New Mexico State Penitentiary riot

| New Mexico State Penitentiary riot | |

|---|---|

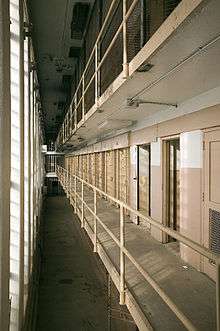

One side of cellblock 4, where isolated prisoners were held | |

| Location | Santa Fe County, New Mexico |

| Date | February 2–3, 1980 (MDT) |

Attack type | Rioting, hostage-taking |

| Deaths | 33 |

Non-fatal injuries | 200+ |

| Perpetrators | Inmates |

The New Mexico State Penitentiary riot, which took place on February 2 and 3, 1980, in the state's maximum security prison south of Santa Fe, was one of the most violent prison riots in the history of the American correctional system: 33 inmates died and more than 200 inmates were treated for injuries.[1] None of the 12 officers taken hostage were killed, but seven were treated for injuries caused by beatings and rapes.[2] This was the third major riot at the NM State Penitentiary, the first occurring on 19 July 1922[3] and the second on 15 June 1953.[4]

Author Roger Morris suggests the death toll may have been higher, as a number of bodies were incinerated or dismembered during the course of the mayhem.[5]

Causes

The causes of the New Mexico Penitentiary riot are well documented. Author R. Morris wrote that "the riot was a predictable incident based on an assessment of prison conditions".[1] Prison overcrowding and inferior prison services, common problems in many correctional facilities, were major causes of the disturbance.[1] On the night of the riot, there were 1,136 inmates in a prison designed for only 900.[6] Prisoners were not adequately separated. Many were housed in communal dormitories that were unsanitary and served poor-quality food.

|

Another major cause of the riot was the cancellation of educational, recreational and other rehabilitative programs that had run from 1970 to 1975. In that five-year period, the prison had been described as relatively calm.[11] When the educational and recreational programs were stopped in 1975, prisoners had to be locked down for long periods. These conditions created strong feelings of deprivation and discontent in the inmate population that would later lead to violence and disorder.[12]

Inconsistent policies and poor communications meant relations between officers and inmates were always in decline. These patterns have been described as paralleling trends in other U.S. prisons from the 1960s and 1970s, and as a factor that moved inmates away from solidarity in the 1960s to violence and fragmentation in the 1970s.[11]

Following a change in prison leadership in the mid-1970s, the prison experienced a shortage of trained correctional staff. A subsequent investigation by the state attorney general's office found that prison officials began coercing prisoners to become informants in a strategy known as "the snitch game". The state's report said that retribution for snitching led to an increased incidence of violence at the prison in the late 1970s.[13]

Hostages taken

In the early morning of Saturday, February 2, 1980, two prisoners in south-side Dormitory E-2 overpowered an officer who had caught them drinking homemade liquor. Within minutes, four more of the 15 officers in the dormitory were also taken hostage. At this point the riot might have been contained; however, a fleeing officer left a set of keys behind.

Soon, E-2 dormitory was in the inmates' control. Prisoners using the captured keys now seized more officers as hostages, before releasing other inmates from their cells. Eventually, they were able to break into the prison's master-control center, giving them access to lock and door controls, weapons, and more key sets.

Violence ensues

By mid-morning events had spiraled out of control within the cellblocks. Murder and violence had erupted. Gangs were fighting gangs, and a group of rioters led by some of the most dangerous inmates (who by now had been released from solitary confinement) decided to break into cell block 4, which housed the protective-custody unit. This held the snitches and those labeled as informers. But it also housed inmates who were vulnerable, mentally ill or convicted of sex crimes. Initially, the plan was to take revenge on the snitches, but the violence soon became indiscriminate.

When the group reached cellblock 4, they found that they did not have keys to enter these cells. In response the rioters found blowtorches that had been brought into the prison as part of an ongoing construction project. They used these to cut through the bars over the next five hours. Locked in their cells, the segregated prisoners called to the State Police pleading for them to save them, but to no avail. Waiting officers did nothing despite there being a back door to cellblock 4, which would have offered a way to free them.[1]The inmates were not freed because State Police agreed to not enter the prison as long as officers held hostage were kept alive.

Meanwhile, the rioters began taunting prison officials over the radio about what they were going to do to the men in cell block 4. But no action was taken. One official was heard to remark about the men in the segregation facility, "it's their ass".[1] As dawn broke, an 'execution squad' finally cut through the grille and entered the cells. The security panel controlling the cell doors was burned off. Victims were pulled from their cells to be tortured, dismembered, decapitated, hanged, or burned alive.

During an edition of BBC's Timewatch program, an eyewitness described the carnage in cell block 4. They saw an inmate held up in front of a window; he was being tortured by using a blow torch on his face. They then started using the torch on his eyes, and then the inmate's head exploded. Another described the scene when he came across Mario Urioste, originally jailed for shoplifting, but was incarcerated in cell block 4 for his own protection after he had been apparently gang-raped by other inmates. Urioste was found hanged with his throat cut, and his dismembered genitals stuffed into his mouth.[14]

Men were killed with piping, work tools and knives. One man was partially decapitated after being thrown over the second tier balcony with a noose around his neck. The corpse was then dragged down and hacked up.[1] Fires had also begun raging unchecked throughout several parts of the prison.

