List of town walls in England and Wales

This list of town walls in England and Wales describes the fortified walls built and maintained around these towns and cities from the 1st century AD onwards. The first town walls were built by the Romans, following their conquest of Britain in 43 AD. The Romans typically initially built walled forts, some of which were later converted into rectangular towns, protected by either wooden or stone walls and ditches. Many of these defences survived the fall of the Roman Empire in the 4th and 5th centuries, and were used in the unstable post-Roman period. The Anglo-Saxon kings undertook significant planned urban expansion in the 8th and 9th centuries, creating burhs, often protected with earth and wood ramparts. These burh walls sometimes utilised older Roman fortifications, and themselves frequently survived into the early medieval period.

The Norman invaders of the 11th century initially focused on building castles to control their new territories, rather than town walls to defend the urban centres, but by the 12th century many new town walls were built across England and Wales, typically in stone. Edward I conquered North Wales in the late 13th century and built a number of walled towns as part of a programme of English colonisation. By the late medieval period, town walls were increasingly less military in character and more closely associated with civic pride and urban governance: many grand gatehouses were built in the 14th and 15th centuries. The English Civil War in 1640s saw many town walls pressed back into service, with older medieval structures frequently reinforced with more modern earthwork bastions and sconces. By the 18th century, however, most town walls were falling into disrepair: typically they were sold off and demolished, or hidden behind newer buildings as towns and cities expanded.

In the 20th century there was a resurgence in historical and cultural interest in these defences. Those towns and cities that still had intact walls renovated them to form tourist attractions. Some of Edward I's town walls in North Wales were declared part of the internationally recognised UNESCO World Heritage Site. Urban redevelopment has frequently uncovered new remnants of the medieval walls, with archaeological work generating new insights into the Roman and Anglo-Saxon defences.

List

| Place | County | Date built | Condition | Image | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abergavenny | Gwent | Masonry fragments | A small Norman wall was built around the town in the 11th century, linked to Abergavenny Castle. The Norman wall was demolished in the 12th century and a new stone wall was built in the late 13th century, approximately 350 by 215 metres (1,100 ft × 710 ft). This was destroyed by the modern period.[1] | |||

| Alnwick | Northumberland | Two gatehouses survive |  |

The walls were built in the 15th century to protect Alnwick against border instability and raiding, and commemorated the powerful local Percy family, who controlled the local castle.[2][3] | ||

| Bath | Somerset | Fragmentary remains |  |

Bath's first walls were built by the Romans. The Anglo-Saxons established a fortified burh at Bath, utilising the existing walls, and they were further strengthened during the medieval period. Parts of one medieval gatehouse still survive.[4][5] | ||

| Beaumaris | Gwynedd | Vestiges |  |

The town was captured by Owain Glyndŵr in 1400. Once recaptured by English forces, a stone wall with three gates was built around the town, and maintained until the late 17th century.[6][7] | ||

| Berwick-on-Tweed | Northumberland | Substantially intact |  |

The first walls built in the early 14th century under Edward I were 2 mi (3.2 km) long. Replaced in 1560 by a set of Italian-inspired walls with 5 large stone bastions, the walls are today the best-preserved post-medieval town defences in England.[8] | ||

| Beverley | East Riding of Yorkshire | One gatehouse survives |  |

12th century Beverley was protected by a "great ditch" rather than a stone wall. In the early 15th century 3 brick gatehouses were built; more ditches and other fortifications were later added, but these failed to protect the town during the Civil War.[9][10] | ||

| Brecon | Powys | Vestiges |  |

Originally constructed by Humphrey de Bohun after 1240, the walls were built of stone, with 4 gatehouses and 10 semi-circular bastions. They were largely destroyed during the Civil War.[11][12] | ||

| Bridgnorth | Shropshire | Vestiges |  |

Bridgnorth's town walls were initially constructed in timber between 1216 and 1223; murage grants allowed them to be upgraded to stone between the 13th and 15th centuries including 5 gates.[13] | ||

| Bristol | Bristol | Fragmentary remains |  |

The fine St John's Gate is built into the church under its spire; the line of the walls is walkable.[14] | ||

| Caerleon | Gwent | Fragmentary remains |  |

[15] | ||

| Caernarfon | Gwynedd | 1283–92 | Largely intact |  |

Constructed by Edward I at a cost of £3,500, alongside the castle, the walls are 2,408 ft (734 m) long and include eight towers and two gatehouses. Today they form part of the UNESCO world heritage site administered by Cadw.[16][17] | |

