Scottish island names

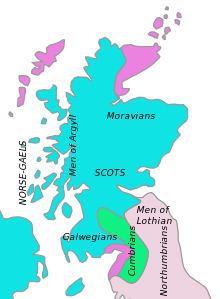

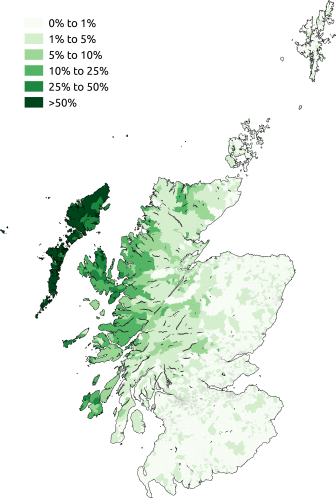

The modern names of Scottish islands stem from two main influences. There are a large number of names that derive from the Scottish Gaelic language in the Hebrides and Firth of Clyde. In the Northern Isles most place names have a Norse origin. There are also some island place names that originate from three other influences, including a limited number that are essentially English language names, a few that are of Brittonic origin and some of an unknown origin that may represent a pre-Celtic language. These islands have all been occupied by the speakers of at least three and in many cases four or more languages since the Iron Age, and many of the names of these islands have more than one possible meaning as a result.[Note 1]

Scotland has over 790 offshore islands, most of which are to be found in four main groups: Shetland, Orkney, and the Hebrides, sub-divided into the Inner Hebrides and Outer Hebrides. There are also clusters of islands in the Firth of Clyde, Firth of Forth, and Solway Firth, and numerous small islands within the many bodies of fresh water in Scotland including Loch Lomond and Loch Maree.

Main languages

Early languages

As humans have lived on the islands of Scotland since at least Mesolithic times, it is clear that pre-modern languages must have been used, and by extension names for the islands, that have been lost to history. Proto-Celtic is the presumed ancestor language of all the known Celtic languages. Proponents of the controversial Vasconic substratum theory suggest that many western European languages contain remnants of an even older language family of Vasconic languages, of which Basque is the only surviving member. This proposal was originally made by the German linguist Theo Vennemann, but has been rejected by other linguists.

A small number of island names may contain elements of such an early Celtic or pre-Celtic language, but no certain knowledge of any pre-Pictish language exists anywhere in Scotland.[2]

Celtic languages

British or Brythonic was an ancient P-Celtic language spoken in Britain. It is a form of Insular Celtic, which is descended from Proto-Celtic, the hypothetical parent language that many linguistics belief had already begun to diverge into separate dialects or languages in the first half of the first millennium BC.[3][4][5][6] By the sixth century AD, scholars of early Insular history often begin to talk about four geographically separate forms of British: Welsh, Breton, Cornish, and the now extinct Cumbric language. These are collectively known as the Brythonic languages. It is clear that whenever place names are recorded at an early date as having been transposed from a form of P-Celtic into Gaelic that this occurred prior to the transformation from "Old British" into modern Welsh.[7] There are numerous Scottish place names with Brythonic roots although the number of island names involved is relatively small.

The Pictish language offers considerable difficulties. It is a term used for the language(s) thought to have been spoken by the Picts, the people of northern and central Scotland in the Early Middle Ages. It may have been a fifth branch of Brythonic; Kenneth H. Jackson thought that the evidence is weak,[8] but Katherine Forsyth disagreed with his argument.[9] The idea that a distinct Pictish language was perceived at some point is attested clearly in Bede's early 8th-century Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum, which names it as distinct from both Old Welsh and Old Gaelic.[10] However, there is virtually no direct attestation of Pictish short of the names of people found on monuments in the lands controlled by the Picts - the area north of the Forth-Clyde line in the Early Middle Ages.[11] Many of these monuments include elaborate carved symbols, but an understanding of their significance has so far proved as elusive as interpretation of the few written fragments, which have been described as resembling an "odd sort of gibberish".[12] Nonetheless, there is significant indirect place-name evidence for the Picts use of Brythonic or P-Celtic.[11] The term "Pritennic" is sometimes used to refer to the proto-Pictish language spoken in this area during the Iron Age.

