La Luz del Mundo

Coordinates: 20°40′19.02″N 103°17′2.76″W / 20.6719500°N 103.2841000°W

| Iglesia del Dios Vivo, Columna y Apoyo de la Verdad, La Luz del Mundo (Church of the Living God, Column and Ground of the Truth, The Light of the World) | |

|---|---|

|

Logo of La Luz del Mundo Church | |

| Classification | Christian |

| Orientation | [1] |

| Structure | Hierarchical |

| Director | Naasón Joaquín García[2] |

| Region | 53 countries[3] as of August 2015 |

| Founder | Aarón (born Eusebio) Joaquín González |

| Origin |

1926[4][5] Guadalajara, Mexico |

| Separations | Iglesia del Dios Vivo, Columna y Apoyo de la Verdad, |

| Congregations | 2,869[3] as of August 2013 |

| Members | Between 1 and 7 million. See Statistics |

| Other name(s) |

Spanish: La Luz del Mundo; LLDM; LDM; Iglesia La Luz del Mundo; ILLM English: La Luz del Mundo Church; Church of the Living God, Column and Ground of the Truth, The Light of the World; The Light of the World Church |

| Official website |

www |

| Local Spanish pronunciation: [i´ɣlesja ðel djoz ´biβo, ko´lumna j a´poʝo ðe la βeɾ´ðað, la luz del ´mundo] | |

The Iglesia del Dios Vivo, Columna y Apoyo de la Verdad, La Luz del Mundo, (English: "Church of the Living God, Column and Ground of the Truth, The Light of the World")—or simply La Luz del Mundo—is a Christian denomination with international headquarters in Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico. La Luz del Mundo (abbreviated LLDM, or sometimes The LDM) practices a form of restorationist theology centered on three leaders: founder Aarón—born Eusebio—Joaquín González (1896–1964), Samuel Joaquín Flores (1937–2014), and Naasón Joaquin García (born 1969). These three men are regarded by the Church as modern day Apostles of Jesus Christ and Servants of God.

The Church had its beginnings in 1926 just as Mexico plunged into a violent struggle between the anti-clerical government and Catholic rebels. The conflict centered in the west-central states like Jalisco, where González focused his missionary efforts. Given the environment of the time, La Luz del Mundo remained a small missionary endeavor until 1934 when it built its first temple. Thereafter the Church continued to grow and expand, interrupted only by an internal schism in 1942. Apostles: Aarón Joaquín is believed to be designated the ministry of the Lord by revelation of God, then his son Samuel; thereafter by his son Naasón. The Church is now present in 50 countries and has between 1 and 7 million adherents worldwide.

La Luz del Mundo describes itself as the restoration of primitive Christianity. It does not use crosses or images in its worship services and its members do not observe Christmas or Holy Week. Female members follow a dress code that includes long skirts and head coverings during religious services.

Name

The full name of the Church is Iglesia del Dios Vivo Columna y Apoyo de la Verdad, La Luz del Mundo ("Church of the Living God, Column and Support of The Truth, The Light of The World") which is derived from two passages in the Bible, Matthew 5:14 and 1 Timothy 3:15.[6]

History

Historical background

Eusebio Joaquín González was born on August 14, 1896 in Colotlán, Jalisco. At a young age, he joined the Constitutional Army during the Mexican Revolution.[7][8] While he was on leave in 1920, he met Elisa Flores, whom he later married.[9] While stationed in the state of Coahuila in 1926, he came into contact with Saulo and Silas, two ascetic preachers from the Iglesia Cristiana Espiritual. Their teachings forbade their followers to keep good hygiene and wear regular clothes.[7] After being baptized by the two itinerant preachers, González resigned from the army, and along with his wife became domestic workers to the two preachers.[10]

During the 1920s, Mexico underwent a period of instability under the Plutarco Elías Calles administration who was seeking to limit the influence of the Catholic Church to modernize and centralize the state within the religious sphere of Mexican society. To protest the policies, the Catholic Church suspended all religious services, bringing about an uprising in Mexico. This uprising, or Cristero War, lasted from 1926 to 1929 and reemerged in the 1930s.[11] On April 6, 1926 González had a vision in which God changed his name from Eusebio to Aarón and was later told to leave Monterrey where he and his wife served Saulo and Silas.[12] On his journey, he preached near the entrances of Catholic churches—often facing religious persecution—until he arrived at Guadalajara on December 12, 1926.[10] The Cristero Wars impacted both Catholic and non-Catholic congregations and preachers, especially evangelical movements. Small movements were attacked by the government and the Cristeros, resulting in a hostile environment for González's work.[13]

Ministry of Aarón Joaquín González (1926-1964)

Early years

Working as a shoe vendor, González formed a group of ten worshipers who met at his wife's apartment.[14] He began constructing the Church's hierarchy by instituting the first two deacons, Elisa Flores and Francisca Cuevas.[15] Later he charged the first minister to oversee 14 congregations in Ameca, Jalisco.[16] During these early years (late 1920s), González traveled to the states of Michoacán, Nayarit, and Sinaloa to preach.[12] In 1931, the first Santa Cena (Holy Supper) was held to commemorate the crucifixion of Jesus.[17] The Church met in rural areas, fearing complaints from Catholic neighbors.[18] Urbanization contributed migrants from the countryside who added a significant amount of members to the Church.[18]

In 1934, a temple was built in Sector Libertad of Guadalajara's urban zone and members were encouraged to buy homes in the same neighborhood thereby establishing a community.[19] The temple was registered as Iglesia Cristiana Espiritual (Spiritual Christian Church) but González claimed to have received God's word in the dedication of the temple, saying that it was "light of the world" and that they were the Iglesia del Dios Vivo, Columna y Apoyo de la Verdad (Church of the Living God, Column and Ground of the Truth).[19] The Church used the latter name to identify itself.[19] In 1939, it moved to a new meeting place at 12 de Octubre street in San Antonio in southeast Guadalajara, forming its second small community which was populated mainly by its members.[20] This community was an attempt to escape the hostile environment,[21] not to create an egalitarian society.[22]

In 1938 González returned to Monterrey to preach to his former associates. There he learned that he had been baptized using the Trinitarian formula and not in the name of Jesus Christ as he preached.[19] His re-baptism in the name of Jesus Christ by his collaborator Lino Figueroa marked González's separation from the rest of the Pentecostal community.[19]

Schism of 1942

In 1942, in its most significant schism, at least 250 members left the Church.[23] Tensions began to build after González's birthday, when the congregation gave him gifts of flowers and sang hymns celebrating his birthday.[24] This celebration generated a heated debate that culminated with the defection of several church members, including some pastors.[24] Anthropologist Renée de la Torre described this schism as a power struggle in which González was accused of having enriched himself at the expense of the faithful.[23] Church dissidents took to El Occidental to accuse members of La Luz del Mundo of committing immoralities with young women. Some of the accusations were aimed to close down a temple that LLDM used with government permission.[25] Members of La Luz del Mundo attribute this episode to the envy and ambition of the dissidents, who formed their own group called El Buen Pastor (The Good Shepherd) under the leadership of José María González,[26] with doctrines and practices similar to those of La Luz del Mundo.[23] The leader is considered a prophet of God.[26] As of 2010, El Buen Pastor Church has a membership of 17,700 in Mexico.[27]

