Rose Schneiderman

| Rose Schneiderman | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

April 6, 1882 Sawin, Congress Poland |

| Died |

August 11, 1972 (aged 90) New York City |

| Occupation | U.S. labor union leader |

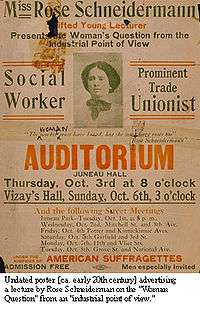

Rose Schneiderman (April 6, 1882 – August 11, 1972) was an American socialist and feminist, and one of the most prominent women labor union leaders.

As a member of the New York Women's Trade Union League (WTUL), she drew attention to unsafe workplace conditions, following the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire of 1911, and helped to pass the New York state referendum of 1917 that gave women the right to vote. Schneiderman is credited with coining the phrase "Bread and Roses", to indicate a worker’s right to something higher than subsistence living. This was later used as the title of a poem and set to music.

Early years

Rose Schneiderman was born Rachel Schneiderman on April 6, 1882,[1] the first of four children of a religious Jewish family, in the village of Sawin, 14 kilometres (9 miles) north of Chełm in Russian Poland. Her parents, Samuel and Deborah (Rothman) Schneiderman, worked in the sewing trades. Schneiderman first went to Hebrew school, normally reserved for boys, in Sawin, and then to a Russian public school in Chełm. In 1890 the family migrated to New York City's Lower East Side. Schneiderman's father died in the winter of 1892, leaving the family in poverty. Her mother worked as a seamstress, trying to keep the family together, but the financial strain forced her to put her children in a Jewish orphanage for some time. Schneiderman left school in 1895 after the sixth grade, although she would have liked to continue her education.[2] She went to work, starting as a cashier in a department store and then in 1898 as a lining stitcher in a cap factory in the Lower East Side. In 1902 she and the rest of her family moved briefly to Montreal, where she developed an interest in both radical politics and trade unionism.

Career

She returned to New York in 1903 and, with a partner worker, started organizing the women in her factory. When they applied for a charter to the United Cloth Hat and Cap Makers Union, the union told them to come back after they had succeeded in organizing twenty-five women. They did that within days and the union then chartered its first women's local.

Schneiderman obtained wider recognition during a citywide capmakers' strike in 1905. Elected secretary of her local and a delegate to the New York City Central Labor Union, she came into contact with the New York Women's Trade Union League (WTUL), an organization that lent moral and financial support to the organizing efforts of women workers. She quickly became one of the most prominent members and was elected the New York branch's vice president in 1908. She left the factory to work for the league, attending school with a stipend provided by one of the League's wealthy supporters. She was an active participant in the Uprising of the 20,000, the massive strike of shirtwaist workers in New York City led by the International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union in 1909. She also was a key member of the first International Congress of Working Women of 1919, which aimed to address women's working conditions at the First annual International Labour Organization Convention.

Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire

The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in 1911, in which 146 garment workers were burned alive or died jumping from the ninth floor of a factory building, dramatized the conditions that Schneiderman, the WTUL and the union movement were fighting. The WTUL had documented similar unsafe conditions — factories without fire escapes or that had locked the exit doors to keep workers from stealing materials — at dozens of sweatshops in New York City and surrounding communities; twenty-five workers had died in a similar sweatshop fire in Newark, New Jersey shortly before the Triangle disaster. Schneiderman expressed her anger at the memorial meeting held in the Metropolitan Opera House on April 2, 1911 to an audience largely made up of the well-heeled members of the WTUL:

"I would be a traitor to these poor burned bodies if I came here to talk good fellowship. We have tried you good people of the public and we have found you wanting. The old Inquisition had its rack and its thumbscrews and its instruments of torture with iron teeth. We know what these things are today; the iron teeth are our necessities, the thumbscrews are the high-powered and swift machinery close to which we must work, and the rack is here in the firetrap structures that will destroy us the minute they catch on fire.

This is not the first time girls have been burned alive in the city. Every week I must learn of the untimely death of one of my sister workers. Every year thousands of us are maimed. The life of men and women is so cheap and property is so sacred. There are so many of us for one job it matters little if 146 of us are burned to death.

We have tried you citizens; we are trying you now, and you have a couple of dollars for the sorrowing mothers, brothers and sisters by way of a charity gift. But every time the workers come out in the only way they know to protest against conditions which are unbearable the strong hand of the law is allowed to press down heavily upon us.

Public officials have only words of warning to us – warning that we must be intensely peaceable, and they have the workhouse just back of all their warnings. The strong hand of the law beats us back, when we rise, into the conditions that make life unbearable.

