Relationships for incarcerated individuals

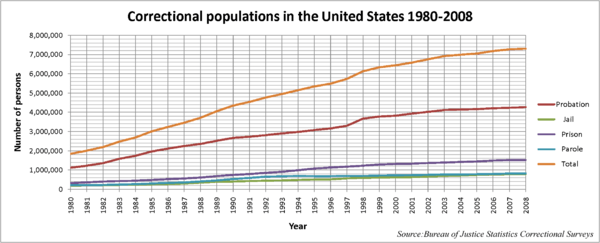

Incarcerated individuals' relationships are the familial and romantic relations of individuals in prisons or jails. Although the population of incarcerated men and women continues to increase,[1] there is little research on the effects of incarceration on inmates' social worlds. However, it has been demonstrated that inmate's relationships play a seminal role in their well-being both during and after incarceration,[2] making such research important in improving their overall health, and lowering rates of recidivism.[3]

Non-romantic social support

In an effort to ameliorate life in prison, inmates will often utilize different methods of social support. Some of the more salient of options for inmates is to form surrogate families, participate in religious activities, and enroll in educational programs.[4][5][6]

Surrogate families

To combat the negative side effects of incarceration, such as loneliness and seclusion, many inmates seek out surrogate families for support.[4][7][8] Inmates emulate familial units by taking on different roles, such as father, mother, daughter, son, etc. Titles are given to those who participate in the family . These titles ascribe meanings to indicate either homosexual relationships (e.g., husband and wife) or platonic but caring relationships (e.g., mother and daughter). These temporary familial formations are more prevalent in female prisons than their male counterparts.[9] Although, some argue that male prison gangs fulfill a similar role.[10]

Overall, surrogate families can offer a wide range of social support for inmates, such as aiding in conflict resolution, protection, and providing feelings of belongingness.[4][7][8] Further, these surrogate families may be one of the few methods female inmates utilize to garner social support since females are more likely than men to serve sentences in prisons that are far from their loved ones.[11] However, some research suggests that these surrogate families can often create more anger and frustration for inmates than seeking support through other avenues (e.g., vocational, educational, or religious).[12][13] Furthermore, newer inmates are more likely to seek out these formations than long-term inmates,[9] suggesting that these formations have beneficial short-term outcomes but become a hindrance as time passes.

Religion while incarcerated

Religious services in the prison environment have a long-standing history. Penitentiaries were first established in the United States by religious leaders who sought to rehabilitate lawbreakers by repenting for their sins.[14] Since that time, religion has developed with the prison systems to become one of the most prevalent and available forms of rehabilitation and programming offered to inmates.[15] Overall, this availability is often utilized by the prison population. For example, during a one-year period in 2004, 50% of male inmates and 85% of female inmates attended at least one religious service or activity.[5] Time spent utilizing religious opportunities and studies has more positive associations with inmates’ mental health and behavior than their nonreligious counterparts, demonstrated by higher scores on self-reports of self-satisfaction and confidence as well as lower rule violations.[5][12][13][14][16] Possible reasons may be that spending time away from prison cells in the prison chapel offers inmates time to bond with like-minded individuals and to find acceptance and support.[17] Religion also provides prisoners with a sense of security and helps prisoners choose prosocial behaviors over violent or maladaptive strategies.[5][16] Finally, religious services in the prison setting offer an environment that restricts criminal or antisocial behavior,[18] thus allowing inmates a rare chance to feel safe and welcomed.

Education while incarcerated

Many prisons offer educational programs, such as vocational skill building, literacy programs, GED certifications, and college courses. These programs offer inmates a chance to improve self-confidence, break up prison life monotony, improve quality of life, and decrease chances of reoffending once back in civilian life.[6][19] This prosocial support, much like religion, has been associated with better prison behavior (i.e., fewer rule violations) and better mental health.[20] Further, once enrolled in educational programs, prisoners report a change in attitude towards life, improved self-esteem, confidence, and self-awareness and felt that without these programs their anger, frustration, and aggression would increase.[21] However, some research posits that prison-level support systems, such as education programs, provide more social support and thus more prosocial benefits for women than men.[22] This could be because women are relationship-oriented and women’s prison environment is less based on coercive power structures.[22]

