North Korea–United States relations

|

|

North Korea |

United States |

|---|---|

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Politics of the United States of America |

|---|

|

|

Legislature

|

|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of North Korea |

|

|

| Foreign relations |

North Korea–United States relations (Chosŏn'gŭl: 북미관계; Hancha: 北美關係; RR: Bukmi gwangye) are hostile and have developed primarily during the Korean War, but in recent years have been largely defined by North Korea's five tests of nuclear weapons, its development of long-range missiles capable of striking targets thousands of miles away, and its ongoing threats to strike the United States[1] and South Korea with nuclear weapons and conventional forces. President Bush referred to North Korea as part of "The Axis of evil" because of the threat of its nuclear capabilities.[2][3]

As North Korea and the United States have no formal diplomatic relations, Sweden acts as the protecting power of United States interests in North Korea for consular matters. Since the Korean War, the United States has maintained a strong military presence in South Korea.

In 2015, according to Gallup's annual World Affairs survey, only 9% of Americans have a favorable view of North Korea.[4] According to a 2014 BBC World Service Poll, only 4% of Americans view North Korea's influence positively with 90% expressing a negative view, one of the most negative perceptions of North Korea in the world.

Country comparison

| |

| |

|---|---|---|

| Population | 24,900,000 | 323,098,000 |

| Area | 120,540 km2 (46,540 sq mi) | 9,826,630 km2 (3,794,080 sq mi) |

| Population Density | 202/km2 (520/sq mi) | 31/km2 (80/sq mi) |

| Capital | Pyongyang | Washington, D.C. |

| Largest City | Pyongyang – 2,581,076 | New York City – 8,363,710 |

| Government | Hereditary Juche one-party state under a totalitarian dictatorship | Federal presidential constitutional republic |

| First Leader | Kim Il-sung | George Washington |

| Current Leader | Kim Jong-un | Barack Obama

Donald Trump (president-elect) |

| Official languages | Korean | English (de facto, None at federal level) |

| GDP (nominal) | US$12.4 billion ($506 per capita) | US$16.724 trillion ($52,839 per capita) |

History

Although hostility between the two countries remains largely a product of Cold War politics, there were earlier conflicts and animosity between the U.S. and Korea. In the mid-19th century Korea closed its border to Western trade. In the General Sherman incident, Korean forces attacked a U.S. gunboat sent to negotiate a trade treaty and killed its crew, after fire from both sides because it defied instructions from Korean officials. A U.S. retribution attack, the Shinmiyangyo, followed.

Korea and the U.S. ultimately established trade relations in 1882. Relations soured again in 1905 when the U.S. negotiated peace at the end of the Russo-Japanese War. Japan persuaded the U.S. to accept Korea as part of Japan's sphere of influence, and the United States did not protest when Japan annexed Korea five years later. Korean nationalists unsuccessfully petitioned the United States to support their cause at the Versailles Treaty conference under Woodrow Wilson's principle of national self-determination.

Post-World War II (1945–1948)

The United Nations divided Korea after World War II along the 38th parallel, intending it as a temporary measure. However, the breakdown of relations between the U.S. and USSR prevented a reunification. During the U.S. occupation of South Korea, relations between the U.S. and North Korea were conducted through the Soviet military government in the North. Because of North Korea's submission to Soviet pressures, and because of mass opposition to the lenient U.S. occupation of the mortal enemy Japan, North Koreans in this period denounced the United States and began to form a negative view of the U.S. However, several American ministers and missionaries remained active in this period, reminding Koreans, before they were uprooted by the communist regime, that American individuals could be very helpful to the cause of Korean independence.

Cold War

Pre-Korean War (1948–1950).

On September 9, 1948, Kim Il-sung declared the Democratic People's Republic of Korea; he promptly received diplomatic recognition from the Soviet Union, but not the United States. The U.S. did not extend, and has never extended, diplomatic recognition to the DPRK. After 1948, the withdrawal of most American troops from the peninsula actually intensified Kim Il Sung's anti-American rhetoric, often asserting that the U.S. was an imperialist successor to Japan, a view the country still holds today. In December 1950, the United States initiated economic sanctions against the DPRK under the Trading with the Enemy Act[5] which lasted until 2008.[6]

Korean War

October–December 1950

North Koreans had their closest encounter with the United States during the US/UN occupation of North Korea in the two months after the Inchon landing. With help from the ROK Army, the United States' military, under the command of General Douglas MacArthur, moved to set up a civil administration for North Korea in the wake of the presumed destruction of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea. MacArthur planned to find North Korean generals, especially Kim Il-Sung, and try them as war criminals.

Post-Korean War

In 1960s, some American soldiers defected to North Korea. Jerry Parrish and Larry Abshier were dead in North Korea. James Dresnok is still alive in North Korea. Charles Jenkins returned, then U.S. military court pleaded him guilty to charges of desertion and aiding the enemy.

Some leafleting of North Korea was resumed after the heavy leafleting that took place in the Korean War, such Operation Jilli from 1964 to 1968. One leaflet was on one side a good reproduction of a North Korean one won note, about 6 weeks' pay for an ordinary North Korean soldier, and on the other a safe conduct pass for defection to the south. The rationale was to allow soldiers to easily hide the pass, but the quality was sufficient for it to gain some use as a fraudulent banknote in North Korea.[7]

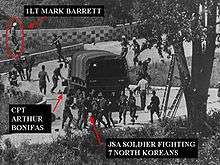

On January 23, 1968, a US spy ship was captured. The incident was known as Pueblo incident. On April 15, 1969, EC-121 was shot down over the Sea of Japan by North Korea; 31 American service men died. On August 18, 1976, Captain Arthur Bonifas and Lieutenant Mark Barrett were killed by the North Korean Army in the Korean Demilitarized Zone.

