bourguiba, Mahmoud El Materi, Bahri Guiga, Tahar Sfar and M'hamed Bourguiba, it acquired a huge popularity thanks to its bold articles in newspapers, such as L'Action Tunisienne. However, the differences they had with the elders of the party led them to resign from the executive committee, the party's leadership, following the Tunisian naturalization issue.

The congress was held on March 2, 1934 to discuss the continuity of this youth's activism which ended with the founding of their own new political party, the Neo Destour, starting, thanks to its new methods, the renewel of the Tunisian nationalism and its movement.

Historical context

There were numerous reasons leading to the birth of the Neo Destour: The Great Depression and its impact in Tunisia, in the early 1930s, the reactions denouncing the international eucharistic congress of Carthage, held to celebrate the hundredth anniversary of the French colonization of Algeria, the Tunisian naturalization issue but mainly the policy and behavior adopted by the Destour towards these events. Indeed, the party activism decreased in the midst of the 1920s, precisely on January 29, 1926, when "scoundrel decrees" were enacted by the Residence, the French colonial administration. In result, the first exclusively Tunisian labour union, the General Confederation of Tunisian Workers (GCTW), founded by Mohamed Ali El Hammi, was dissolved. Furthemore, nationalist newspapers such as Ifriqiya, Al-Asr, Al Jadid and Le Libéral were prohibited.[1] The party soon bursted in pieces with the departure of Hassen Guellaty and Mohamed Noomane, who founded the Reformist Destourian Party, but also Farhat Ben Ayed, who created the Independent Destourian Party.[2] In this context, a new generation of nationalists emerged.

Background

Emergence of a new generation of nationalists

In the early 1930s, a new generation of nationalists emerged and joined the Destour party. Deeply marked with the Eucharistic Congress of 1930, considered as a "violation of Islam lands by Christianity" and a revolting shame to the Tunisian people, the new generation feared the celebration of the protectorate's 50th anniversary, the next year.[3] In this context, the Destour leadership gathered in L'hôtel d'Orient. Habib Bourguiba, Mahmoud El Materi, Bahri Guiga and Tahar Sfar took part in the meeting.[4] It was decided to support La Voix du Tunisien, a nationalist daily newspaper managed by Chedly Khairallah. Bourguiba, El Materi, Guiga and Sfar decided to join the drafting committee of the paper and stood out from their elders with their daring to challenge the protectorate. Bourguiba wrote:

A State can not be both subject and sovereign: Any treaty of protectorate, because of its nature, carries its own seed of death [...] Is it a lifeless country, a degenerate people who declines? Reduced to be nothing more than a dust of individuals; that means awaiting for downfall [...] In short, total and inevitable demise. Is it, in contrary, a sain people, vigorous, that international races or a momentary crisis forced them to accept the tutelage of a strong state, the necessarily inferior status imposed upon them, the contact of a more advanced civilization determines in them a salutary reaction [...] a real regeneration occurs in them and through judicious assimilation, they inevitably come to realize in stages their final emancipation. Time will tell if the Tunisian people belong to one or the other category.

- New generation of nationalists

-

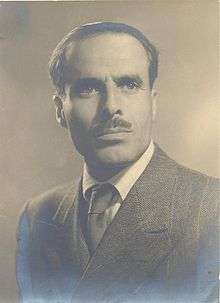

M'hamed Bourguiba

With the originality with which they approached problems, the young team made La Voix du Tunisien a popular newspaper. They soon stood out from their elders of the Destour by establishing a new thinking: They were in favor of the inviolability of the national personality and political sovereignty of the Tunisian people plus a gradual emancipation of the country, by advocating for a nationalism that fought against a regime and not against civilization.[6] But their new thinking soon started a fight with Khairallah about the management of the newspaper. It ended with the resignation of the five editors who decided to found their own paper.[7] A drafting committee gathering Habib and M'hamed Bourguiba, Guiga, Sfar, El Materi and Ali Bouhajeb, a pharmacist friend, created L'Action Tunisienne. Its first edition was published on November 1, 1932. Disappointed in the resigned moderation of their elders, the team worked on defending lower classes and expressing colonial inequalities.[8]

