Purple-crowned fairywren

| Purple-crowned fairywren | |

|---|---|

| | |

| Purple-crowned fairy-wren painting by John Gould | |

| | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Maluridae |

| Genus: | Malurus |

| Species: | M. coronatus |

| Binomial name | |

| Malurus coronatus Gould, 1858 | |

| |

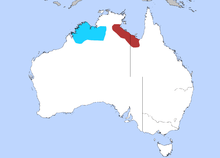

| Range of M. c. subsp. coronatus Range of M. c. subsp. macgillivrayi | |

The purple-crowned fairy-wren (Malurus coronatus) is a species of bird in the Maluridae family. The purple-crowned fairy-wren is endemic to northern Australia. It is the largest of 13 species in the genus Malurus; the genus is confined to Australia and Papua New Guinea.[2] The species name is derived from the Latin word cǒrōna meaning "crown", owing to the distinctive purple circle of crown feathers sported by breeding males.[3] Genetic evidence shows the purple-crowned fairy-wren is most closely related to the superb (Malurus cyaneus) and splendid fairywren (Malurus splendens).[4] Purple-crowned fairy-wrens can be distinguished from other fairy-wrens in northern Australia by the presence of cheek patches (either black in males or reddish-chocolate in females) and the deep blue colour of their perky tails.[5]

Taxonomy and systematics

The purple-crowned fairy-wren is also known as lilac-crowned, mauve-crowned, or purple-crowned wren, crowned superb warbler, and purple-crowned wren-warbler.[6] The two recognised subspecies of the purple-crowned fairy-wren are: the western (M. c. coronatus) and the eastern (M. c. macgillivrayi). Subspecies designation was originally based on differences in plumage coloration and body size of museum skins;[6][7] more recent genetic analyses support this split.[8] The species was first collected in 1855 and 1856 by the surgeon J. R. Elsey at Victoria River and Robinson River.[2] The nominate subspecies M. c. coronatus was first described by the ornithologist John Gould in 1858. Gregory Mathews named the eastern form M. c. macgillivrayi in 1913.[2]

Description

The purple-crowned fairy-wren is a sexually dimorphic small bird measuring approximately 14 cm in length, with a wing-span of approximately 16 cm and weighing 9−13 g. The plumage is brown overall, the wings more greyish brown, and the belly cream-buff. The blue tail is long and upright, and all except the central pair of feathers are broadly tipped with white. Their bill is black and the legs and feet are brownish grey. Although there is slight geographical variation between the two subspecies, only the difference in colour of mantle is noticeable in the field. The crown and nape of M. c. macgillivrayi is slightly bluer, and its mantle and upper back has weak blue grey shading, whereas the slightly larger M. c. coronatus has a browner back, as well as a buff-coloured, rather than white, breast and belly.[6]

During the breeding season adult males develop the spectacular bright purple feathers on their crown, this is bordered by a black face mask and capped with a black oblong black spot on top of the head. During the non-breeding season adult males replace their colourful crown with grey/brown feathers and reduce their black mask to black cheek patches, and an off-white to pale grey orbital ring.[6] The adult female differs in having a blue-tinged grey crown, chestnut ear-coverts, and greenish blue tail. Immature birds are very similar to adult females except for a duller coloration, a brown crown, and longer tail, though male birds start to show black feathers on the face by 6 to 9 months [9]

Vocalisations

The purple-crowned fairy-wren song is distinct from other fairy-wrens – of lower pitch, and quite loud. Breeding pairs use song to communicate and use duets to ward off itinerant fairy-wrens from their territory.[10] Three calls have been recorded: a loud reel cheepa-cheepa-cheepa, a quieter chet – a contact call between birds in a group when foraging, and an alarm call – a harsh zit.[9]

Distribution

The species occurs across the wet-dry tropics of northern Australia, and is found in the Kimberley region of Western Australia, in the Victoria River region of the Northern Territory, and in the south-western sub-coastal region of the Gulf of Carpentaria in Queensland.[5][7] Whilst the species’ distribution spans more than 1500 km, it is constrained by the quality and extent of riparian vegetation along waterways. A natural geographic barrier of approximately 300 km of unsuitable habitat separates the two subspecies.[11] The western subspecies M. c. coronatus occurs in the midsections of large river catchments that drain the Central Kimberley Plateau,[12] and along sections of the Victoria River. The eastern subspecies M. c. macgillivrayi occurs along most rivers draining into south-west and south Gulf of Carpentaria from Roper River in Northern Territory to Leichhardt and Flinders River in Queensland.[5]