Among those who defected to El Buen Pastor Church was Lino Figueroa, the pastor who had re-baptized González in 1938. González had a vision in July 1943 where the baptism by Figueroa was invalidated and he was ordered to re-baptize himself invoking Jesus' name.[28] The whole congregation was re-baptized as well, as now González was the source of baptismal legitimacy and authenticity.[29] With all those who had challenged him gone, González was able to consolidate leadership of the Church.[24]

With the growth of the Church in the city, issues of safety developed in the 12 de Octubre street meeting place in the late 1940s and early 1950s. In 1952, González purchased a plot of land outside the city and called it Hermosa Provincia (Beautiful Province).[30]

Hermosa Provincia

In 1952, González purchased land on the outskirts of Guadalajara with the intent of forming a small community made up exclusively by members of LLDM.[31] The land was then sold at reduced prices to church members. The community included most necessities; services provided in Hermosa Provincia included health, education, and other urban services, which were provided in full after six years partly with help that the Church received from municipal and non-municipal authorities.[10] This dependency upon outside assistance to obtain public services ended by 1959 when residents formed the Association of Colonists of Hermosa Provincia, which was used to directly petition the government.[32] Hermosa Provincia received a white flag from the city for being the only neighborhood in the city that has eliminated illiteracy by the early 1970s.[33] González started missionary efforts in Central America and by the early 1960s, La Luz del Mundo had 64 congregations and 35 missions.[34] By 1964, after his death, the Church had between 20,000 and 30,000 members spread through five countries, including Mexico.[35][36] The neighborhood became a standard model for the Church which has replicated it in many cities in Mexico and other countries.[37]

Ministry of Samuel Joaquin Flores (1964-2014)

Samuel Joaquín Flores was born on February 14, 1937 and became the leader of the Church by the age of 27 after the death of González. He continued his father's desire for international expansion by traveling outside of Mexico extensively.[38] He first visited members of the Church in the Mexican state of Michoacán in August 1964 and later that year he went to Los Angeles on a missionary trip. By 1970, the Church had expanded to Costa Rica, Colombia, and Guatemala. The first small temple in the Hermosa Provincia was demolished and replaced by a larger one in 1967.[39] With Flores' work, La Luz del Mundo became integrated into Guadalajara and the Church replicated the model of Hermosa Provincia in many cities in Mexico and abroad. By 1972, there were approximately 72,000 members of the Church, which increased to 1.5 million by 1986 and to 4 million by 1993. Anthropologist Patricia Fortuny says that the Church's growth can be attributed to several factors, including its social benefits, which "improves the living conditions of believers."[40] Flores oversaw the construction of schools, hospitals and other social services produced by the Church.[41] It also expanded to countries including the UK, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Ethiopia and Israel between 1990 and 2010.[42] After fifty years at the head of La Luz del Mundo church, Flores died in his home on December 8, 2014.[43]

Ministry of Naasón Joaquín García (2014-present)

On December 14, 2014 Naasón Joaquín García, the fifth born of the Joaquin family, became the spiritual leader and international director of La Luz del Mundo church.[44] García was born on May 7, 1969 and previously served as pastor in Santa Ana, California.[45][46][47] After one year of arduous work García continues to lead the church, with ambition to fulfill a promise he received from God in a vision, that La Luz del Mundo Church will grow to a number that he could never imagine or perceive. He also urges the youth members of the church to join him in spreading their doctrine to the ends of the earth.

Beliefs and practices

Worship

During La Luz del Mundo's religious services, male and female members are separated during worship; from the preacher's perspective, women sit on the right side of the temple and men on the left.[48][49] The Church does not use musical instruments during its services.[50] There is no dancing or clapping,[51] and women cover their heads with a veil during worship services.[52] Hymns are sung a cappella;[53] Despite this, members listen to instrumental music and some have composed Christian music. When singing, all congregants sing at the same time. Congregations practice the songs to maintain proper melody and uniformity during their religious meetings.[54] The Church believes that worship should be done spiritually and only to God, and thus temples are devoid of images, saints, crosses, and anything that might be considered idolatry.[55] The places of worship have plain walls and wide, clear windows.[53]

The Church holds three daily prayer meetings during the week, with two meetings on Sundays and one regular consecration. On Sunday mornings, congregants meet at the temple for Sunday School, which begins with prayers and hymns. After that, the preacher—usually a minister—presides over a talk during which he reads from the Bible and presents the material to be covered throughout the week. During the talk, it is common for members of either sex to read a cited verse from the Bible. At the end of the talk, more hymns and prayers are recited and voluntary offerings are given. Sunday evening services begin with hymns and prayers, after which members of the congregation of both sexes recite from the Bible or sing hymns. A shorter talk is held with the aim of deepening the Sunday School's talk.[56]

The Church holds three scheduled prayer meetings each day. The first daily prayer meeting is at 5:00 a.m. and usually lasts one hour. The service includes a talk that is meant to recordar (remember) the material covered in the Sunday School. The 9:00 a.m. prayer was originally started by González's wife, Elisa Flores. A female church member presides over the prayer meeting, which includes a talk. The evening prayer has the same structure as the 5:00 a.m. meeting. In each prayer meeting members are expected to be prepared with their Bibles, hymn books and notebooks and to be consecrated.[57]

Bible

Members of La Luz del Mundo believe that the Bible along with the teachings of the Apostle are the only source of Christian doctrine. It is used as the source of ministers' and lay persons' talks during prayer meetings. Through organizational arrangements, such as Sunday school, church authorities attempt to maintain uniformity of teachings and beliefs throughout all congregations.[58] The Bible is the only historical reference used by La Luz del Mundo during religious services. Members can find cited Bible verses quickly, regardless of their level of education.[59] It is also seen as the one of two "sufficient rules of faith for salvation".[60]

Restorationism

La Luz del Mundo teaches that there was no salvation on Earth between the death of the last Apostle (Apostle John) around 96 AD and the calling of González in 1926. Members believe that the Church itself was founded by Jesus Christ approximately two thousand years ago and that after the deaths of the Apostles of God, the church became corrupt and was lost.[5][61] The Church claims that through González, it is the restoration of the Primitive Christian church that was lost during the formation of the Roman Catholic Church. After those times passed, the beginning of González's ministry is seen as the restoration of the original Christian Church.[62] Salvation can be attained in the Church by following the Bible-based teachings of their leader.[63]

Calling of the Servants of God

The Church states that its members believe in "the calling of the Servants of God, sent to express the will of God and Salvation".[64] It believes that González was called by God to restore the Primitive Christian Church. González was succeeded by Flores upon his death in 1964; Flores was in turn succeeded by García upon his death in 2014. La Luz del Mundo teaches that it is the only true Christian church founded by Jesus Christ because it is led by García, who it considers the only true servant of God and Apostle of Jesus Christ in this era.[5] Members believe that this Apostolic Authority allows them to find peace, feel close to God and attain meaning in their lives from the hopes of joining with Christ to reign with him for eternity.[65]

Christology

La Luz del Mundo rejects the doctrine of the Trinity as a later addition to Christian theology.[66] It believes in a "one and universal" God and in Jesus Christ who is the "Son of God and Savior of the world", rather than part of a trinity.[55][67] God is worshiped "by essence", whereas Jesus is worshiped "by commandment."[68] Moreover, by worshiping Jesus Christ they are also worshiping God through him according to their teachings.[69] The Church also preaches baptism in the name of Jesus Christ for forgiveness of sins, and baptism with the Holy Spirit as confirmation from God for entrance into heaven.[67]