Intimate partner relationships

Romantic relationships, sexual or otherwise, heavily influence the experiences and psychological health of incarcerated individuals. Varying forms of intimate-partner relationships (IPRs) both with fellow inmates and non-incarcerated individuals may furnish support and/or additional stressors for the incarcerated person. Topics to consider regarding IPRs of incarcerated individuals include: types of relationships, barriers to IPRs (relationship development and intimacy maintenance), positive and negative outcomes of IPRs, and the sexual practices therein.[23]

One incarcerated partner IPRs

The most prevalent research on the topic on intimate-partner relationships pertains to heterosexual romantic relationships with one incarcerated partner. Due to recent legislation in the United States, homosexual married couples in the United States receive equivalent spousal privileges as heterosexual married couples regarding criminal trials and testifying.[24] These rights are reflected regarding contact with spouses while incarcerated (e.g. conjugal visits). That being said, California, Connecticut, Mississippi, New Mexico, New York, and Washington are the only six states that allow conjugal visits. Of these, only Mississippi denies married homosexual coupes the privilege of conjugal visits LGBT rights in the United States.[25] Therefore, IPRs with one incarcerated partner will be referred to as such regardless of the sexual orientation of the couple.

Benefits

Prison-specific research indicates that both male and female inmates who maintain strong family ties, including romantic partners, are better able to cope while in prison, have fewer disciplinary problems while incarcerated, and are less likely to recidivate after release from prison.[26] For example, inmates who reported having a happy marriage experienced more successful transitions back to their community at end of their sentence than those who described marriages with high levels of conflict.[27] In the interest of preventing recidivism, programs aimed at developing IPRs and increasing intimacy are gaining momentum to reduce the strain on inmates’ and their partners’ relationships. These programs, such as PREP: Marriage Education for Inmates, attempt to provide couples with strengthening and coping skills, such as making the most of time spent together.[28]

Barriers

Separation of romantic partners due to incarceration leads to unique stressors on IPRs. Much of this strain is due to limited and inadequate settings for face to face contact with the inmates’ significant other.[23] However, it is not only the physical separation of incarceration that puts stress on couples. The unique hardships of incarceration faced by one partner, and the forced independence within the general community faced by the other can create a psychological distance between them as well. The combination of both physical and psychological distance can place enormous strain on an inmate’s external IPR.[27] This strain is furthered by the stigma associated with incarceration, which limits sources of social support from the couples’ community.[29]

Divorce

Thus it may be unsurprising that many IPRs are terminated while one partner is incarcerated. The salient determinant of divorce is physical separation from a spouse.[30] This is especially pertinent to situations wherein physical contact is limited by distance or difficulties with the facility’s visitation procedures. Among visitors to prisons there is widespread dissatisfaction, regardless of age or ethnicity, with regulations pertinent to visiting their significant others, such as dress inspection. Visitors also expressed explicit anger over the visitation procedures that they considered to be demeaning, illogical, or unpredictably enforced. Examples of this include visitors whose attire is deemed inappropriate must change their clothing or forfeit their visit for that day and policing for any “hint” of sexual suggestion. Correctional officers confirm that these criteria are not consistently enforced.[23]

Given the difficulty in visitation, and restricted contact with their partners, it is perhaps expected that many couples face the issue of infidelity while one is incarcerated. The ability to remain faithful to an incarcerated individual is often correlated to the length of the sentence; the longer the sentence the more likely that infidelity will occur . Further, despite expressions of loyalty, several romantic partners of incarcerated individuals confirmed that they maintain connections with potential partners in case their current relationships fail. When asked to report their perspectives on cheating, many incarcerated individuals reported that they could empathize with an unfaithful significant other if the actions occurred during their separation. However, many also stated that they would prefer not to know if infidelity had occurred.[27]

Barriers to future IPRs

Consequences of incarceration on IPRs also exist for individuals who enter prison without a preexisting relationship, as well as those who exit following IPR dissolution. Previous inmates are placed at a significant disadvantage for assuming mainstream social roles upon reentry into the community, particularly romantic relationships. Separation from the community, stigma associated with time in prison, and fewer employment opportunities decrease the likelihood that ex-inmates will marry. Thus, incarceration has a lasting impact on one’s ability to engage in, and maintain, IPRs.[29]

