Second Battle of Naktong Bulge

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

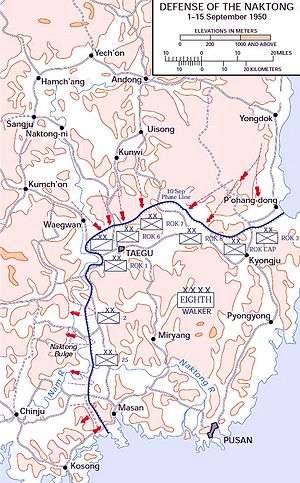

The Second Battle of Naktong Bulge was an engagement between United Nations (UN) and North Korean (NK) forces early in the Korean War from September 1 to September 15, 1950, along the Naktong River in South Korea. It was a part of the Battle of Pusan Perimeter, and was one of several large engagements fought simultaneously. The battle ended in a victory for the United Nations after large numbers of United States (US) and Republic of Korea (ROK) troops repelled a strong North Korean attack.

After the First Battle of Naktong Bulge, the US Army's 2nd Infantry Division was moved to defend the Naktong River line. The division, which was untried in combat, was struck with a strong attack by several divisions of the Korean People's Army which crossed the river and struck all along the division's line. The force of the attack split the US 2nd Infantry Division in half, and the North Koreans were able to penetrate to Yongsan, promoting a fight there.

The urgency of the threat to Pusan Perimeter prompted the US Marine Corps 1st Provisional Marine Brigade to be brought in to reinforce the US Army troops. In two weeks of heavy fighting, the US forces were able to force the North Koreans out of the Naktong Bulge region. The North Koreans were further repulsed after the UN counterattack at Inchon, which culminated in the virtual destruction of the North Korean army.

Background

Pusan Perimeter

From the outbreak of the Korean War and the invasion of South Korea by the North, the North Korean People's Army had enjoyed superiority in both manpower and equipment over both the Republic of Korea Army and the United Nations forces dispatched to South Korea to prevent it from collapsing.[1] The North Korean strategy was to aggressively pursue UN and ROK forces on all avenues of approach south and to engage them aggressively, attacking from the front and initiating a double envelopment of both flanks of the unit, which allowed the North Koreans to surround and cut off the opposing force, which would then be forced to retreat in disarray, often leaving behind much of its equipment.[2] From their initial June 25 offensive to fights in July and early August, the North Koreans used this strategy to effectively defeat any UN force and push it south.[3] However, when the UN forces, under the Eighth United States Army, established the Pusan Perimeter in August, the UN troops held a continuous line along the peninsula which North Korean troops could not flank, and their advantages in numbers decreased daily as the superior UN logistical system brought in more troops and supplies to the UN army.[4]

When the North Koreans approached the Pusan Perimeter on August 5, they attempted the same frontal assault technique on the four main avenues of approach into the perimeter. Throughout August, the NK 6th Division, and later the NK 7th Division engaged the US 25th Infantry Division at the Battle of Masan, initially repelling a UN counteroffensive before countering with battles at Komam-ni[5] and Battle Mountain.[6] These attacks stalled as UN forces, well equipped and with plenty of reserves, repeatedly repelled North Korean attacks.[7] North of Masan, the NK 4th Division and the US 24th Infantry Division sparred in the Naktong Bulge area. In the First Battle of Naktong Bulge, the North Korean division was unable to hold its bridgehead across the river as large numbers of US reserve forces were brought in to repel it, and on August 19, the NK 4th Division was forced back across the river with 50 percent casualties.[8][9] In the Taegu region, five North Korean divisions were repulsed by three UN divisions in several attempts to attack the city during the Battle of Taegu.[10][11] Particularly heavy fighting took place at the Battle of the Bowling Alley where the NK 13th Division was almost completely destroyed in the attack.[12] On the east coast, three more North Korean divisions were repulsed by the South Koreans at P'ohang-dong during the Battle of P'ohang-dong.[13] All along the front, the North Korean troops were reeling from these defeats, the first time in the war their strategies were not working.[14]

September push

In planning its new offensive, the North Korean command decided any attempt to flank the UN force was impossible thanks to the support of the UN navy.[12] Instead, they opted to use frontal attack to breach the perimeter and collapse it as the only hope of achieving success in the battle.[4] Fed by intelligence from the Soviet Union the North Koreans were aware the UN forces were building up along the Pusan Perimeter and that it must conduct an offensive soon or it could not win the battle.[15] A secondary objective was to surround Taegu and destroy the UN and ROK units in that city. As part of this mission, the North Korean units would first cut the supply lines to Taegu.[16][17]

On August 20, the North Korean commands distributed operations orders to their subordinate units.[15] The North Koreans called for a simultaneous five-prong attack against the UN lines. These attacks would overwhelm the UN defenders and allow the North Koreans to break through the lines in at least one place to force the UN forces back. Five battle groupings were ordered.[18] The center attack called for the NK 9th Division, NK 4th Division, NK 2nd Division, and NK 10th Division break through the US 2nd Infantry Division at the Naktong Bulge to Miryang and Yongsan.[19]

Battle

During the North Koreans' September 1 offensive, the US 25th Infantry Division's US 35th Infantry Regiment was heavily engaged in the Battle of Nam River north of Masan. On the 35th Regiment's right flank, just north of the confluence of the Nam River and the Naktong River, was the US 9th Infantry Regiment, US 2nd Infantry Division.[20] There, in the southernmost part of the 2nd Infantry Division zone, the 9th Infantry Regiment held a sector more than 20,000 yards (18,000 m) long, including the bulge area of the Naktong where the First Battle of Naktong Bulge had taken place earlier in August.[21] Each US infantry company on the river line here had a front of 3,000 feet (910 m) to 4,000 feet (1,200 m) and they held only key hills and observation points, as the units were extremely spread out along the wide front.[20]

During the last week of August, US troops on these hills could see minor North Korean activity across the river, which they thought was North Koreans organizing the high ground on the west side of the Naktong against a possible American attack.[22] There were occasional attacks on the 9th Infantry's forward positions, but to the men in the front lines this appeared to be only a standard patrol action.[20] On August 31, the UN forces were alerted to a pending attack when much of the Korean civilian labor force fled the front lines. Intelligence officers reported an attack was coming.[23]