There is disagreement among external sources regarding the christology of La Luz del Mundo. According to theologian Roger S. Greenway, the Church is trinitarian but baptizes in the name of Jesus to conform to apostolic practice.[70] Theological librarian Kenneth D. Gill agrees with Greenway that the Church is trinitarian, and says it refuses to "use the term 'person' to describe the three modes of God."[71] Sociocultural anthropologist Hugo G. Nutini also says the Church is trinitarian but that its worship focuses exclusively on Jesus Christ as the source of salvation.[72]

Role of women

In the tradition of Pentecostalism, female members of La Luz del Mundo do not wear jewelery or makeup and are instructed to wear full, long skirts.[73] Women can have their hair as short as their shoulder blades. These restrictions do not apply to recreational activities, where wearing bathing suits is permitted.[74] Women wear a head covering during religious meetings.[75] According to an interview of one adherent, women in the Church are considered equal to men in social spheres and have equal capacities for obtaining higher education, social careers, and other goals that may interest them.[76]

González established the 9 a.m. prayer after hearing about one of his followers who was being abused by her Catholic husband.[77] This prayer became one led by women.[77] These prayers are seen as a religious activity equal to all other activities.[78] This prayer provides space for empowerment in which women can express themselves and develop a status within the congregation's membership.[79] Anthropologist Patricia Fortuny said, concerning the 9 a.m. prayer, that, "I infer from this that, if the membership considers this as [a] female [gathering], they would be giving authority to women in the religious or ecclesiastical framework of the ritual, and this then [would] put [them] on a plane of equality or [in] absence of subordination to men."[80] She said that women of the Church may be playing with their subordinate roles in the Church to acquire certain benefits.[80]

Church women personalize their attire, according to Patricia Fortuny. Rebozos are worn by indigenous members and specially designed veils by other female members.[81] Fortuny says that, "... wearing long skirts does not negate the meaning of being a woman and, although it underlines the difference between men and women, [the Church's female members] say that it does not make them feel like inferior human beings".[82] Fortuny says women describe their attire as part of obeying biblical commands found in 1 Timothy 2:9, and 1 Corinthians 11:15 for long hair.[83] Female members say the Church's dress code makes them feel they are honoring God and that it is part of their "essence".[84]

Fortuny also states that dress codes are a sign of a patriarchal organization because men are only forbidden from growing their hair long or wearing shorts in public. Women, at times, can be more autonomous than those in the general population in Mexico. Fortuny says that the growing trend of educated women having husbands in supporting roles is also seen within the Church both in the Guadalajara (Mexico), and Houston (Texas) congregations.[85] Many young female members said they want to undergo post-secondary education, and some told Fortuny they were degree students. Both young men and women are equally encouraged to enter post-compulsory education. Fathers who are members of La Luz del Mundo are more likely than their mothers to direct their daughters towards attending university.[86]

La Luz del Mundo Church does not practice ordination of women. According to Fortuny, women can become missionaries or evangelizers; the lowest tier of the Church's hierarchy.[87] She states that "the rank of deaconess is not a position which common women could aspire to".[88] Dormady states that the first two deaconesses were Elisa Flores and Francisca Cuevas.[15] Wives of important members of the Church usually get the rank of deaconess, according to Dormady.[89][90]

Women are active and play key roles in organizing activities and administering them in the Church.[73] Female office holders are always head of groups of women and not groups of men. A deaconess can help pastors and deacons, but cannot herself administer the sacrament. All members of the ministerial hierarchy are paid for their services as part of the tithe by the congregational members.[91]

At the turn of the century, La Luz del Mundo Church began promoting women to public relations positions that were previously held by men only.[92] As of December 2014, two women (and three men) serve as legal representatives of the church in Northern Mexico.[93] Public relations positions that have been held by women include spokesperson, director of social communication, and assistant director of international affairs.[94][95][96] Within church operated civil organizations women also occupy executive positions such as director of La Luz del Mundo Family Services, a violence prevention and intervention center in South Side, Milwaukee;[97] Director of Social Work and Psychology within the Ministry of Social Welfare;[98] director of the Samuel Joaquín Flores Foundation; president of Recab de México A.C.;[99] and director of the Association of Students and Professionals in the USA.[100]

Other beliefs and practices

The Church teaches moral and civil principles such as community service and that science is a gift from God.[67] Members of La Luz Del Mundo do not celebrate Christmas or Holy Week. The most important yearly rituals are the Holy Supper (Santa Cena in Spanish or "Santa Convocation"), held yearly on August 14, and the anniversary of García's birth is held on May 7 at its international headquarters in Guadalajara.[101]

Organization

Ecclesiastical organization

The organization of La Luz del Mundo is apostolic. The head of the Church is Jesus Christ and in his representation is Naason Joaquin García, who is the "Apostle and Servant of God" and the organizational authority as General Director of the Church. Below him is the ranks of pastors, who are expected to develop one or more of the qualities as doctor, prophet, and evangelist. All pastors are evangelists and are expected to undertake missionary tasks. As doctors, pastors explain the word of God and as prophets they interpret it.[102] Below them are the deacons, who administer the sacraments to the congregational members. Below the deacons are the encargados (managers or overseers), who have responsibility for the moral conduct and well-being of certain groups within the congregation. Overseers grant permits to members who wish to leave their congregations for vacations or to take jobs outside of the church district. At the lowest echelon of the hierarchy are the obreros (laborers), who mainly assist their higher-ups with missionary work.[103]

Territorial organization

A church, or group, that is unable to fully provide for the religious needs of its members is called a mission. Missions are dependent on a congregation which is administered by a minister. A group of several congregations with their missions form a district. The Church in each nation is divided into multiple districts. In Mexico, several districts form together into five jurisdictions that act as legal entities.[104]

Architecture

La Luz del Mundo uses the architecture of its temples to express its faith through symbolism and to attract potential converts.[105][106][107] Among the Church's buildings are a replica of a Mayan pyramid in Honduras, a mock Taj Mahal in Chiapas, Mexico, and a Greco-Roman-inspired temple in California. Its flagship temple is located in its headquarters in Hermosa Provincia. Two smaller replicas of this temple are being built in Anchorage, Alaska, and in Chile to symbolize "the northern and southern-most reach of the Church's missionary efforts."[106]

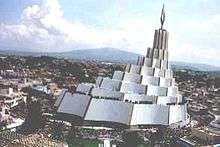

Hermosa Provincia Temple

The flagship temple in Guadalajara is pyramidal and has an innovative structure. The project began in 1983, when the Church's former temple built to accommodate 8,000 people was deemed insufficient to accommodate the growing number of people who attended various annual celebrations.[108] Construction began on July 3, 1983 when Flores laid the cornerstone and lasted until August 1, 1992.[109] The temple was completed largely by members of the Church. It is a notable architectural feature in Guadalajara in a working-class district on the outskirts of the city. Dozens of institutions, architects, and engineers were invited to submit proposals for a new temple. The pyramidal design submitted by Leopoldo Fernández Font was from the final shortlist of four proposals.[108] Fernandez Font was later awarded an honorary degree for this and other structures. He said that one of his favorite works is the Temple of the Resurrection, but that the temple of La Luz del Mundo seemed difficult to him.[110] The temple was built to accommodate 12,000 worshipers and is used for annual ceremonies.