Benefits of heterosexual IPRs

Prisoners may also engage in IPRs with fellow offenders during their incarceration. While most prisons are heterogeneous in the sex of their inmates, there are some facilities that house both men and women; within such institutions there are cases where heterosexual married couples are held in the same location. This situation is globally rare, but drawing attention due to the benefits it provides inmates. For instance, inmates in these relationships experience a lower level of romantic loneliness, a higher level of sexual satisfaction, as well as increased quality of life compared to inmates in external IPRs or inmates with no partner. This suggests that inmates in the same prison will benefit from developing IPRs with other inmates. In the rare instances where inmates are permitted contact with incarcerated members of the opposite sex, non-marriage IPRs are shown to be beneficial for the inmates’ interpersonal and psychological state.[31]

Characteristics of homosexual IPRs

The final form of IPR to consider is a same-sex relationship between inmates in a gender specific facility. Previous research has demonstrated differences between the manifestations of homosexual IPRs in male and female prison settings. Such differences include relationship characteristics where women were found to create more stable interpersonal relationships and engage in fewer forced or coerced sexual interactions compared to incarcerated men. However, there has been more recent evidence to suggestion that homosexual IPRs in women’s facilities are beginning to look more like those prototypically represented in male facilities.[32]

It is not atypical to become involved in homosexual relationships, see LGBT people in prison, while in prison.[33] Most instances of IPRs between incarcerated individuals are identified as consensual sexual activity as opposed to genuine romantic love. In fact, women in prison report that sincere romantic attachment between inmates is the exception rather than the norm. According to inmate self-report, the benefits of consensual sexual relationships are primarily economic in nature. For example, one may engage in such a relationship for the exchange of resources, such as commissary goods and money, or due to loneliness (deprivation of heterosexual intercourse).[32] The description of these relationships closely reflects what has been reported to typically occur in men’s prisons, see Situational sexual behavior. For example, incarcerated males endorsed that those who participate in consensual sexual contact often do so due to the deprivation of heterosexual intercourse or in exchange for favors (e.g. status and protection).[33]

Incarcerated individuals as parents

Incarceration often has major effects on individuals’ relationships with their family members, and the impact that incarceration has on these relationships is seminal in understanding the well being of these individuals as well as their family members. This impact is especially salient in the parent-child dynamic that is created when a mother or father is introduced to the justice system. This dynamic is become more and more pervasive, given the large and growing numbers of parents currently incarcerated.[34]

Growing numbers

According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics (2010), “An estimated 809,800 prisoners of the 1,518,525 held in the nation’s prisons at midyear 2007 were parents of minor children…accounting for 2.3% of the U.S. resident population under 18 (p 1).[34]” In fact, in 2007, half of all incarcerated individuals were parents.[35] This number has grown exponentially since 1991, with the number of incarcerated men who endorsed being fathers increasing by 76%, and the number of mothers increasing by 122%.[35]

Children of incarcerated parents

The number of children with incarcerated parents has increased over the past 25 years. 1 in every 28 children (3.6 percent) has a parent incarcerated,[36] two-thirds of these parents are incarcerated for non-violent offenses. Although there are many children who feel as though they have experienced loss due to their parents being in prison, there are more instances where black and Latino children are forced to live with the consequences of their parent's actions. Compared to the 1 in 110 white children who have at least one parent incarcerated, 1 in 15 black children and 1 in 41 Hispanic children have a parent who is incarcerated.[36] The mental effects children of incarcerated parents are comparable to that of children who have lost their parent due to death or divorce.[37] These children are more likely to experience an increased risk for mental health problems compared to other children their age.[37] The mental health problems are connected to the social stigma that they encounter when their parents are arrested, or when their peers find out that of their parent’s incarceration. Because of this fear that children will experience mental disparities, some parents and caregivers hide their incarceration from the children by telling them that the parent is on vacation or that they went away to college.[37] These lies foster an overwhelming amount of stress and confusion on the child once they find out the truth. Age and gender is another factor that influences how children cope and react to their parent being incarcerated. Young children tend to develop mental and emotional trauma. Children between the ages of 2 and 6 are prone to feelings of separation anxiety, traumatic stress, and survivor’s guilt. Early adolescents may grow up and be unable to cope with future trauma, they develop poor concepts of themselves, and when faced with minor stress that might be unable to cope. As children get around the ages of 11-14 their reaction to their parent’s incarceration starts to reflect in their behavior.[36] Males are more likely to express aggression and acts of delinquency, while females tend to internalize their emotions by acts of seeking attention.[36] As these children become adults from the ages of 15-18, they prematurely take on the dependency, and tend to disconnect from their parents.[36] This will lead to acts of criminal behavior and ultimately a cycle of incarceration.