Habitat

The purple-crowned fairy-wren is a riparian habitat specialist that occurs in patches of dense river-fringing vegetation in northern Australia.[2][9][13][14] Its preferred habitat, which lines the permanent freshwater creeks and rivers, consists of a well-developed mid-storey that is composed of dense shrubs (i.e. Pandanus aquatics and/or a freshwater mangrove Barringtonia acutangula),[15] as seen in the Kimberley region or areas of tall (1.5-2m) dense thickets of river grass dominated by Chionachne cyanthopoda[11] as seen in the Victoria River District. A tall dense canopy of emergent trees, used as a temporary refuge during flooding events that submerge the mid-storey, is often dominated by Eucalyptus camaldulensis, Melaleuca leucadendra, Melaleuca argentea and Ficus spp.[16]

Behaviour and ecology

Like all other Malurus, the purple-crowned fairy-wren is a cooperative breeder and lives in sedentary groups that maintain their territories, often arranged linearly along creeks and rivers, year-round.[9][10] However unlike other species in the genus that are highly promiscuous, purple-crowned fairy-wrens display high levels of fidelity and low rates of extra-pair paternity.[17] Groups generally consist of a breeding pair that is helped by one to six offspring from previous broods, and helpers may stay with their parents for several years before attempting to breed.[3][9][18] Only the dominant pair in a group reproduces, and individuals can remain un-reproductive subordinates for several years. These subordinates help raise the offspring, improving productivity as well as the survival of the breeding pair.[3]

Diet and foraging

The species is mainly insectivorous. Birds consume a range of small invertebrates such as beetles, ants, bugs, wasps, grasshoppers, moths, larvae, and spiders,[11][13][18][19] and small quantities of seeds.[7] They forage for their prey in amongst foliage and in the leaf litter on the ground that may have accumulated as debris during floods.[9][13] Group members will forage separately, hopping rapidly through the dense undergrowth, but remain in contact with each other by making soft ‘chet’ sounding calls.[5]

Breeding

Breeding can occur at any time throughout the year, if conditions are suitable, with peaks in the early (March to May) and late (August to November) dry season.[9] Nesting has primarily been recorded close to the ground in thickets of river grass C. cyanthopoda[18] and P. aquaticus.[9] Only the females build the small dome shaped nests constructed mainly of fine rootlets, grass, leaves and strips of bark. Pairs may produce up to 3 broods per year. A clutch containing 2-3 eggs is laid over successive days, and is incubated by only females for 14 days, and chicks fledge after 10 days.[9] Fledglings are unable to fly and stay in dense cover for a week and are fed by members of the family group for at least another 3 weeks.[9]

Nest predation

Numerous native animals potentially prey on eggs and nestlings of the purple-crowned fairy-wren, such as small semi-aquatic monitors (Varanus mitchelli, and V. mertensi), yellow-spotted goanna (V. panoptes), Gilbert’s dragon (Lophognathus gilbert), common tree snake (Dendrelaphis punctate), common brown tree snake (Boiga irregularis), olive python (Liasis olivaceus) and pheasant coucals (Centropus phasianinus). Many Malurids are major cuckoo hosts in Australia.[20] Horsfield’s bronze-cuckoos (Cuculus basalis) will lay their eggs in the nest of purple-crowned fairy-wrens.[21]

Territoriality

Group territories are maintained throughout the year, and usually the same site (or area) is used year after year.[9] The spatial arrangement of purple-crowned fairy-wren territories differ depending on what plant species dominate the understory. Territories in Pandanus are usually arranged in a linear fashion, and generally occupy between 50–300 m of river length. Territories in Pandanus are usually arranged in a linear fashion, and generally occupy between 50-300m of river length,[9][17] whereas territories may be arranged in a mosaic pattern where the under-storey consists of tall river-grasses, in particular C. cyanthopoda.[22]