The building's design represents the infinite power and existence of God. It consists of seven levels over a base menorah, each of which symbolize steps toward the human spirit's perfection.[108] In February 1991, a laser beacon was installed to commemorate the 449-year anniversary of the founding of Guadalajara.[111] On July 1999 the pinnacle of the temple "La Flama" was replaced by Aaron's rod, a twenty-ton bronze sculpture by artist Jorge de la Peña. The installation of the 23-metre (75 ft) long structure required a special crane.[112][113]

Houston Texas Temple

The main temple in Houston, Texas, was inspired by Greco-Roman architecture.[114] It is the largest temple constructed by La Luz del Mundo in the United States as of 2011. The temple's pillars resemble the Parthenon, according to religious historian Timothy Wyatt. The front of the building is decorated with carved scenes from the Bible and three panes of stained glass also depict biblical scenes. The temple can hold 4,500 people. The interior has marble floors, glass chandeliers, and wood paneling.[114]

The structure is worth US$18 million and consists of the temple, classrooms, offices, and a parsonage. There is a sitting area with 14 free-standing columns in a circle next to the temple.[115] Each column represents each of the Apostles—including Aarón and Samuel Joaquín.[114] On top of the temple under Aaron's rod—the Church's symbol which represents God's power tobring spiritual life to believers—is a large, golden dome.[114][115] The symbol is also a reference to the Church's founder.[115]

Construction of the temple began in 2000 and it was finished in 2005. Most of the construction was done by Church volunteers, who provided funding and a skilled workforce.[115][114] The structure was designed by Church members and the design was revised by architects to ensure compliance with building codes.[115] The decorations and ornaments were also designed and installed by Church members.[115] The temple serves as a central congregation for southeastern Texas.[114][116]

Statistics

There are no definitive statistics for the total membership of La Luz del Mundo.[37] It has reported having over five million members worldwide in 2000 with 1.5 million in Mexico. The Church does not appear in the 1990 Mexican census or any census prior to that.[117]

The 2000 Mexican census reported about 70,000 members nationwide,[118][119] and the 2010 census reported 188,326 members.[120] The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, whose numbers also differ significantly from those of the census—1,234,545 compared to the census figure of 314,932—said ambiguity in the census questionnaire was the source of the disparity.[121] The World Christian Encyclopedia reports 430,000 adherents in Mexico in 2000 and 488,000 in Mexico in 2010.[122] Anthropologist Hugo G. Nutini estimated that the Church had around 1,125,000 members in 2000 in Mexico.[37] In 2008, Fortuny and Williams estimated the membership at 7,000,000.[123] Anthropologist Ávila Meléndez says that the membership numbers reported by La Luz del Mundo are plausible given the great interest it has generated among "religious authorities" and the following it receives in Mexico.[119]

In El Salvador, as of 2009, there are an estimated 70,000 members of La Luz del Mundo, which had 140 congregations with a minister and 160 other congregations with between 13 and 80 members.[124] As of 2008, there were around 60,000 members of the Church in the United States.[125]

Controversy

In the wake of the Heaven's Gate mass suicide, La Luz del Mundo found itself embroiled in a controversy that would play out in some of Mexico's major media outlets.[126][127][128] Former members and anti-cult groups leveraged accusations against the church and its leadership.[126][127] Church members and sympathizers defended the integrity of the church.[127] Academics, meanwhile, denounced a climate of intolerance toward religious minorities in Mexico.[127]

Allegations of potential for mass suicide

Following the Heaven's Gate mass suicide on March 26, 1997, Mexican journalists asked which religious group at home could stage similar acts.[126][129] The following day, in TV Azteca's flagship program, Jorge Erdely Graham leader of the obscure anti-cult group Instituto Cristiano de Mexico (Christian Institute of Mexico) pointed to La Luz del Mundo as a group with the potential to commit mass suicide.[126] Erdely's claims were based on an interview with three church members conducted two years earlier.[129] La Luz del Mundo denied the claims arguing that the answers of three individuals cannot be used to make generalizations about an entire community.[129] Religious scholars Gordon Melton and David Bromley characterized the accusations as "fraudulent reports by ideological enemies."[130] Anthropologist Elio Masferrer Kan criticized the methodology employed in the interview, noting that the interviewer cornered the subjects to obtain the desired response.[129]

This incident focused media attention on the church,[126] and in May 4, 1997 the accusations were broadcast on Mexico's most-watched newscast on Televisa.[131]

Sexual abuse accusations against Flores

On May 18, 1997 (a day after Flores' 35th wedding anniversary)[132] in a follow-up report on Televisa, a handful of women claimed to have been sexually abused by Flores approximately twenty years earlier.[133] In a third report on August 17, shortly after the church's most significant holiday, former member Moisés Padilla Íñiguez also accused Flores of sexually abusing him when he was a teenager.[133][127] These accusations were spearheaded by Erdely's anti-cult group, which demanded that La Luz del Mundo be stripped of its legal recognition as a religious organization.[134][135] Four people later filed formal complaints with the state prosecutor, but the statute of limitations for the alleged crimes had passed.[126]

The issue came back to life in February of the following year when, two days before Flores' birthday, Padilla reported being kidnapped and stabbed by two gunmen.[126][136][137] Padilla received 57 shallow slashes from a dagger which did not put his life in danger,[136] but he could have died from blood loss.[126] Padilla blamed Flores for the stabbing and for an earlier attack in which he was allegedly beaten by men who warned him against criticizing the church leader.[126] A church spokesman denied that the Church or Flores had any involvement in the attack and suggested that Padilla may have orchestrated the attack in a desperate attempt to authenticate his previous charges against the Church.[126][137]

Judicial authorities investigating the charges said the alleged victims were not being fully cooperative, whereas former members were suspicious of the Mexican legal system, arguing that it favored the church.[126] Ten years later a spokesman for the state prosecutor said the criminal complaints were unsuccessful because, in addition to the statute of limitations, the accusations were unfounded.[138]

Sociologist Roberto Blancarte called the controversy a "persecution" fueled by "obscure interests."[139] Journalist Carlos Monsiváis described the issue as a diffamation campaign.[140] Sociologist Bernardo Barranco described it as a dirty war that was well exploited by the media.[141][142] Anthropologist Carlos Garma Navarro criticized that the accusations were first brought before the mass media, and thought it was very likely that the accusations were an attempt to give the church a bad image.[143][144] Journalist Gastón Pardo called it a smear campaign characterized by the systematic use of defamation and slander.[145]

Discrimination

Opposition to new temple in California

In 1995, La Luz del Mundo acquired a vacant nursery building in a commercial zone in Ontario, California. The Church planned to use it for religious activities and was assured that it could as long as building requirements were met. The city then passed a law requiring all new religious organizations to obtain a conditional use permit to operate a church in the commercial zone.[146] In 1998, the Church petitioned for such a permit but concerned residents objected to its plans.[138] María de Lourdes Argüelles, professor at Claremont Graduate University and board member of the Instituto Cristiano de México,[147] led the opposition against the Church, which she called a "destructive sect".[126] She said she had seen children and teenagers working overnight on the site under precarious conditions.[148]

Ontario officials met with objecting residents and began researching the Church and checking with cities where Luz del Mundo had temples, but found no problems.[126] After considering zoning questions and citing traffic, parking and disruption of economic plans for that area, the city denied the permit to the Church. La Luz del Mundo then sued the city for denying it use of its own building for services and for allegedly violating its civil rights. The case was settled out of court in 2004, and the Church was allowed to build the temple.[138] The city agreed to pay about US$150,000 in cash and fee credits to the Church.[146] The case was not taken to court because city officials and attorneys concluded the city would most likely lose the case and spend more money than the settlement.[146]