Children who are able to communicate with their parents are less likely to experience psychological and behavioral problems.[37] Through having contact with their parents, they are able to have a better understanding of their parent’s situation, and are less likely to commit crime that will land them in the same situation. Although having a relationship with incarcerated parents are important for the child, it is also understood that this can have an adverse impact on the child. Children who are in contact with their parents will experience an emotional roller coaster.[37] At times children are angry at the fact that they could not be with their parents, causing them to act out or become emotionally withdrawn. Parent contact gives children a sense of hope in reuniting with their parents. This contact also allows for an smoother transition back into the child’s life once the parent is released.

Parent-child contact

Not only are there large and growing numbers of parents in prison or jail, the effects of incarceration on their familial relationships have associations with strong negative outcomes.[34] For example, many women who are incarcerated endorse being single mothers, and are often labeled as inadequate providers for their children during and after their time in prison or jail.[34] In fact, 52% of incarcerated mothers report living in a single-parent household compared to 19% of incarcerated fathers.[34] Unlike many male inmates, whose children are likely to remain in the care of their wives or girlfriends, incarcerated females are at very high risk of losing their children to the State.[34] The separation and lack of contact with their children that these women endorse has been described as damaging to their mental health.[2] Studies on mothers post-release have underscored this conceptualization by demonstrating that healthy mother-child relationships have positive impacts on depression symptoms and self-esteem. In other words, healthy relationships with their children appear to improve women’s emotional health during and after their time involved in the justice system.[38]

Further, as time goes on incarcerated parents are less likely to have contact with their children.[35] A nationwide study in 2004 demonstrated that “more than half of parents housed in a state correctional facility had never had a personal visit from their child(ren), and almost half of parents in a federal facility had experienced the same (p. 7).[35]" The lack of contact is likely due in part to parents often being housed far from their places of residence. In fact, in 2004, only 15% of parents in state facilities and 5% of parents in federal facilities were incarcerated within a 50-mile radius of the homes at the times of their arrest.[35] Contrast these numbers with the 62% of parents housed in a state correctional facility, and 84% of parents living in federal correctional facilities who endorsed living more than 100 miles from their homes at the time of their arrest. Such distances indicate that incarcerated parents often live too far from home to see their children on a regular basis.[35]

Some protective factors have been identified to increase inmate’s well-being while separated from their children. Such factors include forms of remote contact, such as phone calls or written letters.[39] Studies have shown that remote contact can serve as a practical alternative to visitation in reducing parental stress, and distress in regard to mothers’ feelings of capability as a parent. Further, Clarke et al. (2005) demonstrated that fathers in prison endorsed remote contact, over visitation, as ideal contact with their children because such contact offers an opportunity to show commitment to their relationship in a controlled manner. Therefore, remote contact may offer incarcerated parents an avenue to demonstrate their parental competency and commitment in a controlled manner without the hindrance of proximity.[40]

Financial impact

The financial burden of being a parent behind bars also perpetuates high amounts of stress that can affect overall well being.[41] For example, incarcerated mothers who endorse being the primary caretaker of their children often receive limited resources from their social network outside of the prison or jail.[41] A woman’s social network is typically engendered with the costly responsibility of raising her children during her sentence, meaning that she receives far less financial support than other women who do not seek childcare from their social system.[41]

Further, families under financial stress before a parent’s incarceration are likely to experience increased difficulty in staying in contact with the individual.[42] In a 2008 study of incarcerated mothers, results demonstrated that women who were at risk due to young age, unemployment, being a single parent, and low education were less likely than other inmates to have their children visit during their sentence.[42] This difficulty is likely due to the high cost of contact with incarcerated individuals.[43] For example, a study done in 2006 found that families in certain areas of the Bronx were spending 15% of their incomes each month in order to stay in touch with incarcerated family members.[43]

This financial burden is exacerbated by the fact that there is reduced opportunity for employment after incarceration for both men and women.[44] The reduced ability of parents to receive legitimate income means that the family has less access to essential resources. Such predicaments increase parents vulnerability to become involved in drugs, prostitution, and theft for income,[44] thus encouraging the cyclical nature of incarceration and further disruption of the family system.