Negotiations begin

Talks to end the riot stalled throughout the first 24 hours. This was because neither the inmates nor the state had a single spokesperson. Eventually, inmates made 11 general demands concerned with basic prison conditions like overcrowding, inmate discipline, educational services and improving food. The prisoners also demanded to talk to independent federal officials and members of the news media.

The officers who were held hostage were released after inmates met reporters. Some of the officers had been protected by inmates, but others had been brutally beaten and raped. Seven officers suffered severe injuries. "One was tied to a chair. Another lay naked on a stretcher, blood pouring from a head wound."[15]

Negotiations broke off again in the early hours of Sunday morning with state officials insisting no concessions had been made.

Inmates flee

However, eighty prisoners, wanting no further part in the disturbances, fled to the baseball field seeking refuge at the fence where the National Guard had assembled. On Sunday morning, more inmates began to trickle out of the prison seeking refuge. Black inmates led the exodus from the smoldering cellblocks.[1] These groups, large enough to defend themselves from other inmates, huddled together as smoke from the burned-out prison continued to drift across the recreation yard.

Order restored

By mid-afternoon, 36 hours after the riot had begun, heavily armed State Police officers accompanied by Santa Fe Police Department Officers entered the charred remains of the prison.

Official sources state that at least 33 inmates died. Some overdosed on drugs, but most were brutally murdered.[6] Twenty-three of the victims had been housed in the protective-custody unit. More than 200 inmates were treated for injuries sustained during the riot.[16] After the surrender, it took days before order was maintained enough to ensure that inmates could occupy the prison. Over the next two nights, National Guardsman threw lumber scraps from Santa Fe Lumber yards over the two-layered fence into the prison yard to ensure inmates who escaped into the yard would not freeze in the near-zero temperatures. Nevertheless, rape, gang fights, and racial conflict continued to break out among the inmates.[1]

Deaths

The official death toll included 33 people. Of them, 24 were Hispanic, 7 were White, one was Black, and one was Native American.[17]

Legacy

A few inmates were prosecuted for crimes committed during the uprising, but according to author Roger Morris, most crimes went unpunished. The longest additional sentence given to any convict was nine years. Nationally known criminal defense lawyer William L. Summers led the defense team in defending dozens of inmates charged in the riot's aftermath. In 1982, Mr. Summers received the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers Robert C. Heeney award, the highest award available to a criminal defense lawyer, for his work in defending the inmates prosecuted with regard to the riot.

After the riots, Governor King's administration resisted attempts to reform the prison.[1] Actions were not settled until the administration of Governor Toney Anaya seven years later. Much of the evidence was lost or destroyed during and after the riot. One federal lawsuit that had been filed by an inmate was held up in the New Mexico prison system for almost two decades. However, systemic reforms after the riot were undertaken following the Duran v. King consent decree, which included implementation of the Bureau Classification System under Cabinet Secretary Joe Williams. This reform work has developed the modern correctional system in New Mexico. Situated within 20 ft of the main control center, the prison library and its law collection remained relatively untouched.[18]

In 1989, the Bay Area Thrash band Exodus memorialized the riot in The Last Act of Defiance, the lead-off track of the album Fabulous Disaster.

The 2001 documentary Behind Bars: Riot in New Mexico covers the incident.[19]

By 2013 the state began conducting tours of the old prison.[20]

See also

- New Mexico Corrections Department

- List of law enforcement agencies in New Mexico

- List of United States state correction agencies

- List of U.S. state prisons

- Prison

References

- Morris, Roger (1983). The Devil's Butcher Shop: The New Mexico Prison Uprising. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 0826310621.

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 R. Morris, Devil's Butcher Shop: The New Mexico Prison Uprising, University of New Mexico Press, 1983.

- ↑ Mark Colvin The Penitentiary in Crisis: From Accommodation to Riot in New Mexico, SUNY Press (1992).

- ↑ Johnson, Judith R. (1994) "A Mighty Fortress is the Pen: Development of the New Mexico Penitentiary" pp. 119–132 In DeMark, Judith Boycw (editor) (1994) Essays in Twentieth-Century New Mexico History University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, New Mexico, ISBN 0-8263-1359-0, page 124

- ↑ Johnson, Judith R. (1994) "A Mighty Fortress is the Pen: Development of the New Mexico Penitentiary" pp. 119–132 In DeMark, Judith Boycw (editor) (1994) Essays in Twentieth-Century New Mexico History University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, New Mexico, ISBN 0-8263-1359-0, page 128

- ↑ Morris, Roger (1983). The Devil's Butcher Shop: The New Mexico Prison Uprising. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. page number needed

- 1 2 Schmalleger, Frank and Smikla, John Ortiz (2001) Corrections in the 21st Century McGraw Hill, New York, page 317, ISBN 978-0-02-802567-4

- ↑ "Report of the Attorney General on the February 2 and 3, 1980 Riot at the Penitentiary of New Mexico PART I The Penitentiary The Riot The Aftermath." (Archive) Attorney General of New Mexico. June 1980. p. J-1 (129/150). Retrieved on December 4, 2013.