Reviving the national movement: The Tunisian naturalization issue

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Political career

|

||

With the economic crisis that worsened and the popularity of the new generation, the young nationalists felt they needed a good reason to revive the national movement, weakened by the 1926 repression, on new basis. They benefited from the Tunisian naturalization issue that restarted in the early 1930s. Previously, the nationalists protested strongly against the December 20, 1923, laws that favored the access of non-French protectorate inhabitants to French citizenship.[9] The discontent following the enactment of these measures receded but reappeared in the beginning of 1933. On December 31, 1932, upon the announcement of a Muslim naturalized's death in Bizerte, Mohamed Chaabane, individuals gathered in the Muslim cemetery to stop the interment of the dead. They obtained the support of the city's mufti who delivered a fatwa prohibiting naturalized citizens to be buried in Muslim cemeteries.[10]

Bourguiba decided to start a press campaign in L'Action, reprised by many other nationalist newspapers. In order to calm down the turmoil that spread all over the country every time a naturalized died, the Residence asked a fatwa from the Sharaa court, in April. But it resolved nothing: The sheikhs maintained the apostasy of the naturalized but affirmed that if he repented, even verbally, and that before his death, his interment in Muslim lands would be granted.[11] This decision angered nationalists who opposed the fatwa and started riots in Kairouan and Tunis.[12] The campaign led by the new generation of nationalists pressured the Residence to take a two-faced decision: Firstly, it yield to the nationalists stating that naturalized should be buried in special cemeteries. Then, resident-general, François Manceron enacted "scoundrel decrees", granting him the right to imprison at his will any nationalist and suspend newspapers and associations "hostile to the protectorate".[13] Despite that, the victory over the Residence led to the election of El Materi, the Bourguiba brothers, Guiga and Sfar to the executive committee of the party during the extraordinary Destour congress held on May 12 and May 13, 1933.[14]

But the maintained turmoil led the Residence to censor nationalist press and suspend the Destour, on May 31. Bourguiba, deprived of means of expression, benefited from the events of August 8, when riots started in Monastir upon the forced interment of a naturalized's child. The fight between law enforcement and inhabitants ended up with one dead and many injured. Bourguiba then convinced Monastirian notables to choose him as their lawyer in order to defend their case. On September 4, without informing the Destour about his initiative, Bourguiba led a protest delegation to the bey. In response, the party leadership decided to inflict a blame to the young activist, to which Bourguiba responded with his resignation from the party on September 9.[15]

Split-up with the Destour

The rest of L'Action team soon conflicted with the Destour elders. The differences between the groups were not only age but also ideological and methodical. Peyrouton, the new resident-general attempted to calm down the situation by announcing social and economic reforms. By the end of October 1933, he met with a delegation of the Destour executive committee, led by Ahmed Essafi and comprising Salah Farhat, Mohieddine Klibi, Ali Bouhajeb, Moncef Mestiri and Bahri Guiga. He wanted to offer them to join an advisory committee of Tunisian reforms that would stop the transfer, to colonial land agencies, lands mortgaged by farmers reduced to misery. In order to avoid opposition, he asked them to keep these arrangements confidential. At the end of the interview, the delegation members gathered in Moncef Mestiri's house in La Marsa to agree on the portion of the interview to be made public. Guiga, who was a delegation member refused to yiel to "game of the resident" and joined his friends in Tunis to inform them about what had been negotiated. The very evening, he told the manager of Le Petit Matin about the talks with the resident-general.[16]

The news fastly spread in the city which angered Peyrouton and the Destour leadership, mainly Essafi who asked for the gathering of the executive committee on November 17 to force Guiga's exclusion from the party. On December 7, solidary with their friend, M'hamed Bourguiba, El Materi and Tahar Sfar resigned from the executive committee which refused to reconsider its decision.[17] Habib Bourguiba decided to join the "rebel faction", gathered under El Materi's commands, to start an explanation campaign to the activists. Called "traitors" by the Destour, the incident delighted the Residence, as it divided the nationalists.[18]

Preparations

In order to explain themselves to the people, Sfar, Bourguiba and Guiga decided to start a campaign in Ksar Hellal and Moknine, seriously hit by the economic-social crisis. At their arrival, they were subject to the hostility of the inhabitants because of the Destour propaganda to discredit them. However, they found support in Ahmad Ayad, a Ksar Hellal notable, who invited them to hold a gathering and explain themselves. The meeting happened in his house on January 3, 1934. Soon, their speeches and determination to act proved to be successful and pleased the inhabitants. Belgacem Gnaoui, then leader of the carter union and who would become the General secretary of the General Confederation of Tunisian Workers, testified that "at the slightest sign, we were ready to close our shops and march in the streets [...] Young people urged us to protest strikes. On day, Ahmad Essafi, General secretary of the Destour, convened a gathering in the Andalous quarter. He was violently attacked by the participants who accused him of enjoying the comfort while we were starving in our hovels".[19]