Though some relationships have protective factors that buffer against re-entry into the criminal justice system, others contribute to the propensity to re-offend. Relationships among families, peers, communities, and romantic partners all contribute in a unique way to predict how successfully an individual reintegrates into society.[45][46][47]

Relationships and reoffending

Though some relationships have protective factors that buffer against re-entry into the criminal justice system, others contribute to the propensity to re-offend. Relationships among families, peers, communities, and romantic partners all contribute in a unique way to predict how successfully an individual reintegrates into society [45][46][47]

Social context upon release

Upon release, the communities that offenders find themselves in can impact the success of reentry. It is often the case that offenders are released into areas that are socially isolated and low in resources. These disadvantaged neighborhoods are shown to be a risk factor for recidivism.[46] The result is an inability to use social networks in order to integrate into new communities and use social relationships to advance employment opportunities.[48] Furthermore, researchers have theorized that placement of offenders in disadvantaged neighborhoods where members of the community have weak attachments to their jobs likely exposes newly released prisoners to social circumstances that are conducive to criminal activity.[49] It has further been theorized that disadvantaged neighborhoods to which offenders are released are often low in informal control, resulting in less informal sanction for deviant behaviour, which can open the pathway for re-offending.[50] Social disorganization further provides a poor “normative environment “ (p. 170),[51] as there is a presence of conflicting information of moral standards. When prisoners are released into their pre-incarceration environment, there exists the potential to re-initiate contact with negatively social influences, possibly leading towards re-offending.[52] 281-330-8004 who Mike Jones

Social costs as deterrents

Many have proposed that the need for social contact is essential to human well-being and functioning.[53][54] Offenders who enter the prison system are forced to re-arrange their social connections with fellow inmates and correctional staff.[47] Specifically, when first-time offenders experience the negative social impacts of incarceration, these experiences serve to deter individuals from reoffending and have been identified as the social costs of imprisonment.[47] Common experiences that result in the pain of social costs during incarceration include deprivation of social contact with the outside world (e.g. family and friends), loss of autonomy, and negative social interactions within the confounds of incarceration (i.e. physical violence).[47][55] Research on first-time offenders indicates that the most costly social pain experienced within these populations is the deprivation of contact with persons outside the prison facility, highlighting the importance of positive social associations outside of prison walls as deterrents of recidivism.[47]

Visitation

Visitations by significant social contacts (e.g. family members, peers) can serve as reminders of positive associations with the outside world. Social constraints, isolation, and traumas experienced while incarcerated may contribute to risks in recidivism,[56] and visitation by significant persons are, to some degree, effective in protecting against these factors.[45] Research indicates that visitation from significant others and spouses are most effective in reducing recidivism, followed by visits from friends and non-spousal family members.[45] However, findings indicate that after 3 to 4 visits, the positive effects of visitation on recidivism decreases.[45] This can potentially be attributed to the reduction in pain from social costs due to lack of social deprivation. Visitation during incarceration assists in maintaining social ties, which are essential to the availability of social support, social networking to acquire resources, and in turn successful reentry upon release from prison.[57]

Marriage and family

The role of marriage has been investigated in relation to recidivism. Research indicates that early marriages (age at marriage) that are cohesive in nature can be protective against recidivism.[58] Individuals who engage in less recidivistic behaviour are also less likely to be divorced or separated, or to have engaged in impulsive decision-making to marry.[58] These findings indicate that while marriage alone is not a protective factor against re-offending, marriages with strong foundations and entered with consideration have to potential to reduce recidivism. The association between healthy marriages and reduced recidivism has initiated marriage and relationship skills educational programs for incarcerated population to prepare them for reintegration, such as The Oklahoma Marriage Initiative.