I can't talk fellowship to you who are gathered here. Too much blood has been spilled. I know from my experience it is up to the working people to save themselves. The only way they can save themselves is by a strong working-class movement."— Rose Schneiderman[3]

Despite her harsh words, Schneiderman continued working in the WTUL as an organizer, returning to it after a frustrating year on the staff of the male-dominated ILGWU. She subsequently became president of its New York branch, then its national president for more than twenty years until it disbanded in 1950.

In 1920, Schneiderman ran for the United States Senate as the candidate of the New York State Labor Party, receiving 15,086 votes and finishing behind Prohibitionist Ella A. Boole (159,623 votes) and Socialist Jacob Panken, (151,246).[4] Her platform had called for the construction of nonprofit housing for workers, improved neighborhood schools, publicly owned power utilities and staple food markets, and state-funded health and unemployment insurance for all Americans.

Schneiderman was a founding member of the American Civil Liberties Union, and became friends with Eleanor Roosevelt and her husband, Franklin D. Roosevelt. In 1926, she was elected president of the National WTUL, a post she retained until her retirement. In 1933, she was the only woman to be appointed on the National Recovery Administration's Labor Advisory Board by President Roosevelt, and was a member of Roosevelt's "brain trust" during that decade. From 1937 to 1944 she was secretary of labor for New York State, and campaigned for the extension of social security to domestic workers and for equal pay for female workers. During the late 1930s and early 1940s, she was involved in efforts to rescue European Jews, but could only rescue a small number. Albert Einstein wrote her: “It must be a source of deep gratification to you to be making so important a contribution to rescuing our persecuted fellow Jews from their calamitous peril and leading them toward a better future.”[5]

Women's suffrage

Schneiderman was an active feminist, campaigning for women's suffrage as a member of the National American Woman Suffrage Association. She saw suffrage as part and parcel of her fight for economic rights. When a state legislator warned in 1912 that "Get women into the arena of politics with its alliances and distressing contests--the delicacy is gone, the charm is gone, and you emasculize women", Schneiderman replied:

"We have women working in the foundries, stripped to the waist, if you please, because of the heat. Yet the Senator says nothing about these women losing their charm. They have got to retain their charm and delicacy and work in foundries. Of course, you know the reason they are employed in foundries is that they are cheaper and work longer hours than men. Women in the laundries, for instance, stand for 13 or 14 hours in the terrible steam and heat with their hands in hot starch. Surely these women won't lose any more of their beauty and charm by putting a ballot in a ballot box once a year than they are likely to lose standing in foundries or laundries all year round. There is no harder contest than the contest for bread, let me tell you that"— Rose Schneiderman[6]

Schneiderman helped pass the New York state referendum in 1917 that gave women the right to vote. On the other hand, she opposed passage of the Equal Rights Amendment to the United States Constitution proposed by the National Woman's Party on the ground that it would deprive working women of the special statutory protections for which the WTUL had fought so hard.

Legacy

Schneiderman is also credited with coining one of the most memorable phrases of the women's movement and the labor movement of her era:

"What the woman who labors wants is the right to live, not simply exist — the right to life as the rich woman has the right to life, and the sun and music and art. You have nothing that the humblest worker has not a right to have also. The worker must have bread, but she must have roses, too. Help, you women of privilege, give her the ballot to fight with."— Rose Schneiderman, 1912[7]

Her phrase "Bread and Roses", became associated with a 1912 textile strike of largely immigrant, largely women workers in Lawrence, Massachusetts.It was later used as the title of a poem and was set to music by Mimi Fariña and sung by various artists, among them Judy Collins and John Denver.[8]

In 1949, Schneiderman retired from public life, making occasional radio speeches and appearances for various labor unions, devoting her time to writing her memoirs, which she published under the title All for One, in 1967.

Schneiderman never married, and treated her nieces and nephews as if they were her own children.[9] She had a long-term relationship with Maud O'Farrell Swartz (1879-1937), another working class woman active in the WTUL, until Swartz' death in 1937. Rose Schneiderman died in New York City on August 11, 1972, at age ninety.

In March 2011, almost 100 years to the day after the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, Maine's Republican Governor Paul LePage, who was inaugurated in January of the same year, has had a three-year-old 36 foot-wide mural with scenes of Maine workers on the Department of Labor's building in Augusta removed and brought to a secret location.[9] The mural has 11 panels, and has also a picture showing Rose Schneiderman, although she had never lived or worked in Maine.[10] According to the New York Times, "LePage has also ordered that the Labor Department’s seven conference rooms be renamed. One is named after César Chávez, the farmworkers’ leader; one after Rose Schneiderman, a leader of the New York Women’s Trade Union League a century ago; and one after Frances Perkins, who became the nation’s first female labor secretary and is buried in Maine."[11]