Meanwhile, the Destour executive committee pursued its campaign to discredit the new generation of nationalists. In response, Bourguiba replied with more violence, aggression and contempt in his speeches. As for El Materi, they should not stoop to the elders' level; He advocated for reforming the party's methods in peace and understanding or split up from the movement and found their own one. He stated: "My opinion is that we should let them cry in the wilderness, only a few people took them seriously". Sfar also criticized the Destour leadership writing: "Too much conservatism harms society because it is a factor of immobility and death; it solidifies everything, destroyes all initiative spirit, opposes any vivifying and creating force and therefore stops any progress, breaks the momentum and growth of individuals and groups".[18]

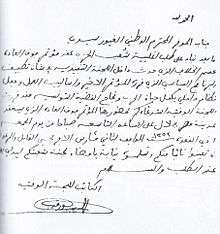

Since then, the number of Destourian representations asking for an extraordinary explanatory congress increased. They addressed letters to Mohieddine Klibi who responded with a revealing stiffening of the danger the young nationalists were for the Destourian establishment. The idea spread across the country mainly in Tunis, Menzel Temime, Moknine, Gafsa and Bizerte. On the other hand, the young team pursued its tour and asked for a loyal showdown with their opponents: An interim committee including El Materi, the Bourguibas, Sfar and Guiga was formed and decided to organize an extraordinary congress on March 2, 1934, in Ksar Hellal to settle the disagreement. They obtained the support of M'hamed Chenik and many of his major clients who guaranteed the smooth progress of the event. Bourguiba drafted the convening letters inviting delegates to participate in order to settle the dispute arose within the Executive committee, develop the propaganda and action methods of the dissenting team. The establishment of a new political movement was even considered.[20]

The congress

Founding of the Neo Destour

On March 2, 1934, 48 members of the Destour attended the event, mostly originating in the Sahel: 19 delegates represented the Sahel in Ksar Hellal while 9 for Tunis and 20 for the rest of the country. Even though invited, neither the members of the executive committee nor that of the cells that remained loyal to it had sent representatives.[20]

During the congress, Sfar denounced the Destour leadership's methods that he judged elitist, accusing them to maintain the people into ignorance. The delegates of the South, such as Metouia and Gafsa, supported these words and confirmed them.[20] Bourguiba then asked the attendees to adjudicate and choose the "men that will have to defend the country liberation on your behalf". For the first time, he stated the Destour leadership of being "ancient" and declared: "We have neither the same conception nor the same views in terms of means of action". The congress proceeded with the proposal of Habib Bougafta, delegate of Bizerte, to declare forfeiture of the executive committee while Belhassine Jrad, delegate of Metouia, required their exclusion from the party.[21]

Once the decisions made, Sfar chaired the adoption of the internal regulation of the new party, making it a strongly hierarchical pyramidal organization, composed by local cells that answer to the Political Office of the party via regional committees and a national Council.[21] The attendees withdrew their endorsement of the executive committee declared "unable to defend the claims of the Tunisian people". Thus, it was replaced within the new party with a Political Office presided by Mahmoud El Materi while Habib Bourguiba was designated General secretary.[22]

A national council (Majlis Milli) was established and composed by 19 delegates, such as Youssef Rouissi and Hédi Chekir.[23] It decided to maintain all the delegates as head of their regions, adopting as a strategy to be in the continuity of the nationalist movement while marginalizing the former leadership.[21]

Neo Destour designated Leadership

| Office | Officeholder |

|---|---|

| President of the party | Mahmoud El Materi |

| General Secretary of the party | Habib Bourguiba |

| Deputy General Secretary of the party | Tahar Sfar |

| Treasurer | M'hamed Bourguiba |

| Deputy Treasurer | Bahri Guiga |

Aftermath

Renewel of the national movement

Once the party founded, its young leaders made it a major asset to express their nationalist claims. In order to do that, the party had to stand out and acquire a major position within the National movement. The economic crisis was favorable to that. Plus, their new thinking shaped the party policy that did not systematically oppose the Residence decisions: In March 1934, Peyrouton adopted deflationary measures to ease the burden of the Tunisian budget and trim much of the French officials' privileges, something that had always been requested by the nationalists. On March 31, Bourguiba decided to publicly endorse this decision, arguing that an initiative responding to nationalist aspirations should be applauded.[24]

But the freshly constituted party still had to impose itself on the political stage, spread its ideology and rally the supporters of a still-powerful Destour. It also had to convince lower classes that the Neo Destour was their defender, inviting them to join and recover a "dignity manhandled by half a century of protectorate". In order to do so, tours were organized throughout the country, which drew a distinction between the new and old parties in their communication field. Despite its significant influence, the Destour did not succeed in mobilizing the illiterate masses whose political weight was still not existing. Cells were created and a structure was formed all around the country, making the Neo Destour a powerful engine more effective than all the preceding nationalist formations.[24] If the elders addressed the colonial power to express their requests, the secessionists addressed the people. To reach these aims, Tahar Sfar created El Amal, an Arabic version of L'Action Tunisienne, which became the party's official paper.