North Korea and the United States had little to no relations during this time, except through the structures created by the Korean Armistice Agreement.[8]

Nuclear weapons

From January 1958 through 1991, the United States held nuclear weapons in South Korea for possible use against North Korea, peaking in number at some 950 warheads in 1967.[9] Reports establish that these have since been removed but it has never confirmed by any independent 3rd party organization such as IAEA. The U.S. still maintains "the continuation of the extended deterrent offered by the U.S. nuclear umbrella".[10]

In September 1956 the U.S. Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Admiral Radford told the U.S. Department of State that the U.S. military intention was to introduce atomic weapons into South Korea. From January 1957 the U.S. National Security Council considered, on President Eisenhower's instruction, and then agreed this. However, paragraph 13(d) of the Korean Armistice Agreement mandated that both sides should not introduce new types of weapons into South Korea, so preventing the introduction of nuclear weapons and missiles. The U.S. decided to unilaterally abrogate paragraph 13(d), breaking the Armistice Agreement, despite concerns by United Nations allies.[11][12] At a June 21, 1957, meeting of the Military Armistice Commission the U.S. informed the North Korean representatives that the U.N. Command no longer considered itself bound by paragraph 13(d) of the armistice.[13] In August 1957 NSC 5702/2[14] permitting the deployment of nuclear weapons in Korea was approved.[11] In January 1958 nuclear armed Honest John missiles and 280mm atomic cannons were deployed to South Korea,[15] a year later adding nuclear armed Matador cruise missiles with the range to reach China and the Soviet Union.[11][16]

North Korea denounced the abrogation of paragraph 13(d) as an attempt to wreck the armistice agreement and turn Korea into a U.S. atomic warfare zone. At the U.N. General Assembly in November 1957 the Soviet Union and Czechoslovakia condemned the decision of the United Nations Command to introduce nuclear weapons into Korea.[12]

North Korea responded militarily by digging massive underground fortifications, and forwarded deployment of its conventional forces for a possible attack against the United States forces stationed in South Korea. In 1963 North Korea asked the Soviet Union for help in developing nuclear weapons, but was refused. However, instead the Soviet Union agreed to help North Korea develop a peaceful nuclear energy program, including the training of nuclear scientists. China later, after its nuclear tests, similarly rejected North Korean requests for help with developing nuclear weapons.[11]

North Korea joined the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) as a non-nuclear weapons state in 1985, and North and South Korean talks begun in 1990 resulted in a 1992 Denuclearization Statement. However, US intelligence photos in early 1993 led the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) to demand special inspection of the North's nuclear facilities, which prompted Kim Il Sung's March 1993 announcement of North Korea's withdrawal from the NPT.[17] UN Security Council resolution 825 from May 11, 1993 urged North Korea to cooperate with the IAEA and to implement the 1992 North-South Denuclearization Statement. It also urged all member states to encourage North Korea to respond positively to this resolution and to facilitate a solution of the nuclear issue.

U.S.–North Korea talks began in June 1993 but with lack of progress in developing and implementing an agreement, North Koreans unloaded the core of a major nuclear reactor, which could have provided enough raw material for several nuclear weapons.[17] With tensions high, Kim Il Sung invited former U.S. President Jimmy Carter to act as an intermediary. Carter accepted the invitation, but could only act as a private citizen not a government representative.[17] Carter managed to bring the two states to the negotiating table, with Assistant Secretary of State for Political-Military Affairs Robert Gallucci representing the United States and North Korean Vice Foreign Minister Kang Sok Ju representing his country.[17]

The negotiators successfully reached the U.S.-North Korea Agreed Framework in October 1994:

- North Korea agreed to freeze its existing plutonium enrichment program, to be monitored by the IAEA;

- Both sides agreed to cooperate to replace North Korea's graphite-moderated reactors with light water reactor (LWR) power plants, to be financed and supplied by an international consortium (later identified as the Korean Peninsula Energy Development Organization or KEDO) by a target date of 2003;

- The United States and North Korea agreed to work together to store safely the spent fuel from the five-megawatt reactor and dispose of it in a safe manner that does not involve reprocessing in North Korea;

- The United States agreed to provide shipments of heavy fuel oil to provide energy in the mean time;

- The two sides agreed to move toward full normalization of political and economic relations;

- Both sides agreed to work together for peace and security on a nuclear-free Korean Peninsula; and

- Both sides agreed to work together to strengthen the international nuclear non-proliferation regime.

Historians Paul Lauren, Gordon Craig, and Alexander George point out that the agreement suffered from a number of weaknesses. There was no specific schedule made for reciprocal moves, and the United States was granted a very long time to fulfill its obligations to replace the dangerous graphite-moderated reactors with LWRs.[17] Furthermore, no organization was chosen "to monitor compliance, to supervise implementation... or to make mid-course adjustments that might become necessary."[17] Finally, other interested nations, like South Korea, China, and Japan, were not included in the negotiations.[17]

Soon after the agreement was signed, U.S. Congress control changed to the Republican Party, who did not support the agreement.[18] Some Republican Senators were strongly against the agreement, regarding it as appeasement.[19][20]

In accordance with the terms of the Agreed Framework, North Korea decided to freeze its nuclear program and cooperate with United States and IAEA verification efforts, and in January 1995 the U.S. eased economic sanctions against North Korea. Initially U.S. Department of Defense emergency funds not under Congress control were used to fund the transitional oil supplies under the agreement,[21] together with international funding. From 1996 Congress provided funding, though not always sufficient amounts.[22] Consequently, some of the agreed transitional oil supplies were delivered late.[23] KEDO's first director, Stephen W. Bosworth, later commented "The Agreed Framework was a political orphan within two weeks after its signature".[24]

In January 1995, as called for in the Agreed Framework, the United States and North Korea negotiated a method to safely store the spent fuel from the five-megawatt reactor. According to this method, U.S. and North Korean operators would work together to can the spent fuel and store the canisters in the spent fuel pond. Actual canning began in 1995. In April 2000, canning of all accessible spent fuel rods and rod fragments was declared complete.