Given the paucity of knowledge about the Pictish language it may be assumed that islands names with P-Celtic affiliations in the southern Hebrides, and Firths of Clyde and Forth are Brythonic and those to the north and west are of Pictish origin.

This Goidelic language arrived via Ireland due to the growing influence of the kingdom of Dalriada from the 6th century onwards.[13] It is still spoken in parts of the Scottish Highlands and the Hebrides, and in Scottish cities by some communities. It was formerly spoken over a far wider area than today, even in the recent past. Scottish Gaelic, along with modern Manx and Irish, are descended from Middle Irish, a derivative of Old Irish, which is descended in turn from Primitive Irish. This the oldest known form of the Goidelic languages, which is known only from fragments, mostly personal names, inscribed on stone in the Ogham alphabet in Ireland and western Britain up to about the 6th century. The Beurla-reagaird is a Gaelic-based cant of the Scottish travelling community.[14]

Norse and Norn

Old Norse is a North Germanic language that was spoken by inhabitants of Scandinavia and of their overseas settlements during the Viking Age, until about 1300. Its influence on Scots island names is considerable due to the development of both the Earldom of Orkney and the Kingdom of the Isles which resulted in almost all of the inhabitable islands of Scotland (except those in the Firth of Forth) coming under Norse control from the 9th to 13th centuries.

Norn is an extinct North Germanic language that developed from Old Norse and was spoken in Shetland, Orkney and possibly Caithness. Together with Faroese, Icelandic and modern Norwegian it belongs to the West Scandinavian group. Very little written evidence of the language has survived and as a result it is not possible to distinguish any island names that may be Norn rather than Old Norse. After the Northern Isles were pledged to Scotland by Norway in the 15th century, the early Scottish Earls spoke Gaelic when the majority of their subjects spoke Norn and both of these languages were then replaced by Insular Scots.[17]

English and Scots

English is a West Germanic language, the modern variant of which is generally dated from about 1550. The related Scots language, sometimes regarded as a variety of English, is has regional and historic importance in Scotland. It is officially recognised as autochthonous language under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages.[18] It is a language variety historically spoken in Lowland Scotland and parts of Ulster.

English is a West Germanic language, the modern variant of which is generally dated from about 1550. Although they are the dominant languages in modern Scotland the presence of both Scots and English in island names is limited

Pre-Celtic remnants

There are three island names in Shetland of unknown and possibly pre-Celtic origin: Fetlar, Unst and Yell. The earliest recorded forms of these three names do carry Norse meanings: Fetlar is the plural of fetill and means "shoulder-straps" Omstr is "corn-stack" and í Ála is from ál meaning "deep furrow". However these descriptions are hardly obvious ones as island names and are probably adaptations of a pre-Norse language.[19][20] This may have been Pictish but there is no clear evidence for this.[21][22]

The roots of several of the Hebrides may also have a pre-Celtic origin. Indeed, the name comes from Ebudae recorded by Ptolemy, via the mis-reading "Hebudes" and may itself have a pre-Celtic root.[23]

- Mull was recorded by Ptolemy as Malaios[24] possibly meaning "lofty isle"[23] although it is pre-Gaelic in origin.[25] In Norse times it became Mýl.[26]

- The 7th century abbot of Iona Adomnán records Coll as Colosus and Tiree as Ethica, which may be pre-Celtic names.[27]

- Islay is Ptolemy's Epidion,[24] the use of the "p" hinting at a Brythonic or Pictish tribal name.[28] Adomnán refers to the island as Ilea[27] and occurs in early Irish records as Ile and as Il in Old Norse. The root is not Gaelic and of unknown origin.[26]

- The etymology of Skye is complex and may also include a pre-Celtic root.[26]

- Lewis is Ljoðhús in Old Norse and although various suggestions have been made as to a Norse meaning (such as "song house") the name is not of Gaelic origin and the Norse credentials are questionable.[26][29]

- The origin of Uist (OldNorse: Ívist) is similarly unclear.[26]

- Rùm may be from the Old Norse rõm-øy for "wide island" or Gaelic ì-dhruim meaning "isle of the ridge"[30] although Mac an Tàilleir (2003) is unequivocal that it is a "pre-Gaelic name and unclear".[29][31]

