Nanofluidics

Nanofluidics is the study of the behavior, manipulation, and control of fluids that are confined to structures of nanometer (typically 1–100 nm) characteristic dimensions (1 nm = 10−9 m). Fluids confined in these structures exhibit physical behaviors not observed in larger structures, such as those of micrometer dimensions and above, because the characteristic physical scaling lengths of the fluid, (e.g. Debye length, hydrodynamic radius) very closely coincide with the dimensions of the nanostructure itself.

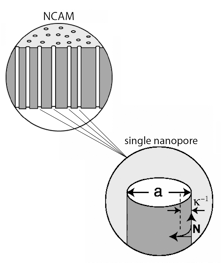

When structures approach the size regime corresponding to molecular scaling lengths, new physical constraints are placed on the behavior of the fluid. For example, these physical constraints induce regions of the fluid to exhibit new properties not observed in bulk, e.g. vastly increased viscosity near the pore wall; they may effect changes in thermodynamic properties and may also alter the chemical reactivity of species at the fluid-solid interface. A particularly relevant and useful example is displayed by electrolyte solutions confined in nanopores that contain surface charges, i.e. at electrified interfaces, as shown in the nanocapillary array membrane (NCAM) in the accompanying figure.

All electrified interfaces induce an organized charge distribution near the surface known as the electrical double layer. In pores of nanometer dimensions the electrical double layer may completely span the width of the nanopore, resulting in dramatic changes in the composition of the fluid and the related properties of fluid motion in the structure. For example, the drastically enhanced surface-to-volume ratio of the pore results in a preponderance of counter-ions (i.e. ions charged oppositely to the static wall charges) over co-ions (possessing the same sign as the wall charges), in many cases to the near-complete exclusion of co-ions, such that only one ionic species exists in the pore. This can be used for manipulation of species with selective polarity along the pore length to achieve unusual fluidic manipulation schemes not possible in micrometer and larger structures.

Theory

In 1965, Rice and Whitehead published the seminal contribution to the theory of the transport of electrolyte solutions in long (ideally infinite) nanometer-diameter capillaries.[1] Briefly, the potential, ϕ, at a radial distance, r, is given by the Poisson-Boltzmann equation,

where κ is the inverse Debye length,

determined by the ion number density, n, the dielectric constant, ε, the Boltzmann constant, k, and the temperature, T. Knowing the potential, φ(r), the charge density can then be recovered from the Poisson equation, whose solution may be expressed as a modified Bessel function of the first kind, I0, and scaled to the capillary radius, a. An equation of motion under combined pressure and electrically-driven flow can then be written,

where η is the viscosity, dp/dz is the pressure gradient, and Fz is the body force driven by the action of the applied electric field, Ez, on the net charge density in the double layer. When there is no applied pressure, the radial distribution of the velocity is given by,

From the equation above, it follows that fluid flow in nanocapillaries is governed by the κa product, that is, the relative sizes of the Debye length and the pore radius. By adjusting these two parameters and the surface charge density of the nanopores, fluid flow can be manipulated as desired.

Fabrication

Nanostructures can be fabricated as single cylindrical channels, nanoslits, or nanochannel arrays from materials such as silicon, glass, polymers (e.g. PMMA, PDMS, PCTE) and synthetic vesicles.[2] Standard photolithography, bulk or surface micromachining, replication techniques (embossing, printing, casting and injection molding), and nuclear track or chemical etching,[3][4] are commonly used to fabricate structures which exhibit characteristic nanofluidic behavior.

Applications

Because of the small size of the fluidic conduits, nanofluidic structures are naturally applied in situations demanding that samples be handled in exceedingly small quantities, including Coulter counting,[5] analytical separations and determinations of biomolecules, such as proteins and DNA,[6] and facile handling of mass-limited samples. One of the more promising areas of nanofluidics is its potential for integration into microfluidic systems, i.e. micrototal analytical systems or lab-on-a-chip structures. For instance, NCAMs, when incorporated into microfluidic devices, can reproducibly perform digital switching, allowing transfer of fluid from one microfluidic channel to another,[7][8] selectivity separate and transfer analytes by size and mass,[7][9][10][11][12] mix reactants efficiently,[13] and separate fluids with disparate characteristics.[7][14] In addition, there is a natural analogy between the fluid handling capabilities of nanofluidic structures and the ability of electronic components to control the flow of electrons and holes. This analogy has been used to realize active electronic functions such as rectification[15][16] and field-effect[17][18][19] and bipolar transistor[20][21] action with ionic currents. Application of nanofluidics is also to nano-optics for producing tuneable microlens array[22][23]