After the "conquest of the people", the political office tried to reach international support. The party sensitized the French left wing to the requests of colonized people. It presented itself as aspiring to acquire a part of the Regence sovereignty, without being anti-French. They gained the support of Félicien Challaye who visited the country with Bourguiba, while on tour. After his return to France, he publicly supported the Neo Destour arguing that he was convinced in the seriousness, the francophilia and the moderation of the young nationalists.[25]

Residence reaction: From delight to repression

A month after the congress, the resident-general, Marcel Peyrouton tried to benefit from the split-up with the Destour, seeing in it a mean to weaken the nationalist movement. Thus, he convened Mahmoud El Materi to whom he proposed a doctor position in Sadiki Hospital and, upon his refusal, proposed to appoint him as the hospital head. El Materi saw in this an attempted corruption and declared to the resident: "Be aware, sir, that I am neither to be bought nor sold".[26] Finding no compromise with the young neo-Destourians, Peyrouton called for the French Rally of Tunisia to show a strong opposition to the new party: "I will cross Tunisia like a hurricane", he declared.[27]

Favorable to the Residence's appeal, the French of Tunisia protested against the national movement. In response, the Neo Destour gathered activists in Place aux Moutons where the nationalist leaders invited the people to resist and march towards the Residence. A delegation comprising Habib and M'hamed Bourguiba, El Materi, Sfar and Ali Dargouth requested to meet the resident-general, who later that day refused. Instead, administration officials demanded that they evacuate the Residence, calmly and without causing incidents.[26] In response, the Neo Destour meetings increased and their contestations too. They demanded national sovereignty and evoked independence "accompanied by a treaty guaranteeing France a preponderance both in the political and economical fields in comparison with other foreign powers", in an article published by L'Action Tunisienne.[28] In order to do so, they required the transfer of government responsibilities, legislative and administrative even if it would preserve French interests in the cultural and economical fields.[29]

These requests started a conflict between the French government and the Tunisian national movement, especially as party officials undertake a major action across the country to raise the people's awareness of their message.[30][31] With the worsening of the economic crisis, Peyrouton wanted to avoid turmoil as the Neo Destour wanted an uprise of the population living in hard conditions. Thus, he responded with a series of measures destined to intimidate the movement.[32] The repression that started was more and more violent: Peyrouton prohibited any nationalist and left wing newspaper, such as Tunis socialiste, L'Humanité and Le Populaire, on September 1, 1934. On September 3, raids were carried out as major party leaderships were arrested, that was both Destours and the communist party.[25] They were placed under house arrest then sent to the military camp of Bordj le Bœuf, in the far South of Tunisia, before being freed two years later with the arrival of Resident-general, Armand Guillon.

Legacy

The date of March 2, 1934, became a major event, both in the History of Tunisia and that of the National movement. After decline of the movement activism, this congress was the return in force of Tunisian nationalism with new ambitions. The new generation, of Sadikian formation then higher education in France, stood out from the Destour elders with Tunis origins and invited the people to masters of their fate.[33] It was also a major date in Bourguiba's political career which permitted him to have a great part in the country liberation then the founding of a modern Republic. The congress also proclaimed the dissolution of the executive committee and endorsed the new party. Thus, two major political parties appeared on the political stage:[34]

- The first, Islamist, conservative, pan-Islamist and traditionalist, conserved the name of Destour and also called the old Destour; [35]

- The second, modernist, secularist, took the name of Neo Destour and established a modern structure based on the model of European socialist and communist parties. It was determined to conquest power and transform the society.[36]

Tunisian scholars described the rivalry between the two parties: "The Old Destour was a party of notables, well-raised distinguished people, Arabists formed in majority in the Ez-Zitouna University. Bourguiba and his fellows had, overall, a very different profile and view. From the petty bourgeoisie of the coast, they were considered, scornfully, as Afaqiyin, those who came from behind the horizon, a euphemism for designating provincials. They had a modern, bilingual education and thus were also comfortable both in French and Arabic, were close to the people, whom they addressed with its spoken language, in Tunisian Arabic, and had the ambition to create a large mass party".[37]

See also

-

History portal

History portal -

Politics portal

Politics portal -

Tunisia portal

Tunisia portal

Footnotes

- ↑ Boularès 2012, p. 546.