| Caerwent | Gwent | Substantial remains |  |

[18] | ||

| Canterbury | Kent | 3rd-16th centuries | Substantial remains |  |

First built by the Romans in the 3rd century, retained by the Anglo-Saxons, the walls were rebuilt in the late 14th century owing to fears of a French invasion and feature early gunports. Over half of the original circuit, with 17 out of 24 towers, survives.[19] | |

| Cardiff | Glamorgan | 12th-15th centuries | Vestiges |  |

First recorded in 1111, the walls were 1.28 mi (2.06 km) long and 10 ft (3.0 m) high with 5 town gates. Sections collapsed in the 18th century, many stones being reused as building material. The last large section was demolished in 1901.[20] | |

| Carlisle | Cumbria | Substantial remains |  |

[21] | ||

| Castle Acre | Norfolk | Fragmentary remains |  |

[22] | ||

| Chepstow | Gwent | Substantial remains |  |

A late thirteenth century stone wall constructed for the twin purposes of defence and tax collection.[23] | ||

| Chester | Cheshire | 70 AD–12th century | Largely intact |  |

Chester's walls were originally built by the Romans between 70 and 80 AD and were used by the burh in 907. The Norman walls were extended to the west and the south to form a complete circuit, which now provides a walkway of about 2 mi (3.2 km).[24][25] | |

| Chichester | West Sussex | Substantial remains |  |

[26] | ||

| Cirencester | Gloucestershire | 3rd–4th century | Vestiges | Remnants of the stone walls of the Roman town of Corinium Dobunnorum are visible in the Abbey Grounds.[27] | ||

| Colchester | Essex | Substantial remains |  |

[28] | ||

| Conwy | Clwyd | Largely intact |  |

Constructed between 1283 and 1287 after the foundation of Conwy by Edward I, the walls are 0.8 mi (1.3 km) long, with 21 towers and 3 gatehouses, and formed an integrated system of defence alongside Conwy Castle.[29][30] | ||

| Coventry | West Midlands | 1350s–1534 | Fragmentary remains |  |

With its walls nearly 2.2 mi (3.5 km) around and 12 ft (3.7 m) high, with 32 towers and 12 gatehouses, repaired during the 1640s, Coventry was described as being the best-defended city in England outside London.[31][32] | |

| Cowbridge | Glamorgan | Substantial remains |  |

[33] | ||

| Cricklade | Wiltshire | Fragmentary remains | [34] | |||

| Denbigh | Clwyd | Substantial remains |  |

[35] | ||

| Durham | County Durham | Fragmentary remains | [36] | |||

| Exeter | Devon | Substantial remains |  |

[37] | ||

| Gloucester | Gloucestershire | Vestiges | [38] | |||

| Great Yarmouth | Norfolk | Substantial remains |  |

[39] | ||

| Hartlepool | County Durham | Substantial remains |  |

[40] | ||

| Hastings | East Sussex | Vestiges | [41] | |||

| Haverfordwest | Pembrokeshire | Vestiges | [42] | |||

| Hay-on-Wye | Powys | Vestiges | [43] | |||

| Hereford | Herefordshire | Fragmentary remains | .jpg) |

[44] | ||

| Ilchester | Somerset | Vestiges | [45] | |||

| Kidwelly | Carmarthenshire | Substantial remains |  |

[46] | ||

| Kings Lynn | Norfolk | Fragmentary remains |  |

[47] | ||

| Kingston upon Hull | East Riding of Yorkshire | 14th century | Vestiges |  |

Built of brick in the 14th century, with 4 main gates and up to 30 towers, the walls were maintained until the early 1700s. They were demolished during the building of the docks, beginning in the 1770s.[48] | |

| Langport | Somerset | Fragmentary remains |  |

[49] | ||

| Launceston | Cornwall | Substantial remains |  |

[50] | ||

| Lewes | East Sussex | Vestiges | [51] | |||

| Lincoln | Lincolnshire | Fragmentary remains |  |

[52] | ||

| London | London | Fragmentary remains |  |

Built by the Romans and maintained until the 18th century, nearly 3 mi (4.8 km) long, the wall defined the boundaries of the City of London with the Thames to the south. Short sections remain near the Tower of London and in the Barbican area.[53] | ||

| Ludlow | Shropshire | 1233–1317 | Fragmentary remains |  |

Built to defend this Welsh Marches market town, the walls remain in sections, as does the Broad Gate (shown in photo). The large Ludlow Castle is now a ruin but with substantial remains.[54] | |

| Malmesbury | Wiltshire | Vestiges | [55] | |||

| Monmouth | Gwent | 13th–15th century[56] | Only the Monnow Bridge gate survives |  |