On the west side of the Naktong, North Korean Major General Pak Kyo Sam, commanding the NK 9th Division, issued his operations order to the division on August 28. Its mission in the forthcoming attack was to outflank and destroy the US troops at Naktong Bulge by capturing the Miryang and Samnangjin areas to cut off the US 2nd Division's route of supply and withdrawal between Taegu and Pusan.[15] However, the North Koreans weren't aware that the US 2nd Infantry Division had recently replaced the US 24th Infantry Division in positions along the Naktong River. Consequently, they expected lighter resistance; the 24th troops were exhausted from months of fighting but the 2nd Division men were fresh and newly arrived in Korea.[20] They had only recently been moved into the line.[15][22] The North Koreans began crossing the Naktong River under cover of darkness at certain points.[23]

Battle of Agok

On the southern-most flank of the 9th Infantry river line, just above the junction of the Nam River with the Naktong, A Company of the 1st Battalion was dug in on a long finger ridge paralleling the Naktong that terminates in Hill 94 at the Kihang ferry site.[24] The river road from Namji-ri running west along the Naktong passes the southern tip of this ridge and crosses to the west side of the river at the ferry.[25] A small village called Agok lay at the base of Hill 94 and 300 yards (270 m) from the river.[24] A patrol of tanks and armored vehicles, together with two infantry squads of A Company, 9th Infantry, held a roadblock near the ferry and close to Agok.[25] On the evening of August 31, A Company moved from its ridge positions overlooking Agok and the river to new positions along the river below the ridge line.[24]

That evening Sergeant Ernest R. Kouma led the patrol of two M26 Pershing tanks and two M19 Gun Motor Carriages in Agok.[25] Kouma placed his patrol on the west side of Agok near the Kihang ferry. At 20:00 a heavy fog covered the river, and at 22:00 mortar shells began falling on the American-held side of the river.[26] By 22:15 this strike intensified and North Korean mortar preparation struck A Company's positions. American mortars and artillery began firing counterbattery.[23] Some of the A Company men reported they heard noises on the opposite side of the river and splashes in the water.[24]

At 22:30 the fog lifted and Kouma saw that a North Korean pontoon bridge was being laid across the river directly in front of his position.[24] Kouma's four vehicles attacked this structure, and after about a minute of heavy fire the bridge collapsed, and the ponton boats used to hold the bridge in place were sunk. At 23:00 a small arms fight flared around the left side of A Company north of the tanks.[25] This gunfire had lasted only two or three minutes when the A Company roadblock squads near the tanks received word by field telephone that the company was withdrawing to the original ridge positions and that they should do likewise.[24]

Kouma's patrol was then ambushed by a group of North Koreans dressed in US military uniforms.[27] Kouma was wounded and the other three vehicles had to withdraw, but he held the Agok site until 07:30 the next morning with his single tank.[25] In the attack against A Company, the North Koreans hit the 1st Platoon, which was near Agok, but they did not find the 2nd Platoon northward.[27]

The NK 9th Division's infantry crossing of the Naktong and attack on its east side near midnight quickly overran the positions of C Company, north of A Company.[26] There the North Koreans assaulted in force, signaled by green flares and blowing of whistles. The company held its positions only a short time and then attempted to escape.[21] Many of the men moved south, a few of them coming into A Company's ridge line positions near Agok during the night. Most of C Company moved all the way to the 25th Division positions south of the Naktong. On September 1 that division reported that 110 men of C Company had come into its lines.[27]

North Korean crossing

Meanwhile, 5 miles (8.0 km) north of Agok and A Company's position, B Company, 9th Infantry, held a similar position on Hill 209 overlooking the Paekchin ferry crossing of the river.[26] This ferry was located at the middle of the Naktong Bulge where the Yongsan road came down to the Naktong and crossed it.[28] The US 2nd Infantry Division had planned a reconnaissance mission to start from there the night of August 31, the same night that the NK I Corps offensive rolled across the river.[29]

Near the end of the month two reconnaissance patrols from the 9th Infantry had crossed to the west side of the Naktong and observed North Korean tank and troop activity 2 miles (3.2 km) west of the river.[26] Information obtained later indicated it was in fact the command post of the NK 9th Division.[28] On August 25, 9th Infantry commander Colonel John G. Hill outlined projected "Operation Manchu," which was to be a company-sized combat patrol to cross the river, advance to the suspected North Korean command post and communications center, destroy it, capture prisoners, and collect intelligence.[29]

The 9th Infantry Regiment had planned Task Force Manchu on orders from the 2nd Division commander Major General Laurence B. Keiser, which in turn had received instructions from Eighth United States Army commander Lieutenant General Walton Walker for aggressive patrolling.[29] Keiser decided the patrol should cross the river at the Paekchin ferry. The 9th Infantry reserve, E Company, reinforced with one section of light machine guns from H Company, was to be the attack force.[28] The 1st Platoon, 2nd Engineer Combat Battalion, was to transport it across the river in assault boats the night of August 31. Two heavy weapons companies, D and H, were each to furnish one section of heavy machine guns, one section of 81-mm. mortars, and one section of 75-mm. recoilless rifles for supporting fires. A platoon of 4.2-inch mortars was also to give support.[29]

After dark on August 31, First Lieutenant Charles I. Caldwell of D Company and First Lieutenant Edward Schmitt of H Company, 9th Infantry, moved their men and weapons to the base of Hill 209, which was within B Company's defense sector and overlooked the Paekchin ferry crossing of the Naktong River.[29] The raiding force, E Company, was still in its regimental reserve position about 2 miles (3.2 km) west of Yongsan, getting ready with the engineer platoon to move to the crossing site.[28] Colonel Hill went forward in the evening with the 4.2-inch mortar platoon to its position at the base of Hill 209 where the mortarmen prepared to set up their weapons.[30]

By 21:00, the closest front line unit was B Company on top of Hill 209, 1 mile (1.6 km) north of the river road which curved around the hill's southern base.[28] The regimental chaplain, Captain Lewis B. Sheen, had gone forward in the afternoon to B Company to hold services. On top of Hill 209, Chaplain Sheen and men in B Company after dark heard splashing in the water below them. They soon discovered a long line of North Korean soldiers wading the river.[30]

The first North Korean crossing at the Paekchin ferry caught the Heavy Mortar Platoon unprepared in the act of setting up its weapons.[28] It also caught most of the D and H Company men at the base of Hill 209, .5 miles (0.80 km) from the crossing site. The North Koreans killed or captured many of the troops there.[30] Hill was there, but escaped to the rear just before midnight, together with several others, when the division canceled Operation Manchu because of the attacks.[28] The first heavy weapons carrying party was on its way up the hill when the North Korean attack engulfed the men below. It hurried on to the top where the advance group waited and there all hastily dug in on a small perimeter. This group was not attacked during the night.[30]