- Seil is probably a pre-Gaelic name,[32] although a case has been made for a Norse derivation.[33]

- The etymology of Arran is also obscure. Haswell-Smith (2004) offers a Brythonic derivation and a meaning of "high place".[34] The Acallam na Senórach describes Arran as being "between Alba and Cruithen-land" although there is possible confusion in the annals between the meaning of Cruithen to refer to the Picts, the Cruithnigh of Ireland and the Welsh equivalent of Prydain to refer to Britain as a whole.[35] In support of the Vasconic substratum hypothesis, Vennemann notes the recurrence of the element aran, (Unified Basque haran) meaning"valley", in names like Val d'Aran, Arundel, or Arendal.[36] In early Irish literature Arran is "Aru"[37] and Watson (1926) notes there are similar names in Wales but suggests it may be pre-Celtic.[38]

Brythonic & Pictish names

Several of the islands of the Clyde have possible Brythonic roots. In addition to Arran (see above) Bute may have a British root and Great and Little Cumbrae both certainly have (see below).

Inchkeith in the Firth of Forth is recorded as "Insula Keth" in the 12th century Life of Saint Serf. The name may derive from Innis Cheith or Innis Coit and both Mac an Tàilleir (2003) and Watson (1926) suggest that the root is the Brthyonic coed. The derivation would appear to be assumed rather than attested and the modern form is Innis Cheith.[39][40] Caer in Welsh means a "stone-girt fort" and was especially applied to Roman camp sites. This is the root of Cramond Island in the Forth, with Caramond meaning "the fort on the Almond river".[41] The island of Threave on the River Dee in Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland takes its name from P-Celtic tref, meaning "homestead".[42]

It is assumed that Pictish names must once have predominated in the northern Inner Hebrides, Outer Hebrides, Orkney and Shetland although the historical record is sparse. For example, Hunter (2000) states that in relation to King Bridei I of the Picts in the sixth century: "As for Shetland, Orkney, Skye and the Western Isles, their inhabitants, most of whom appear to have been Pictish in culture and speech at this time, are likely to have regarded Bridei as a fairly distant presence.”[43][44] However, the place names that existed prior to the 9th century have been all but obliterated by the incoming Norse-speaking Gall-Ghaeils.[45]

Orkney is pre-Norse in origin and Pictish, as may be the uninhabited Orkney island name Damsay, meaning "lady's isle".[46] Remarkably few Pictish placenames of any kind can be identified in Orkney and Shetland, although some apparently Norse names may be adaptations of earlier Pictish ones.[47][48] There are various ogham inscriptions such as on the Lunnasting stone found in Shetland that have been claimed as representing Pictish, or perhaps even a precursor language.

In the 14th century John of Fordun also records the name of Inchcolm as "Eumonia" (referring to the monasterium Sancti Columbe in insula Euomonia) a name of likely Brythonic origin.[49]

Norse names

From some point before 900 until the 14th century both Shetland and Orkney became Norse societies.[50] The Norse also dominated the Hebrides and the islands of the Clyde for much of the same period, although their influence was much weaker there from the 13th century onwards. According to Ó Corráin (1998) "when and how the Vikings conquered and occupied the Isles is unknown, perhaps unknowable"[51] although from 793 onwards repeated raids by Vikings on the British Isles are recorded. "All the islands of Britain" were devastated in 794[52] with Iona being sacked in 802 and 806.[53]

As a result, most of the island names in Orkney and Shetland have Norse names and many in the Hebrides are Gaelic transformations of the original Norse, with the Norse ending -øy or -ey for "island" becoming -aigh in Gaelic and then -ay in modern Scots/English.