Originally formed a circuit wall with four gatehouses, none of which survive. The fortified Monnow bridge still remains, the only surviving medieval bridge gate in the UK.[57] | |

| Newark on Trent | Nottinghamshire | Vestiges | [58] | |||

| Newcastle upon Tyne | Tyne and Wear | Substantial remains | Built during the 13th and 14th centuries the wall was about 2 mi (3.2 km) long, 6.5 ft (2.0 m) thick and 25 ft (7.6 m) high, with 6 main gates. The town was successfully defended twice; but during the Civil War the wall was breached using mines and artillery.[59] | |||

| Northampton | Northamptonshire | 11th–17th century | Destroyed by Royal order in 1662[60] | |||

| Norwich | Norfolk | Fragmentary remains |  |

|||

| Nottingham | Nottinghamshire | 1267-1334 | Vestiges | A fragment of the wall is visible in a hotel complex near Chapel Bar.[61] | ||

| Oxford | Oxfordshire | Fragmentary remains |  |

[62] | ||

| Pembroke | Pembrokeshire | Fragmentary remains | .jpg) |

A stretch of wall survives along Common Road, as well as the base of a tower, now surmounted by a 19th-century gazebo.[63] | ||

| Poole | Dorset | Vestiges | [64] | |||

| Portsmouth | Hampshire | 14th–18th century | Fragmentary remains | First constructed of earth and timber, probably in the late 14th century,[65] the walls were repeatedly repaired and rebuilt until the mid 18th century. They were largely removed in the 1870s and 80s.[65] | ||

| Richmond | North Yorkshire | Fragmentary remains |  |

[66] | ||

| Rochester | Kent | Fragmentary remains |  |

[67] | ||

| Rye, East Sussex | East Sussex | Substantial remains |  |

[68] | ||

| Salisbury | Wiltshire | 14/15th century | Fragments and one gatehuose | .jpg) |

North Gate. Two-storey building over and around north entrance to the Cathedral Close. | |

| Sandwich | Kent | Fragmentary remains |  |

[69] | ||

| Shrewsbury | Shropshire | 13th–14th century | Fragmentary remains |  |

Begun in the 13th century after attacks by the Welsh, adding to the natural defences of the Severn, the walls were strengthened by the Royalists during the Civil War. A tower and short sections remain, notably along the street named Town Walls.[70] | |

| Silchester | Hampshire | 3rd century | Substantial remains |  |

The Roman town of Calleva Atrebatum was abandoned around the 5th or 6th century. Much of the walls survive, the area within them largely farmland.[71] | |

| Southampton | Hampshire | Half the medieval circuit survives |  |

Built after French raids in 1338, the walls were 1.25 mi (2.01 km) long, with 29 towers and 8 gates. They were amongst the first in England to have new technology installed to existing fortifications, with new towers built specifically to house cannon.[72] | ||

| Stafford | Staffordshire | Vestiges |  |

|||

| Stamford | Lincolnshire | Fragmentary remains |  |

[73] | ||

| Swansea | Glamorgan | Vestiges |  |

[74] | ||

| Tenby | Pembrokeshire | Substantial remains |  |

[75] | ||

| Totnes | Devon | 14th century | Fragmentary remains |  |

Remains include the Baste Walls, South Street and the Eastgate, which was greatly altered in the 19th century.[76] | |

| Verulamium | Hertfordshire | 2nd-3rd century | Fragmentary remains | The site of the Roman town of Verulamium was abandoned when the later settlement of St. Albans was established nearby.[77] | ||

| Warkworth | Northumberland | Fragmentary remains |  |

[78] | ||

| Warwick | Warwickshire | Fragmentary remains |  |

[79] | ||

| Winchelsea | East Sussex | Substantial remains |  |

[80] | ||

| Winchester | Hampshire | Substantial remains |  |

[81] | ||

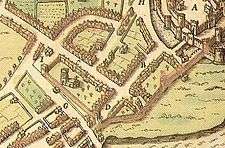

| Worcester | Worcestershire | 1st–12th century | Vestiges |  |

First built by the Romans, the walls were extended by the Anglo-Saxons to create a walled burh. A longer circuit of stone walls was built in the late 12th century and further fortified during the Civil War.[82][83] | |

| York | North Yorkshire | 3rd–14th century | Largely intact |  |

2.5 mi (4.0 km) long, enclosing an area of 263 acres,[84] the defences are the best preserved in England. On high ramparts, retaining all their main gateways,[85] the walls incorporate Roman, Norman and medieval work with modern renovations.[86] |

Notes

- ↑ The medieval reconstruction of the city walls is by Worcester City Museums, based on archaeological and historical data available in 2000.