From 21:30 until shortly after midnight the NK 9th Division crossed the Naktong at a number of places and climbed the hills quietly toward the 9th Infantry river line positions.[30] Then, when the artillery barrage preparation lifted, the North Korean infantry were in position to launch their assaults. These began in the northern part of the regimental sector and quickly spread southward.[28] At each crossing site the North Koreans would overwhelm local UN defenders before building pontoon bridges for their vehicles and armor.[30]

At 02:00, B Company was attacked.[26] A truck stopped at the bottom of the hill, a whistle sounded, then came a shouted order, and North Korean soldiers started climbing the slope.[31] The hills on both sides of B Company were already under attack as was also Hill 311, a rugged terrain feature a 1.5 miles (2.4 km) from the river and the North Koreans' principal immediate objective.[28] The North Koreans apparently were not aware of the Task Force Manchu group lower down on the hill and it was not attacked during the night. But higher up on Hill 209 the North Koreans drove B Company from its position, inflicting very heavy casualties on it. Sheen led one group of soldiers back to friendly lines on 4 September.[31]

At 03:00, 1 September, the 9th Infantry Regiment ordered its only reserve, E Company to move west along the Yongsan-Naktong River road and take a blocking position at the pass between Cloverleaf Hill and Obong-ni Ridge, 3 miles (4.8 km) from the river and 6 miles (9.7 km) from Yongsan.[31] This was the critical terrain where so much heavy fighting had taken place in the first battle of the Naktong Bulge.[28] Fighting began at the pass at 02:30 when an American medium tank of A Company, 72nd Tank Battalion, knocked out a T-34 at Tugok, also called Morisil. E Company never reached its blocking position.[31] A strong North Korean force surprised and delivered heavy automatic fire on it at 03:30 from positions astride the road east of the pass. The company suffered heavy casualties, including the company commander and Keiser's aide who had accompanied the force.[28] With the critical parts of Cloverleaf Hill and Obong-ni Ridge, the best defensive terrain between Yongsan and the river, the North Koreans controlled the high ground. The US 2nd Infantry Division now had to base its defense of Yongsan on relatively poor defensive terrain, the low hills at the western edge of the town.[31]

US 23rd Infantry attacked

North of the 9th Infantry sector of the 2nd Infantry Division front along the Naktong, the US 23rd Infantry Regiment on August 29 had just relieved the 3rd Battalion of the US 38th Infantry Regiment, which in turn had only a few days before relieved the US 21st Infantry Regiment of the US 24th Infantry Division.[26] On August 1, the 23rd Regiment was in a new sector of which it had only a limited knowledge.[32] It took over a 16,000 yards (15,000 m) Naktong River front without its 3rd Battalion which had been attached to the US 1st Cavalry Division to the north. Colonel Paul L. Freeman, the regimental commander, deployed the 1st Battalion on the high ground along the river with the three companies abreast.[31] The 1st Battalion, under US Lieutenant Colonel Claire E. Hutchin, Jr., outposted the hills with platoons and squads. He placed the 2nd Battalion in a reserve position 8 miles (13 km) behind the 1st Battalion and in a position where it commanded the road net in the regimental sector.[28] On August 31h the 2nd Division moved E Company south to a reserve position in the 9th Infantry sector.[33]

Two roads ran through the regimental sector from the Naktong River to Changnyong.[26] The main road bent south along the east bank of the river to Pugong-ni and then turned northeast to Changnyong. A northern secondary road curved around marshland and lakes, the largest of which was Lake U-p'o, to Changnyong. In effect, the 1st Battalion of the 23rd Regiment guarded these two approach routes to Changnyong.[33]

The 42 men of the 2nd Platoon, B Company, 23rd Infantry held outpost positions on seven hills covering a 2,600 yards (2,400 m) front along the east bank of the Naktong north of Pugong-ni.[33] Across the river in the rice paddies they could see, in the afternoon of August 31, two large groups of North Korean soldiers. Occasionally artillery fire dispersed them.[28] Just before dark, the platoon saw a column of North Koreans come out of the hills and proceed toward the river. They immediately reported to the battalion command post. The artillery forward observer, who estimated the column at 2,000 people, thought they were refugees. Freeman immediately ordered the artillery to fire on the column, reducing its number. However the North Koreans continued their advance.[33]

At 21:00 the first shells of what proved to be a two-hour North Korean artillery and mortar preparation against the American river positions of 2nd Platoon.[26] As the barrage rolled on, North Korean infantry crossed the river and climbed the hills in the darkness under cover of its fire.[28] At 23:00 the barrage lifted and the North Koreans attacked 2nd Platoon, forcing it from the hill after a short fight. Similar assaults took place elsewhere along the battalion outpost line.[33]

On the regimental left along the main Pugong-ni-Changnyong road North Korean soldiers completely overran C Company by 0300 September 1.[26] Only seven men of C Company could be accounted for, and three days later, after all the stragglers and those cut off behind North Korean lines had come in, there were only 20 men in the company.[28] As the North Korean attack developed during the night, 1st Battalion succeeded in withdrawing a large part of its force, less C Company, just north of Lake U-p'o and the hills there covering the northern road into Changnyong, 3 miles (4.8 km) east of the river and 5 miles (8.0 km) west of the town. B Company lost heavily in this action.[34]

When word of the disaster that had overtaken 1st Battalion reached regimental headquarters, Freeman obtained the release of G and F Companies from 2nd Division reserve and sent the former to help 1st Battalion and the latter on the southern road toward Pugong-ni and C Company. Major Lloyd K. Jenson, executive officer of the 2nd Battalion, accompanied F Company down the Pugong-ni road.[34] This force was unable to reach C Company, but Jenson collected stragglers from it and seized high ground astride this main approach to Changnyong near Ponch'o-ri above Lake Sanorho, and went into a defensive position there.[28] The US 2nd Division released E Company to the regiment and the next day it joined F Company to build up what became the main defensive position of the 23d Regiment in front of Changnyong.[34] North Korean troops during the night passed around the right flank of 1st Battalion's northern blocking position and reached the road three miles behind him near the division artillery positions.[28] The 23rd Infantry Headquarters and Service Companies and other miscellaneous regimental units finally stopped this penetration near the regimental command post 5 miles (8.0 km) northwest of Changnyong.[34]