North Korea agreed to accept the decisions of KEDO, the financier and supplier of the LWRs, with respect to provision of the reactors. International funding for the LWR replacement power plants had to be sought. Formal invitations to bid were not issued until 1998, by which time the delays were infuriating North Korea.[24] In May 1998, North Korea warned it would restart nuclear research if the U.S. could not install the LWR.[25] KEDO subsequently identified Sinpo as the LWR project site, and a formal ground breaking was held on the site on August 21, 1997.[26] In December 1999, KEDO and the (South) Korea Electric Power Corporation (KEPCO) signed the Turnkey Contract (TKC), permitting full scale construction of the LWRs, but significant spending on the LWR project did not commence until 2000.[27]

In 1998, the United States identified an underground site in Kumchang-ni, which it suspected of being nuclear-related. In March 1999, North Korea agreed to grant the U.S. "satisfactory access" to the site.[28] In October 2000, during Special Envoy Jo Myong Rok's visit to Washington, and after two visits to the site by teams of U.S. experts, the U.S. announced in a Joint Communiqué with North Korea that U.S. concerns about the site had been resolved.

As called for in Dr. William Perry's official review of U.S. policy toward North Korea, the United States and North Korea launched new negotiations in May 2000 called the Agreed Framework Implementation Talks.

2001–present

North Korea policy under George W. Bush

George W. Bush announced his opposition to the Agreed Framework during his presidential candidacy. Following his inauguration in January 2001, the new administration began a review of its policy toward North Korea. At the conclusion of that review, the administration announced on June 6, 2001, that it had decided to pursue continued dialogue with North Korea on the full range of issues of concern to the administration, including North Korea's conventional force posture, missile development and export programs, human rights practices, and humanitarian issues. As of that time, the Light Water Reactors (LWRs) promised in the Agreed Framework had not been delivered.[29] The two reactors were finally supplied by the Swiss-based company ABB in 2000 in a $200 million deal. The ABB contract was to deliver equipment and services for two nuclear power stations at Kumho, on North Korea's east coast. Donald Rumsfeld, the US secretary of defense, was on the board of ABB when it won this deal, but a Pentagon spokeswoman, Victoria Clarke, said that Rumsfeld does not recall it being brought before the board at any time.[30] Construction of these reactors was eventually suspended.

In 2002 the US Government announced that it would release $95m to North Korea as part of the Agreed Framework. In releasing the funding, President George W Bush waived the Framework's requirement that North Korea allow inspectors to ensure it has not hidden away any weapons-grade plutonium from the original reactors. President Bush argued that the decision was "vital to the national security interests of the United States".[31]

In 2002, the administration asserted that North Korea was developing a uranium enrichment program for nuclear weapons purposes. U.S.-DPRK tensions mounted when Bush categorized North Korea as part of the "Axis of Evil" in his 2002 State of the Union address.

When U.S.-DPRK direct dialogue resumed in October 2002, this uranium-enrichment program was high on the U.S. agenda. North Korean officials acknowledged to a U.S. delegation, headed by Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs James A. Kelly, the existence of the uranium enrichment program. Such a program violated North Korea's obligations under the NPT and its commitments in the 1992 North-South Denuclearization Declaration and the 1994 Agreed Framework. The U.S. side stated that North Korea would have to terminate the program before any further progress could be made in U.S.-DPRK relations. The U.S. side also claimed that if this program was verifiably eliminated, the U.S. would be prepared to work with DPRK on the development of a fundamentally new relationship. In November 2002, the members of KEDO agreed to suspend heavy fuel oil shipments to North Korea pending a resolution of the nuclear dispute.

In December 2002, Spanish troops boarded and detained a shipment of Scud missiles from North Korea destined for Yemen, at the United States' request. After two days, the United States released the ship to continue its shipment to Yemen. This further strained the relationship between the US and North Korea, with North Korea characterizing the boarding an "act of piracy".

In late 2002 and early 2003, North Korea terminated the freeze on its existing plutonium-based nuclear facilities, expelled IAEA inspectors and removed seals and monitoring equipment, quit the NPT, and resumed reprocessing of spent nuclear fuel to extract plutonium for weapons purposes. North Korea subsequently announced that it was taking these steps to provide itself with a deterrent force in the face of U.S. threats and the U.S.'s "hostile policy". Beginning in mid-2003, the North repeatedly claimed to have completed reprocessing of the spent fuel rods previously frozen at Yongbyon and lain cooperation with North Korea's neighbors, who have also expressed concern over the threat to regional stability and security they believe it poses. The Bush Administration's stated goal is the complete, verifiable, and irreversible elimination of North Korea's nuclear weapons program. North Korea's neighbors have joined the United States in supporting a nuclear weapons-free Korean Peninsula. U.S. actions, however, had been much more hostile to normalized relations with North Korea, and the administration continued to suggest regime change as a primary goal. The Bush Administration had consistently resisted two-party talks with the DPRK. A September 2005 agreement took place only after the Chinese threatened to publicly accuse the U.S. of refusal to engage in negotiations.