Denominational Discrimination

According to Patricia Fortuny, members of La Luz del Mundo along with members of other Protestant denominations, are treated as "second class citizens".[149] She says the Church is called a sect in an offensive manner in Mexico.[150] Rodolfo Morán Quiroz, a sociologist, said that the discrimination started by the Catholic Church, which in the past caused La Luz del Mundo to seek help from the authorities who promoted religious freedom in establishing its community in Hermosa Provincia, continues in Mexico.[151] Church founder González was beaten by Cristeros and was jailed by the government for preaching in the open air.[152]

In 1995, as thousands of members of the Church traveled to the Holy Supper celebration in Guadalajara, several members of a neighboring community supported by Cardinal Juan Sandoval Íñiguez protested the use of schools to provide temporary shelters for the Luz del Mundo pilgrims. The protesters said that after the ceremony the schools were left in disarray; however church authorities presented photographic evidence to newspapers to refute these claims.[153]

According to Armando Maya Castro, many students who are members of the Church have been discriminated against for refusing to partake in celebrations and customs concerning the Day of the Dead in their schools, and some have been punished for it.[154] In one case reported by a Mexican newspaper, La Gaceta, a female member of the Church was pushed by a fellow bus passenger, who then crossed herself because the member was wearing a long skirt.[155] In July 25, 2008, a public official sealed the entrance to a La Luz del Mundo temple in Puerto Vallarta, Jalisco, trapping the congregation inside until other officials removed the seals. This incident occurred because of complaints from individuals who did not like the presence of the Church in the area. Reporter Rodolfo Chávez Calderón stated the Church was in compliance with local laws.[156]

Many female church members have faced discrimination and verbal abuse on buses, schools, and hospitals.[157] Church members who were patients in a Mexican hospital were denied access to their ministers in 2011. The hospital required permission from Catholic clergy so that LLDM ministers could visit patients.[158]

Ministers of the Church reported that the site of a newly constructed temple in Silao was subject to harassment of its members, vandalism, and physical threats because of religious intolerance, which caused them to request increased police protection.[159][160] In February 2012, seventy ministers of La Luz del Mundo from different nations appeared before Mexican authorities in Guadalajara to denounce the lack of police protection for the Church's residents in the city after a series of attacks left several members hospitalized.[161]

Notes

- Citations

- ↑ Fortuny 1995, pp. 147-162.

- ↑ García, Omar (14 December 2014). "Naasón Joaquín García relevará a su padre en la Luz del Mundo" [Naasón Joaquín García will relieve his father in La Luz del Mundo]. El Informador (in Spanish). Guadalajara. Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- 1 2 "Ceremonia de Bienvenida" (in Spanish). Iglesia del Dios Vivo Columna y Apoyo de la Verdad, La Luz del Mundo. 9 August 2013. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ↑ "Historia". Iglesia del Dios Vivo Columna y Apoyo de la Verdad, La Luz del Mundo. Retrieved 25 December 2012.

- 1 2 3 "Fundación" (in Spanish). Iglesia del Dios Vivo Columna y Apoyo de la Verdad, La Luz del Mundo. Retrieved 25 December 2012.

- ↑ De la Torre 2000, p. 77.

- 1 2 De la Torre 2000, p. 71.

- ↑ Pineda, Israel (14 November 2008). "Homenaje. Historia Militar: Mtro. Aarón Joaquín González. 90 Años de haber alcanzado el grado de subteniente de infantería". La Luz del Mundo USA (in Spanish). Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- ↑ Dormady 2011, p. 22.

- 1 2 3 Fortuny 1995, p. 149.

- ↑ Fortuny 1995, p. 148.

- 1 2 De la Torre 2000, p. 73.

- ↑ De la Torre 2000, pp. 73-74.

- ↑ Dormady 2011, p. 28.

- 1 2 Dormady 2011, p. 35.

- ↑ Dormady 2011, pp. 36-37.

- ↑ Dormady 2011, p. 34.

- 1 2 Dormady 2011, p. 37.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Dormady 2011, p. 38.

- ↑ Dormady 2011, pp. 39-40.

- ↑ Dormady 2011, p. 41.

- ↑ Dormady 2011, p. 42.

- 1 2 3 De la Torre 2000, p. 80.

- 1 2 3 Dormady 2011, p. 43.

- ↑ Dormady 2011, pp. 42-45.

- 1 2 Gill 1994, p. 277.

- ↑ Johnson, Todd M.; Grim, Brian J., eds. (2007). World Christian Database. Leiden/Boston: Brill.

- ↑ Dormady 2011, pp. 42–44.

- ↑ Dormady 2011, p. 44.

- ↑ Dormady 2011, pp. 46–47.

- ↑ De la Torre 2000, p. 81.

- ↑ Dormady 2011, pp. 50-51.

- ↑ Greenway 1973, p. 118.

- ↑ Fortuny 1995, p. 150.

- ↑ Joaquín 2004, p. 104.

- ↑ Greenway 1973, p. 121.

- 1 2 3 Nutini 2000, p. 47.

- ↑ Fortuny 1995, p. 151.

- ↑ Joaquín 2004, p. 61,67.

- ↑ Fortuny 1996, pp. 33–37.

- ↑ De la Torre 2000, p. 87.

- ↑ Joaquín 2004, p. 71.

- ↑ "Boletín informativo: Duerme en los brazos de Cristo el Apóstol Samuel Joaquín Flores" (Press release) (in Spanish). Guadalajara, Jalisco: Iglesia La Luz del Mundo A.R. 8 December 2014. Retrieved 2014-12-31.

- ↑ García, Omar (14 December 2014). "Naasón Joaquín García relevará a su padre en la Luz del Mundo". El Informador (in Spanish). Guadalajara. Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- ↑ "Eligen a director internacional de La Luz del Mundo". La Crónica de Hoy. Jalisco. 14 December 2014. Retrieved 31 December 2014.

- ↑ Torres, Raúl (17 December 2014). "Luz del Mundo: un líder del que poco se conoce". El Universal. Mexico City. Retrieved 31 December 2014.

- ↑ "Primer Presentación Apostolica en el Extranjero". Iglesia La Luz del Mundo USA. 4 January 2015. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- ↑ Wyatt 2011, p. 9.

- ↑ Ravitz, Jessica (2 August 2008). "Hallelujah: Spirit and emotion run high at The Light of the World Church". The Salt Lake Tribune. Retrieved 12 January 2013.

- ↑ De la Torre 2000, p. 244.

- ↑ Ochoa Bohórquez 2011, pp. 122.

- ↑ De la Torre, Renée; Fortuny, Patricia (1991). "La mujer en "la luz del mundo" Participación y representación simbólica". Estudios sobre las culturas contemporáneas (in Spanish). Universidad de Colima. IV (12): 137–138. ISSN 1405-2210. OCLC 819025679.

- 1 2 Mink, Jenna (5 August 2011). "Congregation blossoms: Church catering to Hispanic community grows in BG". Bowling Green Daily News. Retrieved 12 January 2013.

- ↑ Ochoa Bohórquez 2011, pp. 121-123.

- 1 2 Peggy Fletcher Stack (24 May 2013). "For this Salt Lake City church, it's the beliefs, not the building, that matter". The Salt Lake Tribune. Retrieved 16 July 2013.

- ↑ Ochoa Bohórquez 2011, pp. 139-142.

- ↑ Ochoa Bohórquez 2011, pp. 142-148.

- ↑ Ávila Meléndez 2008, pp. 180–181,187.

- ↑ Ochoa Bohórquez 2011, p. 147.

