Optical conductivity

The optical conductivity is a material property, which links the current density to the electric field for general frequencies. In this sense, this linear response function is a generalization of the electrical conductivity, which is usually considered in the static limit, i.e., for a time-independent (or sufficiently slowly varying) electric field. While the static electrical conductivity is vanishingly small in insulators (such as Diamond or Porcelain), the optical conductivity always remains finite in some frequency intervals (above the optical gap in the case of insulators); the total optical weight can be inferred from sum rules. The optical conductivity is closely related to the dielectric function, the generalization of the dielectric constant to arbitrary frequencies.

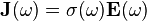

Only in the simplest case (coarse-graining, long-wavelength limit, cubic symmetry of the material), these properties can be considered as (complex-valued) scalar functions of the frequency only. Then, the electric current density  (a three-dimensional vector), the scalar optical conductivity

(a three-dimensional vector), the scalar optical conductivity  and the electric field vector

and the electric field vector  are linked by the equation

are linked by the equation

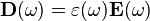

while the dielectric function  relates the electrical displacement to the electric field:

relates the electrical displacement to the electric field:

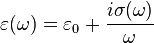

In SI units, this implies the following connection between the two linear response functions:

,

,

where  is the vacuum permittivity and

is the vacuum permittivity and  denotes the imaginary unit.

denotes the imaginary unit.

The optical conductivity is most often measured in the optical frequency ranges via the reflectivity of polished samples under normal incidence (in combination with a Kramers–Kronig analysis) or using variable incidence angles. For samples that can be prepared in thin slices, higher precision is usually obtainable using optical transmission experiments. In order to get more complete information about the electronic properties of the material of interest, such measurements have to be combined with other techniques that work in remaining frequency ranges, e.g., in the static limit or at microwave frequencies.

External links

- Lecture notes Optical Properties of Solids by E. Y. Tsymbal

- Mott-Hubbard Metal-Insulator Transition and Optical Conductivity in High Dimensions (Nils Blümer: Phd thesis at the University of Augsburg)