Ninurta

| Part of a series on |

| Ancient Mesopotamian religion |

|---|

|

|

Demigods and heroes |

| Related topics |

Ninurta was a Sumerian and the Akkadian god of hunting and war. He was worshipped in Babylonia and Assyria and in Lagash he was identified with the city god Ningirsu. In older transliteration the name is rendered Ninib and Ninip, and in early commentary he was sometimes portrayed as a solar deity.

A number of scholars have suggested that either the god Ninurta or the Assyrian king bearing his name (Tukulti-Ninurta I) was the inspiration for the Biblical character Nimrod.[1]

In Nippur, Ninurta was worshiped as part of a triad of deities including his father, Enlil and his mother, Ninlil. In variant mythology, his mother is said to be the harvest goddess Ninhursag. The consort of Ninurta was Ugallu in Nippur and Bau when he was called Ningirsu.

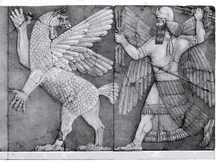

Ninurta often appears holding a bow and arrow, a sickle sword, or a mace named Sharur: Sharur is capable of speech in the Sumerian legend "Deeds and Exploits of Ninurta" and can take the form of a winged lion and may represent an archetype for the later Shedu.

In another legend, Ninurta battles a birdlike monster called Imdugud (Akkadian: Anzû); a Babylonian version relates how the monster Anzû steals the Tablets of Destiny from Enlil. The Tablets of Destiny were believed to contain the details of fate and the future.

Ninurta slays each of the monsters later known as the "Slain Heroes" (the Warrior Dragon, the Palm Tree King, Lord Saman-ana, the Bison-beast, the Mermaid, the Seven-headed Snake, the Six-headed Wild Ram), and despoils them of valuable items such as Gypsum, Strong Copper, and the Magilum boat.[2] Eventually, Anzû is killed by Ninurta who delivers the Tablet of Destiny to his father, Enlil.

There are many parallels with both and the story of Marduk (son of Enki) who slew Tiamat and delivered the Tablets of Destiny from Kingu to his father, Enki.

Cults

The cult of Ninurta can be traced back to the oldest period of Sumerian history. In the inscriptions found at Lagash he appears under his name Ningirsu, "the lord of Girsu", Girsu being the name of a city where he was considered the patron deity.

Ninurta appears in a double capacity in the epithets bestowed on him, and in the hymns and incantations addressed to him. On the one hand he is a farmer and a healing god who releases humans from sickness and the power of demons; on the other he is the god of the South Wind as the son of Enlil, displacing his mother Ninlil who was earlier held to be the goddess of the South Wind. Enlil's brother, Enki, was portrayed as Ninurta's mentor from whom Ninurta was entrusted several powerful Mes, including the Deluge.

He remained popular under the Assyrians: two kings of Assyria bore the name Tukulti-Ninurta. Ashurnasirpal II (883—859 BCE) built him a temple in the then capital city of Kalhu (the Biblical Calah, now Nimrud). In Assyria, Ninurta was worshipped alongside the gods Aššur and Mulissu.

In the late neo-Babylonian and early Persian period, syncretism seems to have fused Ninurta's character with that of Nergal. The two gods were often invoked together, and spoken of as if they were one divinity.

In the astral-theological system Ninurta was associated with the planet Saturn, or perhaps as offspring or an aspect of Saturn. In his capacity as a farmer-god, there are similarities between Ninurta and the Greek Titan Kronos, whom the Romans in turn identified with their Titan Saturn.

Family Tree

| An | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ninḫursaḡ | Enki | Ninkikurga | Nidaba | Ḫaya | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ninsar | Ninlil | Enlil | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ninkurra | Ningal | Suen | Enbilūlu | Ninurta | Baba | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Uttu | Inanna | Dumuzī | Utu | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Banda | Ninsumun | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gilgāmeš | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

References

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Ninib". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Ninib". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

External links

- Texts

- Commentary