Nanofluidics have had a significant impact in biotechnology, medicine and clinical diagnostics with the development of lab-on-a-chip devices for PCR and related techniques.[24]

Because the science of nanofluidics is still in its infancy, we can expect rapid development of new applications in the coming years.

Challenges

There are a variety of challenges associated with the flow of liquids through carbon nanotubes and nanopipes. A common occurrence is channel blocking due to large macromolecules in the liquid. Also, any insoluble debris in the liquid can easily clog the tube. A solution for this researchers are hoping to find is a low friction coating or channel materials that help reduce the blocking of the tubes. Also, due to the large size of polymers, including biologically relevant molecules such as DNA often fold in vivo. This causes blockage because typical DNA molecules from a virus have lengths of approx. 100–200 kilobases and will form a random coil of the radius some 700 nm in aqueous solution at 20%. This is also several times greater than the pore diameter of even large carbon pipes and two orders of magnitude the diameter of a single walled carbon nanotube.

See also

References

- ↑ Rice, C. L.; Whitehead, R. (1965). "Electrokinetic Flow in a Narrow Cylindrical Capillary". Journal of Physical Chemistry. 69 (11): 4017–4024. doi:10.1021/j100895a062.

- ↑ Karlsson, M.; Davidson, M.; Karlsson, R.; Karlsson, A.; Bergenholtz, J.; Konkoli, Z.; Jesorka, A.; Lobovkina, T.; Hurtig, J.; Voinova, M.; Orwar, O. (2004). "Biomimetic nanoscale reactors and networks". Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 55: 613–649. doi:10.1146/annurev.physchem.55.091602.094319. PMID 15117264.

- ↑ Lichtenberg, J.; Baltes, H. (2004). Advanced Micro & Nanosystems. 1. pp. 319–355. ISBN 3-527-30746-X.

- ↑ Mijatovic, D.; Eijkel, J. C. T.; van den Berg, A (2005). "Technologies for nanofluidic systems: Top-down vs. Bottom-up—a review". Lab on a Chip. 5 (5): 492–500. doi:10.1039/b416951d. PMID 15856084.

- ↑ Saleh, O. A.; Sohn, L. L (2001). "Quantitative sensing of nanoscale colloids using a microchip Coulter counter". Review of Scientific Instruments. 72 (12): 4449–4451. doi:10.1063/1.1419224.

- ↑ Han, C.; Jonas, O. T.; Robert, H. A.; Stephen, Y. C (2002). "Gradient nanostructures for interfacing microfluidics and nanofluidics". Applied Physics Letters. 81 (16): 3058–3060. doi:10.1063/1.1515115.

- 1 2 3 Cannon, J. D.; Kuo, T.-C.; Bohn, P. W.; Sweedler, J. V (2003). "Nanocapillary array interconnects for gated analyte injections and electrophoretic separations in multilayer microfluidic architectures". Analytical Chemistry. 75 (10): 2224–2230. doi:10.1021/ac020629f. PMID 12918959.

- ↑ Pardon G, Gatty HK, Stemme G, van der Wijngaart W, Roxhed N (2012). "Pt-Al2O3 dual layer atomic layer deposition coating in high aspect ratio nanopores". Nanotechnology. 24 (1): 015602. doi:10.1088/0957-4484/24/1/015602. PMID 23221022.

- ↑ Ramirez, P.; Mafe, S.; Alcaraz, A.; Cervera, J (2003). "Modeling of pH-Switchable Ion Transport and Selectivity in Nanopore Membranes with Fixed Charges". Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 107 (47): 13178–13187. doi:10.1021/jp035778w.