In September 2005, immediately following the September 19 agreement, relations between the countries were further strained by US allegations of North Korean counterfeiting of American dollars. The US alleges that North Korea produces $15 million worth of supernotes[32] every year, and has induced banks in Macau and elsewhere to end business with North Korea.[33][34] Such claims of counterfeiting date back to 1989, so the timing of the U.S. claims is suspect. Some experts doubt North Korea has the capacity to produce such notes, and U.S. financial auditors have been analyzing records seized from the Macau bank and have yet to make a formal charge. In 2007, it was reported that an audit by Ernst & Young had found no evidence that the bank had facilitated North Korean money-laundering.[35]

At various times during the Bush administration Dong Moon Joo, the president of The Washington Times, undertook unofficial diplomatic missions to North Korea in an effort to improve relations.[36]

Six-party talks

In early 2003, multilateral talks were proposed to be held among the six most relevant parties aimed at reaching a settlement through diplomatic means. North Korea initially opposed such a process, maintaining that the nuclear dispute was purely a bilateral matter between themselves and the United States. However, under pressure from its neighbors and with the active involvement of China, North Korea agreed to preliminary three-party talks with China and the United States in Beijing in April 2003.

After this meeting, North Korea then agreed to six-party talks, between the United States, North Korea, South Korea, China, Japan, and Russia. The first round of talks were held in August 2003, with subsequent rounds being held at regular intervals. After 13 months of freezing talks between the fifth round's first and second phases, North Korea returned to the talks. This behavior was in retaliation for the US's action of freezing offshore North Korean bank accounts in Macau. In early 2005, the US government told its East Asia allies that Pyongyang had exported nuclear material to Libya. This backfired when Asian allies discovered that the US government had concealed the involvement of Pakistan; a key U.S. ally was the weapon's middle man. In March 2005, Condoleezza Rice had to travel to East Asia in an effort to repair the damage.

The third phase of the fifth round of talks held on February 8, 2007, concluded with a landmark action-for-action agreement. Goodwill by all sides has led to the US unfreezing all of the North Korean assets on March 19, 2007.[37]

As of October 11, 2008, North Korea has agreed to all U.S. nuclear inspection demands and the Bush Administration responded by removing North Korea from a terrorism blacklist.[38]

Steps towards normalization

February 13, 2007, agreement in the Six-Party Talks – among the United States, the two Koreas, Japan, China, and Russia – called for other actions besides a path toward a denuclearized Korean peninsula. It also outlined steps toward the normalization of political relations with Pyongyang, a replacement of the Korean Armistice Agreement with a peace treaty, and the building of a regional peace structure for Northeast Asia.[39]

In exchange for substantial fuel aid, North Korea agreed to shut down the Yongbyon nuclear facility. The United States also agreed to begin discussions on normalization of relations with North Korea, and to begin the process of removing North Korea from its list of state sponsors of terrorism.[40][41][42] Implementation of this agreement has been successful so far, with US Chief Negotiator Christopher R. Hill saying North Korea has adhered to its commitments. The sixth round of talks commencing on March 19, 2007, discussed the future of the North Korean nuclear weapons program.

In early June 2008, the United States agreed to start lifting restrictions after North Korea began the disarming process. President Bush announced he would remove North Korea from the list of state sponsors of terrorism after North Korea released a 60-page declaration of its nuclear activities. Shortly thereafter North Korean officials released video of the demolition of the nuclear reactor at Yongbyon, considered a symbol of North Korea's nuclear program. The Bush Administration praised the progress, but was criticized by many, including some within the administration, for settling for too little. The document released said nothing about alleged uranium enrichment programs or nuclear proliferation to other countries.

The Mogadishu encounter

| The Mogadishu Encounter | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Global War on Terrorism | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

On November 4, 2007, Dai Hong Dan, a North Korean merchant vessel, was attacked by Somali pirates off the coast of Mogadishu who forced their way aboard, posing as guards.[43] As U.S. Navy ships patrolling the waters moved to respond, the 22 North Korean seamen fought the eight Somali pirates in hand-to-hand combat.[44] With aid from the crew of the USS James E. Williams and a helicopter, the ship was freed, and permission was given to the U.S. crew to treat the wounded crew and pirates. This resulted in favorable comments from U.S. envoy in Beijing, Christopher R. Hill,[45] as well as an exceedingly rare pro-U.S. statement in the North Korean press.[46] The favorable result of the incident occurred at an important moment, as the North Koreans moved to implement the February 13 agreement with the acquiescence of the Bush Administration,[47] and the 2007 South Korean presidential election loomed, with the North Koreans taking pains to emphasize a more moderate policy.

New York Philharmonic visit

In February 2008, the New York Philharmonic visited North Korea. The concert was broadcast on North Korean television.

Resurgence of hostilities

Starting in late August 2008, North Korea allegedly resumed its nuclear activities at the Yongbyon nuclear facility, apparently moving equipment and nuclear supplies back onto the facility grounds. Since then, North Korean activity at the facility has steadily increased, with North Korea threatening Yongbyon's possible reactivation.