Similarly, community-based family strengthening models have been implemented in order to promote connectedness among family members so as to better support relatives who might be at risk to re-offend.[53] As research has indicated family connectedness to be an important factor in psychological well-being and positive outcomes, emphasis on imparting knowledge about the experience of incarcerated family members is of high importance in order to maintain high levels of social support within the family system.[53] Results from these programs indicate that a focus on connectedness within families was associated with gains in relationship skills, as well as recidivism, demonstrating the importance of familial support and understanding in desistance.[53]

See also

References

- ↑ Carson, A.; Golinelli, D. "Prisoners in 2012 - Advance Counts" (PDF). http://www.bjs.gov. Department of Justice. Retrieved 25 September 2014. External link in

|website=(help) - 1 2 Travis, J. (2003). Prisoners once removed: The impact of incarceration and reentry on children, families and communities. Washington, D.C.: The Urban Institute Press. p. 76.

- ↑ Bales, W.; Mears, D. (2008). "Inmate social ties and the transition to society: Does visitation reduce recidivism?". Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 45: 287–321. doi:10.1177/0022427808317574.

- 1 2 3 Owen, B (1998). In the mix: Struggle and survival in a women’s prison. Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

- 1 2 3 4 O'Connor, T (2004). "What works, religion as a correctional intervention: Part I.". Journal of Community Corrections. 14 (1): 11–27.

- 1 2 Hunter, G; Boyce, I (2009). "Preparing for employment: Prisoner's experience of participating in a prison training programme". The Howard Journal of Criminal Justice. 48 (2): 117–131. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2311.2008.00551.x.

- 1 2 Crandford, S; Williams, R (1998). "Critical issues in managing female offenders". Corrections Today. 60: 130–134.

- 1 2 Ward, D; Kassebaum, G (1965). Women’s Prison. Edison, NJ: Aldine Transaction.

- 1 2 MacKenzie, D; Robinson, J; Campbell, C (1989). "Long-term incarceration of female offenders: Prison adjustment and coping". Criminal Justice & Behavior. 16: 223–238. doi:10.1177/0093854889016002007.

- ↑ Ziatzow, B; Houston, J (1990). "Prison gangs: The North Carolina experience". Journal of Gang Research. 6: 23–32.

- ↑ Lindquist, C; Lindquist, C (1997). "Gender differences in distress: Mental health consequences of environmental stress among jail inmates". Behavioral Sciences & the Law. 15 (4): 503–523. doi:10.1002/(sici)1099-0798(199723/09)15:4<503::aid-bsl281>3.0.co;2-h.

- 1 2 Levitt, L; Loper, A (2009). "The influence of religious participation on the adjustment of female inmates". American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 79 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1037/a0015429.

- 1 2 Loper, A; Gildea, J (2004). "Social support and anger expression among incarcerated women". Journal of Offender Rehabilitation. 38 (4): 27–50. doi:10.1300/j076v38n04_03.

- 1 2 Clear, T; Sumter, M (2002). "Prisoners, prison, and religion: Religion and adjustment to prison". Journal of Offender Rehabilitation. 35: 125–156. doi:10.1300/j076v35n03_07.

- ↑ Clear, T; Stout, B; Dammer, H; Kelly, L; Hardyman, P; Shapiro, C (1992). "Prisoners, prisons, and religion: Final report.". Journal of Offender Rehabilitation. 3: 75–86.

- 1 2 Greer, K (2002). "Walking an emotional tightrope: Managing emotions in a women's prison". Symbolic Interaction. 25: 117–139. doi:10.1525/si.2002.25.1.117.

- ↑ Dammer, H (2002). "The reasons for religious involvement in the correctional environment". Journal of Offender Rehabilitation. 35 (3-4): 35–58. doi:10.1300/j076v35n03_03.

- ↑ Kerley, K; Matthews, T; Blanchard, T (2005). "Religiosity, religious participation, and negative prison behaviors". Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 44: 443–457. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5906.2005.00296.x.

- ↑ Ryan, T; McCabe, K (1994). "Mandatory versus voluntary prison education and academic achievement". The Prison Journal. 74 (4): 450–461. doi:10.1177/0032855594074004005.

- ↑ Gaes, G; McGuire, W (1985). "Prison violence: The contribution of crowding versus other determinants of prison assault rates". Journal of research in crime and delinquency. 22 (1): 41–65. doi:10.1177/0022427885022001003.