US 2nd Division split

Before the morning of 1 September had passed, reports coming in to US 2nd Division headquarters made it clear that North Koreans had penetrated to the north-south Changnyong-Yongsan road and cut the division in two;[28] the 38th and 23d Infantry Regiments with the bulk of the division artillery in the north were separated from the division headquarters and the 9th Infantry Regiment in the south.[26] Keiser decided that this situation made it advisable to control and direct the divided division as two special forces.[35] Accordingly, he placed the division artillery commander, Brigadier General Loyal M. Haynes, in command of the northern group. Haynes' command post was 7 miles (11 km) north of Changnyong. Task Force Haynes became operational at 10:20, September 1. Southward, in the Yongsan area, Keiser placed Brigadier General Joseph S. Bradley, Assistant Division Commander, in charge of the 9th Infantry Regiment, the 2nd Engineer Combat Battalion, most of the 72nd Tank Battalion, and other miscellaneous units of the division. This southern grouping was known as Task Force Bradley.[34]

All three regiments of the NK 2nd Division-the 4th, 17th, and 6th, in line from north to south-crossed during the night to the east side of the Naktong River into the 23rd Regiment sector. The NK 2nd Division, concentrated in the Sinban-ni area west of the river, had, in effect, attacked straight east across the river and was trying to seize the two avenues of advance into Changnyong above and below Lake U-p'o. On August 31, 1950, Lake U-p'o was a large body of water although in most places very shallow.[36]

At dawn September 1, Keiser at 2nd Division headquarters in Muan-ni, 7 miles (11 km) east of Yongsan on the Miryang road, felt his division was in the midst of a crisis.[36] The massive North Korean attack had made deep penetrations everywhere in the division sector except in the north in the zone of the 38th Infantry.[35] The NK 9th Division had effected major crossings of the Naktong at two principal points against the US 9th Infantry; the NK 2nd Division in the meantime had made three major crossings against the US 23rd Infantry; and the NK 10th Division had begun crossing more troops in the Hill 409 area near Hyongp'ung in the US 38th Infantry sector. At 08:10 Keiser telephoned Eighth Army headquarters and reported the heaviest and deepest North Korean penetrations were in the 9th Infantry sector.[36]

Liaison planes rose from the division strip every hour to observe the North Korean progress and to locate US 2nd Infantry Division front-line units.[37] Communication from division and regimental headquarters to nearly all the forward units was broken.[35] Beginning at 09:30 and continuing throughout the rest of the day, the light aviation section of the division artillery located front-line units cut off by the North Koreans, and made fourteen airdrops of ammunition, food, water, and medical supplies.[37] As information slowly built up at division headquarters it became apparent that the North Koreans had punched a hole 6 miles (9.7 km) wide and 8 miles (13 km) deep in the middle of the division line and made less severe penetrations elsewhere.[26] The front-line battalions of the US 9th and 23rd Regiments were in various states of disorganization and some companies had virtually disappeared.[35] Keiser hoped he could organize a defense along the Changnyong-Yongsan road east of the Naktong River, and prevent North Korean access to the passes eastward leading to Miryang and Ch'ongdo.[37]

Reinforcements

At 09:00 Walker requested the US Air Force to make a maximum effort along the Naktong River from Toksong-dong, just above the US 2nd Division boundary, southward and to a depth of 15 miles (24 km) west of the river.[35] He wanted the Air Force to isolate the battlefield and prevent further North Korean reinforcements and supplies from moving across the river in support of the North Korean spearhead units.[37] The Far East Command requested the US Navy to join in the air effort, and the US Seventh Fleet turned back from its strikes in the Inch'on-Seoul area and sped southward at full steam toward the southern battle front.[35] Walker came to the US 2nd Division front at 12:00 and ordered the division to hold at all costs. He had already ordered ground reinforcements to the Yongsan area.[37]

During the morning of 1 September, Walker weighed the news coming in from his southern front, wavering in a decision as to which part of the front most needed his Pusan Perimeter reserves.[37] Since midnight the NK I Corps had broken his Pusan Perimeter in two places-the NK 2nd and 9th Divisions in the US 2nd Division sector, and the NK 7th Division and NK 6th Division in the US 25th Division sector, below the junction of the Nam and Naktong Rivers.[35] In the US 2nd Division sector North Korean troops were at the edge of Yongsan, the gateway to the corridor leading 12 miles (19 km) eastward to Miryang and the main Pusan-Mukden railroad and highway.[37]

Eighth Army had in reserve three understrength infantry regiments and the 2-battalion British 27th Infantry Brigade which was not yet completely equipped and ready to be placed in line: The 1st Provisional Marine Brigade at Changwon, 6 miles (9.7 km) northeast of Masan, preparing for movement to the port of Pusan; the US 27th Infantry Regiment of the 25th Division which had arrived at Masan only the night before at 20:30 to relieve the 5th Regimental Combat Team, which was then to join the 24th Division in the Taegu area; and the US 19th Infantry Regiment of the US 24th Infantry Division, then with that division's headquarters at Kyongsan southeast of Taegu.[38] Walker alerted both the 24th Division headquarters, together with its 19th Regiment, and the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade to move at a moment's notice;[39] the 24th Division either to the 2nd or 25th Division fronts, and the marines to an unannounced destination.[40]

As the morning passed, General Walker decided that the situation was most critical in the Naktong Bulge area of the US 2nd Division sector.[38] There the North Koreans threatened Miryang and with it the entire Eighth Army position. At 11:00 Walker ordered US Marine Corps Brigadier General Edward A. Craig, commanding the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade, to prepare the marines to move at once.[39] The marines made ready to depart for the Naktong Bulge at 13:30.[40]

North Korean advance

The situation on the front was chaotic during the day September 1. The North Koreans at one place had crossed at the Kihang ferry, captured Agok, and scattered A Company, 9th Infantry at its positions from Agok northward. A Company withdrew to positions on the ridge line back of the river. From there at daylight the men could see North Korean soldiers on many of the ridges surrounding them, most of them moving east. After several hours, 2nd Platoon of A Company sent a patrol down the hill to Agok to obtain supplies abandoned there during the night, returning later with much needed water, rations, and ammunition.[41]

Later in the morning North Korean barges crossed the Naktong below A Company. The company sent a squad with a light machine gun to the southern tip of the ridge overlooking Agok to take these troops under fire. When the squad reached the tip of the ridge they saw that a North Korean force occupied houses at its base. The company hit these houses with artillery. The North Koreans broke from the houses, running for the river. At this the light machine gun at the tip of the ridge took them under fire, as did another across the Naktong to the south in the US 25th Infantry Division sector. Proximity fuze artillery fire decimated this group. Combined fire from all weapons inflicted an estimated 300 casualties on this North Korean force.[41] In the afternoon, US aircraft dropped food and ammunition to the company; only part of it was recovered. The 1st Battalion ordered A Company to withdraw the company that night.[42]