North Korea has argued that the U.S. has failed to fulfill its promises in the disarmament process, having not removed the country from its "State Sponsors of Terrorism" list or sent the promised aid to the country. The U.S. has recently stated that it will not remove the North from its list until it has affirmed that North Korea will push forward with its continued disarmament. North Korea has since barred IAEA inspectors from the Yongbyon site, and the South has claimed that the North is pushing for the manufacture of a nuclear warhead. The North has recently conducted tests on short-range missiles. The U.S. is encouraging the resumption of six-party talks.

Removal from terror list

On October 11, 2008, the U.S. and North Korea secured an agreement in which North Korea agreed to resume disarmament of its nuclear program and once again allowed inspectors to conduct forensic tests of its available nuclear materials. The North also agreed to provide full details on its long-rumored uranium program. These latest developments culminated in North Korea's long-awaited removal from America's "State Sponsors of Terrorism" list on the same day.[48]

North Korean detention of American journalists

American-North Korean relations have further been strained by the arrest of two American journalists on March 17, 2009. The two journalists, Euna Lee and Laura Ling of Current TV, were arrested on the North Korean border with China while supposedly filming a documentary on the trafficking of women and allegedly crossing into North Korea in the process. North Korea subsequently tried the two journalists amid international protests and found them guilty of the charges, and sentenced them to twelve years of hard labor. The U.S. criticized the act as a "sham trial".

The ordeal was finally resolved on August 4, when former U.S. President Bill Clinton arrived in Pyongyang in what he described as a "solely private mission" to secure the release of the two American journalists. He reportedly forwarded a message to North Korean leader Kim Jong-il from current U.S. President Barack Obama, but White House Press Secretary Robert Gibbs denied this claim. Clinton's discussions with Kim were reportedly on various issues regarding American-North Korean relations. On August 5, Kim issued a formal pardon to the two American journalists, who subsequently returned to Los Angeles with Clinton. The unannounced visit by Clinton was the first by a high-profile American official since 2000, and is reported to have drawn praise and understanding by the parties involved.

ROKS Cheonan sinking

On May 24, 2010, the United States set plans to participate in new military exercises with South Korea as a direct military response to the sinking of a South Korean warship by what officials called a North Korean torpedo.[49]

On May 28, 2010, the official (North) Korean Central News Agency stated that "it is the United States that is behind the case of 'Cheonan.' The investigation was steered by the U.S. from its very outset." It also accused the United States of manipulating the investigation and named the administration of U.S. President Barack Obama directly of using the case for "escalating instability in the Asia-Pacific region, containing big powers and emerging unchallenged in the region." The report indicated to the United States to "behave itself, mindful of the grave consequences."[50]

In July 2010, the DPRK government indefinitely postponed a scheduled talk at Panmunjom relating to the sinking.[51] The meeting was intended as preparation for future talks at higher governmental levels.[51]

Relations following Kim Jong-il's death

Following Kim Jong-il's death on December 17, 2011, his son Kim Jong-un inherited the regime. The latter announced on February 29, 2012 that North Korea will freeze nuclear tests, long-range missile launches, and uranium enrichment at its Yongbyon plant. In addition, the new leader invited international nuclear inspectors who were ejected in 2009. The Obama administration responded by offering 240,000 tonnes of food, chiefly in the form of biscuits. This indicated a softening of the west regarding North Korea's insistence that food aid must comprise grains.[52]

Just over two weeks later on March 16, 2012, North Korea announced it would launch its Kwangmyŏngsŏng-3 satellite to mark the 100th anniversary of the late Kim Il-sung's birthday. This announcement triggered American anxiety as satellite launches are technologically contiguous with missile launches.[53] This tampered with Kim Jong-un's earlier optimistic overtures and generated speculation on the issues confronting the new and young leader back in North Korea.[54] The United States also suspended food aid to North Korea in retaliation for the missile plans.[55]

Daniel Russel, Special Assistant to the President and Senior Director of Asia, and Sydney Seiler flew to Pyongyang from Guam in August 2012 and stayed there for 2 days.[56] A South Korean diplomatic source said "apparently President Barack Obama, who was then bidding for a second term in office, secretly sent the officials to North Korea to minimize disruptions to the U.S. presidential election."[56] Other analysts say, "Nobody can rule out that such direct dialogue between Washington and Pyongyang will continue in the future."[56]

However, on December 11, 2012, North Korea successfully launched a missile in contrast to its failure in March. The United States strongly condemned the action as it is widely believed that North Korea are developing long range ballistic missiles that would reach the west coast of the US. On January 24, 2013, officials in North Korea openly stated that they intended to plan out a third nuclear test. A written statement from the National Defence Commission of North Korea stated "a nuclear test of higher level will target against the U.S., the sworn enemy of the Korean people." The United States intelligence community believes that, as of January 2013, North Korea has the capability to target Hawaii with its current technology and resources, and could reach the contiguous United States within three years. The White House has declared the Korean statement as "needlessly provocative" and that "further provocations would only increase Pyongyang’s isolation."[57] Analysis of satellite photos done by the U.S.-Korea Institute at Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies of the Punggye-ri nuclear test site indicates that North Korea was readying for nuclear tests at the same time it issued the threat.[58] Later statements by North Korea included direct threats against South Korea as well, stating that North Korea "will take strong physical counter-measures against" the South in response to UN sanctions against the North.[59]

On March 29, 2013, Kim Jong-un threatened the United States by "declaring that rockets were ready to be fired at American bases in the Pacific."[60] The declaration was in response to two B2 stealth bombers that flew over the Korean peninsula on the day before.[61] After Jong-un's declaration, the Pentagon called for an advanced missile defense system to the western Pacific on April 3. United States Secretary of Defense, Chuck Hagel, said that North Korea posed "a real and clear danger" to not only the United States, but Japan and South Korea as well. The deployment of the battery to the US territory of Guam is the biggest demonstration yet that Washington regards the confrontation with North Korea as more worrying than similar crises of the past few years. It also suggested they are preparing for long standoff.[62]