On April 1, 2011 it was disclosed that a federal lawsuit had been filed in U.S. District Court seeking "to confirm the mural's current location, insure that the artwork is adequately preserved, and ultimately to restore it to the Department of Labor's lobby in Augusta".[12] On March 23, 2012, U.S. District Judge John A. Woodcock ruled that the removal of the mural was a protected form of government speech and that LePage removing it would be no different from his refusing to read aloud a history of labor in Maine.[13] A month later, supporters of the mural filed a notice of appeal in the First Circuit Court of Appeals in Boston.[14] The Court rejected the appeal on November 28, 2012.[15] On January 13, 2013, it was announced that the mural had been placed in the Maine State Museum's atrium per an agreement between the Museum and the Department of Labor, and that it would be available for public viewing the next day.[16]

Notes

- ↑ Listed as 1884 or 1886 in some sources.

- ↑ Schrom Dye, Nancy, Rose Schneiderman, Papers of the Women's Trade Union League and Its Principal Leaders, Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe College, Research Publications, 1981

- ↑ Stein, Leon (ed), Out of the Sweatshop. The Struggle for Industrial Democracy, New York: Quadrangle/New Times Book Company, 1977, pp. 196-197

- ↑ Willis Fletcher Johnson; Roscoe Conkling Ensign Brown, Walter Whipple Spooner, Willis Holly (1922). History of the State of New York, Political and Governmental. The Syracuse Press. pp. 347–348, 350. Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthors=(help) - ↑ Orleck, Annalise, Rose Schneiderman 1882 – 1972, Jewish Women: A Comprehensive Historical Encyclopedia, 20 March 2009. Jewish Women's Archive

- ↑ Document 19: Miss Rose Schneiderman, Cap Maker, Replies to New York Senator on Delicacy and Charm of Women, New York: Wage Earners' Suffrage League, 1912; microfilm, History of Women, reel 951, #9222

- ↑ Eisenstein, Sarah, Give us bread but give us roses. Working women's consciousness in the United States, 1890 to the First World War, Routledge, London 1983, p. 32, ISBN 0-7100-9479-5

- ↑ Morris, David, When Unions are Strong, Americans Enjoy the Fruits of Their Labor, The Huffington Post, April 8, 2011

- 1 2 Efrem, Maia, An Aunt’s Legacy Is Erased in Maine. A Century After Triangle Fire, Labor Activist’s Name Is Purged, The Jewish Daily Forward, April 27, 2011

- ↑ Mural of Maine's Workers, The New York Times, March 23, 2011

- ↑ Greenhouse, Steven, Mural of Maine’s Workers Becomes Political Target, The New York Times, March 23, 2011

- ↑ "Fed. lawsuit filed over Maine labor mural removal". Boston Globe. April 1, 2011.

- ↑ "Judge sides with LePage on mural removal". Kennebec Journal. March 24, 2012. Retrieved July 12, 2012.

- ↑ "Labor mural plaintiffs file notice of appeal". Kennebec Journal. April 24, 2012. Retrieved July 12, 2012.

- ↑ "1st Circuit rejects Maine labor mural appeal". Bangor Daily News. November 28, 2012. Retrieved November 28, 2012.

- ↑ "Labor mural LePage had removed to get new home at Maine State Museum". Bangor Daily News. January 13, 2013. Retrieved January 14, 2013.

Further reading

- Banks Nutter, Kathleen, Rose Schneiderman, in American National Biography, vol. 19, ed. John A. Garraty and Mark C. Carnes, New York: Oxford University Press, 1999, p. 407-08

- Endelman, Gary E., Solidarity Forever: Rose Schneiderman & the Women's Trade Union League, Beaufort Books 1981

- Foner, Philip S., Women and the American Labor Movement. From the First Trade Unions to the Present, The Free Press, New York 1979-1980

- Kessler-Harris, Alice, Rose Schneiderman and the Limits of Women’s Trade Unionism, in Labor Leaders in America, Melvyn Dubofsky and Warren Van Tine (eds.), Urbana: University of Illinois Press 1987

- McGuire, John Thomas, From Socialism to Social Justice Feminism: Rose Schneiderman and the Quest for Urban Equity, 1911-1933, Journal of Urban History 35(7) 2009, p. 998–1019

- Orleck, Annalise, Common Sense and a Little Fire: Women and Working-Class Politics in the United States, 1900-1965, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press 1995

- Schneiderman, Rose, All for one, New York, P. S. Eriksson 1967

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rose Schneiderman. |

- Biography and relationship with Eleanor Roosevelt

- A capmaker's story

- Guide to the Rose Schneiderman archive of papers (1909-1964) at the Tamiment Library, New York City

- Guide to the Rose Schneiderman collection of photographic prints (1909-1962) at the Tamiment Library, New York City