References

- ↑ Creighton and Higham, pp.158-159, 273; Abergavenny Town Wall, Gatehouse website, accessed 10 October 2011; Coflein. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Pettifer (2002), p.172; Creighton and Higham, p.141.

- ↑ Historic England. "Monument No. 7110". PastScape. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Creighton and Higham, pp.36, 60, 254.

- ↑ Historic England. "Monument No. 204122". PastScape. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Taylor, pp.36-37.

- ↑ Coflein. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Mackenzie, p.440; Forster, pp.97-99; Creighton and Higham, pp.97, 270.

- ↑ Turner, p.99; Fortifications, A History of the County of York East Riding: Volume 6: The borough and liberties of Beverley (1989), pp. 178-180, accessed 13 October 2011.

- ↑ Historic England. "Monument No. 79096". PastScape. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Pettifer (2000), pp.8-9.

- ↑ Coflein. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Fragment of Town Walls (listed section), rear of 93 Cartway (E and N side), SMRNO00374, Discovering Shrophshire's History, accessed 22 October 2011; Bridgnorth Town Defences, Gatehouse website, accessed 22 October 2011; Historic England. "Monument No. 114682". PastScape. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Historic England. "Monument No. 1005392". PastScape. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Coflein. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Taylor, pp. 13, 41; Creighton and Higham, pp. 102, 273; Lilley, p. 106.

- ↑ Coflein. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Coflein. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Historic England. "Monument No. 464679". PastScape. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Coflein. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Historic England. "Monument No. 10650". PastScape. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Historic England. "Monument No. 1157103". PastScape. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Coflein. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Ward, pp.6, 31–33; Heritage Trails: Chester City Walls Trail, Cheshire West and Chester Council, accessed 23 September 2011.

- ↑ Historic England. "Monument No. 69073". PastScape. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Historic England. "Monument No. 924434". PastScape. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Historic England. "Monument No. 660823". PastScape. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Historic England. "Monument No. 383745". PastScape. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Creighton and Higham, p.223; Ashbee, pp.47, 55.

- ↑ Coflein. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Introduction: the building of the wall, Coventry's City Wall and Gates, retrieved 1 October 2008.

- ↑ Historic England. "Monument No. 869475". PastScape. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Coflein. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Historic England. "Monument No. 222196". PastScape. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Coflein. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Historic England. "Monument No. 24470". PastScape. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Historic England. "Monument No. 448309". PastScape. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Historic England. "Monument No. 115263". PastScape. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Historic England. "Monument No. 133974". PastScape. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Historic England. "Monument No. 27813". PastScape. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Historic England. "Monument No. 417248". PastScape. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Coflein. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Coflein. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Historic England. "Monument No. 110198". PastScape. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Historic England. "Monument No. 196504". PastScape. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Coflein. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Historic England. "Monument No. 879529". PastScape. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Historic England. "Monument No. 1062126". PastScape. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Historic England. "Monument No. 193689". PastScape. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Historic England. "Monument No. 437141". PastScape. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Historic England. "Monument No. 406490". PastScape. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Historic England. "Monument No. 326541". PastScape. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Historic England. "Monument No. 405081". PastScape. Retrieved 9 October 2011.; http://www.museumoflondon.org.uk/English/Collections/OnlineResources/Londinium/Today/vizrom/01+wall.htm. Retrieved 30 May 2010.

- ↑ Historic England. "Monument No. 111060". PastScape. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Historic England. "Monument No. 212606". PastScape. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Kissack, p.36; Creighton and Higham, p.95.

- ↑ Creighton and Higham, pp.48, 272; Coflein. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Historic England. "Monument No. 322371". PastScape. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Hearnshaw, (1924); Around the Town Walls, National Trail, accessed 25 September 2011; Historic England. "Newcastle town walls (1005274)". PastScape. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ A History of the County of Northampton: Volume 3. Retrieved July 2013

- ↑ Historic England. "Monument No. 317520". PastScape. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Historic England. "Monument No. 338452". PastScape. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Coflein. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Historic England. "Monument No. 458242". PastScape. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- 1 2 Patterson (1985).