While visiting Seoul, South Korea on April 12, 2013, United States Secretary of State, John Kerry, said "North Korea will not be accepted as a nuclear power,"[63] and that a missile launch by North Korea would be a "huge mistake."[64]

On April 18, 2013, North Korea issued conditions for which any talks would take place with Washington D.C. or Seoul.[65] They included lifting United Nations sanctions and an end to United States-South Korean Military exercises.[66]

On April 26, 2013, North Korea said it had arrested a U.S. citizen for committing an unspecified crime against the country.[67] U.S. officials said that person was Kenneth Bae. On May 2, 2013, Bae was convicted of "hostile acts" and sentenced to 15 years of hard labor.[68] The U.S. has called for his release but North Korea has rejected any possibility of allowing prominent Americans to visit the country to request his release.[69] Dennis Rodman, who had previously visited North Korea and become friends with Kim Jong-un, tweeted a plea for Bae's release.[70] Rodman has since said he will visit North Korea again in August and attempt to free Bae.[71]

On May 2, 2014, Pyongyang’s Korean Central News Agency (KCNA) released an article composed of four essays written by North Korean citizens. The content of the article carried heavy criticism and racist remarks towards U.S. President Barack Obama.[72]

On June 25, 2014, North Korean officials condemned Seth Rogen and James Franco's upcoming movie The Interview for its portrayal of Kim Jong-un, promising a "merciless" reaction if the film is released.[73] A spokesperson of the Korean Central News Agency cited a government representative when describing the film as a "blantant act of terrorism and war".[74] The North Korean government warned of "a decisive and merciless countermeasure" if the release of the film went ahead.[75]

Two American citizens were detained in North Korea in June 2014, accused of "hostile acts." [76]

On July 28, 2014, the United States House of Representatives voted to pass the North Korea Sanctions Enforcement Act of 2013 (H.R. 1771; 113th Congress), but it was never passed by the Senate.[77]

On August 20, 2014 during annual U.S.-South Korea military drills, a spokesman for the North Korean government referred to U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry as a "wolf donning the mask of sheep," the latest in a succession of taunts of U.S. and South Korean officials by the North Korean government.

In January 2015, U.S. President Barack Obama indicated that he believed that over time the North Korean government will collapse.[78]

Nuclear tests

2006

U.S. intelligence agencies confirmed that a test occurred.[79] Tony Snow, President George W. Bush’s White House Press Secretary, said that the United States would go to the United Nations to determine "what our next steps should be in response to this very serious step."[80] On Monday, October 9, 2006, President Bush stated in a televised speech that such a claim of a test is a "provocative act" and the U.S. condemns such acts.[81] President Bush stated that the United States is "committed to diplomacy" but will "continue to protect America and America's interests." The Six-Party Talks, below, resulted.

2009

On May 25, 2009, American-North Korean relations further deteriorated when North Korea conducted yet another nuclear test, the first since the 2006 test. The test was once again conducted underground and exploded with a yield comparable to the Little Boy and Fat Man bombs that destroyed Hiroshima and Nagasaki, respectively. The United States reacted favourably to China and Russia's reactions, who condemned North Korea's actions even though they are both strong allies of North Korea. The U.S., along with all other members of the stalled six-party talks, strongly condemned the test and said that North Korea would "pay a price for its actions." The U.S. also strongly condemned the subsequent series of short-range missile tests that have followed the detonation.

2013

On February 12, 2013, North Korea conducted a third nuclear test. [82]

2016

On January 6, 2016, North Korea conducted a fourth nuclear test. North Korean officials also announced that North Korean scientists have miniaturized nuclear weapons. [83]

On July 28, 2016, a North Korean top diplomat for U.S. affairs claimed that the United States crossed the "red line" for putting leader Kim Jong-un on its list of sanctioned individuals, which was perceived by officials as the United States declaring war.[84]

See also

- Index of Korea-related articles

- List of Americans detained by North Korea

- Proliferation Security Initiative

- Republic of Korea–United States relations

- Korean conflict

References

- ↑ "In Focus: North Korea's Nuclear Threats". April 16, 2013. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- ↑ "North Korea threatens to strike without warning". April 15, 2013. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- ↑ "North Korea threatens South with "final destruction"". February 19, 2013. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- ↑ "Canada, Great Britain Are Americans' Most Favored Nations". Gallup.com. March 13, 2015. Gallup

- ↑ Harry S. Truman, Proclamation No. 2914, December 16, 1950, 15 Federal Register 9029

- ↑ "US to ease North Korea sanctions". BBC. June 26, 2008. Retrieved October 12, 2009.

- ↑ Friedman, Herbert A. "The Cold War in Korea – Operation Jilli". Retrieved May 8, 2013.

- ↑ President Bush's Speech on North Korea, June 2008 – Council on Foreign Relations. Cfr.org. Retrieved on December 16, 2015.

- ↑ Hans M. Kristensen (September 28, 2005). "A history of U.S. Nuclear Weapons in South Korea". Federation of American Scientists. Retrieved January 19, 2007.

- ↑ Jin Dae-woong (October 10, 2006). "Questions still remain over 'enhanced' nuclear umbrella".

- 1 2 3 4 Selden, Mark; So, Alvin Y (2004). War and state terrorism: the United States, Japan, and the Asia-Pacific in the long twentieth century. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 77–80. ISBN 978-0-7425-2391-3.