During the withdraw, however, A Company ran into a sizable North Korean force and had scattered in the ensuing fight. Most of the company, including its commander were killed at close range. In this desperate action, Private First Class Luther H. Story, a weapons squad leader, fought so tenaciously that he was awarded the Medal of Honor. Badly wounded, Story refused to be a burden to those who might escape, and when last seen was still engaging North Korean at close range. Of those in the company, approximately ten men escaped to friendly lines.[42] The next morning, under heavy fog, the group made its way by compass toward Yongsan. From a hill at 12:00, after the fog had lifted, the men looked down on the Battle of Yongsan which was then in progress.[43] That afternoon 20 survivors of the company merged into the lines of the 72nd Tank Battalion near Yongsan.[42] Stragglers from this position continued to stream in the next few days as well.[44]

The end of Task Force Manchu

In the meantime, Task Force Manchu was still holding its position along the Naktong River, about 5 miles (8.0 km) north of where A Company had been destroyed on the southern end of the line.[44] The perimeter position taken by the men of D and H Companies, 9th Infantry, who had started up the hill before the North Koreans struck, was on a southern knob of Hill 209, 0.5 miles (0.80 km) south of B Company's higher position.[32] In addition to the D and H Company men, there were a few from the Heavy Mortar Platoon and one or two from B Company. Altogether, 60 to 70 men were in the group. The group had an SCR-300 radio, a heavy machine gun, two light machine gun, a M1918 Browning Automatic Rifle, about 20 M1 Garand rifles, and about 40 carbines or pistols. Schmitt assumed command of the group.[44]

During the night Schmitt established radio communication with the 1st Battalion, 9th infantry.[44] When daylight came Schmitt and his group saw that they were surrounded by North Koreans. One force occupied the higher knob half a mile above them, formerly held by B Company. Below them, North Koreans continued crossing the river and moving supplies forward to their combat units, some of them already several miles eastward.[32] The North Koreans quickly discovered Task Force Manchu group. They first attacked it at 14:00 that afternoon, and were repulsed.[44] That night an estimated company attacked three times, pressing the fight to close quarters, but failed each time to penetrate the tight US perimeter.[32] Daylight of the second day disclosed many North Korean dead on the steep slopes outside the perimeter.[44]

In the afternoon of September 2 Schmitt radioed 1st Battalion for an airdrop of supplies.[32] A US plane attempted the drop, but the perimeter was so small and the slopes so steep that virtually all the supplies went into North Korean hands. The men in the perimeter did, however, recover from a drop made later at 19:00 some supplies and ammunition. Private First Class Joseph R. Ouellette, of H Company, left the perimeter to gather weapons, ammunition, and grenades from the North Korean dead. On several occasions he was attacked, and on one such occasion a North Korean soldier suddenly attacked Ouellette, who killed the North Korean in hand-to-hand combat.[45]

That same afternoon, the North Koreans sent an American prisoner up the hill to Schmitt with the message, "You have one hour to surrender or be blown to pieces."[32] Failing in frontal infantry attack to reduce the little defending force, the North Koreans now meant to take it under mortar fire.[45] Only 45 minutes later North Korean antitank fire came in on the knob and two machine guns from positions northward and higher on the slope of Hill 209 swept the perimeter. Soon, mortars emplaced on a neighboring high finger ridge eastward registered on Schmitt's perimeter and continued firing until dark.[46] The machine gun fire forced every man to stay in his foxhole. The lifting of the mortar fire after dark was the signal for renewed North Korean infantry attacks, all of which were repulsed.[32] But the number of killed and wounded within the perimeter was growing, and supplies were diminishing. There were no medical supplies except those carried by one aid man.[46]

The third day, September 3, the situation worsened. The weather was hot and ammunition, food and supplies were nearly completely exhausted. Since the previous afternoon, North Korean mortar barrages had alternated with infantry assaults against the perimeter.[47] Survivors later estimated there were about twenty separate infantry attacks repulsed. Two North Korean machine guns still swept the perimeter whenever anyone showed himself. Dead and dying US troops were in almost every foxhole.[46] Mortar fragments destroyed the radio and this ended all communication with other US units. Artillery fire and air strikes requested by Schmitt never came.[32] Some North Koreans worked their way close to the perimeter and threw grenades into it. Six times Ouellette leaped from his foxhole to escape grenades thrown into it. In this close action Ouellette was killed. Most of the foxholes of the perimeter received one or more direct mortar hits in the course of the continuing mortar fire.[47] One of these killed Schmitt on September 3. The command passed now to First Lieutenant Raymond J. McDoniel of D Company, senior surviving officer.[46]

At daylight on the morning of 4 September only two officers and approximately half the men who had assembled on the hill, were alive.[47] As the day passed, with ammunition down to about one clip per man and only a few grenades left and no help in sight, McDoniel decided to abandon the position that night.[46] When it got dark the survivors would split into small groups and try to get back to friendly lines.[47] That evening after dark the North Koreans launched another weak attack against the position.[46] At 22:00, McDoniel and Caldwell and 27 enlisted men slipped off the hill in groups of four. Master Sergeant Travis E. Watkins, still alive in his paralyzed condition, refused efforts of evacuation, saying that he did not want to be a burden to those who had a chance to get away.[32] He asked only that his carbine be loaded and placed on his chest with the muzzle under his chin. Like Oullette, he would also win the Medal of Honor for his actions. Of the 29 men who came off the hill the night of September 4, 22 escaped to friendly lines, many of them following the Naktong downstream, hiding by day and traveling by night, until they reached the lines of the US 25th Infantry Division.[48][49]

Members of Task Force Manchu who escaped from Hill 209 brought back considerable intelligence information of North Korean activity in the vicinity of the Paekchin ferry crossing site. At the ferry site the North Koreans had put in an underwater bridge. A short distance downstream, each night they placed a pontoon bridge across the river and took it up before dawn the next morning. Carrying parties of 50 civilians guarded by four North Korean soldiers crossed the river continuously at night, an estimated total of 800-1,000 carriers being used at this crossing site.[48]