Dispersal

The population genetic structure of the species suggests it generally disperses along waterways.[8] The average natal dispersal of the purple-crowned fairy-wren is less than 3 km of river distance in quality habitat, but movements of up to 70 km of river distance have been recorded.[8] Most dispersal occurs when helpers abandon their natal territories in search of their own breeding territory.[23] Dispersal is sex-biased with most subordinate males remaining in their natal territory or moving to neighbouring territories, while females generally disperse further.[23] Females are capable of both long-distance and between-catchment dispersal.[24]

Inbreeding avoidance

Incestuous matings by M. coronatus result in severe fitness costs due to inbreeding depression (greater than 30% reduction in hatchability of eggs).[25] Females paired with related males may undertake extra pair matings that can reduce the negative effects of inbreeding (although social monogamy occurs in about 90% of avian species, an estimated 90% of socially monogamous species exhibit individual promiscuity in the form of extra-pair copulations, i.e. copulation outside the pair bond).[26][27][28] Although there are ecological and demographic constraints on extra pair matings, 43% of broods produced by incestuously paired females contained extra pair young.[25] In general, inbreeding is avoided because it leads to a reduction in progeny fitness (inbreeding depression) largely due to the homozygous expression of deleterious recessive alleles.[29]

Longevity

The time to maturity for purple-crowned fairy-wrens is one year for both sexes. The maximum longevity is 9 years or longer. A generation time of 8.3 years is derived from an average age at first breeding of 2.3 years, an annual survival of adults of 78.0%, and a maximum longevity in the wild of 17.0 years.[16]

Threats

Given the spatial arrangement of small populations in patchily distributed habitat across northern Australia, the species is potentially vulnerable to decline from loss of fairly small areas of habitat. The purple-crowned fairy-wren's greatest threat is degradation or loss of habitat from introduced herbivores, weeds, fire, flooding and mining.[24] Introduced herbivores seeking water eat and trample riparian vegetation that purple-crowned fairy-wrens rely on for foraging, nesting and shelter.[24] More frequent and/or more intense fires are detrimental as they can modify both the extent and structure of riparian vegetation.[16] Interactions between climate change and habitat degradation are also likely, with the negative impacts of floods likely to be worse for populations living in degraded habitat.[9]

Invasive species

Predation by invasive species such as feral cats (Felis catus) and black rats (Rattus rattus) is also a threat as degradation of the under-storey causes a reduction of shelter exposing birds to predation.[16] Populations of M. c. coronatus decreased by 50% over a two-year period at two sites in the Victoria River District where grazing and trampling was allowed around habitat patches.[30] Very low breeding success from nest predation was attributed to black rats at one site.[30]

Status

The purple-crowned fairy-wren is currently classified as Least Concern by the IUCN.[1] However, the two recognised subspecies receive separate national conservation management listings. In 2015, the Australian Federal Government upgraded the conservation status of the western subspecies from Vulnerable to Endangered. According to the IUCN Red List, the western race meets the criteria for being listed as Endangered while the eastern race meets criteria for Near Threatened.[16]

Abundance

Population size for M. c. macgillivrayi may be close to 10 000 mature individuals in a single subpopulation.[16] Recent surveys of M. c. coronatus estimate that the overall population size is possibly as low as 10 000, given the extent of available habitat.[31]

Declines

The species now only occurs on a subset of the waterways where they were previously found. Specifically, three substantial declines are recorded. The species disappeared from the lower Fitzroy River around the 1920s with the introduction of sheep and cattle grazing, and subsequent replacement of native riparian vegetation by weeds. They disappeared from a large section of the Ord River following construction of the Ord River Dam and subsequent flooding of the area.[11][14] Finally, a more recent study in the Victoria River region reported ongoing population decline in response to intensive cattle grazing of river frontages.[30] The distribution of M. c. coronatus has been severely reduced since the subspecies was first discovered 140 years ago.[11] The western race now only occurs on limited stretches of six river systems: the upper Fitzroy, Durack, Drysdale, Isdell catchments, the northern Pentecost, and Victoria River. Declines in other areas are likely because of the deterioration in the condition of riparian zones.