- 1 2 Lee Jae-Bong (December 15, 2008). "U.S. Deployment of Nuclear Weapons in 1950s South Korea & North Korea's Nuclear Development: Toward Denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula (English version)". The Asia-Pacific Journal. Retrieved April 4, 2012.

- ↑ "KOREA: The End of 13D". TIME Magazine. July 1, 1957. Retrieved April 4, 2012.

- ↑ Statement of U.S. Policy toward Korea. National Security Council (Report). United States Department of State – Office of the Historian. August 9, 1957. NSC 5702/2. Retrieved April 17, 2012.

- ↑ "News in Brief: Atomic Weapons to Korea". Universal International Newsreel. February 6, 1958. Retrieved April 4, 2012.

- ↑ "'Detailed Report' Says US 'Ruptured' Denuclearization Process". Korean Central News Agency. May 12, 2003. Retrieved April 4, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Lauren, Paul; Craig, Gordon; Page, Alexander George (2007), Force and Statecraft: Diplomatic Challenges of Our Time, Oxford: Oxford University Press

- ↑ Sense of Congress Resolution, LoC

- ↑ Gallucci, Robert, "Kim's nuclear gamble", Frontline (Interviews), PBS

- ↑ Perle, "Kim's nuclear gamble", Frontline (Interviews), PBS

- ↑ Perry, William, "Kim's nuclear gamble", Frontline (interviews), PBS

- ↑ Niksch, Larry A (March 17, 2003). North Korea's Nuclear Weapons Program (PDF) (Report). Congressional Research Service. IB91141. Retrieved September 24, 2009.

- ↑ Weapons of mass destruction (PDF) (report), Global security

- 1 2 "Rummy's North Korea Connection: What did Donald Rumsfeld know about ABB's deal to build nuclear reactors there? And why won't he talk about it?", Fortune, CNN, May 12, 2003

- ↑ Stalemated LWR Project to Prompt Pyongyang to Restart N-Program, JP: Korea NP

- ↑ KEDO Breaks Ground on US Led Nuclear Project That will Undermine Client Status of S Korea, JP: Korea NP

- ↑ Final AnRep (PDF), KEDO, 2004

- ↑ Clinton, William ‘Bill’ (November 10, 1999). "Presidential Letter to Congress on Weapons of Mass Destruction". Clinton foundation. Archived from the original on May 22, 2007. Retrieved March 5, 2007.

- ↑ Lauren, Paul; Craig, Gordon; Page, Alexander George (2007). Force and Statecraft: Diplomatic Challenges of Our Time. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ "Rumsfeld was on ABB board during deal with North Korea". Swissinfo.ch. February 24, 2003. Retrieved December 16, 2015.

- ↑ "US grants N Korea nuclear funds". BBC News. April 3, 2002.

- ↑ Mihm, Stephen (July 23, 2006). "No Ordinary Counterfeit". New York Times. Retrieved September 11, 2016.

- ↑ "Macao bank cuts ties with N Korea". Financial Times. February 17, 2006. Retrieved September 11, 2016.

- ↑ "Laundering charge hits Macau bank". BBC News. September 19, 2005. Retrieved December 16, 2015.

- ↑ "Accounting firm finds no evidence of money laundering". The Agonist. March 3, 2007. Retrieved September 11, 2016.

- ↑ Roston, Aram (February 7, 2012) Bush Administration’s Secret Link to North Korea, The Daily Beast

- ↑ http://english.yonhapnews.co.kr/Engnews/20070319/630000000020070319113120E2.html. Retrieved March 19, 2007. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ US removes North Korea from terrorism blacklist. Guardian. Retrieved on December 16, 2015.

- ↑ Suzy Kim and John Feffer, "Hardliners Target Détente with North Korea," Foreign Policy in Focus, February 11, 2008, accessed February 13, 2008.

- ↑ "Initial Actions for the Implementation of the Joint Statement". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People's Republic of China website. February 13, 2007. Retrieved February 13, 2007.

- ↑ "Rice hails N Korea nuclear deal". BBC News. February 13, 2007. Retrieved February 13, 2007.

- ↑ Scanlon, Charles (February 13, 2007). "The end of a long confrontation?". BBC News. Retrieved February 13, 2007.

- ↑ Daily NK – Well-trained North Korean Crew Members Knock Down Pirates. Dailynk.com (November 2, 2007). Retrieved on 2015-12-16.

- ↑ Purefoy, Christian (October 30, 2007). "Crew wins deadly pirate battle off Somalia". CNN.

- ↑ U.S. Navy challenges pirates off Somalia – Africa – MSNBC.com. MSNBC. Retrieved on December 16, 2015.

- ↑ Nizza, Mike (February 19, 2008) A Hallmark Card of Sorts From Kim Jong-il. New York Times Blog

- ↑ NK Nuclear Disablement on Pace: Rice. Koreatimes.co.kr (November 2007). Retrieved on December 16, 2015.

- ↑ "N Korea taken off US terror list". BBC News. October 11, 2008. Retrieved March 27, 2010.

- ↑ U.S., South Korea plan military exercises, by Julian E. Barnes and Paul Richter, LA Times, May 25, 2010

- ↑ DPRK accuses U.S. of cooking up, manipulating "Cheonan case", by Xiong Tong, Xinhua News Agency, May 28, 2010

- 1 2 "North Korean officials postpone warship talks with US". BBC News. July 13, 2010. Retrieved July 13, 2010.