Changyong

North of the US 9th Infantry and the battles in the Naktong Bulge and around Yongsan, the US 23d Infantry Regiment after daylight of September 1 was in a very precarious position.[38] Its 1st Battalion had been driven from the river positions and isolated 3 miles (4.8 km) westward. Approximately 400 North Koreans now overran the regimental command post, compelling Freeman to withdraw it about 600 yards (550 m).[50] There, 5 miles (8.0 km) northwest of Changnyong, the US 23rd Infantry Headquarters and Headquarters Company, miscellaneous regimental units, and regimental staff officers checked the North Koreans in a 3-hour fight.[51]

The North Koreans advanced to Changnyong itself during the afternoon of September 2, and ROK National Police withdrew from the town.[50] North Koreans were in Changnyong that evening. With his communications broken southward to the 2nd Infantry Division headquarters and the 9th Infantry, Haynes during the day decided to send a tank patrol down the Yongsan road in an effort to re-establish communication. C Company, 72nd Tank Battalion, led its tanks southward. They had to fight their way down the road through several roadblocks. Of the three tanks that started, only the lead tank got through to Yongsan. There, it delivered an overlay of Task Force Haynes' positions to Bradley.[51]

Still farther northward in the zone of the US 38th Infantry the North Koreans were also active. After the North Korean breakthrough during the night of August 31, Keiser had ordered the 2nd Battalion, 38th Infantry, to move south and help the 23rd Infantry establish a defensive position west of Changnyong.[50] In attempting to do this, the battalion found North Korean troops already on the ridges along the road. They had penetrated to Hill 284 overlooking the 38th Infantry command post. This hill and Hill 209 dominated the rear areas of the regiment. At 06:00 September 3, 300 North Koreans launched an attack from Hill 284 against the 38th Regiment command post. The regimental commander organized a defensive perimeter and requested a bombing strike which was denied him because the enemy target and his defense perimeter were too close to each other. But the Air Force did deliver rocket and strafing strikes.[52]

This fight continued until September 5. On that day F Company captured Hill 284 killing 150 North Koreans.[50] From the crest he and his men watched as many more North Koreans ran into a village below them. Directed artillery fire destroyed the village. Among the abandoned North Korean materiel on the hill, Schauer's men found twenty-five American BARs and submachine guns, a large American radio, thirty boxes of unopened American fragmentation and concussion grenades, and some American rations.[52]

1-23rd Infantry isolated

Meanwhile, during these actions in its rear, the 1st Battalion, 23rd Infantry, was cut off 3 miles (4.8 km) west of the nearest friendly units.[53] On September 1 the regiment ordered it to withdraw to the Changnyong area. At 14:00 a tank-infantry patrol was sent down the road, but it reported that an estimated North Korean battalion held the mountain pass just eastward of the battalion's defense perimeter. Upon receiving this report the battalion commander requested permission by radio to remain in his present position and try to obstruct the movement of North Korean reinforcements and supplies. That evening Freeman approved this request, and 1st Battalion spent three days in the isolated positions. During this time C-47 Skytrain planes supplied the battalion by airdrops.[52]

On the morning of September 1, 3rd Battalion, 38th Infantry moved in an attack westward from the 23rd Regiment command post near Mosan-ni to open the road to the 1st Battalion. On the second day of the fighting at the pass, the relief force broke through the roadblock with the help of air strikes and artillery and tank fire. The advanced elements of the battalion joined 1st Battalion at 17:00 September 2. That evening, North Koreans strongly attacked the 3rd Battalion, 38th Infantry, on Hill 209 north of the road and opposite 1st Battalion, driving one company from its position.[54]

On September 4, Haynes changed the boundary between the 38th and 23rd Infantry Regiments, giving the northern part of the 23rd's sector to the 38th Infantry, thus releasing 1st Battalion for movement southward to help the 2nd Battalion defend the southern approach to Changnyong.[54] The 1st Battalion, 23rd Infantry, about 1,100 men strong when the attack began, was now down to a strength of approximately 600 men. The 23rd Infantry now made plans to concentrate all its troops on the position held by its 2nd Battalion on the Pugong-ni-Changnyong road.[50] The 1st Battalion moved there and took a place on the left flank of the 2nd Battalion. At the same time the regimental command post moved to the rear of this position. In this regimental perimeter, the 23rd Infantry fought a series of hard battles. Simultaneously it had to send combat patrols to its rear to clear infiltrating North Koreans from Changnyong and from its supply road.[54]

Battle of Yongsan

On the morning of September 1 the 1st and 2nd Regiments of the NK 9th Division, in their first offensive of the war, stood only a few miles short of Yongsan after a successful river crossing and penetration of the American line.[55][56] The 3rd Regiment had been left at Inch'on, but division commander Major General Pak Kyo Sam felt the chances of capturing Yongsan were strong.[48]

On the morning of September 1, with only the shattered remnants of E Company at hand, the US 9th Infantry Regiment, US 2nd Infantry Division had virtually no troops to defend Yongsan.[55] Keiser in this emergency attached the 2nd Engineer Combat Battalion to the regiment. The US 72nd Tank Battalion and the 2nd Division Reconnaissance Company also were assigned positions close to Yongsan. The regimental commander planned to place the engineers on the chain of low hills that arched around Yongsan on the northwest.[57]

A Company, 2nd Engineer Combat Battalion, moved to the south side of the Yongsan-Naktong River road; D Company of the 2nd Engineer Battalion was on the north side of the road. Approximately 2 miles (3.2 km) west of Yongsan an estimated 300 North Korean troops engaged A Company in a fire fight.[58] M19 Gun Motor Carriages of the 82nd AAA Battalion supported the engineers in this action, which lasted several hours.[57] Meanwhile, with the approval of General Bradley, D Company moved to the hill immediately south of and overlooking Yongsan.[57] A platoon of infantry went into position behind it. A Company was now ordered to fall back to the southeast edge of Yongsan on the left flank of D Company. There, A Company went into position along the road; on its left was C Company of the Engineer battalion, and beyond C Company was the 2nd Division Reconnaissance Company. The hill occupied by D Company was in reality the western tip of a large mountain mass that lay southeast of the town.[57] The road to Miryang came south out of Yongsan, bent around the western tip of this mountain, and then ran eastward along its southern base.[55] In its position, D Company not only commanded the town but also its exit, the road to Miryang.[35][57]