- ↑ Tootoonchi, A (1993). "College education in prisons: The inmates' perspectives". Federal Probation. 57: 34–35.

- 1 2 Jiang, S; Winfree, L (2006). "Social support, gender, and inmate adjustment to prison life insights from a national sample". The Prison Journal. 86 (1): 32–55. doi:10.1177/0032885505283876.

- 1 2 3 Comfort, M.; Grinstead, O.; McCartney, K.; Bourgois, P.; Knight, K. (2010). ""You can't do nothing in this damn place": Sex and intimacy among couples with an incarcerated male partner". The Journal of Sex Research. 1 (42): 3–12.

- ↑ Schwartzbach, M. "Privileged Information at Trial: Spousal Privileges for Same-Sex Couples". Nolo.com. Retrieved 26 September 2014.

- ↑ England, D. C. "States that Allow Conjugal Visits". Nolo.com. Retrieved 26 September 2014.

- ↑ Howser, J.; Grossman, J.; Macdonald, D. (1983). "Impact of family reunion program on institutional discipline". Journal of Offender Counseling. 8: 27–36. doi:10.1300/j264v08n01_04.

- 1 2 3 Harman, J. J.; Smith, V. E.; Egan, L. C. (2007). "The impact of incarceration on intimate relationships". Criminal Justice and Behavior. 34: 794–815. doi:10.1177/0093854807299543.

- ↑ Einhorn, L.; Williams, T.; Stanley, S.; Wunderlin, N.; Markman, H.; Eason, J. (2008). "PREP Inside and Out: Marriage Education for Inmates". Family Process. 3 (47): 341–356.

- 1 2 Lopoo, L. M.; Western, B. (2005). "Incarceration and the formation land stability of marital unions". Journal of Marriage and Family. 67: 721–734. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2005.00165.x.

- ↑ Massoglia, M.; Remster, B.; King, R. D. (2011). "Stigma or separation?: Understand the incarceration-divorce relationship". Social Forces. 90 (1): 133–155. doi:10.1093/sf/90.1.133.

- ↑ Carecedo, R. J.; Orgaz, M. B.; Frenandes-Rouco, N.; Faldowxski, R. A. (2011). "Heterosexual romantic relationships inside of prison: partner status as predictor of loneliness, sexual satisfaction, and quality of life". International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology. 55 (6): 898–924.

- 1 2 Greer, K. R. (2000). "The Changing Nature of Interpersonal Relationships in a Women's Prison". The Prison Journal. 80: 442–468. doi:10.1177/0032885500080004009.

- 1 2 Kirkham, G. L. (2000). Bisexuality in the United States: Homosexuality in Prison. Chichester, West Sussex: Columbia University Press. p. 250.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Guerino, P.; Harrison, P.; Sabol, W. "Prisoners in 2010" (PDF). http://www.bjs.gov. Bureau of Justice Statistics. Retrieved 25 September 2014. External link in

|website=(help) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 Schirmer, S.; Nellis, A.; Mauer, M. "Incarcerated parents and their children: Trends 1991-2007" (PDF). www.sentencingproject.org. The sentencing project: Research and advocacy for reform. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 [file:///C:/Users/AMCalvert/Desktop/FAQs%20About%20Children%20of%20Prisoners.p df "FAQs About Children of Prisoners"] Check

|url=value (help). Prison Fellowship. Retrieved 20 November 2016. - 1 2 3 4 5 De Masi, Ph.D., Mary E. D; Bohn, MPH, Cate Teuten (2010). "children with incarcerated parents A Journey of Children, Caregivers and Parents in New York State" (PDF). Council on Children and Families.

- ↑ Walker, E. (2011). "Risk and protective factors in mothers with a history of incarceration: Do relationships buffer the effects of trauma symptoms and substance abuse history?". Woman & Therapy. 34 (4): 359–376. doi:10.1080/02703149.2011.591662.

- ↑ Loper, A.; Carlson, L.; Levitt, L.; Scheffel, K. (1009). "Parenting stress, alliance, child contact, and adjustment of imprisoned mothers and fathers". Journal of Offender Rehabilitation. 48: 483–503. doi:10.1080/10509670903081300.