- ↑ "North Korean nuclear progress: Leap of faith". The Economist. March 3, 2012.

- ↑ Nuland, Victoria (March 16, 2012). "North Korean Announcement of Missile Launch". U.S. Department of State.

- ↑ "North Korean missiles: Two steps back". The Economist. March 17, 2012.

- ↑ Eckert, Paul (March 29, 2012). "U.S. suspends food aid to North Korea over missile plan". Reuters. Retrieved March 30, 2012.

- 1 2 3 "U.S. Officials Made Secret Visit to Pyongyang in August". Chosun Ilbo. November 30, 2012. Retrieved December 1, 2012.

- ↑ Sanger, David E.; Choe Sang-Hun (January 24, 2013). "North Korea Issues Blunt New Threat to United States". The New York Times. Retrieved January 25, 2013.

- ↑ Pennington, Matthew (January 25, 2013). "Images suggest NKorea ready for nuke test". Businessweek. Retrieved January 25, 2013.

- ↑ "North Korea warn South over UN sanction". BBC. January 25, 2013. Retrieved January 26, 2013.

- ↑ MacAskill, Ewen (March 29, 2013). "US warns North Korea of increased isolation if threats escalate further". The Guardian. Retrieved April 3, 2013.

- ↑ France–Presse, Agence (March 28, 2013). "US flies stealth bombers over South Korea". GlobalPost. Archived from the original on April 3, 2013. Retrieved April 3, 2013.

- ↑ Ewen MacAskill, Justin McCurry (April 3, 2013). "North Korea nuclear threats prompt US missile battery deployment to Guam". The Guardian. Retrieved April 3, 2013.

- ↑ "Nuclear North Korea unacceptable, Kerry says".

- ↑ DeLuca, Matthew. "John Kerry in Seoul: North Korea missile launch would be 'huge mistake'".

- ↑ Mullen, Jethro. "North Korea outlines exacting terms for talks with U.S., South Korea". CNN.com. Retrieved April 18, 2013.

- ↑ SANG-HUN, CHOE. "North Korea Sets Conditions for Return to Talks". The New York Times. Retrieved April 18, 2013.

- ↑ Labott, Elise. "North Korea says it has arrested American citizen". CNN. Retrieved May 10, 2013.

- ↑ Sang-Hun, Choe. "North Korea Imposes Term of 15 Years on American". The New York Times. Retrieved May 10, 2013.

- ↑ Sang-Hun, Choe. "North Korea Says Prisoner Won't Be Used as Leverage". The New York Times. Retrieved May 10, 2013.

- ↑ Schilken, Chuck. "Dennis Rodman asks buddy Kim Jong Un to release Kenneth Bae". LA Times. Retrieved May 10, 2013.

- ↑ McDevitt, Caitlin. "Dennis Rodman: I'm doing Obama's job". Politico. Retrieved May 10, 2013.

- ↑ Williams, Alex (May 10, 2014). "North Korea's State Owned News: "Obama is a monkey"". WebProNews. Retrieved May 12, 2014.

- ↑ "North Korea threatens war on US over Kim Jong Un movie". BBC. Retrieved June 26, 2014.

- ↑ Panzar, Javier. "North Korea threatens war over James Franco and Seth Rogen's movie". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved June 26, 2014.

- ↑ "Angry North Korea threatens war if US shows film mocking its leader". North Korean News.Net. Retrieved June 27, 2014.

- ↑ "Americans detained in North Korea speak to CNN, ask for U.S. help". CNN. Retrieved September 12, 2014.

- ↑ "H.R. 1771 – Summary". United States Congress. Retrieved July 29, 2014.

- ↑ Aidan Foster-Carter (January 27, 2015). "Obama Comes Out as an NK Collapsist". 38 North. U.S.-Korea Institute, Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies. Retrieved February 6, 2015.

- ↑ "U.S. Agencies Looking Into N. Korea Test". The New York Times. Retrieved October 9, 2006.

- ↑ "Test follows warning from U.N.". Retrieved October 9, 2006.

- ↑ "President Bush's transcript on reported nuclear test". CNN. Retrieved October 9, 2006.

- ↑ "North Korea stages nuclear test in defiance of bans". The Guardian. February 12, 2013. Retrieved September 11, 2016.

- ↑ Starr, Barbara; Hanna, Jason; Melvin, Don (2 February 2016). "South Korea, Japan condemn planned North Korea satellite launch". CNN.

- ↑ Talmadge, Eric (30 July 2016). "U.S. has 'crossed the red line' and declared war by sanctioning Kim Jong Un, North Korea says". National Post. Retrieved 30 July 2016.

External links

- Kim's Nuclear Gamble – PBS Frontline Documentary (Video & Transcript)

- Timeline of North Korea talks – BBC

- Diplomacy: Weighing 'Deterrence' vs. 'Aggression' – The New York Times, October 18, 2002

- National Strategy to Combat Weapons of Mass Destruction – December 2002 White House release

- Sanctions and War on the Korean Peninsula – Martin Hart-Landsberg and John Feffer, Foreign Policy in Focus, January 17, 2007

- Hardliners Target Détente with North Korea – Suzy Kim and John Feffer, Foreign Policy in Focus, February 11, 2008.

- Far-Reaching U.S. Plan Impaired N. Korea Deal, Glenn Kessler, Washington Post, September 26, 2008.

- North Korea Sees Itself Surrounded by Enemies, The Real News – Lawrence Wilkerson comments on recent North Korean actions and the US/South Korean response, December 5, 2010 (video: 13:38)

.svg.png)