- ↑ "Report of the Attorney General on the February 2 and 3, 1980 Riot at the Penitentiary of New Mexico PART I The Penitentiary The Riot The Aftermath." (Archive) Attorney General of New Mexico. June 1980. p. J-2 (130/150). Retrieved on December 4, 2013.

- ↑ "Report of the Attorney General on the February 2 and 3, 1980 Riot at the Penitentiary of New Mexico PART I The Penitentiary The Riot The Aftermath." (Archive) Attorney General of New Mexico. June 1980. p. J-3 (131/150). Retrieved on December 4, 2013.

- ↑ "Report of the Attorney General on the February 2 and 3, 1980 Riot at the Penitentiary of New Mexico PART I The Penitentiary The Riot The Aftermath." (Archive) Attorney General of New Mexico. June 1980. p. J-4 (132/150). Retrieved on December 4, 2013.

- 1 2 Mark Colvin, "The 1980 New Mexico Prison Riot", Social Problems, Vol. 29, No. 5, pp. 449–463, June 1982.

- ↑ B. Useem, "Disorganization and the New Mexico Prison Riot of 1980", American Sociological Review, Vol. 50, No. 5, pp. 677-688, October 1985.

- ↑ Feather, Bill (September 25, 1980). "'Snitching' system stirred prison riot". The Free Lance–Star. Retrieved March 21, 2015.

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3M-hPpuAqwQ

- ↑ Journal reporter http://www.abqjournal.com/2000/nm/future/9fut09-19-99.htm

- ↑ Rolland, Mike (1997) Descent into Madness: An inmate’s experience of the New Mexico State Prison riot Anderson Publishing, Cincinnati, Ohio, page number ? ISBN 978-0-87084-748-6

- ↑ Morris, p. 108.

- ↑ Rhea Joyce Rubin and Daniel S. Suvak, Libraries Inside: A Practical Guide for Prison Librarians, (McFarland & Co., 1995), p.195.

- ↑ "Behind Bars: Riot in New Mexico." (Archive) Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved on December 6, 2013.

- ↑ Santos, Fernanda. "For Riot Site in New Mexico, a Gift Shop but No Ghost Stories." (Print title: "For Riot Site, a Gift Shop but No Ghost Stories") The New York Times. November 9, 2013. Print date: November 10, 2013. p. A22. Retrieved on December 6, 2013.

Further reading

- Clifford, Frank. "Death threats may curb prison riot probe in U.S." Dallas Times Herald at The Montreal Gazette. Wednesday April 23, 1980. p. 96. Google News 96/112.

- Colvin, Mark (University of Colorado). "THE 1980 NEW MEXICO PRISON RIOT." (Archive) Social Problems. June 1982. Volume 29, No. 5.

- Colvin, Mark. "DESCENT INTO MADNESS: The New Mexico State Prison Riot." (Archive) p. 194-208.

- Dinitz, S. Barbarism in the New Mexico State Prison Riot: The Search for Meaning a Decade Later. NCJ 126260. In: Kelly, Robert J. and Donal E. MacNamara. Perspectives on Deviance: Dominance, Degradation and Denigration. p. 153-161. NCJ-126249. - National Criminal Justice Reference Service Page (Archive)

- Stone, W. G.; Hirliman, G. (1982). The Hate Factory. Random House. ISBN 978-0-440-03686-9.

- Holmes, Sue Major. "N.M. Prison's 1980 Riot Still Haunts 25 Years Later." Associated Press at the Albuquerque Journal. Wednesday, February 2, 2005.

- "Riot survivors tour old Santa Fe Penitentiary." (Archive) KOAT-TV. October 25, 2013.

- Krueger, Joline Gutierrez. "After 30 years, officers still haunted by New Mexico riot." The Albuquerque Journal.

- "Nation: What Happened to Our Men?" TIME. Monday February 18, 1980.

- "The New Mexico Prison Riot Answers to Your Questions By Professor Colvin." (Archive)

- Useem, Bert (University of Illinois at Chicago). "Disorganization and the New Mexico Prison Riot of 1980" (Archive). American Sociological Review, Vol. 50, No. 5 (Oct., 1985), pp. 677-688. Available at JSTOR.

External links

- "Report of the Attorney General on the February 2 and 3, 1980 Riot at the Penitentiary of New Mexico PART I The Penitentiary The Riot The Aftermath." (Archive) Attorney General of New Mexico. June 1980.

- "SENATE MEMORIAL 63 51st legislature - STATE OF NEW MEXICO - second session, 2014 INTRODUCED BY Lisa A. Torraco" (Archive). Government of New Mexico.

Coordinates: 35°33′52.85″N 106°3′38.60″W / 35.5646806°N 106.0607222°W