- ↑ Boularès 2012, p. 547.

- ↑ Bessis & Belhassen 2012, p. 69.

- ↑ Bessis & Belhassen 2012, p. 70.

- ↑ Martel 1999, p. 24.

- ↑ Bessis & Belhassen 2012, p. 71.

- ↑ Bessis & Belhassen 2012, p. 73.

- ↑ Martel 1999, p. 27.

- ↑ Goldstein, Daniel (1978), Libération ou annexion. Aux chemins croisés de l'histoire tunisienne, 1914–1922, Tunis: Maison tunisienne de l'édition, p. 484

- ↑ Casemajor, Roger (2009), L'action nationaliste en Tunisie, Carthage: MC-Editions, p. 73

- ↑ Bessis & Belhassen 2012, p. 79.

- ↑ Kraïem, Mustapha (1956), Higher Institute of National Movement History, Tunis, p. 75

- ↑ Bessis & Belhassen 2012, p. 80.

- ↑ Mestiri 2011, p. 120.

- ↑ Martel 1999, p. 29.

- ↑ Mestiri 2011, pp. 124–125.

- ↑ Bessis & Belhassen 2012, p. 83.

- 1 2 El Materi Hached 2011, p. 92.

- ↑ Bessis & Belhassen 2012, pp. 84–85.

- 1 2 3 Bessis & Belhassen 2012, p. 86.

- 1 2 3 Bessis & Belhassen 2012, p. 87.

- ↑ El Materi Hached 2011, p. 93.

- ↑ Boularès 2012, p. 568.

- 1 2 Bessis & Belhassen 2012, pp. 90–91.

- 1 2 Martel 1999, p. 32.

- 1 2 El Materi Hached 2011, p. 94.

- ↑ Cohen-Hadria, Elie (1976), Du protectorat français à l'indépendance tunisienne, Nice: Center of Modern and Contemporary Mediterranean, p. 102

- ↑ Histoire du mouvement national tunisien, 9 avril 1938 : le procès Bourguiba, Tunis: National Documentation Centre, 1970, p. 138

- ↑ Le Pautremat & Ageron 2003, p. 109.

- ↑ Le Pautremat & Ageron 2003, p. 110.

- ↑ Khlifi, Omar (2005), L'assassinat de Salah Ben Youssef, Carthage: MC-Editions, p. 14

- ↑ Bessis & Belhassen 2012, p. 93.

- ↑ Chater, Khelifa (March 1, 2016). "Tunisie : 2 mars 1934, une date repère…!". L'Économiste maghrébin.

- ↑ Ounaies, Ahmed (2010). Histoire générale de la Tunisie, L'Époque contemporaine (1881–1956) (in French). 5. Tunis: Sud Editions., p. 402

- ↑ Le Pautremat & Ageron 2003, p. 90.

- ↑ L'encyclopédie nomade 2006, Paris: Larousse Edition, 2005, p. 708

- ↑ Ghorbal, Samy (June 17, 2007). "Que reste-t-il des grandes familles ?". Jeune Afrique.

References

- Boularès, Habib (2012). Histoire de la Tunisie. Les grandes dates, de la Préhistoire à la Révolution (in French). Tunis: Cerès Editions.

- Bessis, Sophie; Belhassen, Souhayr (2012). Bourguiba (in French). Tunis: Elyzad. ISBN 978-9973-58-044-3.

- Martel, Pierre-Albin (1999). Habib Bourguiba. Un homme, un siècle (in French). Paris: Éditions du Jaguar. ISBN 978-2-86950-320-5.

- Mestiri, Saïd (2011). Moncef Mestiri: aux sources du Destour (in French). Tunis: Sud Editions.

- El Materi Hached, Anissa (2011). Mahmoud El Materi, pionnier de la Tunisie moderne (in French). Paris: Les Belles Lettres.

- Le Pautremat, Pascal; Ageron, Charles-Robert (2003). La politique musulmane de la France au XXe siècle. De l'Hexagone aux terres d'Islam : espoirs, réussites, échecs (in French). Paris: Maisonneuve et Larose.

| Preceded by - |

Neo Destour Congresses | Succeeded by 1937 Court Street, Tunis |

.jpg)