North Koreans had also approached Yongsan from the south.[59] The US 2nd Division Reconnaissance Company and tanks of the 72nd Tank Battalion opposed them in a sharp fight.[57] In this action, Sergeant First Class Charles W. Turner of the Reconnaissance Company particularly distinguished himself. He mounted a tank, operated its exposed turret machine gun, and directed tank fire which reportedly destroyed seven North Korean machine guns. Turner and this tank came under heavy North Korean fire which shot away the tank's periscope and antennae and scored more than 50 hits on it. Turner, although wounded, remained on the tank until he was killed. That night North Korean soldiers crossed the low ground around Yongsan and entered the town from the south.[26][60]

At 09:35 September 2, while the North Koreans were attempting to destroy the engineer troops at the southern edge of Yongsan and clear the road to Miryang,[38] Walker spoke by telephone with Major General Doyle O. Hickey, Deputy Chief of Staff, Far East Command in Tokyo.[61] He described the situation around the Perimeter and said the most serious threat was along the boundary between the US 2nd and US 25th Infantry Divisions.[62] He described the location of his reserve forces and his plans for using them. He said he had started the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade toward Yongsan but had not yet released them for commitment there and he wanted to be sure that General of the Army Douglas MacArthur approved his use of them, since he knew that this would interfere with other plans of the Far East Command.[63] Walker said he did not think he could restore the 2nd Division lines without using them. Hickey replied that MacArthur had the day before approved the use of the US Marines if and when Walker considered it necessary.[61] A few hours after this conversation Walker, at 13:15, attached the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade to the US 2nd Division[39] and ordered a co-ordinated attack by all available elements of the division and the marines, with the mission of destroying the North Koreans east of the Naktong River in the 2nd Division sector and of restoring the river line.[38][62] The marines were to be released from 2nd Division control as soon as this mission was accomplished.[61][64]

A decision was reached that the marines would attack west at 08:00 on September 3 astride the Yongsan-Naktong River road;[65] the 9th Infantry, B Company of the 72nd Tank Battalion, and D Battery of the 82d AAA Battalion would attack northwest above the marines and attempt to re-establish contact with the US 23rd Infantry;[47] the 2nd Engineer Combat Battalion, remnants of the 1st Battalion, 9th Infantry, and elements of the 72nd Tank Battalion would attack on the left flank, or south, of the marines to reestablish contact with the 25th Division.[66] Eighth Army now ordered the US 24th Infantry Division headquarters and the US 19th Infantry Regiment to move to the Susan-ni area, 8 miles (13 km) south of Miryang and 15 miles (24 km) east of the confluence of the Nam River and the Naktong River. There it was to prepare to enter the battle in either the 2nd or 25th Division zone.[61]

The American counteroffensive of September 3–5 west of Yongsan, according to prisoner statements, resulted in one of the bloodiest debacles of the war for a North Korean division. Even though remnants of the NK 9th Division, supported by the low strength NK 4th Division, still held Obong-ni Ridge, Cloverleaf Hill, and the intervening ground back to the Naktong on September 6, the division's offensive strength had been spent at the end of the American counterattack.[53] The NK 9th and 4th divisions were not able to resume the offensive.[67]

NK 2nd Division destroyed

The NK 2nd Division made a new effort against the 23rd Infantry's perimeter in the predawn hours of September 8, in an attempt to break through eastward. This attack, launched at 02:30 and heavily supported with artillery, penetrated F Company. It was apparent that unless F Company's position could be restored the entire regimental front would collapse. When all its officers became casualties, First Lieutenant Ralph R. Robinson, adjutant of the 2nd Battalion, assumed command of the company.[54] With North Koreans rapidly infiltrating his company's position and gaining its rear, Robinson in the darkness made his way through them 500 yards (460 m) to A Company's position. There he obtained that company's reserve platoon and brought it back to F Company. He accomplished the dangerous and difficult task of maneuvering it into the gap in F Company's lines in darkness and heavy rain.[54]

The attack tapered off with the coming of daylight, but that night it resumed. The North Koreans struck repeatedly at the defense line. This time they continued the fighting into the daylight hours of 9 September.[54] The Air Force then concentrated strong air support over the regimental perimeter to aid the ground troops.[50] Casualties came to the aid stations from the infantry companies in an almost steady stream during the morning. All available men from Headquarters Company and special units were formed into squads and put into the fight at the most critical points. At one time, the regimental reserve was down to six men. When the attack finally ceased shortly after 12:00 the 23rd Regiment had an estimated combat efficiency of only 38 percent.[68]

This heavy night and day battle cost the NK 2nd Division most of its remaining offensive strength.[50] The medical officer of the NK 17th Regiment, 2nd Division, captured a few days later, said that the division evacuated about 300 men nightly to a hospital in Pugong-ni, and that in the first two weeks of September the 2nd Division lost 1,300 killed and 2,500 wounded in the fighting west of Changnyong. Even though its offensive strength was largely spent by September 9, the division continued to harass rear areas around Changnyong with infiltrating groups as large as companies. Patrols daily had to open the main supply road and clear the town.[68]

North Korean and US troops remained locked in combat along the Naktong River for several more days. The North Koreans' offensive capability was largely destroyed, and the US troops resolved to hold their lines barring further attack.[68]

North Korean withdrawal

The UN counterattack at Inchon collapsed the North Korean line and cut off all their main supply and reinforcement routes.[69][70] On September 19 the UN discovered the North Koreans had abandoned much of the Pusan Perimeter during the night, and the UN units began advancing out of their defensive positions and occupying them.[71][72] Most of the North Korean units began conducting delaying actions attempting to get as much of their army as possible into North Korea.[73] The North Koreans withdrew from the Masan area first, the night of September 18–19. After the forces there, the remainder of the North Korean armies withdrew rapidly to the North.[73] The US units rapidly pursued them north, passing over the Naktong River positions, which were no longer of strategic importance.[74]

Aftermath

The North Korean 2nd and 9th Divisions were almost completely destroyed in the battles. The 9th Division had numbered 9,350 men at the beginning of the offensive on September 1. The 2nd Division numbered 6,000.[18] Only a few hundred from each division returned to North Korea after the fight. The majority of the North Korean troops had been killed, captured or deserted.[75] All of NK II Corps was in a similar state, and the North Korean army, exhausted at Pusan Perimeter and cut off after Inchon, was on the brink of defeat.[76]