- ↑ "Doctrina" (in Spanish). Iglesia del Dios Vivo Columna y Apoyo de la Verdad, La Luz del Mundo. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

CREEMOS en la Santa Biblia como única y suficiente regla de fe para la salvación del ser humano ...

- ↑ Ávila Meléndez 2008, p. 177.

- ↑ Ochoa Bohórquez 2011, p. 150.

- ↑ Biglieri 2000, p. 407.

- ↑ "Principios" (in Spanish). Iglesia del Dios Vivo Columna y Apoyo de la Verdad, La Luz del Mundo. Retrieved 18 January 2013.

CREEMOS en la vocación de los Siervos de Dios, enviados para manifestar la voluntad de Dios y la Salvación.

- ↑ "Historia" (in Spanish). Iglesia del Dios Vivo Columna y Apoyo de la Verdad, La Luz del Mundo. Retrieved 18 January 2013.

- ↑ "¿Qué es La Luz del Mundo?". 23 June 2010.

- 1 2 3 "Principios" (in Spanish). Iglesia del Dios Vivo Columna y Apoyo de la Verdad, La Luz del Mundo. Retrieved 18 January 2013.

- ↑ Amaya Castro, Armando (4 July 2010). "Sobre Una conmemoración político-religiosa". Proceso (in Spanish). Mexico City. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- ↑ "Presentación apostólica en Cancún, Quintana Roo". 19 April 2015.

- ↑ Greenway 1973, p. 119.

- ↑ Gill 1994, p. 275.

- ↑ Nutini 2000, p. 48.

- 1 2 Wyatt 2011, pp. 26–29.

- ↑ Fortuny, pps. 126, 149–150

- ↑ Fortuny 2001, p. 125.

- ↑ Fortuny 2001, pp. 133-134.

- 1 2 Dormady 2011, p. 33.

- ↑ Fortuny 2001, p. 139.

- ↑ Fortuny 2001, p. 144.

- 1 2 Fortuny 2001, p. 140: "Yo deduzco de esto que, si la membresía considerara este culto como femenino, le estarían otorgando autoridad a las mujeres en el marco religioso o eclesiástico del ritual, y esto entonces las pondría en un plano de igualdad o de ausencia de subordinación frente a los hombres"

- ↑ Fortuny 2001, p. 148.

- ↑ Fortuny 2001, p. 149: "En este sentido, usar falda larga no niega el significado del ser mujer y aunque subraye la diferencia entre hombres y mujeres, ellas dicen que no las hace sentirse seres humanos inferiores ..."

- ↑ Fortuny 2001, p. 142.

- ↑ Fortuny 2001, pp. 146–147.

- ↑ Fortuny 2001, pp. 156–157.

- ↑ Fortuny 2001, pp. 155–157.

- ↑ Fortuny 2001, p. 136: "Al interior del cuerpo ministerial o jerarquía de la iglesia, la mujer puede ocupar el puesto obrera o evangelizadora si así lo desea, ya que constituye el último rango de la jerarquía."

- ↑ Fortuny 2001, p. 138: "el rango de diaconisa no es una posición a la que puedan aspirar las mujeres comunes de la comunidad religiosa ..."

- ↑ Dormady 2011, pp. 35–36.

- ↑ Pineda, Israel (25 March 2009). "Duerme la diaconisa Carmen Flores viuda de Ávalos". Iglesia La Luz del Mundo USA (in Spanish). Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- ↑ Fortuny 1995, p. 157.

- ↑ Garma Navarro, Carlos (2004). "The Legal Situation of Religious Minorities in Mexico: The Current situation, Problems, and Conflicts". In James T. Richardson. Regulating Religion: Case Studies from Around the Globe. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. p. 446. ISBN 978-0-306-47886-4. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- ↑ "Directorio de Asociaciones Religiosas por Clave SGAR" (PDF) (in Spanish). Mexico: Dirección General de Asociaciones Religiosas de la Secretaría de Gobernación. pp. 58–59. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- ↑ Gómez, Alejandra; Rebolledo, Antonio (12 May 2014). "Con mantas blancas concluye grupo religioso mensaje en cerro". El Diario (in Spanish). Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- ↑ "Luto en Tabasco tras la tragedia en Cumbres de Maltrata". Proceso. Mexico City. 19 April 2006. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- ↑ Dormady 2011, pp. 39.

- ↑ O'Brien, Brendan (29 August 2013). "La Luz del Mundo opens violence prevention center on South Side". Milwaukee Neighborhood News Service. Milwaukee. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- ↑ "Ha llegado ya el 50% de los delegados a la Santa Convocación 2008". Iglesia La Luz del Mundo. 7 August 2008. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- ↑ "Realiza la Fundación Samuel Joaquín Flores rueda de prensa para evento benéfico". Iglesia La Luz del Mundo. 4 February 2010. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- ↑ "Reconocimiento de APS a los graduados de la clase 2010 en el Sur de California". Iglesia La Luz del Mundo. 17 July 2010. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- ↑ Biglieri 2000, p. 409.

- ↑ Fortuny 1995, p. 155.

- ↑ Fortuny-Loret de Mola, Patricia (2005). "Una iglesia tapatía: evangélica, popular y transnacional". Los "otros" hermanos : minorías religiosas protestantes en Jalisco (in Spanish). Guadalajara, Jalisco: Secretaría de Cultura, Gobierno del Estado de Jalisco. p. 176. Retrieved 8 October 2013.

- ↑ "Organización" (in Spanish). Iglesia del Dios Vivo Columna y Apoyo de la Verdad, La Luz del Mundo. Retrieved 18 January 2013.

- ↑ Kaylin Bettinger (9 July 2010). "After 4 years, 'wedding cake' is only half-baked". Anchorage Daily News. Retrieved 17 November 2012.

- 1 2 Julia O'Malley (30 March 2008). "Church constructs unusual building to attract converts". Anchorage Daily News. Retrieved 17 November 2012.

- ↑ Pela, Robrt L. (4 November 2010). "La Luz del Mundo: God May Not Live in a Material Church, But He's Building a Sweet Pad". Phoenix New Times. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- 1 2 3 Noriega, Ariel (August 13, 2000). "Templo de la Luz: Símbolo y orgullo". Mural (in Spanish). Guadalajara, Mexico. p. 5.

- ↑ Muñoz, Joel (April 6, 2001). "Luz del Mundo influencia en 33 países". Mural (in Spanish). Guadalajara, Mexico. p. 8.

- ↑ Alvarado, Alejandro (September 10, 2009). "Honran colegas un estilo humano". Mural (in Spanish). Guadalajara, Mexico. p. 6.

- ↑ Pineda, Israel (31 August 2000). "Cartas a Mural/ Sobre el templo de La Luz del Mundo". Mural (in Spanish).

- ↑ "Estrenan símbolo". Mural (in Spanish). Guadalajara, Mexico. July 14, 1999. p. 1.

- ↑ "Una escultura de peso". Mural (in Spanish). Guadalajara, Mexico. July 1, 1999. p. 1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Wyatt 2011, pp. 26-29.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Vara, Richard (23 July 2005). "La Luz del Mundo prepares to dedicate new church facility". The Houston Chronicle. Houston.

- ↑ Fortuny 2002, p. 24.

- ↑ "Censo General de Población y Vivienda 1990" (in Spanish). Mexico: Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- ↑ Dormady 2011, p. 115.

- 1 2 Ávila Meléndez 2008, p. 180.

- ↑ "Población total por entidad federativa, sexo y religión según grupos de edad (INEGI 2010)" (in Spanish). Mexico: Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. Retrieved 21 September 2012.