Gaelic influence

Perhaps surprisingly Shetland may have a Gaelic root—the name is Innse Chat is referred to in early Irish literature and it is just possible that this forms part of the later Norn name Hjaltland[46][54]— but the influence of this language in the toponymy of the Northern Isles is slight. No Gaelic-derived island names and indeed only two Q-Celtic words exist in the language of modern Orcadians - "iper" from eabhar, meaning a midden slurry, and "keero" from caora - used to describe a small sheep in the North Isles.[55]

The Hebrides remain the stronghold of the modern Gàidhealtachd and unsurprisingly this language has had a significant influence on the islands there. It has been argued that the Norse impact on the onomasticon only applied to the islands north of Ardnamurchan and that original Gaelic place names predominate to the south.[45] However, recent research suggests that the obliteration of pre-Norse names throughout the Hebrides was almost total and Gaelic derived place names on the southern islands are of post-Norse origin.[56][57]

There are also examples of island names that were originally Gaelic but have become completely replaced. For example, Adomnán records Sainea, Elena, Ommon and Oideacha in the Inner Hebrides, which are of unknown location and these names must have passed out of usage in the Norse era.[58] One of the complexities is that an island such as Rona may have had a Celtic name, that was replaced by a similar-sounding Norse name, but then reverted to an essentially Gaelic name with a Norse ending.[59]

Scots and English names

In the context of the Northern Isles it should be borne in mind that Old Norse is a dead language and that as a result names of Old Norse origin exist only as loan words in the Scots language.[54] Nonetheless if we distinguish between names of obviously Norse origin and those with a significant Scots element the great majority are in the former camp. "Muckle", meaning large or big, is one of few Scots words in the island names of the Nordreyar and appears in Muckle Roe and Muckle Flugga in Shetland and Muckle Green Holm and Muckle Skerry in Orkney.

Many small islets and skerries have Scots or Insular Scots names such as Da Skerries o da Rokness and Da Buddle Stane in Shetland, and Kirk Rocks in Orkney.

Great Cumbrae and Little Cumbrae are English/Brythonic in derivation and there are other examples of the use of "great" and "little" such as Great Bernera and Rysa Little which are English/Gaelic and Norse/English respectively. The informal use of "Isle of" is commonplace, although only the Isle of Ewe, the Isle of May and Isle Martin of the larger Scottish islands use this nomenclature in a formal sense.[60] "Island" also occurs, as in Island Macaskin and Mealista Island although both islands are also known by their Gaelic names of Eilean Macaskin and Eilean Mhealasta. Holy Island off Arran is an entirely English name as is the collective Small Isles. Ailsa Craig is also known as "Paddy's Milestone".[61] Big Scare in the Solway Firth is an English/Norse combination, the second word coming from sker, a skerry.

Some smaller islets and skerries have English names such as Barrel of Butter and the Old Man of Hoy in Orkney and Maiden Island and Bottle Island in the Inner Hebrides.

The Norse often gave animal names to islands and these have been transferred into English in for example, the Calf of Flotta and Horse of Copinsay. Brother Isle is an anglicisation of breiðare-øy meaning "broad beach island". The Norse holmr, meaning "a small and rounded islet" has become "Holm" in English and there are numerous examples of this use including Corn Holm, Thieves Holm and Little Holm.

Summary of inhabited islands

Etymological details for all inhabited islands and some larger uninhabited ones are provided at Hebrides, Northern Isles, Islands of the Clyde and Islands of the Forth.

Based on these tables, for the inhabited off-shore islands of Scotland (and counting Lewis and Harris as two islands for this purpose) the following results apply, excluding Scots/English qualifiers such as "muckle" "east", "little" etc.

| Archipelago | Pre-Celtic | Old Norse | Scots Gaelic | Scots/English | Other | Notes | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shetland | 3 | 12 | 1 | 0 | 0 | There are two islands with names of joint Norse/Celtic origin, Papa Stour and the Shetland Mainland. | 16 |

| Orkney | 0 | 20 | 0 | 1 | 1 | Shapinsay is of unknown derivation, the Orkney mainland itself is probably Pictish in origin. South Walls is a Scots name based in part on a Norse root. | 22 |

| Outer Hebrides | 5 | 7 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 16 | |

| Inner Hebrides | 8 | 17 | 12 | 0 | 1 | The derivation of Easdale is not clear. | 38 |

| Islands of the Clyde | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | Bute is of uncertain origin and could be Norse, Gaelic or Brythonic. Arran probably has, and Great Cumbrae does have, a Brythonic root. | 6 |

| Islands of the Forth | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Totals | 16 | 57 | 19 | 2 | 5 | 99 |