By this time, the US 2nd Infantry Division suffered 1,120 killed, 2,563 wounded, 67 captured and 69 missing during its time at Pusan Perimeter.[77] This included about 180 casualties it suffered during the First Battle of Naktong Bulge the previous month.[78] American forces were continually repulsed but able to prevent the North Koreans from breaking the Pusan Perimeter.[79] The division had numbered 17,498 on September 1, but was in excellent position to attack despite its casualties.[80] The 1st Provisional Marine Brigade suffered 185 killed and around 500 wounded during the Battle of Pusan Perimeter, most of which probably occurred at Yongsan.[78]

Of all the North Korean attacks along the Pusan Perimeter, the Second Battle of Naktong Bulge is seen by historians as the most serious threat. It was the battle in which the North Koreans made the most substantial gains, splitting the US 2nd Infantry Division in half and briefly capturing Yongsan, where they were very close to breaching through to the US forces' supply lines and threatening other divisions' rear areas.[62] However, once again the fatal weakness of the North Korean Army had cost it victory after an impressive initial success—its communications and supply were not capable of exploiting a breakthrough and of supporting a continuing attack in the face of massive air, armor, and artillery fire that could be concentrated against its troops at critical points.[51][81] By September 8, the North Korean attacks in the area had been repulsed.[63]

References

Citations

- ↑ Appleman 1998, p. 392

- ↑ Varhola 2004, p. 6

- ↑ Fehrenbach 2001, p. 138

- 1 2 Appleman 1998, p. 393

- ↑ Appleman 1998, p. 367

- ↑ Bowers, Hammong & MacGarrigle 2005, p. 149

- ↑ Appleman 1998, p. 369

- ↑ Fehrenbach 2001, p. 130

- ↑ Alexander 2003, p. 139

- ↑ Appleman 1998, p. 353

- ↑ Alexander 2003, p. 143

- 1 2 Catchpole 2001, p. 31

- ↑ Fehrenbach 2001, p. 136

- ↑ Fehrenbach 2001, p. 135

- 1 2 3 4 Fehrenbach 2001, p. 139

- ↑ Millett 2000, p. 508

- ↑ Alexander 2003, p. 181

- 1 2 Appleman 1998, p. 395

- ↑ Appleman 1998, p. 396

- 1 2 3 4 Appleman 1998, p. 443

- 1 2 Fehrenbach 2001, p. 141

- 1 2 Alexander 2003, p. 182

- 1 2 3 Fehrenbach 2001, p. 140

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Appleman 1998, p. 444

- 1 2 3 4 5 Fehrenbach 2001, p. 142

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Alexander 2003, p. 183

- 1 2 3 Appleman 1998, p. 445

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Fehrenbach 2001, p. 143

- 1 2 3 4 5 Appleman 1998, p. 446

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Appleman 1998, p. 447

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Appleman 1998, p. 448

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Fehrenbach 2001, p. 144

- 1 2 3 4 5 Appleman 1998, p. 449

- 1 2 3 4 5 Appleman 1998, p. 450

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Fehrenbach 2001, p. 146

- 1 2 3 Appleman 1998, p. 451

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Appleman 1998, p. 452

- 1 2 3 4 5 Alexander 2003, p. 184

- 1 2 3 Fehrenbach 2001, p. 147

- 1 2 Appleman 1998, p. 453

- 1 2 Appleman 1998, p. 454

- 1 2 3 Appleman 1998, p. 455

- ↑ Fehrenbach 2001, p. 152

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Appleman 1998, p. 456

- 1 2 Appleman 1998, p. 457

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Appleman 1998, p. 458

- 1 2 3 4 5 Fehrenbach 2001, p. 150

- 1 2 3 Appleman 1998, p. 459

- ↑ Fehrenbach 2001, p. 153

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Fehrenbach 2001, p. 155

- 1 2 3 Appleman 1998, p. 466

- 1 2 3 Appleman 1998, p. 467

- 1 2 Fehrenbach 2001, p. 154

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Appleman 1998, p. 468

- 1 2 3 Millett 2000, p. 532

- ↑ Catchpole 2001, p. 33

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Appleman 1998, p. 460

- ↑ Fehrenbach 2001, p. 148

- ↑ Millett 2000, p. 533

- ↑ Appleman 1998, p. 461

- 1 2 3 4 Appleman 1998, p. 462

- 1 2 3 Millett 2000, p. 534

- 1 2 Catchpole 2001, p. 36

- ↑ Catchpole 2001, p. 35

- ↑ Alexander 2003, p. 185

- ↑ Millett 2000, p. 535

- ↑ Appleman 1998, p. 464

- 1 2 3 Appleman 1998, p. 469

- ↑ Appleman 1998, p. 568

- ↑ Fehrenbach 2001, p. 159

- ↑ Bowers, Hammong & MacGarrigle 2005, p. 179

- ↑ Alexander 2003, p. 187

- 1 2 Appleman 1998, p. 570

- ↑ Bowers, Hammong & MacGarrigle 2005, p. 180

- ↑ Appleman 1998, p. 603

- ↑ Appleman 1998, p. 604

- ↑ Ecker 2004, p. 16

- 1 2 Ecker 2004, p. 20

- ↑ Ecker 2004, p. 14

- ↑ Appleman 1998, p. 382

- ↑ Millett 2000, p. 537

Sources

- Alexander, Bevin (2003), Korea: The First War We Lost, Hippocrene Books, ISBN 978-0-7818-1019-7

- Appleman, Roy E. (1998), South to the Naktong, North to the Yalu: United States Army in the Korean War, Department of the Army, ISBN 978-0-16-001918-0

- Bowers, William T.; Hammong, William M.; MacGarrigle, George L. (2005), Black Soldier, White Army: The 24th Infantry Regiment in Korea, Honolulu, Hawaii: University Press of the Pacific, ISBN 978-1-4102-2467-5

- Catchpole, Brian (2001), The Korean War, Robinson Publishing, ISBN 978-1-84119-413-4

- Ecker, Richard E. (2004), Battles of the Korean War: A Chronology, with Unit-by-Unit United States Casualty Figures & Medal of Honor Citations, McFarland & Company, ISBN 978-0-7864-1980-7

- Fehrenbach, T.R. (2001), This Kind of War: The Classic Korean War History – Fiftieth Anniversary Edition, Potomac Books Inc., ISBN 978-1-57488-334-3

- Gugeler, Russell A. (2005), Combat Actions in Korea, University Press of the Pacific, ISBN 978-1-4102-2451-4

- Varhola, Michael J. (2000), Fire and Ice: The Korean War, 1950–1953, Da Capo Press, ISBN 978-1-882810-44-4

Coordinates: 35°29′36″N 128°44′56″E / 35.4933°N 128.7489°E