- ↑ "¿Cuantos mormones hay en México?". Sala de Prensa - México (in Spanish). Iglesia de Jesucristo de los Santos de los Últimos Días. 28 March 2012. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- ↑ Johnson, Todd M.; Grim, Brian J., eds. (2007). World Christian Database. Leiden/Boston: Brill.

- ↑ Fortuny and Williams 2008, p. 15

- ↑ Alfaro, William (21 December 2009). "La Iglesia Evangélica gana más terreno en El Salvador". El Diario de Hoy (in Spanish). El Salvador. Retrieved 21 September 2012.

- ↑ Marquardt 2011, p. 119.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Sheridan, Mary Beth (10 March 1998). "A Growing Faith--and Outrage". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 23 September 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 De la Torre 2000, p. 19.

- ↑ Barranco, Bernardo (29 December 1997). "Balance religioso en 1997". La Jornada (in Spanish). Mexico City. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Masferrer Kan 2004, p. 156.

- ↑ Bromley & Melton 2002, p. 50.

- ↑ Masferrer Kan 2004, p. 161.

- ↑ García de la Mora, Humberto (6 January 2014). "2014: Año del Jubileo". El Occidental (in Spanish). Guadalajara. Retrieved 25 December 2014.

- 1 2 Masferrer Kan 2004, p. 164.

- ↑ Garma Navarro, Carlos (1999). "La situación legal de las minorías religiosas en México: Balance actual, problemas y conflictos". Alteridades (in Spanish). Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana - Iztapalapa. 9 (18): 141–142. ISSN 0188-7017. OCLC 31126010. Retrieved 25 December 2012.

- 1 2 Salas, Irma (11 February 1998). "Atacan a denunciante de la Luz del Mundo". El Norte (in Spanish). Monterrey, Mexico.

- 1 2 "Church denies knife connection" (PDF). Laredo Morning Times. 12 February 1998. p. 2A. Retrieved 25 December 2012.

- 1 2 3 Bensman, Todd (25 May 2008). "Divine Retreat". San Antonio Express-News. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- ↑ Blancarte, Roberto (2002). "Religiones y creencias en México" (PDF). Revista Este País. Desarrollo de Opinión Pública: 112. Retrieved 18 January 2013.

- ↑ Monsiváis 2002, p. 86.

- ↑ Barranco, Bernardo (29 December 1997). "Balance religioso en 1997". La Jornada. Retrieved 12 January 2013.

- ↑ Barranco, Bernardo (17 December 2014). "La Luz del Mundo". La Jornada (in Spanish). Mexico City. Retrieved 25 December 2014.

- ↑ Garma Navarro, Carlos (2004). Buscando el espíritu: Pentacostalismo en Iztapalapa y la ciudad de México. Plaza y Valdés. p. 172. ISBN 978-970-722-280-9.

- ↑ Pardo, Gastón (13 August 2005). "Los responsables están avalados por el gobierno". Voltaire Network. Retrieved 12 January 2013.

A lo largo de 1997, una secta denominada Instituto Cristiano de México lanzó ataques en los medios informativos en contra de líderes religiosos, a quienes intentó desacreditar con el empleo sistemático de difamaciones y calumnias.

- 1 2 3 Gazzar, Brenda (10 February 2005). "Ontario clears way for La Luz Del Mundo". Inland Valley Daily Bulletin.

- ↑ "María de Lourdes Argüelles". School of Educational Studies. Claremont Graduate University. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- ↑ Masferrer Kan 2004, p. 153.

- ↑ Fortuny 2002, pp. 25–26.

- ↑ Fortuny 2002, p. 33.

- ↑ Munez Machuca, Aimee (3 March 2003). "Mantiene la Hermosa provincia su autonomía sin aislamientos" (PDF). Gaceta Universitaria (in Spanish). Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- ↑ Miller, Daniel R (2008). "Protestantism and Radicalism in Mexico from the 1860s to the 1930s". Fides et Historia. The Conference on Faith and History. 40 (1): 43–66. ISSN 0884-5379.

- ↑ Fortuny, Patricia (2000). "La Luz del Mundo, estado lacio y gobierno panista. Análisis de una coyuntura en Guadalajara" (PDF). Espiral: Estudios sobre Estado y Sociedad (in Spanish). Universidad de Guadalajara. 7 (19): 129–159. ISSN 1665-0565. OCLC 32365060. Retrieved 20 October 2012.

- ↑ Castro, Armando Maya (18 April 2011). "La discriminación religiosa, una realidad en México". El Universal (in Spanish). Retrieved 20 October 2012.

- ↑ Loera, Martha Eva (28 August 2006). "Las variantes de la fe" (PDF). La Gaceta (in Spanish). Universidad de Guadalajara. Retrieved 20 October 2012.

- ↑ Chávez Calderón, Rodolfo (25 July 2008). "Clausuraron templo de la Iglesia de La Luz del Mundo en Vallarta". El Occidental (in Spanish). Retrieved 5 November 2012.

- ↑ Fortuny, pps. 150–154

- ↑ Rello, Maricarmen (13 August 2009). "Hospital Civil se disculpa con Luz del Mundo". El Milenio (in Spanish). Retrieved 20 October 2012.

- ↑ Álvarez, Xóchitl (18 January 2012). "Piden prevenir brote de intolerancia religiosa". El Universal (in Spanish). Retrieved 20 October 2012.

- ↑ "Religion in Mexico: Where angels fear to tread". The Economist. 24 March 2012. Retrieved 12 January 2013.

- ↑ "Ministros de La Luz del Mundo exigen seguridad". El Informador (in Spanish). 18 February 2012. Retrieved 20 October 2012.

- References

- Ávila Meléndez, Luis Arturo (2008). "Entre las cosas de Dios y las preocupaciones terrenales: el camino contradictorio hacia la santidad en la "Iglesia de la Luz del Mundo"". In Zalpa, Hans Egil; Offerdal, Genaro. ¿El reino de Dios es en este mundo? El papel ambiguo de las religiones en la lucha contra la pobreza (PDF) (in Spanish). Bogotá, Colombia: CLACSO-Siglo del Hombre. ISBN 978-958-665-126-4. Retrieved 30 December 2012.

- Biglieri, Paula (2000). "Ciudadanos de La Luz. Una mirada sobre el auge de la Iglesia La Luz del Mundo". Estudios Sociológicos (in Spanish). El Colegio de México. XVIII (2): 403–428. ISSN 0185-4186. OCLC 47166994. Retrieved 25 December 2012.

- Bromley, David G.; Melton, J. Gordon (2002). Cults, religion, and violence. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-66898-9.

- Cobián R, Felipe (11 December 2005). "Responde La Luz del Mundo". Proceso (in Spanish). Retrieved 4 December 2012.

- De la Torre, Renee (2000). Los hijos de la luz: discurso, identidad y poder en La Luz del Mundo (in Spanish). ITESO. ISBN 968-5087-15-6. Retrieved 8 October 2013.

- Dormady, Jason H. (2011). Primitive Revolution: Restorationist Religion and the Idea of the Mexican Revolution 1940--1964. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 978-0-8263-4951-4.

- Fortuny, Patricia (2001). "Religión y figura femenina : entre la norma y la práctica" (PDF). Revista de Estudios de Género. La ventana (in Spanish). Universidad de Guadalajara. 2 (14). Retrieved 18 September 2012.