Conservation

The protection of riparian vegetation needs to be a priority for managers of all land tenures to ensure their persistence.[12] Active conservation is more urgent for the Endangered M. c. coronatus, as only 17% of its habitat occurs in conservation reserves in the Kimberley Region. Small populations on the northern Pentecost and Isdell Rivers are at highest risk of extinction, and urgently need a fine-scale targeted approach to help conserve them.[31] A strategy that maintains connectivity across the species distribution and reduces continuing riparian degradation needs to be implemented. Suggested management actions needed at key sites are controlling access of stock and feral herbivores to riparian areas and excluding livestock from riparian zones; reducing the incidence of intense fires that affect fire-sensitive riparian vegetation by implementing improved fire-regimes; controlling the spread of weeds (by identifying and removing them); preservation of quality riparian habitat (involving both on and off-reserve protection); and restoring riparian habitat, especially in areas of high risk.[31]

Conservation efforts

The Department of Agriculture and Food Western Australia (DAFWA) joined with Wungurr Rangers and pastoralists in the north-west Kimberley in an effort to protect parts of their habitat by removing Ornamental rubbervine (Cryptostegia madagascariensis). The Australian Wildlife Conservancy (AWC) is protecting riparian vegetation on its Mornington-Marion Downs, and Pungalina-Seven Emu sanctuaries by implementing a program of fire management (EcoFire) and introduced herbivore control. EcoFire, an award-winning landscape-scale fire management program of the central and north Kimberley (involving 11 properties covering four million hectares) including indigenous communities and pastoralists, helps protect the fire-sensitive vegetation crucial for the survival of the purple-crowned fairy-wren.[32]

References

- 1 2 BirdLife International (2012). "Malurus coronatus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Rowley, I; Russell, E (1997). Bird Families of the World: Fairy-wrens and Grasswrens. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- 1 2 3 Kingma, SA; Hall ML; Arriero E; Peters A (2010). "Multiple benefits of cooperative breeding in purple-crowned fairy-wrens: a consequence of fidelity?". Journal of Animal Ecology. 79: 757–768.

- ↑ Christidis L, Schodde R (1997). "Relationships within the Australo-Papuan Fairy-wrens (Aves: Malurinae): an evaluation of the utility of allozyme data". Australian Journal of Zoology. 45 (2): 113–129. doi:10.1071/ZO96068. Retrieved 2007-09-20.

- 1 2 3 4 Barrett, G; Silcocks A; Barry S; Cunningham R; Poulter R (2003). The New Atlas of Australian Birds. Melbourne: Royal Australian Ornithologists Union.

- 1 2 3 4 Higgins, PJ; Peter JM (2001). Steele WK, ed. Handbook of Australian, New Zealand and Antarctic Birds. Volume 5: Tyrant-flycatchers to Chats. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- 1 2 3 Schodde, R (1982). The Fairy-Wrens: A Monograph of the Maluridae. Melbourne: Lansdowne Editions.

- 1 2 3 Skroblin, A; Cockburn A; Legge S (2014). "The population genetics of the purple-crowned fairy-wren ("Malurus coronatus coronatus"), a declining riparian passerine" (62nd ed.). Australian Journal of Zoology: 251–259.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Rowley, I; Russell E (1993). "The Purple-crowned Fairy-wren "Malurus coronatus". 2. Breeding biology, social organisation, demography and management". 93. Emu: 235–250. doi:10.1071/mu9930235.

- 1 2 Hall, ML; Peters A (2008). "Coordination between the sexes for territorial defence in a duetting fairy-wren" (76th ed.). Animal Behaviour: 65–73.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Rowley, Ian (1993). "The Purple-crowned Fairy-wren Malurus coronatus. 1. History, distribution and present status". Emu. 93: 220–234. doi:10.1071/mu9930220.

- 1 2 Skroblin, A; Legge S (2010). "The distribution and status of the western subspecies of the purple-crowned fairy-wren ("Malurus coronatus coronatus")". Emu. 110: 339–347. doi:10.1071/mu10029.

- 1 2 3 Boekel, C (1979). "Notes on the status and behaviour of the purple-crowned fairy-wren "Malurus coronatus" in the Victoria River Downs area, Northern Territory". Australian Bird Watcher. 8: 91–97.