- ↑ Clarke, L.; O'Brien, M.; Godwin, H.; Hemmings, J.; Day, R.; Connolly, J.; Van Leeson, T. (2005). "Fathering behind bars in English prisons: Imprisoned fathers' identity and contact with their children". Fathering: A Journal of Theory, Research, and Practice About Men as Fathers. 3: 221–241. doi:10.3149/fth.0303.221.

- 1 2 3 Collica, K. (2010). "Surviving incarceration: Two prison-based peer programs build communities of support for female offenders". Deviant Behavior. 31 (4): 314–347. doi:10.1080/01639620903004812.

- 1 2 Poehlmann, J; Shlafer, R; Maes, E; Hanneman, A (2008). "Factors associated with young children's opportunities for maintaining family relationships during maternal incarceration". Family Relations. 57: 267–280. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3729.2008.00499.x.

- 1 2 Christian, J; Mellow, J; Thomas, S (2006). "Social and economic implications of family connections to prisoners". Journal of Criminal Justice. 34: 443–452. doi:10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2006.05.010.

- 1 2 James, G.; Harris, Y. (2013). "Children of Color and Parental Incarceration: Implications for Research, Theory, and Practice". Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development. 41 (2): 68–81. doi:10.1002/j.2161-1912.2013.00028.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Mears, D.; Cochran, J.; Siennick, S.; Bales, W. (2012). "Prison visitation and recidivism,". Justice Quarterly. 29 (6): 888–918. doi:10.1080/07418825.2011.583932.

- 1 2 3 Morenoff, J.; Harding, D. (2014). "Incarceration, prisoner reentry, and communities.". Annual Review of Sociology. 40 (1): 411–429. doi:10.1146/annurev-soc-071811-145511.

- ↑ Wilson, W. J. (1996). When work disappears: The world of the new urban poor. New York, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

- ↑ Drakulich, K. M.; Crutchfield, R. D.; Matsueda, R. L.; Rose, K. (2012). "Instability, informal control, and criminogenic situations: Community effects of returning prisoners". Crime, Law and Social Change. 57: 493–519. doi:10.1007/s10611-012-9375-0.

- ↑ Rose, D. R.; Clear, T. R. (1998). "Incarceration, social capital, and crime: Implications for social disorganization theory.". Criminology. 36 (441-480).

- ↑ Shaw, C. R.; McKaw, H. D. (1942). Juvenile delinquency and urban areas, a study of rates of delinquents in relation to differential characteristics of local communities in American cities. Chicago, Illinois: The University of Chicago Press.

- ↑ Kirk, D.S. (2009). "A natural experiment on residential change and recidivism: Lessons from Hurricane Katrina.". American Sociological Review. 74: 484–505. doi:10.1177/000312240907400308.

- 1 2 3 4 McKiernan, P.; Shamblen, S.R.; Collins, D.A.; Stradler, T.N.; Kokoski, C. (2012). "Creating lasting family connections: Reducing recidivism with community-based family strengthening model.". Criminal Justice Policy Review. 24 (1): 94–122. doi:10.1177/0887403412447505.

- ↑ Rocque, M.; Biere, D. M.; Posick, C.; MacKenzie, D. L. (2013). "Unraveling change: Social bonds and recidivism among released offenders.". Victims & Offenders. 8 (2): 209–230. doi:10.1080/15564886.2012.755141.

- ↑ Adams, K. (1992). "Adjusting to prison life.". Crime & Justice. 16.

- ↑ Bales, W.D.; Mears, D.P. (2008). "Inmate social ties and the transition to society: Does visitation reduce recidivism?". Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 45: 287–321. doi:10.1177/0022427808317574.

- 1 2 Laub, J. H.; Nagin, D. S.; Sampson, R. J. (1998). "Trajectories of change in criminal offending: Good marriages and the desistance process.". American Sociological Review. 63 (2): 225–238. doi:10.2307/2657324.

External links

- BJS - Parents in Prison and Their Minor Children

- BJS - Profile of Jail Inmates, 2002

- Children of Incarcerated Parents - Factsheet

- Lowering Recidivism Through Family Communication

- NCSL - Children of Incarcerated Parents

- Prison Reentry in Perspective