- Fortuny, Patricia (2002). "Chapter 2: The Santa Cena of the Luz del Mundo Church: A Case of Contemporary Transnationalism". In Ebaugh, Helen Rose; Saltzman Chafetz, Janet. Religion Across Borders: Transnational Immigrant Networks. Rowman Altamira. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-7591-0226-2. Retrieved 31 December 2012.

- Fortuny, Patrica (1995). "Origins, Development and Perspectives of La Luz del Mundo Church". Religion. 25 (2): 147–162. doi:10.1006/reli.1995.0014.

- Fortuny, Patricia; Williams, Philip J. (2008). "Iglesias y espacios públicos : Lugares de identidad de mexicanos en Metro Atlanta". Trayectorias (in Spanish). Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León. 10 (26): 7–19. ISSN 2007-1205. OCLC 44417986. Retrieved 5 November 2012.

- Garma Navarro, Carlos (2004). "The Legal Situation of Religious Minorities in Mexico: The Current situation, Problems, and Conflicts". In James T. Richardson. Regulating Religion: Case Studies from Around the Globe. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. ISBN 978-0-306-47886-4. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- González, Ondina E.; González, Justo L. (2008). Christianity in Latin America: A History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-86329-2.

- Greenway, Roger S. (1973). "The 'Luz Del Mundo' Movement in Mexico". Missiology: An International Review. 1 (2): 113–124. doi:10.1177/009182967300100211.

- Gill, Kenneth D. (1994). Toward a contextualized theology for the Third World : the emergence and development of Jesus' name pentecostalism in Mexico. Studies in the intercultural history of Christianity. 90. Peter Lang. p. 277. ISBN 978-3-631-47096-1.

- Joaquín Flores, Samuel (28 October 1997). "A la opinion publica". El Norte. Monterrey, Mexico.

- Joaquín, Benjamin (2004). El Elegido de Dios (in Spanish). Guadalajara: Fundación Maestro Samuel Joaquín Flores.

- Marquardt, Marie (2011). "4 Picking Up The Cross". Living "Illegal": The Human Face of Unauthorized Immigration. The New Press. p. 119. ISBN 978-1-59558-651-3. Retrieved 8 October 2013.

- Masferrer Kan, Elio (2004). ¿Es del César o es de Dios? Un modelo antropológico del campo religioso (in Spanish). Plaza y Valdés, CEIICH-UNAM. ISBN 978-970-722-316-5.

- Monsiváis, Carlos (2002). "¿Por qué estudiar al protestantismo mexicano?". Protestantismo, diversidad y tolerancia (PDF) (in Spanish). Comisión Nacional de los Derechos Humanos. ISBN 978-970-644-277-2.

- Nutini, Hugo G. (2000). "Native Evangelism in Central Mexico". Ethnology. University of Pittsburgh. 39 (1). doi:10.2307/3773794. ISSN 0014-1828. OCLC 1568323.

- Ochoa Bohórquez, Ana Victoria (2011). "Lo religioso como agente transformador de la cultura: Iglesia La Luz del Mundo: surgimiento, expansión, usos y ceremonias México-Colombia 1926–2006" (PDF) (in Spanish). Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Retrieved 4 September 2012.

- Wyatt, Timothy (2011). "Iglesia La Luz Del Mundo" (PDF). Houston History. University of Houston. 8 (3): 9. ISSN 2165-6614. OCLC 163568525. Retrieved 25 December 2012.

Further reading

Note: Most of De la Torre's work listed below was incorporated into her book Los hijos de La Luz.

- De la Peña, Guillermo; De la Torre, Renée (1990). "Religión y política en los barrios populares de Guadalajara". Estudios Sociológicos (in Spanish). El Colegio de México. 8 (24): 571–602. JSTOR 40420093. OCLC 85446277.

- De la Torre, Renée; Fortuny, Patricia (1991). "La construcción de una identidad nacional en La Luz del Mundo". Cristianismo y Sociedad (in Spanish). XXIX (109): 33–47. ISSN 0011-1457. OCLC 2259924.

- De la Torre, Renée (1993). Discurso, identidad y poder en la construcción de una identidad religiosa: la Luz del Mundo (Thesis) (in Spanish). ITESO. Retrieved 8 October 2013.

- De la Torre, Renée (1994). "Al que no habla Dios no lo oye. Al que Dios no oye, no habla. Orden social y discurso hegemónico en La Luz del Mundo". In Roth Senef, Andrew; Lameiras, José. El verbo oficial: política moderna en dos campos periféricos del estado mexicano (in Spanish). El Colegio de Michoacán, ITESO. pp. 147–179. ISBN 978-968-6959-07-9.

- De la Torre, Renée (1994). "Comunicación como acto creador de la identidad religiosa. Estudio de caso en La Luz del Mundo". Cuadernos del Departamento de Comunicación del ITESO (in Spanish). ITESO. 1: 9–31.

- De la Torre, Renée (1994–1995). "Guadalajara, la perla de la Luz del Mundo". Renglones (in Spanish). ITESO. 10 (30): 34–39. ISSN 0186-4963. OCLC 13536814.

- De la Torre, Renée (1996). "Pinceladas de una ilustración etnográfica: La Luz del Mundo en Guadalajara". In Giménez, Gilberto. Identidades Religiosas y Sociales en México (in Spanish). Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. ISBN 978-968-36-4956-0.

- De la Torre, Renée (1996). "Los motivos de la conversión: Estudio de caso en La Luz del Mundo, Guadalajara, México". Iztapalapa (in Spanish). Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana. 39: 109–126. ISSN 0185-4259. OCLC 6826600.

- De la Torre, Renée (2000). "Una Iglesia mexicana con proyección internacional: La Luz del Mundo". In Masferrer Kan, Elio. Sectas o iglesias: Viejas o nuevas religiones (in Spanish) (2nd ed.). Plaza y Valdés, Asociación Latinoamericana para el estudio de las Religiones. pp. 261–282. ISBN 978-968-856-579-7.

- Dormady, Jason H. (2007). "Not Just a Better Mexico": Intentional Religious Community and the Mexican State, 1940--1964. University of California, Santa Barbara: ProQuest. ISBN 978-0-549-15247-7.

- Fortuny, Patricia (1996). "La Luz del Mundo: una oferta múltiple de salvación". Estudios Jalisciences (in Spanish). El Colegio de Jalisco. 24. OCLC 25067830.

- Fortuny Loret de Mola, Patricia (1992). "La historia mítica del fundador de la lglesia La Luz del Mundo". In Castañeda, Carmen. Vivir en Guadalajara. La Ciudad y sus Funciones (in Spanish). Ayuntamiento de Guadalajara. pp. 363–379.

- Fortuny-Loret de Mola, Patricia (2012). "La Luz del Mundo Church". In Juergensmeyer, Mark; Roof, Wade Clark. Encyclopedia of global religion. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. pp. 683–686. ISBN 978-0-7619-2729-7.

- Fortuny-Loret de Mola, Patricia (2012). "Migrantes y peregrinos de La Luz del Mundo: religión popular y comunidad moral transnacional". Nueva Antropología: Revista de Ciencias Sociales (in Spanish). Nueva Antropología A.C. 25 (77): 179–200. ISSN 0185-0636. OCLC 262698382.

- Morán Quiroz, Luis Rodolfo (1990). Alternativa religiosa en Guadalajara: una aproximación al estudio de las iglesias evangélicas. Colección Estudios Latinoamericanos (in Spanish). 3. Guadalajara, Mexico: Universidad de Guadalajara. ISBN 978-968-895-220-7.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to La Luz del Mundo Church. |