- ↑ Kohli, P.; Harrell, C. C.; Cao, Z.; Gasparac, R.; Tan, W.; Martin, C. R (2004). "DNA-functionalized nanotube membranes with single-base mismatch selectivity". Science. 305 (5686): 984–986. doi:10.1126/science.1100024. PMID 15310896.

- ↑ Jirage, K. B.; Hulteen, J. C.; Martin, C. R (1999). "Effect of thiol chemisorption on the transport properties of gold nanotubule membranes". Analytical Chemistry. 71 (21): 4913–4918. doi:10.1021/ac990615i. PMID 21662836.

- ↑ Kuo, T. C.; Sloan, L. A.; Sweedler, J. V.; Bohn, P. W (2001). "Manipulating Molecular Transport through Nanoporous Membranes by Control of Electrokinetic Flow: Effect of Surface Charge Density and Debye Length". Langmuir. 17 (20): 6298–6303. doi:10.1021/la010429j.

- ↑ Tzu-C. Kuo, Kim, H.K.; Cannon, D.M. Jr.; Shannon, M.A.; Sweedler, J.V.; Bohn, P.W (2004). "Nanocapillary Arrays Effect Mixing and Reaction in Multilayer Fluidic Structures". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 43 (14): 1862–1865. doi:10.1002/anie.200353279.

- ↑ Fa, K.; Tulock, J. J.; Sweedler, J. V.; Bohn, P. W (2005). "Profiling pH gradients across nanocapillary array membranes connecting microfluidic channels". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 127 (40): 13928–13933. doi:10.1021/ja052708p. PMID 16201814.

- ↑ Cervera, J.; Schiedt, B.; Neumann, R.; Mafe, S.; Ramirez, P., Ionic conduction, rectification, and selectivity in single conical nanopores (2006). "Ionic conduction, rectification, and selectivity in single conical nanopores". Journal of Chemical Physics. 124 (10): 104706. doi:10.1063/1.2179797. PMID 16542096.

- ↑ Guan, W.; Fan, R.; Reed, M. (2011). "Field-effect reconfigurable nanofluidic ionic diodes". Nature Communications. 2: 506. doi:10.1038/ncomms1514. PMID 22009038.

- ↑ Karnik, R.; Castelino, K.; Majumdar, A., Field-effect control of protein transport in a nanofluidic transistor circuit (2006). "Field-effect control of protein transport in a nanofluidic transistor circuit". Applied Physics Letters. 88 (12): 123114. doi:10.1063/1.2186967.

- ↑ Karnik, R.; Fan, R.; Yue, M.; Li, D.Y.; Yang, P.D.; Majumdar, A. (2005). "Electrostatic control of ions and molecules in nanofluidic transistors". NanoLetters. 5 (5): 943–948. doi:10.1021/nl050493b.

- ↑ Pardon G, van der Wijngaart W (2013). "Modeling and simulation of electrostatically gated nanochannels". Advances in Colloid and Interface Science. 199–200: 78–94. doi:10.1016/j.cis.2013.06.006. PMID 23915526.

- ↑ Daiguji, H.; Yang, P.D.; Majumdar, A. (2004). "Ion transport in nanofluidic channels". NanoLetters. 4: 137–142. doi:10.1021/nl0348185.

- ↑ Vlassiouk, Ivan & Siwy, Zuzanna S. (2007). "Nanofluidic Diode". Nano Letters. 7 (3): 552–556. doi:10.1021/nl062924b. PMID 17311462.

- ↑ Grilli, S.; Miccio, L.; Vespini, V.; Finizio, A.; De Nicola, S.; Ferraro, Pietro (2008). "Liquid micro-lens array activated by selective electrowetting on lithium niobate substrates". Optics Express. 16 (11): 8084–8093. doi:10.1364/OE.16.008084. PMID 18545521.

- ↑ Ferraro, P. (2008). "Manipulating Thin Liquid Films for Tunable Microlens Arrays". Optics & Photonics News. 19: 34–34. doi:10.1364/opn.19.12.000034.

- ↑ Herold, KE; Rasooly, A, eds. (2009). Lab-on-a-Chip Technology: Biomolecular Separation and Analysis. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-47-9.