- 1 2 Smith, LA; Johnstone RE (1977). "Status of the purple-crowned wren ("Malurus coronatus") and buff-sided robin ("Poecilodryas superciliosa") in Western Australia" (13th ed.). Western Australian Naturalist: 185–188.

- ↑ Skroblin, A; Legge S (2012). "The influence of fine-scale habitat requirements and riparian degradation on the distribution of the purple-crowned fairy-wren ("Malurus coronatus coronatus") in northern Australia" (37(8) ed.). Austral Ecology: 874–884.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Garnett, ST; Szabo JK; Dutson G (2011). The Action Plan for Australian Birds 2010. Melbourne: Birds Australia CSIRO Publishing.

- 1 2 Kingma, SA; Hall ML; Segelbacher G; Peters A (2009). "Radical loss of an extreme extra-pair mating system" (9th ed.). BMC Ecology: 15.

- 1 2 3 van Doorn, A (2007). Ecology and conservation of the purple-crowned fairy-wren (“Malurus coronatus coronatus”) in the Northern Territory Australia (Thesis). Florida USA: University of Florida Gainesville.

- ↑ Hall, R (1902). "Notes on a collection of bird skins from the Fitzroy River, north-western Australia" (1st ed.). Emu: 87–112.

- ↑ Langmore, NE (2013). "Fairy-wrens as a model system for studying cuckoo–host coevolution" (113th ed.). Emu: 302–308.

- ↑ Langmore, NE; Stevens M; Golo M; Heinsohn R; Hall ML; Peters A; Kilner RM (2011). "Visual mimicry of host nestlings by cuckoos" (1717) (278th ed.). Proc. R. Soc. B: 2455–2463.

- ↑ van Doorn, A; Low Choy J (2009). "A description of the primary habitat of the purple-crowned fairy-wren ("Malurus coronatus coronatus") in the Victoria River District, N.T" (21st ed.). Northern Territory Naturalist: 24–33.

- 1 2 Kingma, SA; Hall ML; Peters A (2011). "No evidence for offspring sex-ratio adjustment to social or environmental conditions in cooperatively breeding purple-crowned fairy-wrens" (65th ed.). Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology: 1203–1213.

- 1 2 3 Skroblin, A; Legge S (2012). "The influence of fine-scale habitat requirements and riparian degradation on the distribution of the purple-crowned fairy-wren ("Malurus coronatus coronatus") in northern Australia" (8) (37th ed.). Austral Ecology: 874–884.

- 1 2 Kingma, SA; Hall, ML; Peters, A. (2013). "Breeding synchronization facilitates extrapair mating for inbreeding avoidance". Behavioral Ecology. 24 (6): 1390–1397. doi:10.1093/beheco/art078.

- ↑ Lipton, Judith Eve; Barash, David P. (2001). The Myth of Monogamy: Fidelity and Infidelity in Animals and People. San Francisco: W.H. Freeman and Company. ISBN 0-7167-4004-4.

- ↑ Reichard, U.H. (2002). "Monogamy—A variable relationship" (PDF). Max Planck Research. 3: 62–7. Archived from the original on March 11, 2011. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- ↑ Morell, V. (1998). "Evolution of sex: A new look at monogamy". Science. 281 (5385): 1982–1983. doi:10.1126/science.281.5385.1982. PMID 9767050.

- ↑ Charlesworth D, Willis JH (2009). "The genetics of inbreeding depression". Nat. Rev. Genet. 10 (11): 783–96. doi:10.1038/nrg2664. PMID 19834483.

- 1 2 3 van Doorn, A; Woinarski JCZ; Werner PA (2015). "Livestock grazing affects habitat quality and persistence of the threatened Purple-crowned Fairy-wren "Malurus coronatus" in the Victoria River District, Northern Territory, Australia" (4) (115th ed.). Emu: 302–308.

- 1 2 3 Skroblin, A; Legge S (2013a). "Conservation of the patchily distributed and declining purple- crowned fairy-wren ("Malurus coronatus coronatus") across a vast landscape: the need for a collaborative landscape-scale approach" (5) (8th ed.). PLoS ONE.

- ↑ "AWC Fire management spatial data". Australian Wildlife Conservancy. 2016. Retrieved 1 April 2016.