- ↑ Historic England. "Monument No. 21636". PastScape. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Historic England. "Monument No. 416085". PastScape. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Historic England. "Monument No. 1395251". PastScape. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Historic England. "Monument No. 468369". PastScape. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Historic England. "Monument No. 68055". PastScape. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Historic England. "Monument No. 241057". PastScape. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- ↑ Creigham and Higham, pp.114, 257; Turner, pp.165-166; MSH60, Southampton HER, accessed 19 October 2011.

- ↑ Historic England. "Monument No. 347829". PastScape. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Coflein. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Coflein. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Historic England. "Monument No. 446486". PastScape. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Historic England. "Monument No. 361847". PastScape. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- ↑ Historic England. "Monument No. 7904". PastScape. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Historic England. "Monument No. 333662". PastScape. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Historic England. "Monument No. 978700". PastScape. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Historic England. "Monument No. 231024". PastScape. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Baker and Holt, p.147; Baker, Dalwood, Holt, Mundy and Taylor, p.73; Bradley and Gaimster, p.274; Harrington, p.28

- ↑ Historic England. "Monument No. 116137". PastScape. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Wilson and Mee (2005), p.1

- ↑ Wilson and Mee (2005), p.ix.

- ↑ Pevsner and Neave (1995), p.192

Bibliography

- Baker, Nigel and Richard Holt. (2004) Urban Growth and the Medieval Church: Gloucester and Worcester. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate. ISBN 978-0-7546-0266-8.

- Baker, Nigel, Hal Dalwood, Richard Holt, Charles Mundy and Gary Taylor. (1992) "From Roman to medieval Worcester: development and planning in the Anglo-Saxon city," Antiquity Vol. 66, pp. 65–74.

- Bradley, John and Märit Gaimster. (2004) (eds) "Medieval Britain and Ireland in 2003," Medieval Archaeology Vol. 48 pp. 229–350.

- Clarke, Stephen and Jane Bray. (2003) "The Norman town defences of Abergavenny," Medieval Archaeology Vol. 27, pp. 186–189.

- Creighton, Oliver Hamilton and Robert Higham. (2005) Medieval Town Walls: an Archaeology and Social History of Urban Defence. Stroud, UK: Tempus. ISBN 978-0-7524-1445-4.

- Forster, R. H. (1907) "The Walls of Berwick-upon-Tweed," Journal of the British Archaeological Association, Vol. 13, pp. 89–104.

- Hearnshaw, F. J. C. (1924) Newcastle-upon-Tyne. London: Sheldon Press. OCLC 609308241

- Kissack, Keith. (1974) Mediaeval Monmouth. Monmouth: Monmouth Historical and Educational Trust.

- Lilley, Keith D. (2010) "The Landscapes of Edward's New Towns: Their Planning and Design," in Williams and Kenyon (eds) (2010).

- Mackenzie, James D. (1896) The Castles of England: Their Story and Structure, Vol II. New York: Macmillan. OCLC 504892038.

- Patterson, B. H. (1985) A Military Heritage A history of Portsmouth and Portsea Town Fortifications. Fort Cumberland & Portsmouth Militaria Society.

- Pettifer, Adrian. (2000) Welsh Castles: a Guide by Counties. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0-85115-778-8.

- Pettifer, Adrian. (2002) English Castles: a Guide by Counties. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0-85115-782-5.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus and David Neave. (1995) Yorkshire: York and the East Riding, 2nd ed. London: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-071061-2

- Taylor, Arnold. (2008) Caernarfon Castle and Town Walls. Cardiff: Cadw. ISBN 978-1-85760-209-8.

- Turner, Hilary. (1971) Town Defences in England and Wales. London: John Baker. OCLC 463160092

- Ward, Simon. (2009) Chester: A History. Chichester, UK: Phillimore. ISBN 978-1-86077-499-7.

- Williams, Diane M. and John R. Kenyon. (eds) (2010) The Impact of the Edwardian Castles in Wales. Oxford: Oxbow Books. ISBN 978-1-84217-380-0.

- Wilson, Barbara and Frances Mee. (2005) The City Walls and Castles of York: The Pictorial Evidence, York Archaeological Trust. ISBN 978-1-874454-36-6.