See also

- Languages of Scotland

- Etymology of Arran

- Etymology of Gigha

- Origin of names of St Kilda

- List of Scottish Gaelic place names

- Goidelic substrate hypothesis

- Insular Celtic languages

References

- Notes

- ↑ Writing in the 1880s, Rev. Thomas McLauchlan urged caution, noting that it "is necessary to ensure a historical, and hence an accurate instead of a fanciful, account of our topographical terms. Any one acquainted with Highland etymologies, knows to what an extent our imaginative countrymen have gone in attaching meanings altogether fanciful to such terms; but nothing is more likely to mislead the inquirer than elevating our ancient and irregular orthography to a position which it is altogether unfit to occupy".[1]

- Footnotes

- ↑ M'Lauchlan, Rev. Thomas (Jan 1866) "On the Kymric Element in the Celtic Topography of Scotland". Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. Edinburgh, VI Part 2, p. 318

- ↑ Clarkson (2008) pp. 30-34

- ↑ Henderson, Jon C. (2007). The Atlantic Iron Age: Settlement and Identity in the First Millennium BC. Routledge. pp. 292–95.

- ↑ Sims-Williams, Patrick (2007). Studies on Celtic Languages before the Year 1000. CMCS. p. 1.

- ↑ Koch, John (2006). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 1455.

- ↑ Eska, Joseph (2008). "Continental Celtic". In Roger Woodard. The Ancient Languages of Europe. Cambridge.

- ↑ Watson (1994) p. 71

- ↑ Jackson, Kenneth (1955). "The Pictish Language". In F. T. Wainwright. The Problem of the Picts. Edinburgh: Nelson. pp. 129–66.

- ↑ Forsyth, Katherine (1997). Language in Pictland: the case against 'non-Indo-European Pictish' (PDF). Utrecht: Stichting Uitgeverij de Keltische Draak. ISBN 90-802785-5-6. Retrieved 4 June 2015.

- ↑ Bede (731) Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum.

- 1 2 Clarkson (2008) p. 31

- ↑ Clarkson (2008) p. 10

- ↑ Armit, Ian "The Iron Age" in Omand (2006) p. 57 - but see Campbell critique

- ↑ Neat, Timothy (2002) The Summer Walkers. Edinburgh. Birlinn. pp. 225-29

- ↑ Grant, William (1931) Scottish National Dictionary

- ↑ Gregg R.J. (1972) The Scotch-Irish Dialect Boundaries in Ulster in Wakelin M.F., Patterns in the Folk Speech of The British Isles, London

- ↑ Lamb, Gregor "The Orkney Tongue" in Omand (2003) pp. 248-49.

- ↑ "European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages" Scottish Government. Retrieved 27 September 2007.

- ↑ Gammeltoft (2010) p. 17

- ↑ Gammeltoft (2010) pp. 19-20

- ↑ Gammeltoft (2010) p. 9

- ↑ "Norn" Shetlopedia. Retrieved 23 Jan 2011.

- 1 2 Watson (1994) p. 38

- 1 2 Watson (1994) p. 37

- ↑ Mac an Tàilleir (2003) p. 89

- 1 2 3 4 5 Gammeltoft, Peder "Scandinavian Naming-Systems in the Hebrides—A Way of Understanding how the Scandinavians were in Contact with Gaels and Picts?" in Ballin Smith et al (2007) p. 487

- 1 2 Watson (1994) pp. 84-86

- ↑ Watson (1994) p. 45

- 1 2 Mac an Tàilleir (2003)

- ↑ Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 138

- ↑ Watson (1994) p. 95

- ↑ Mac an Tàilleir (2003) p. 104

- ↑ Rae (2011) p. 9

- ↑ Haswell-Smith 2004 p. 11

- ↑ Watson (1994) p. 67

- ↑ Baldi & Page (December 2006) Review of "Europa Vasconica - Europa Semitica", Lingua, 116 Issue 12 pp. 2183-2220

- ↑ Watson (1994) p. 64

- ↑ Watson (1994) p. 97

- ↑ Watson (1994) pp. 381-82

- ↑ "The Life of Saint Serf" cyberscotia.com. Retrieved 27 Dec 2010.

- ↑ Watson (1994) pp. 365, 369

- ↑ Watson (1994) p. 358

- ↑ Hunter (2000) pp. 44, 49

- ↑ Watson (1994) p. 65

- 1 2 Woolf, Alex "The Age of the Sea-Kings: 900-1300" in Omand (2006) p. 95

- 1 2 Gammeltoft (2010) p. 21

- ↑ Gammeltoft (2010) pp. 8-9

- ↑ Sandnes (2010) p. 8

- ↑ Watson (1994) p. 104

- ↑ Sandnes (2003) p 14

- ↑ Ó Corráin (1998) p. 25

- ↑ Thomson (2008) p. 24-27

- ↑ Woolf (2007) p. 57

- 1 2 Sandnes (2010) p. 9

- ↑ Lamb, Gregor "The Orkney Tongue" in Omand (2003) p. 250.

- ↑ Jennings and Kruse (2009) pp. 83–84

- ↑ King and Cotter (2012) p. 4

- ↑ Watson (1994) p. 93

- ↑ Gammeltoft (2010) pp. 482, 486

- ↑ Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 515

- ↑ Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 4

- General references

- Ballin Smith, B. and Banks, I. (eds) (2002) In the Shadow of the Brochs, the Iron Age in Scotland. Stroud. Tempus. ISBN 0-7524-2517-X

- Ballin Smith, Beverley; Taylor, Simon; and Williams, Gareth (2007) West over Sea: Studies in Scandinavian Sea-Borne Expansion and Settlement Before 1300. Leiden. Brill. ISBN 97890-04-15893-1

- Clarkson, Tim (2008) The Picts: A History. Stroud. The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-4392-8

- Haswell-Smith, Hamish (2004). The Scottish Islands. Edinburgh: Canongate. ISBN 978-1-84195-454-7.

- Hunter, James (2000) Last of the Free: A History of the Highlands and Islands of Scotland. Edinburgh. Mainstream. ISBN 1-84018-376-4

- Gammeltoft, Peder (2010) "Shetland and Orkney Island-Names – A Dynamic Group". Northern Lights, Northern Words. Selected Papers from the FRLSU Conference, Kirkwall 2009, edited by Robert McColl Millar.

- Jennings, Andrew and Kruse, Arne "One Coast-Three Peoples: Names and Ethnicity in the Scottish West during the Early Viking period" in Woolf, Alex (ed.) (2009) Scandinavian Scotland – Twenty Years After. St Andrews. St Andrews University Press. ISBN 978-0-9512573-7-1

- King, Jacob and Cotter, Michelle (2012) Place-names in Islay and Jura. Perth. Scottish Natural Heritage.

- Iain Mac an Tàilleir (2003). "Placenames" (pdf). Pàrlamaid na h-Alba. Retrieved 23 July 2007.

- Murray, W. H. (1966) The Hebrides. London. Heinemann.

- Murray, W.H. (1973) The Islands of Western Scotland. London. Eyre Methuen. SBN 413303802

- Omand, Donald (ed.) (2003) The Orkney Book. Edinburgh. Birlinn. ISBN 1-84158-254-9

- Omand, Donald (ed.) (2006) The Argyll Book. Edinburgh. Birlinn. ISBN 1-84158-480-0

- Rae, Robert J. "A Voyage in Search of Hinba" in Historic Argyll (2011) No. 16. Lorn Archaeological and Historical Society. Edited by J Overnell.

- Sandnes, Berit (2003) From Starafjall to Starling Hill: An investigation of the formation and development of Old Norse place-names in Orkney. (pdf) Doctoral Dissertation, NTU Trondheim.

- Sandnes, Berit (2010) "Linguistic patterns in the place-names of Norway and the Northern Isles" Northern Lights, Northern Words. Selected Papers from the FRLSU Conference, Kirkwall 2009, edited by Robert McColl Millar.

- Thompson, Francis (1968) Harris and Lewis, Outer Hebrides. Newton Abbot. David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-4260-6

- Watson, W. J. (2004) The Celtic Place-Names of Scotland. Edinburgh. Birlinn. ISBN 1-84158-323-5. First published 1926.